Editorial: Stop minor traffic stops. They are an excuse to randomly search cars — and can turn deadly

- Share via

An enormous amount of police time and resources go into traffic patrol, in which officers pull over motorists for infractions as minor as a single nonfunctioning taillight. Traffic stops have become police surveillance tools, a pretext to search vehicles for guns, drugs or other goods that might be stolen, illicit or dangerous.

Court rulings interpreting the 4th Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures permit police to check a car for items that are within the driver’s reach, in order to assure their own safety during the stop. But the search often extends to areas well out of reach — the backseat, the trunk, under the hood — ostensibly based on the driver’s consent.

A standard tactic is for the officer who stopped the car to say, “Do me a favor and open the trunk.” The driver, having handed over a driver’s license and registration, is clearly not free to go and is unlikely to believe he or she has an option regarding the search. But the officer can testify in court that the search was consensual, because the driver was just doing the officer “a favor,” not complying with an order.

At a time of justified concern about arbitrary police stops, the Supreme Court on Monday made such harassment more likely rather than less.

The subjects of these kinds of police stops and searches are disproportionately people of color, especially Black drivers. The stops have become a major cause of resentment and mistrust of police in the Black community, and also a major factor in needless police violence when encounters escalate from routine to tense and sometimes fatal.

Police argue that it’s not their fault, they merely are going where the crime is. They say they more intensely police parts of town where drivers are more likely to be carrying dangerous contraband. On first blush, the argument sounds rational and the disproportionate impact on Black and Latino drivers merely an unhappy consequence of living in more dangerous neighborhoods that require a higher level of police response.

Automated speed enforcement has reduced crashes and deaths in the cities where it’s used. California lawmakers should let L.A. and other cities try speed cameras on the most dangerous streets.

A series of Times stories from 2019 undermines this excuse. Analyzing Los Angeles Police Department traffic stops, The Times found that even though Black and Latino drivers were searched more, contraband was disproportionately found not in their cars, but in cars driven by white motorists.

A later analysis by the Police Commission’s inspector general confirmed that the use of pretextual stops was a failed crime strategy. It also revealed that police failed to report many of their stops as required by California law. Video showed that police subjected Black and Latino motorists to harsher treatment: handcuffing them, forcing them to stand with their face against walls or lie down on the pavement, questioning them about their backgrounds and checking their tattoos. None of it helped lower the crime rate.

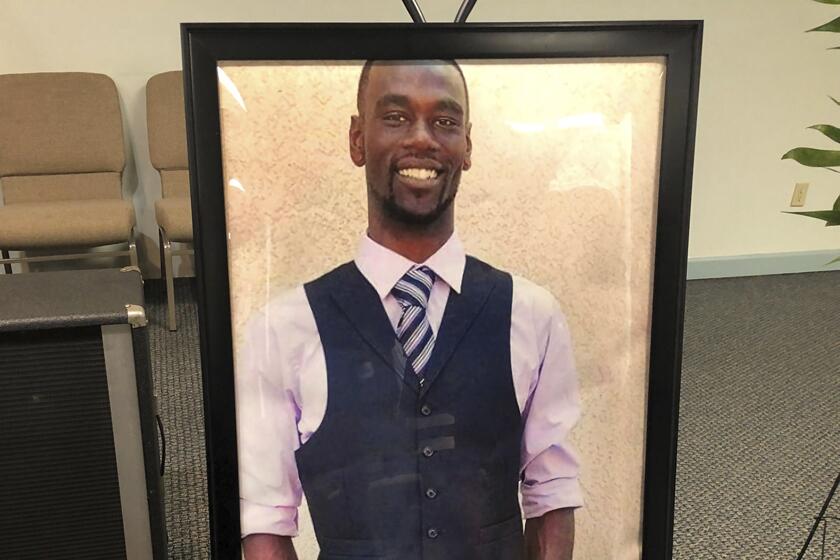

The Tyre Nichols beating video is being cited as evidence that race isn’t a factor in excessive police force, policing can’t be reformed, a few bad cops are ruining the profession, nothing has changed in law enforcement, and victims of police violence are to blame. But the video shows none of that.

A state report on annual police traffic stop data statewide showed similarly disproportionate stops by race. It also showed that the use of force on Black drivers was 2.2 times the rate with white drivers.

Los Angeles altered its traffic stop tactics in response to The Times stories, and meanwhile it and other cities have been studying how to drive down disparate, ineffective and demeaning police treatment of Black and Latino drivers.

Editorial: Lots of talk, still too little change to policing three years after George Floyd’s murder

The 2020 killing in Minneapolis ignited a summer of protest and debate about the role of police, but little constructive action. But there are some promising developments.

Those studies slog on, but California Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) has a bill this session that gets to the heart of the issue by eliminating minor police traffic stops for infractions — like misplaced license plate, expired registration tags or a single broken running light — that could easily be handled with a citation sent by mail, and without a stop or a search.

It’s the right move, and despite vigorous opposition by police unions, it would not erode street safety. There would remain approximately 1,000 lawful reasons, according to the bill’s backers, for police to cite drivers. Police would still be able to stop and cite motorists for reckless driving, drunk driving and unsafe driving. Two broken taillights? The officer could still pull over the car.

Similar bills have previously stalled under police union pressure, to the detriment of police-community relations, street safety and crime-fighting. It’s time to move this bill forward and end traffic stops as a pretext for police surveillance and racially disproportionate enforcement.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.