L.A. Metro cops are in a bind: Avoid racial profiling while also fighting crime

- Share via

The Chrysler sedan was parked illegally against a red curb on West Manchester Avenue shortly after nightfall when a man walked up to the front passenger window, then retreated.

To the two officers from the Los Angeles Police Department’s elite Metropolitan Division in an unmarked Crown Victoria, it looked like a possible drug deal.

They asked a black man in a Raiders hoodie and a black woman in a denim jacket to step out of the car. As the pair stood facing a metal fence, the officers patted them down.

After a Times investigation showing that Metro pulled over black drivers at a rate more than five times their share of the city’s population, Mayor Eric Garcetti in early February ordered the LAPD to scale back on vehicle stops like this one.

At Metro’s Temple Street headquarters, the Times article and mayor’s directive caused an uproar. Metro officers felt they were being maligned as racists for policing a part of the city where almost everyone is black or Latino.

On the ground with Metro in South L.A., the realities are more complex than statistics can capture, with decisions about which drivers to stop shaped by years of experience with possible crime indicators, from the man walking up to a parked car to the paper license plates sometimes used to hide a car’s origins.

As a mobile strike force responding to flare ups and tamping down gang wars, Metro remains a key player in the LAPD’s crime-reduction strategy.

Despite the mayor’s directive, much of the work of Metro’s crime suppression squads still revolves around pulling over motorists to root out criminal suspects, illegal guns and contraband.

But with a progressive mayor and perhaps the city’s most progressive police chief ever, the LAPD is under unprecedented pressure to pull back from tactics like vehicle stops and data policing that carry implications of racial bias.

As the city heads into the summer, a prime season for violence, this new way of policing will be tested. Homicides and shootings have already surged in the last month or so, claiming more than a dozen lives, including rap star Nipsey Hussle.

LAPD officials warn that if Metro withdraws from South L.A., as some community groups are demanding, lives will be lost.

“We’re trying to stop drive-by shootings,” said Capt. Jonathan Tippet, who leads Metro. “If we’re not here, it’s going to have a negative impact and allow people to go back to committing crime. If we’re not here to keep the peace, we’re going to have bloodshed.”

While filling out paperwork documenting the stop of the white Chrysler, the officers explained their actions to a Times reporter.

The parking violation and suspected narcotics transaction provided a legal reason to approach the car, said Amanda Lankford, one of the few female officers in Metro.

She and her partner, Julio Lopez, asked everyone in the car to step out because the back window was tinted, and it was unclear who was inside, Lankford said. The officers asked them for permission to pat them down because drug dealers are sometimes armed.

After finding nothing suspicious, they explained the reason for the stop to the driver and passenger and completed “field interview” cards that help the LAPD keep track of the people they encounter.

They let the pair go with a written warning for the parking violation.

“It turned out to be nothing, but we didn’t know that until we stopped them and investigated further,” Lankford said.

• • •

Metro’s motto, “Earn Your Reputation,” is carved on wooden plaques hanging on the walls of the division’s headquarters in Westlake.

The officers in the building wear a small “Metro” pin on their dark blue uniforms — the only visible sign of their membership in a highly selective group.

Metro officers must regularly pass rigorous physical fitness tests as well as shooting exams on an array of advanced weaponry. They are the only LAPD officers authorized to work out on the clock.

After a recent downsizing, slightly fewer than 200 Metro officers work crime suppression. About 200 more are divided among other units including SWAT, dignitary protection, K9 and mounted.

In 2015, prompted by a spike in violence, Garcetti had announced that Metro would double in size.

As new officers hit the streets, vehicle stops by Metro rose from a few thousand a year to nearly 60,000 in 2018.

In a city that is 9% black, 49% of the drivers stopped by Metro since the expansion were black, the Times investigation found.

Latinos were 49% of the population and 44% of Metro stops. Whites, at 28% of the city’s population, accounted for less than 4% of the drivers stopped by Metro.

Even in South L.A., the percentage of black drivers stopped by Metro was twice their share of the population, the Times investigation found.

The Times article, published online Jan. 24, noted that there was no proof of racial profiling.

But for some African American residents, the statistics confirmed their personal experiences of “driving while black.” A coalition of community groups demanded that Metro pull out of South L.A.

Garcetti said Feb. 6 that he was “deeply concerned” about The Times’ findings and had directed the police chief to prioritize crime-fighting strategies that reduce the number of vehicle stops.

Until then, Garcetti and other officials had touted Metro as a key reason why crime in South L.A. had recently stabilized.

In a recent interview, LAPD Chief Michel Moore said he is satisfied that Metro’s crime suppression tactics are “not overly reliant on vehicle stops.”

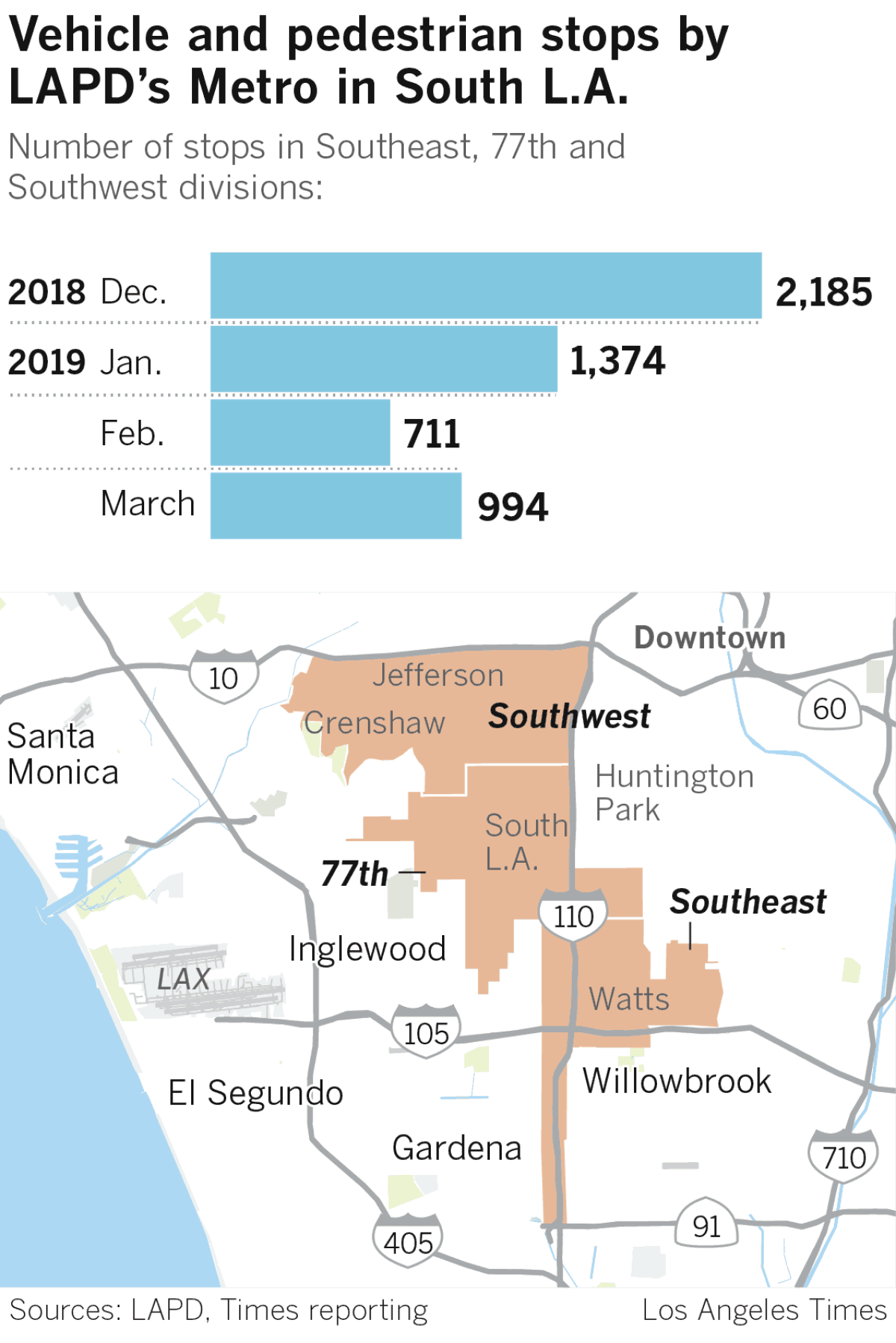

In the weeks after the mayor’s directive, Metro made fewer stops in South L.A. but still stopped hundreds of people, according to figures provided by Moore and verified by The Times using a city open source database.

In February, Metro officers made 711 vehicle and pedestrian stops in Southeast, 77th and Southwest divisions. That compares with 1,374 Metro stops in the same geography in January and 2,185 in December.

Most were vehicle stops, with about 10% involving pedestrians or bicyclists.

Moore said the decrease was due to several factors, including a reduction of about 70 officers in Metro’s crime suppression force as part of a previously planned, department-wide shift of manpower to street patrol from specialized units like Metro.

Another factor, Moore said, was a new emphasis on tracking down specific suspects instead of stopping random motorists.

Last month, the number of stops was up compared with February, with 994 vehicle and pedestrian stops by Metro in the three South L.A. divisions in March, according to a Times analysis of the city database.

Moore personally called leaders of some of the community groups that had urged Metro to leave South L.A., inviting them to a meeting in early March.

“I hear and feel the trauma this has reignited, the injury, the concern that somehow LAPD is slipping back into its old ways,” Moore said.

But as the LAPD adjusts to a different style of policing, Moore predicted that crime will go up.

“I’m working right now to explain that with this balance, we will see upticks and increases in violent crime in South L.A. and throughout the city,” he said.

Alberto Retana, president and CEO of Community Coalition, attended the meeting with Moore, which the chief said would be the first in a series. Retana said his group’s goal remains to get Metro out of South L.A.

“What we’re finding is that African American residents are afraid of police officers, and that break of trust undermines public safety,” Retana said.

• • •

Deputy Chief Dennis Kato boarded an elevator in the LAPD’s South Bureau, arriving at a data nerve center ringed by large flat screens displaying crime maps.

It is a morning ritual for Kato, who leads a daily conference call with station captains to decide where Metro officers will be deployed in South L.A each evening.

There had been a rash of shootings in the LAPD’s 77th Division in recent days. The group agreed to send Metro to the rectangle bounded by South Vermont Avenue and the 110 Freeway, between West Florence and West Manchester avenues.

In an interview before the conference call, Kato said that Metro stops a large number of black drivers because many violent crime suspects are black.

Last year, nearly half the city’s homicides occurred in South Bureau. More than half the homicide victims in that area were black, and about half the suspects were also black.

Citywide, 43% of violent crime suspects were black and 40% were Latino, according to LAPD statistics.

“We’re not sending Metro to Pacific Palisades or West Valley,” Kato said. “Because of where we put them, the stops are going to be blacks and Latinos. Kids can’t get to school safely — that’s why Metro is there.”

If two gangs are warring, for example the Menlo Crips and Van Ness Gangsters or the Eight-Trey Crips and Rollin’ 90s Crips, Kato may send Metro to those neighborhoods to prevent retaliatory shootings.

If black gangs are involved, Kato said, Metro officers will use traffic violations to stop “African American males ages 16 to 24 who dress or look like gang members.”

Last year, Metro officers seized more than 700 guns and made 576 gun arrests, mostly initiated through vehicle and pedestrian stops. Two-thirds of the suspects had prior arrests for assault, burglary, robbery or weapons, according to the LAPD.

“I need them here,” Kato said of Metro. “If they’re out of South Bureau, I guarantee my crime will go up.”

The racial breakdowns in South L.A., with blacks making up 31% of residents and 65% of Metro stops, make sense because Latino gang power has not increased at the same pace as the Latino population, Kato said.

“We’re focusing on gang crime, so we’re going to have more African Americans stopped,” Kato said. “There are more black gangs here. It’s hard to find many Florencias here.”

Tippet, the Metro captain, agreed, saying that Latino gangs are “not that active” in South L.A., while black gangs are “deeply embedded.”

“The victims and suspects are male blacks, a certain age group, there was one vehicle seen, the victims are this gang,” Tippet said over lunch recently. “If I see Grandma running a stop sign, do I really want to focus on her when I want to stop homicides and shootings from occurring?”

Tippet said he is concerned that his officers will shy away from the type of police work now under scrutiny.

“I hope what doesn’t happen is that people stop doing enforcement,” Tippet said. “I live in this city. The last thing I want to see is it overrun by people who want to go lawless and victimize people.”

It is legal for police officers to use a traffic stop as a pretext to look for other crimes. But an overly broad definition of a criminal suspect can raise constitutional concerns, said Peter Bibring, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California and director of police practices for the ACLU of California.

The ACLU of Southern California is part of the coalition calling for Metro to pull out of South L.A.

“What they can’t do is assume that because some people who are black in the neighborhood have committed crimes, that everybody should be stopped,” Bibring said. “That is textbook racial profiling.”

• • •

At a 4:30 p.m. roll call at Metro headquarters, Sgt. Steve Hwang briefed the 14 officers of G Platoon on that night’s mission.

They would concentrate on the part of South L.A. defined by Kato and other officials during the morning conference call.

Hwang described some of the robberies and shootings that had occurred recently.

In one incident, a black male suspect in a black Dodge Charger fired multiple rounds at three male Latinos. In another, black male suspects pulled a handgun on a black male victim, who handed over $1,500 in cash.

The Metro officers would be on the lookout for the vehicles and suspects involved in these and other violent crimes.

Cruising down major thoroughfares in unmarked Crown Victorias or SUVs, they would also stop drivers, bicyclists or pedestrians they saw violating the rules of the road, then look for evidence of more serious wrongdoing.

That night, other contingents of Metro officers were assigned to crime hot spots elsewhere in the city, including Newton Division near downtown, where a USC student had been shot and killed the previous weekend.

Most of the time, Hwang said on the drive to South L.A., officers cannot see the race of the people they are pulling over.

The Times investigation “made it seem as if we’re targeting male blacks,” Hwang said. “I know that to not be the case. Listen for the suspect descriptions — see if you hear male white, male Asian. Do you see that many Asians hanging out on a corner doing crime?”

Hwang, 47, moved to L.A. from South Korea when he was 9. The officers he was supervising that night were white, Latino or Filipino, with no black officers among them.

Overall, Metro was 46% Latino, 37% white, 11% Asian or Filipino and 6% black in September, before the recent downsizing. Five percent of Metro officers were women, compared with 20% department-wide.

After Lankford and Lopez stopped the man and woman on West Manchester Avenue, another pair of Metro officers pulled over a white Mitsubishi Galant because it had paper license plates and a broken tail light.

The driver, a black man, was on parole for narcotics and associated with the East Coast Crips, according to police databases. The officers asked him to step out and handcuffed him.

A Latino male passenger also exited the car and stood on the sidewalk facing a wall with his hands behind his neck while he was patted down at the corner of East Manchester Avenue and South Main Street.

One officer retreated to his car to run the passenger’s name. The other officer rolled up the black man’s sleeves, looking for tattoos.

Because the driver was on parole, the officers had a legal reason to search his car. But his wife and two daughters were with him. He told the officers that the passenger was a friend he had just picked up from the train station.

The officers decided not to hold the man up any longer or to rummage through his car in front of his family. They let him go with a written warning about the vehicle code violations.

“Building rapport, learning a little of their back story — that goes a long way,” Officer Eduardo Ojeda said.

By the time their shift ended at 1 a.m., the officers had stopped 24 cars and two bicycles. Of the people stopped, including passengers in the cars, 25 were black and 10 were Latino.

The officers wrote six traffic tickets, 16 traffic warnings and 27 field interview cards. They did not find any guns or drugs and made a handful of arrests, mostly misdemeanors.

The biggest catch of the day was Lankford and Lopez’s arrest of a black man who was wanted for a commercial burglary. They had pulled him over because his registration was expired and he made an unsafe lane change.

The next night, Metro officers spotted a white Maserati that was linked to a robbery. Inside were a black man, a Latino man and a black woman. The officers believed they were members of the 62 Brims, a Bloods gang based in Harvard Park.

One was arrested in connection with the robbery and the two others for assault with a deadly weapon related to a carjacking.

That night, there were three shootings in South L.A., including one that killed an 18-year-old black man and injured another black teenager. The suspects were described as three or four black men.

To prevent further violence, supervisors told the Metro officers to drive around near the crime scenes and places where retaliation might flare up.

They stayed on the streets for an extra hour until 2 a.m.

Times staff writer Ben Poston contributed to this report.

For more news on the Los Angeles Police Department, follow me on Twitter: @cindychangLA

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.