- Share via

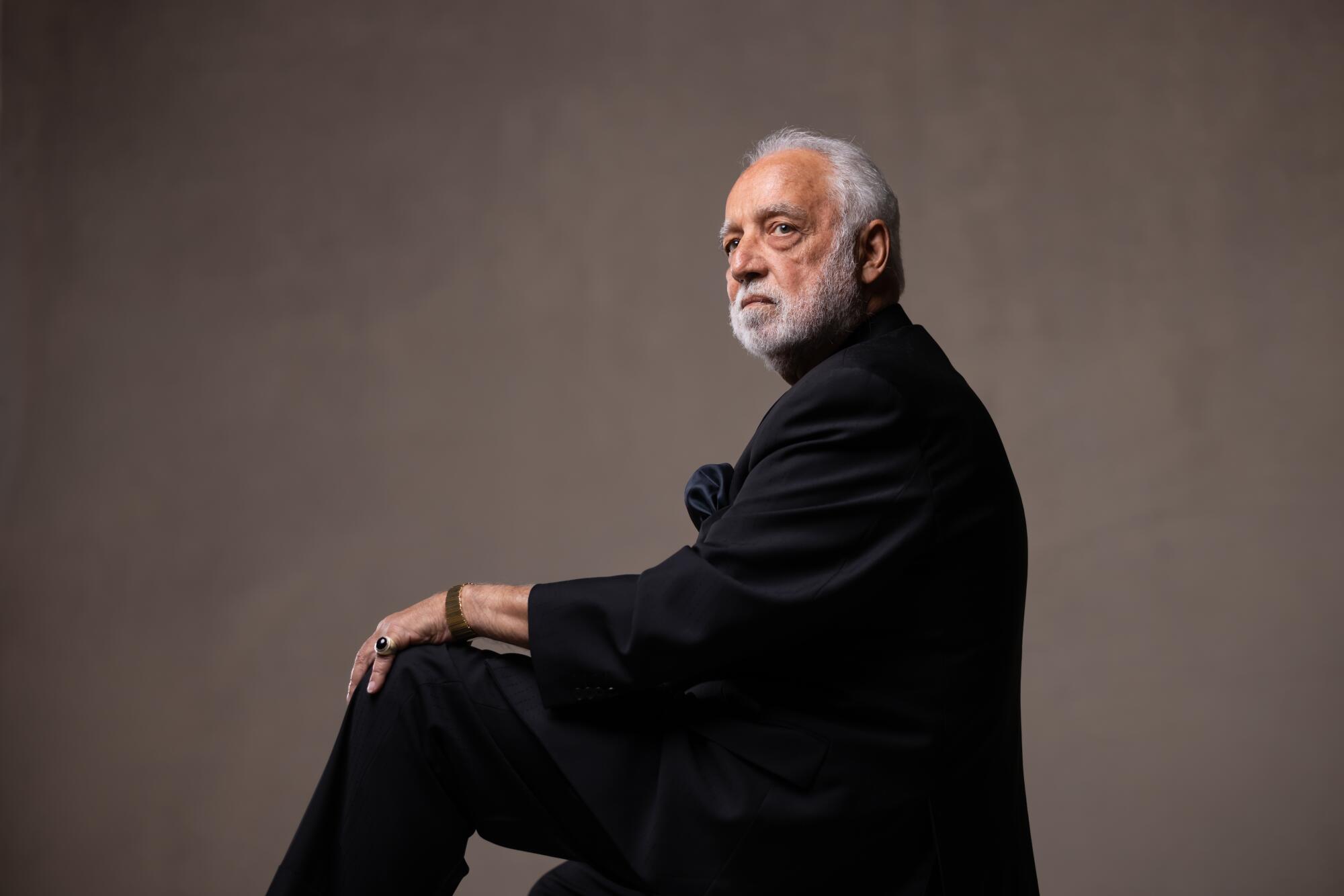

It was the tail end of the Great Migration when Danny J. Bakewell Sr. left New Orleans for Los Angeles in 1967. He was 21; a college dropout with a wife and a baby, in an era of dismal prospects for Black people.

He would have taken any job here that paid the bills. What Bakewell didn’t envision was that the one he got — a community organizing gig — would set him on a path to power, as a civil rights leader, a property developer, a business tycoon and publisher of the Los Angeles Sentinel, the city’s legendary Black newspaper.

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. L.A. Influential brings you the moguls, politicians, artists and others telling the story of a city constantly in flux.

After the segregation of the South, it didn’t take Bakewell long to realize that the City of Angels had its own racial hierarchy — one that stranded Black people in dilapidated enclaves with poorly-resourced schools and brutal policing.

Bakewell’s mantra was self-determination, and he began rallying residents around that ideal in the late 1960s. “We did not want anybody to give us anything,” he said. “We were willing to work for it, and we were willing to rely on each other for our future.”

A few years later, he was hired to lead the Brotherhood Crusade, a grassroots organization that refused to take government money and financed its self-help programs with voluntary payroll deductions from Black folks’ paychecks.

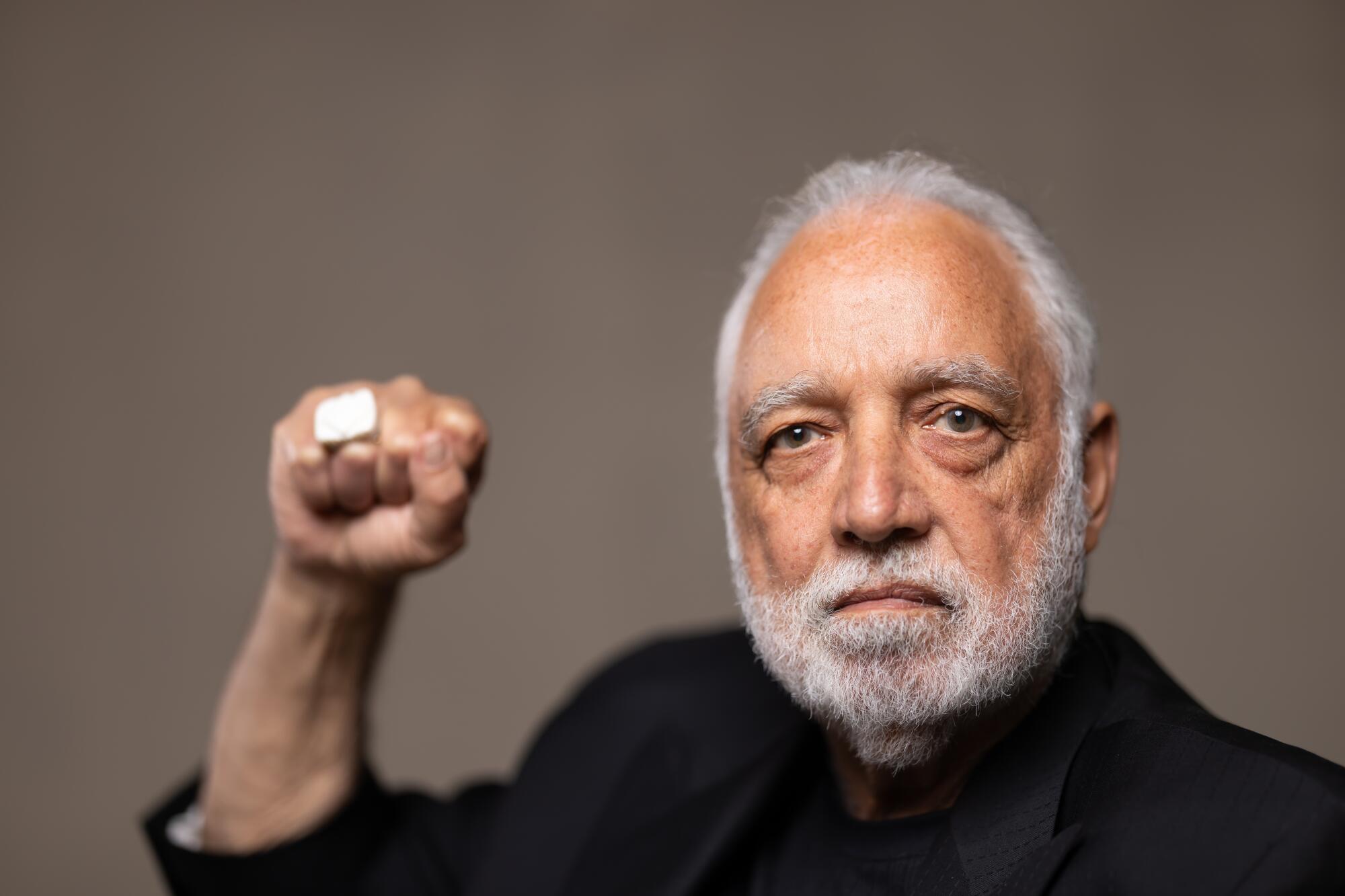

‘I am for Black people for sure. That’s who I come to the table to serve.’

— Danny J. Bakewell Sr.

That high-profile role raised Bakewell’s visibility citywide, giving him a license to operate from the halls of power to the city’s most troubled blocks.

He has the ear of politicians — including Mayor Karen Bass — and the respect of communities he won’t allow to be overlooked.

“Danny is always asking, ‘What can we do, brothers and sisters, to help out?’” said Khalid Shah, head of the Stop the Violence, Increase the Peace foundation.

Bakewell, 77, helped legitimize a movement that turned gang members into peacekeepers who helped tamp down violent crime. He brought commercial development to Compton’s sagging downtown. And for 18 years, he has hosted the biggest family-friendly food and music festival on the West Coast, Crenshaw’s “Taste of Soul.”

Still, Bakewell’s climb up the civic ladder didn’t come easy. His single-minded focus on Black issues and refusal to compromise made some people uncomfortable.

“I’m not against anybody,” Bakewell has always insisted. “But I am for Black people for sure. That’s who I come to the table to serve … because I see us always left out, always left behind.

“And if I’m going to have any role of leadership, I want it to improve the lives of Black people.”