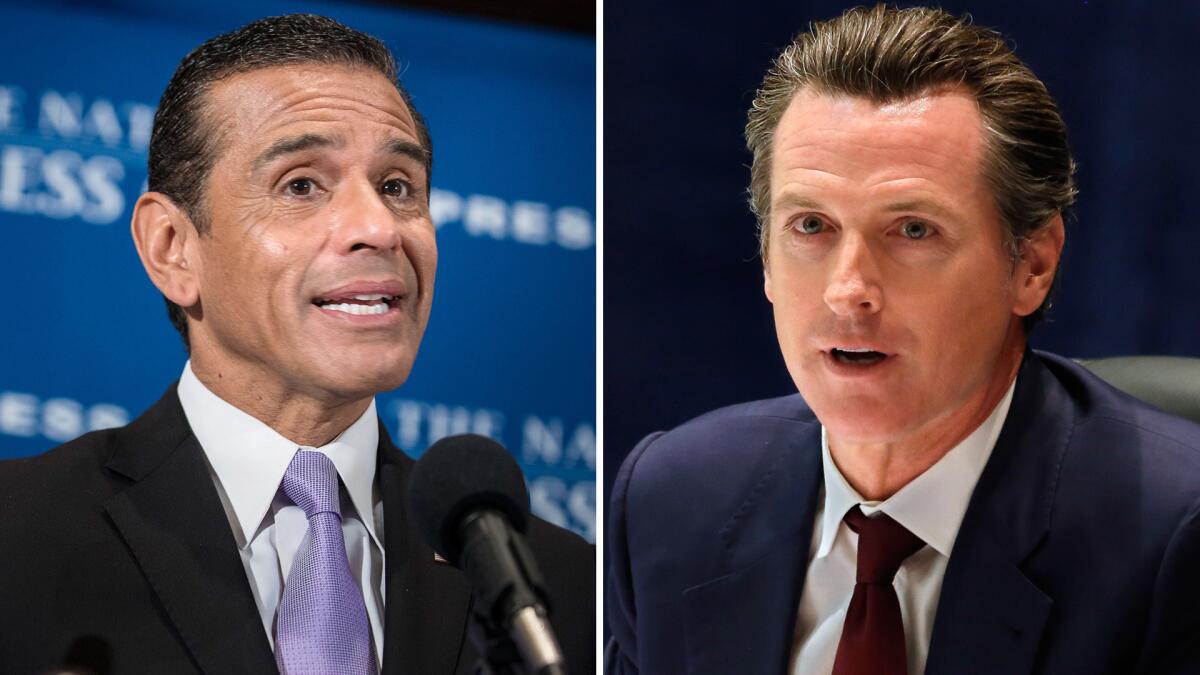

Villaraigosa and Newsom want to build more houses in California than ever before. Experts see the candidates’ goal as an empty promise

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Two of California’s leading candidates for governor say they’re going to end the housing shortage, a driver of the state’s affordability crisis.

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa both have said they want developers in California to build a half million homes in a year — something that’s never happened, at least in modern history. And they want builders to do it for seven straight years, resulting in 3.5 million new homes from the time the next governor takes office through 2025.

Those numbers are so out of scale with California’s history that they might be impossible to achieve. Practical concerns, including developers lining up enough financing and construction workers to build so many homes so quickly, could stymie the effort. Meeting the goals could also require rolling back decades of popular state policies on growth, taxation and the environment, according to housing academics and economists.

Without specific plans to transform how housing gets approved in California, said Christopher Thornberg, founding partner of Los Angeles-based consulting firm Beacon Economics, Newsom and Villaraigosa’s promises are empty.

“You’re just saying it,” Thornberg said of the homebuilding goals. “You don’t really mean it.”

Newsom and Villaraigosa said in separate statements to The Times that setting the 3.5-million home goal ensures they’ll be held accountable to whatever needs to be done to attain it.

Here’s why the two candidates’ goals will be so difficult to achieve and how they say they’re going to do it.

How many houses are we actually talking about?

For decades, not enough homes have been built in California to accommodate a growing population, leading to a spike in housing costs. Since 2011, for instance, the Bay Area has added about 627,000 new jobs but only 138,000 homes, according to the Building Industry Assn. of the Bay Area.

Newsom and Villaraigosa’s homebuilding goals would address that problem, but they’re without precedent.

Only twice since 1954 — the year the state building industry began tracking permits — have developers built more than 300,000 homes in a year. The highest year on record is 1963, when 322,018 home permits were issued.

To reach 500,000 homes in a year, the state would need to replicate its largest production in modern history plus an additional 178,000 homes, a number the state has surpassed just three times in the past 27 years.

Overall, the state’s rate of homebuilding would have to triple the historical average, quadruple last year’s production and reach nearly seven times the pace of building in the last decade.

Where do these numbers come from?

The goal of 3.5 million homes originated in a 2016 report on California’s housing problems by the McKinsey Global Institute, a private think tank.

The report found that California ranked 49th in the country in housing production per capita and estimated the state would need 3.5 million new units through 2025 to build homes at a per capita rate equivalent to New Jersey and New York.

California could achieve that goal, the report said, through a dramatic increase in development near transit, increasing building on parcels already zoned for apartments and condominiums and adding some units to single-family parcels.

But there’s a crucial difference between the McKinsey report and the pledges from Newsom and Villaraigosa. The McKinsey report sets a goal for California to build 3.5 million homes from 2015 through 2025, an 11-year period. The gubernatorial candidates want to do it in only seven years, a period that would begin when the new governor takes office in 2019.

How do they plan to get there?

Housing affordability has emerged as one of the most prominent issues in the gubernatorial campaign, and all major candidates have pledged to address the problem. State Treasurer John Chiang, also a Democrat, has set a goal of having developers build 1.6 million homes for low-income Californians by 2030 through a mix of state bond funding, tax credits and other subsidies.

Newsom and Villaraigosa, however, are the only ones to have set the 3.5-million home goal.

Newsom’s proposal relies on spending hundreds of millions of dollars more on low-income homes, approving some development through regional governments rather than solely at the local level and financially rewarding cities and counties that approve housing, especially near transit, and punishing those that don’t.

Villaraigosa emphasizes sequestering property tax dollars to finance low-income housing, making loans to homeowners who want to build a second unit on their lots and making unspecified changes to the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, the 1970 law that requires developers to analyze and lessen a project’s effect on the environment.

Neither of them, though, have specified how many homes they expect each part of their housing plans to produce to add up to 3.5 million homes. Instead, they contend that simply setting a bold goal will require them to allocate funding and reduce the red tape needed to meet it.

“A crisis of this magnitude requires ambitious goal setting matched with focused leadership and bold, innovative policy initiatives,” Newsom said in a statement responding to questions from The Times. “It requires an affordable housing ‘moonshot.’”

“Housing has to be delivered at the local level, and building consensus is the only way to get there,” Villaraigosa said in a statement. “It comes down to having the courage and experience to lead on this issue, and I am committed to getting it done.”

What would it actually take?

As governor, Newsom or Villaraigosa would have to reshape how housing gets permitted to make the process faster and more likely to result in approval.

Doing so, experts said, could require taking on three of the most substantial barriers to large-scale housing production, all of which have had long enjoyed broad support

Proposition 13, the 1978 ballot initiative that restricts property tax increases, which gives cities incentives to approve commercial and hotel development instead of housing because those projects generate more local tax revenues. It has also helped protect homeowners from rising taxes.

— The California Environmental Quality Act, which creates a lengthy process for assessing the effects of new housing and leaves projects vulnerable to litigation. Environmental groups also credit the law with preserving the state’s natural beauty.

— Local control over development decisions. Cities and counties determine what is built in their communities, and desirable coastal locales often prefer restrictions on growth. Los Angeles, for instance, had in 1960 zoned enough housing to accommodate 10 million people, a figure that’s since been reduced to a little over 4 million. Residents like to shape how their neighborhoods look.

Michael Lens, an associate professor of urban planning and public policy at UCLA, said the candidates would need to make substantial changes to all three policies, potentially even scrapping them, if they wanted to reach the homebuilding targets.

“You could take away one of those pillars and have a wobblier table of housing resistance,” Lens said. “But [removing] all three would be more useful.”

The housing production goal also could conflict with other promises. Newsom and Villaraigosa support California’s ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets, which require concentrating homes near jobs and transit so people drive less. That means the state couldn’t count on large, single-family developments, such as suburban projects built during an early 2000s surge in production, to meet the 3.5-million home target.

Even if it were politically possible to supercharge housing production, there are practical problems that the candidates would have less control over. After a long period of growth, Gov. Jerry Brown has warned that the state economy should expect a slowdown in the coming years, which could also decelerate development.

In addition, it takes time for builders to secure land and financing, no matter how quickly a government approves blueprints and permits. Changes implemented on the first day of a Newsom or Villaraigosa administration might take years before they’d lead to ribbon cuttings for new homes.

“Depending on the size of the project, the stuff that starts in 2019 might not even come online until somewhere around 2025,” Lens said.

There have to be enough construction workers to build all those homes, too. California contractors already are having trouble finding labor, and that’s before spending ramps up on more than $5 billion annually in road repairs and transit upgrades coming after the Legislature approved a gas tax hike last year, said Peter Tateishi, CEO of the Associated General Contractors of California.

“We don’t see a path to building 500,000 homes in one year on top of all the other infrastructure projects that are on the docket,” Tateishi said.

Twitter: @dillonliam

ALSO

California won’t meet its climate change goals without a lot more housing density in its cities

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.