Opinion: How forgotten Black history has been recovered by rogue scholars

I teach history, but I am not a historian â at least not in a traditional sense. Iâve defended no dissertations and have no Ph.D. But for the past decade, I have been poring over primary source documents, conducting interviews and compiling my findings to create an ever-evolving historical archive.

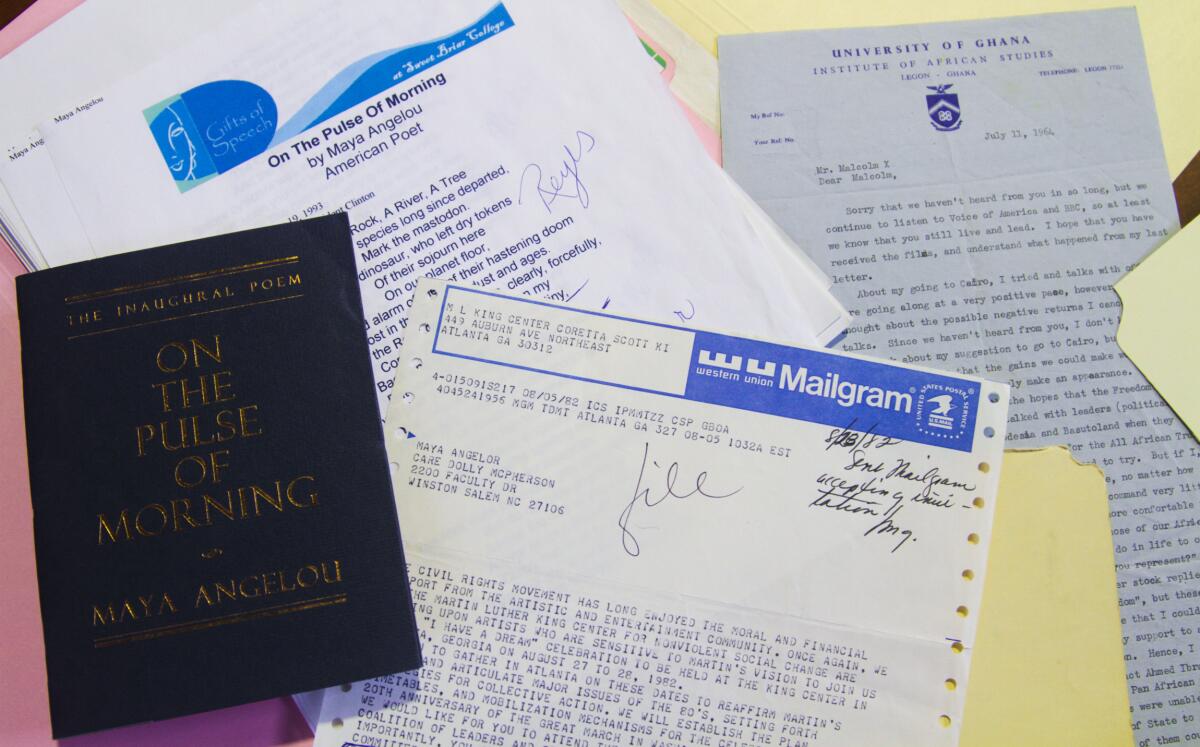

That places me within a long legacy of Black public historians and citizen scholars constructing Black history beyond academia, away from the claustrophobic confines of the ivory tower. Black independent scholars have always existed, driven by a desire to recover lost narratives â while redefining what it means to be a historian.

Institutional racism has long excluded Black scholars from the academy. Out of almost 2,000 history doctorates awarded by 1935, only six were given to Black people. The desegregation of public schools in the 1950s, â60s and â70s included colleges and universities, meaning that until that era, Black students were locked out of many of these institutions. As a result, the white men who maintained a monopoly on the subject have dictated a vast swath of American history. These have been the authorities gatekeeping our understanding of the past. They have had the most years of access to backroom archives, special papers and original documents and been best-positioned to get lucrative grants and funding from endowments.

Why do we even still have Black History Month? The growing number of right-wing attacks on teaching Americaâs racial history offers a good answer.

Even in more recent years, within a still largely unequal history field, it is primarily white scholars who gain access to subscription-only services distributing millions of digital books, documents, photos and journals for research. Where they find an open door to the past, Black scholars have often stood keyless, in front of a closed door with a deadbolt.

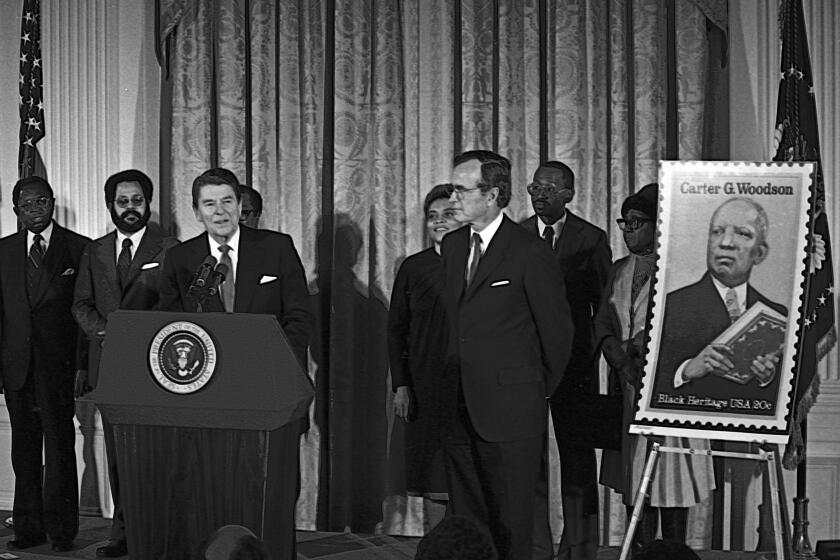

Yet rogue scholars have still managed to uncover hidden history. One was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, who in the early 20th century became one of his eraâs most meticulous curators and scholars â and did so without an advanced degree. Eventually, his prolific collection laid the foundation for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, currently part of the New York Public Library. One longtime director of that center said that Schomburg amassed a collection in part to dispel white myths of Black inferiority and to show that Black people had history and culture, which had largely been ignored. Despite having to work in segregated libraries, Schomburg and many of his peers built on one another to create an interconnected Black historical universe.

So much has changed, and yet so much has stayed the same. One disheartening analysis found that only 7% of U.S. history professors are Black, and that Black scholars have the lowest average salary compared to any other racial demographic of history professors. This speaks to the ways Black voices continue to be marginalized despite our being part of Americaâs cultural fabric.

The challenges donât stop there. Black historians have often found the support missing within traditional history departments in the African American studies field â which is under assault, with Florida rejecting the College Boardâs Advanced Placement African American studies class and other states now scrutinizing the course.

To quash the teaching of racism, books by Black writers are being banned. As a âhate the book, hate the writerâ ethos takes hold, weâve become targets.

Such barriers could have caused many to give up â but curses can also be gifts. Exclusion unintentionally created space for Black public historians to tell history on their own terms, without the restrictions and limitations â including misconceptions about Black stories â imposed by the profession. As a result, these historians have fostered a direct and authentic engagement with those whose stories they are documenting. My research focuses on telling the stories of historically unheard people often left out of U.S. narratives. While working with schools, public institutions such as libraries and museums and directly with communities, I have seen firsthand how learning about the past can enrich peopleâs lives.

The stories told in textbooks, museums and other educational materials can profoundly impact how we view ourselves and our society. If Black historians are not granted the recognition and support they need â and deserve â the historical record will remain incomplete, and our understanding of our collective past will remain limited.

This can be done by universities and other institutions funding and supporting community-based historical projects, creating more inclusive academic departments that recognize and celebrate Black historiansâ contributions, and promoting civic scholarsâ work through independent publishers and social media. Black public historians have already played a vital role in documenting the past. We should support these efforts to keep uncovering the rich stories of Black history â and to support the broader definition of a âhistorianâ that they exemplify.

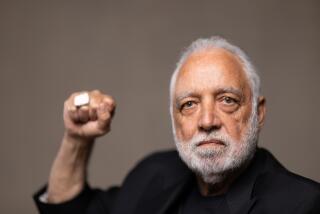

Jermaine Fowler is the founder and managing editor of The Humanity Archive and author of the forthcoming book âThe Humanity Archive: Recovering the Soul of Black History from a Whitewashed American Myth.â

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.