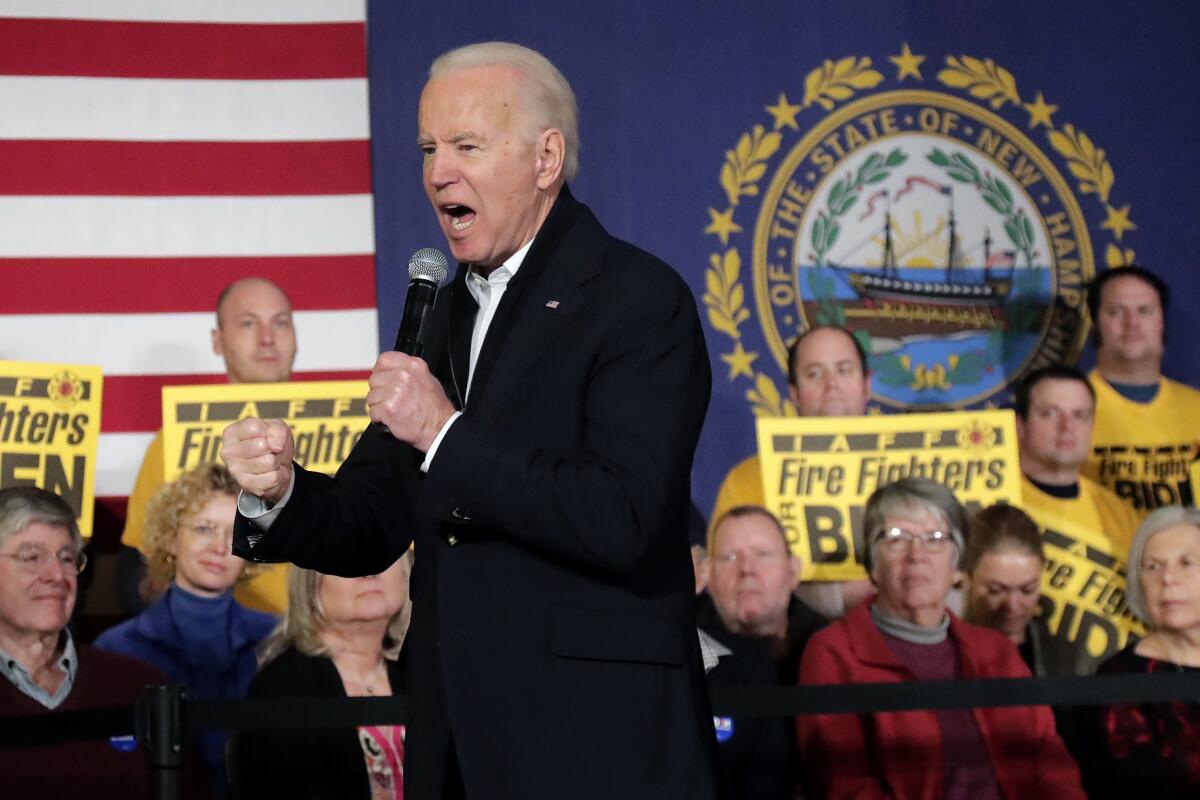

As some backers panic, Biden scrambles to save his campaign in New Hampshire

- Share via

SOMERSWORTH, N.H. — Joe Biden moved aggressively Wednesday to keep the walls from closing in further on his campaign in the aftermath of his dismal showing in Iowa, attacking his rivals in an effort to revive his candidacy before New Hampshire votes next week.

The former vice president was direct in his appeal as he sought to avoid back-to-back drubbings that many of his supporters fear could irreparably damage his presidential bid.

Gone were the talking points he and his aides had turned to initially in their attempt to downplay his fourth-place finish in Iowa.

“I’m not gonna sugarcoat it. We took a gut punch in Iowa,” Biden told a rally here. “The whole process took a gut punch. But look, this isn’t the first time in my life I’ve been knocked down.”

The former vice president attacked the two Iowa winners — Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Pete Buttigieg, former mayor of South Bend, Ind. — by name and in blunt terms. It was a dramatic change in tone, coming just a week after he warned Democrats in Iowa against forming a “circular firing squad” of negative campaigning.

“I have great respect for Mayor Pete and his service to this nation, but I do believe it’s a risk — to be just straight up with you for this part — to nominate somebody who’s never held an office higher than mayor of a town of 100,000 people in Indiana,” he said of Buttigieg.

As for Sanders, Biden said that if the Vermont senator were to win the nomination, Democrats “up and down the ballot … will have to carry the label that Sen. Sanders has chosen for himself. I don’t criticize him, he calls himself a democratic socialist.”

With more than 80% of the caucus results tallied in Iowa, Buttigieg and Sanders are running at the front of the pack, while Biden languishes in fourth place, behind the two leaders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Buttigieg poses a particular threat to Biden, as moderate voters and donors ponder the 38-year-old as a viable alternative to the septuagenarian former vice president.

As Biden stepped up his attacks on the stump, supporters scrambled to prop up his candidacy.

A super PAC working to elect Biden, called Unite the Country, announced it will spend $900,000 in New Hampshire over the next week to help him. The group is legally independent from Biden’s campaign but is run by former Biden aides.

Even with the infusion of money, the momentum Biden had when he entered the race will be extremely tough to reignite here.

Time is short, and Biden must raise money and prepare for Friday’s debate. Those conflicting needs were apparent Wednesday night when his campaign released his schedule for Thursday, showing no public events.

Sanders, the senator from neighboring Vermont, won the New Hampshire primary decisively in 2016 and again enjoys a significant lead in polls. And even though the delay in Iowa’s reporting of its results reduced its impact, Buttigieg bounded into the state with a boost from his success there. In the aftermath of the Iowa results, Buttigieg’s campaign had its best single hour of fundraising since its launch, spokesperson Lis Smith said.

Anxiety, by contrast, haunts Biden donors and fundraisers. The challenge of raising money for him has grown acute as supporters seek reassurance that he can win races. One Biden donor said it will be crucial for him to finish New Hampshire stronger than Buttigieg — a very high hurdle.

“He will need to show Bill-Clinton-comeback-kid momentum in New Hampshire,” said the donor, who asked not to be named discussing the campaign’s challenges.

If Biden falls short, the donor said, and the New Hampshire results look anything like those in Iowa, it could undercut fundraising and start to erode the “firewall” of support Biden‘s campaign argues he has built in more diverse states that vote later.

Among voters at Biden’s rallies, it’s not hard to find similar sentiments.

In Nashua on Tuesday, 56-year-old Lisa Milne expressed frustration that Biden’s advisors have not done enough to mitigate the damage since his campaign began to falter. Some of the problems Biden faces stem from the impeachment proceedings against President Trump, she said.

“This mess that the president got himself in, and he’s trying to drag Joe Biden into, I think has started to cast doubt,” she said. “So he’s got to figure out a clear message on how to articulate why none of that matters.”

She acknowledged other factors, however. “Joe’s clearly getting older, and it’s starting to show, and I think people are scratching their heads about his ability and his stamina,” Milne said.

In the past, Biden aides have often said that even if they lose in New Hampshire, his support in South Carolina, which votes Feb. 29, will serve as a firewall. That’s increasingly in doubt.

“It is one thing to come in second,” said Cornell Belcher, a pollster who worked on Barack Obama’s presidential campaign and has specialized in studying African American political opinion. “But coming in fourth and getting blown out in New Hampshire? History is not kind to candidates who that happens to.”

Black voters, who make up a majority of South Carolina’s Democratic electorate, have stayed with Biden so far, but their support is not guaranteed, Belcher warned.

“African American voters are fluid. They know and like Biden, but if it starts to look like he is not a good investment, they will move on.”

Bruce Ransom, a political scientist at Clemson University in South Carolina, similarly warned that any assumption by Biden’s campaign that its support is rock solid in the state is full of risk.

“If he doesn’t do well heading into South Carolina, he is in serious trouble,” Ransom said. “Voters here are looking for someone who can win.”

As Biden tries to stop the defection of supporters to Buttigieg and other moderates in the race, including Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, he is also at risk of losing voters to Sanders. Although the Vermont senator occupies the left of the field and Biden the center, the two compete for many of the same white, working-class voters.

Biden has attacked Sanders in the past, but now is taking him on more bluntly, particularly on Sanders’ support for Medicare for All.

“When Sanders attacks me for having baggage. I will tell you, the 60-plus candidates or so that campaign for the toughest districts in the country, just two years ago, don’t see me as baggage,” Biden said, pointing to the work he did to elect them. “They wanted me in their district.”

He also pushed back against Buttigieg’s portrayal of him as a creature of an old, failed Washington establishment, by citing his accomplishments as President Obama’s vice president.

“Is he really saying the Obama-Biden administration was a failure? Pete, just say it out loud,” Biden said, his voice rising.

Those arguments have swayed some voters. Jeff Stern, 46, a college professor from Portsmouth, came to Biden’s rally uncommitted on Wednesday and left leaning toward voting for him. But he was concerned Biden isn’t closing the deal with enough other voters.

“I do worry that Biden lacks the enthusiasm from people in New Hampshire,” Stern said after the event. “I left the rally feeling that I will likely vote for Joe, and hoping that he catches fire this week,” he added. “He needs it. “

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.