How Villaraigosa lost the governor’s race despite tens of millions of dollars spent to boost his bid

- Share via

When Antonio Villaraigosa was elected mayor of Los Angeles, it signaled the growing clout of California’s Latino voters as well as the rise of a Democratic star whose charisma and ambition could take him to loftier perches.

More than a decade later, his long-stated dreams of leading the state ended Tuesday in a third-place primary finish despite $32 million spent by Villaraigosa’s campaign and outside groups on his behalf. Democratic rival Gavin Newsom badly beat the former L.A. mayor on his home turf, and Republican businessman John Cox trounced him for the second spot on the November ballot.

For the record:

6:45 p.m. June 6, 2018An earlier version of this story said that former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa appeared on the cover of a 2013 issue of Los Angeles magazine. He appeared on the cover of a 2009 issue of the magazine.

Some factors behind Villaraigosa’s defeat were out of his control. Republicans including President Trump rallied around a little-known GOP candidate in hopes that propelling a Republican to the top of the ticket would assist their party in its bid to hold on to Congress.

But some tactical decisions made by Villaraigosa’s campaign — he entered the race nearly two years after Newsom and spent little money to turn out the Latino voters crucial to his chances — may have narrowed his path to victory.

Eric Jaye, a top advisor to Villaraigosa, said he expected people to second-guess campaign strategy, but he believes it would have been difficult to overcome what appears to be dismal voter turnout.

“The reality is we didn’t have the resources that the front-runner did, and we had to do a lot more with less,” Jaye said. “We had to win L.A., we had to turn out the Latino vote and persuade working-class people that it did matter to vote for someone focused on high-wage jobs.”

It’s Newsom vs. Cox in November as Villaraigosa tumbles in governor’s race »

Villaraigosa launched his campaign two days after the November 2016 presidential contest. Traditionally, that would be enough of a runway to build a statewide bid, but Newsom kicked off his campaign nearly two years earlier. He led in the polls and fundraising throughout the race.

Newsom, the former mayor of San Francisco, stayed in the public eye as lieutenant governor while Villaraigosa left the mayor’s office in 2013 to work in the private sector.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who endorsed Newsom, said Villaraigosa leaving public life played a major role in his loss.

“He got in too late in comparison with Newsom, and the second related factor is he is not currently an officeholder, and he has not been an officeholder for several years, and those factors were pretty costly,” Ridley-Thomas said. “I think much of what he has done [since leaving office] was attending to personal matters, which are, after all, important … a new wife, a new home, a financial remuneration package. That’s mostly what we were hearing about.”

Fueled by unlimited donations, independent groups play their biggest role yet in a California primary for governor »

Newsom’s home base also worked to his advantage.

“Newsom is widely known in the Bay Area. Antonio is widely known in L.A.,” said Dan Newman, a senior advisor to Newsom. “Newsom is widely loved in the Bay Area, and Villaraigosa gets a ‘meh’ from the voters who know him best.”

Los Angeles County has more Democratic voters than the Bay Area, but Bay Area voters are more actively engaged and vote at a higher rate. Voters’ perceptions of Villaraigosa’s time in office could also have played a part in his primary tumble.

Elected in 2005, Villaraigosa was the first Latino elected mayor of Los Angeles in more than a century. Newsweek magazine featured him on its cover under the headline “Latino Power.”

Coverage of California politics »

But Villaraigosa steered the city during a recession that led to city employee layoffs, and the onetime union organizer fought with labor groups representing city workers and teachers.

And his reputation never fully recovered after the 2007 disclosure of his extramarital affair with a television reporter, which led to the public breakup of his marriage.

In 2009, he appeared on the cover of Los Angeles magazine with the headline “Failure” across his chest. When he left office four years later, Villaraigosa remained a polarizing figure in the city.

A USC Price/Los Angeles Times poll at the time showed his favorability ratings barely topped his negative ratings — although he was popular with younger voters and Latinos, he was significantly less so among whites and older voters.

Those factors enabled the Newsom campaign to lock down the Bay Area and spend significant resources building support in areas that were expected to favor Villaraigosa — Los Angeles and the Central Valley.

California’s major political parties feared the top-two primary but emerged as powerful as before »

The strategy worked: In Los Angeles County, Newsom received about 297,000 votes to Villaraigosa’s nearly 207,000, according to tallies through Wednesday afternoon by the California secretary of state’s office. In San Francisco County, Newsom received more than 86,000 votes to Villaraigosa’s more than 13,000.

Meanwhile, the Villaraigosa campaign spent much of its time focusing on Newsom.

One person close to the campaign, who asked for anonymity to speak freely about Villaraigosa’s defeat, said Newsom taking first place was a given, so the campaign should have focused on the candidates competing for second.

“There should have been more focus on John Cox, John Chiang and others trying to advance in the runoff,” the person said. “The strategy was overly focused on Gavin Newsom, when that should have been more of a general election strategy.”

The campaign was also caught flat-footed by Cox’s rise.

Holding on to several California congressional seats is key to the GOP’s efforts to retain control of Congress. Republican officials including House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield were worried that if no Republican advanced to the November election, GOP voter turnout would be depressed.

GOP leaders tried to recruit more prominent Republicans to run for governor, such as San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer. But they were unsuccessful, and later rallied around Cox.

Track the money that fueled the California primary for governor »

Then came the presidential tweet May 18, giving Cox an instant boost of 3 to 5 percentage points, according to internal polling from some campaigns. Cox’s campaign also had enough money for small but smartly targeted ad buys on Fox News and conservative talk radio.

The one-two punch of Trump’s Cox endorsement and a dismal turnout among Villaraigosa’s bases of voter support were insurmountable, said Mike Madrid, a Republican political consultant and senior advisor to the Villaraigosa campaign.

“From the day we began there were two main strategic concerns: the consolidation of the Republican vote. The second, we needed very strong Latino turnout. In the end, they both went against us,” Madrid said.

Multiple people in and around the campaign faulted it for not doing more to reach out to Latinos. The campaign spent $200,000 to $300,000 on Spanish-language advertising, while an independent expenditure group spent an additional half-million, according to multiple ad buyers. That’s less than what Newsom spent courting Latino voters.

Get-out-the-vote efforts also started too late.

“We started [the get-out-the-vote operation] one month out,” said the person close to the campaign. “It should have been at least the beginning of the year.”

Madrid disputed both of these notions, saying that even if the Latino vote was tripled, Villaraigosa still would not have placed second.

A campaign staffer who asked for anonymity wished that the major outside group supporting Villaraigosa, which spent $23 million, focused more on Latino voters.

The pro-charter schools group, Families and Teachers for Antonio Villaraigosa for Governor 2018, broke records in outside money spending on a gubernatorial primary in California. But the costly effort failed to make an impact.

A few rich charter school supporters are spending millions to elect Antonio Villaraigosa as California governor »

“It didn’t make any sense at all for the independent expenditure to spend its money going after Gavin Newsom. Newsom was going to make the runoff no matter what,” said Dan Schnur, a political communications professor at USC. “The open question is whether that effort could have been more help if it went after Cox instead, or mounted a strong outreach and turnout effort for Latino voters.”

Josh Pulliam, a spokesman for the charter schools group, said organizers went after Newsom to try to peel away more votes for Villaraigosa.

“If underdogs won half the time or more, they wouldn’t be underdogs,” he said. “[Villaraigosa] started in single digits in our polls. There just weren’t enough Democrats out there for him to capture.”

In the final weeks of the campaign, Villaraigosa knew that sliding into the top two would be difficult but didn’t lose hope. He’s always been counted out, and he always fought back, he often said on the campaign trail.

Prone to fistfights as a boy, he was kicked out of one high school and dropped out of another. He said his mother told him not to give up: “Sí, se puede. You can do it.”

Villaraigosa wound up receiving a bachelor’s degree at UCLA and a law degree from Peoples College of Law near MacArthur Park, but did not pass the bar exam.

He won an Assembly seat in 1994 after years working as a labor organizer and later became Assembly speaker.

In 2001, he ran for mayor of Los Angeles only to lose to James Hahn. But after spending time on the Los Angeles City Council, Villaraigosa ran again for mayor in 2005 and beat Hahn handily.

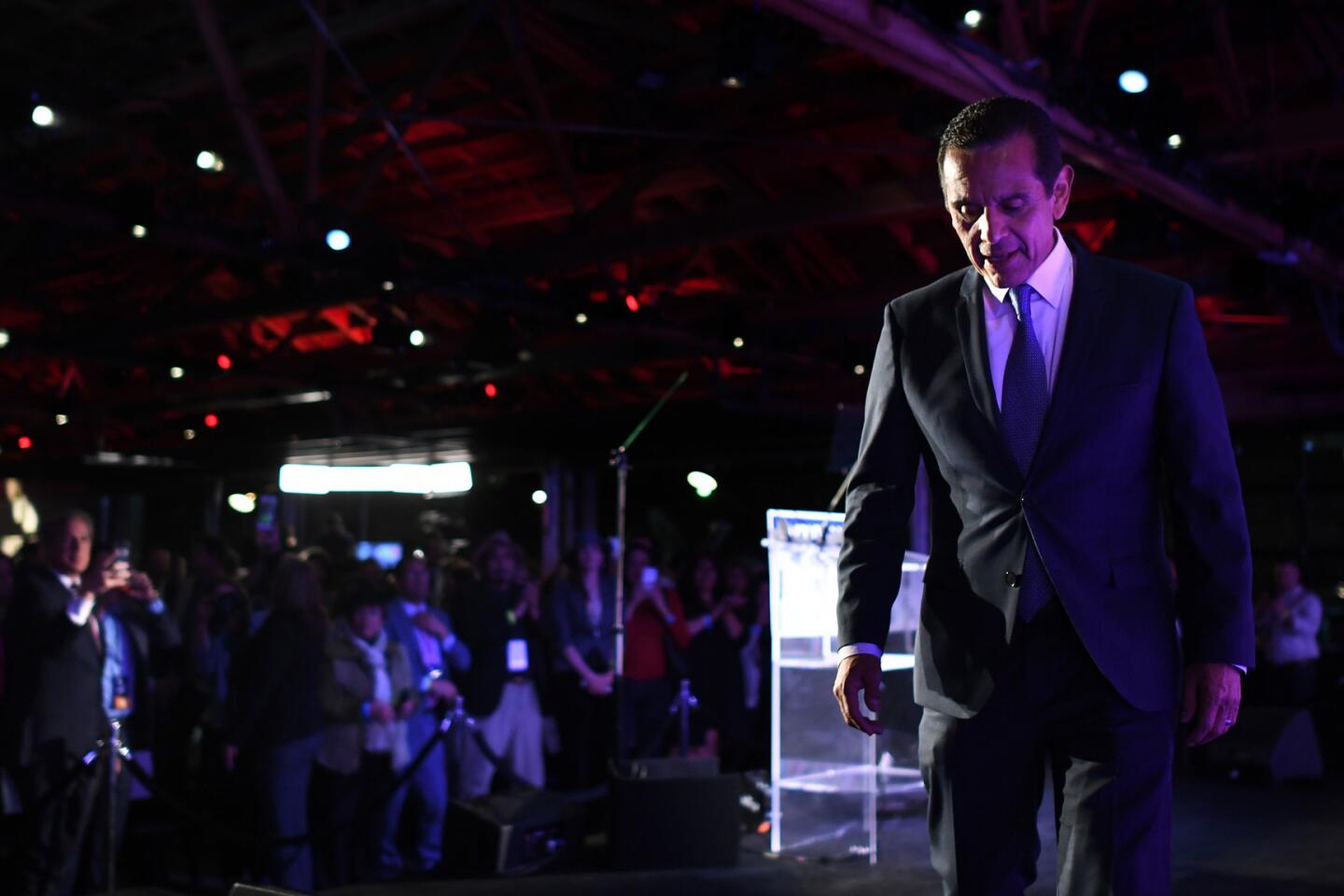

Villaraigosa didn’t speak publicly Wednesday about his loss. But the charm that powered his mayoral run was evident as he made a gracious concession speech Tuesday night.

“Thank you everybody, we’re done,” he said. “But you know what? Never, never miss an opportunity to celebrate life, love and family. So enjoy the evening.”

Times staff writers Melanie Mason, Jaclyn Cosgrove and Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

[email protected]; [email protected]

Twitter: @LATSeema; @philwillon

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.