Op-Ed: Connecting with Kafka during our pandemic isolation

- Share via

This past fall, as Duke University faculty and students approached remote learning with uncertainty and apprehension, a past student of mine made a request. He had enjoyed my seminar on modernism last year, he said, but he was disappointed that it had not “changed his life.” He was looking for some kind of transformative experience through literature, and my class had failed him.

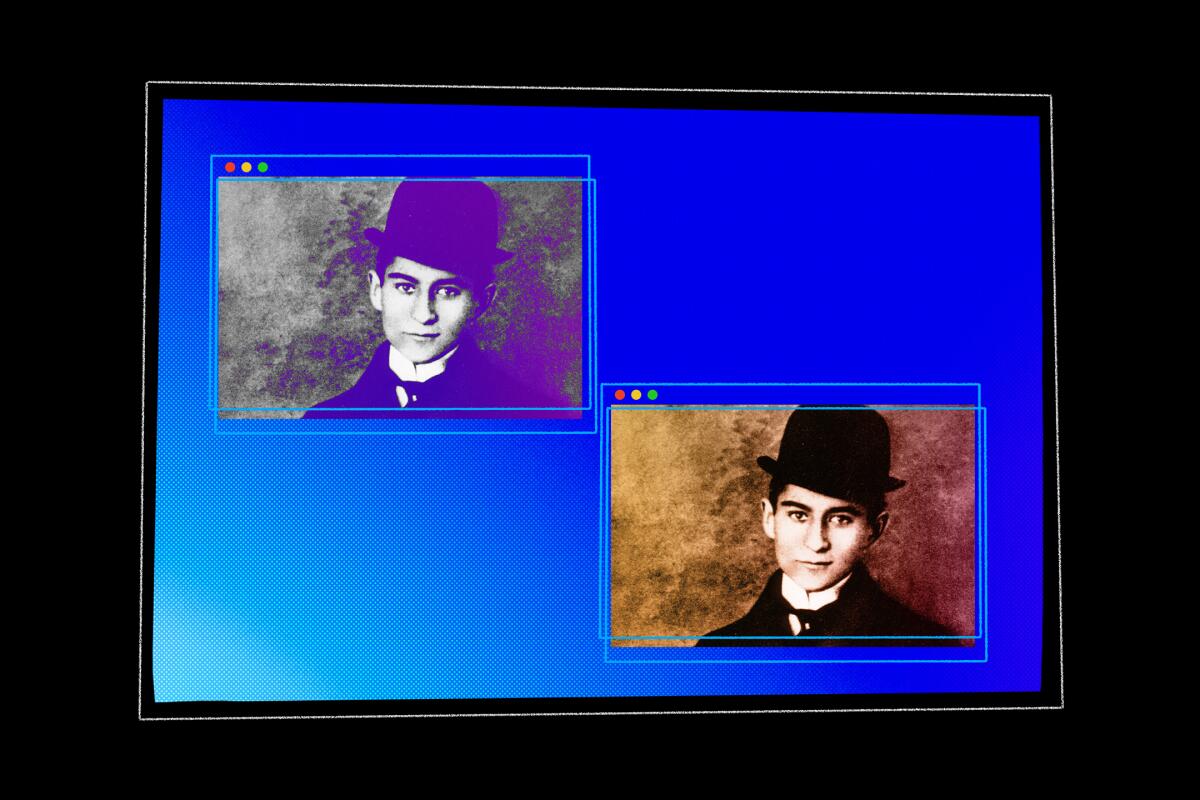

Perhaps sustained immersion in the work of a single author, I suggested, would help him reflect on the very idea of “transformation” or “change,” and what that can mean. He asked if we could read Franz Kafka together.

I said yes, immediately thinking that much of the Czech writer’s work explores change: It features, such as in “A Hunger Artist” and “In the Penal Colony,” characters who resist, with fatal outcomes, the transformation of the world. It lingers on the aftermath of Gregor Samsa’s abrupt, shocking transformation into a large insect in “The Metamorphosis,” and on the slow, painful ordeal of young Joseph K. as he becomes the shadow of himself in “The Trial.”

Much of the isolation of that semester thus was filtered through the experience of reading Kafka over Zoom. The experience made a particular feature of his work more salient than it might have been if we had met in person: the disquieting varieties of a ruminative solitude, particularly resonant during pandemic isolation.

The first time we realized this was upon stumbling across a message scribbled by the young Kafka on a postcard to his friend Max Brod: “I am in such a bad way that I think I can only get over it by not speaking to anyone for a week, or as long as may be necessary. From the fact that you won’t try to answer this postcard in any way, I shall see that you are fond of me.” The request to be left alone as a token of affection struck a chord at a time when staying away from loved ones had to be rethought as a gesture of protection.

But Kafka’s note also captures a disturbing unsociability I felt at times during the pandemic, when my discomfort with what was going on in the world had reached such a low point that I avoided meeting friends, even socially distanced, to spare them my anxieties. On a different occasion, when a friend apologized for not wanting to go for a walk, I sent him Kafka’s passage as a way of telling him I understood.

The story of “The Burrow” hit close to home during that tumultuous semester. The creature’s burrow, which can be understood not only as a dwelling, but also as a physical representation of the meanings we attach to our lives, was disrupted and turned unrecognizable by the intrusion of an invisible, insidious beast. COVID-19 was our beast: It interrupted our lives in a sudden and complete way, casting us all as anxious characters in a Kafka parable.

Perhaps nowhere is this theme of disruption more palpable than in “The Trial.” Joseph K. torments himself trying to figure out what he is being accused of. Why not write, he thinks, a preemptive defense, “a short description of his life [to] explain why he had acted the way he had at each event that was in any way important, whether he now considered he had acted well or ill, and his reasons for each.”

This is a life examined relentlessly to a pathological extreme when one is removed from the company of fellow human beings. It’s the kind of compulsive self-examination that occurs when what used to be normal can no longer be taken for granted.

In such times, literature gives readers ways to grapple with extreme uncertainty. Whether fictional or real or somewhere in between, stories illuminate the vast possibilities of existence. They offer insight into what might be, or might have been; into lives we might have had, had some of the circumstances been altered; into what things are like when what we take for reality takes an absurd turn and life becomes fiction-like.

It was this picture of literature that gained solidity in my mind as I thought of the graduating seniors. In their last year, they had shown resilience and persistence in continuing to read, to study, to show up for class in front of their laptops. They continued to be engaged in precisely the kind of activity that enabled them to figure out what it takes to adapt to unprecedented and unpredictable change.

Through our independent study, my student and I came upon unsettling forms of loneliness, isolation and unexpected change in the Kafkaesque landscape we explored. A hundred years before us, Kafka offered us a revealing window into the current strangeness of our lives.

Corina Stan is associate professor of comparative literature at Duke University. She is the author of the book “The Art of Distances: Ethical Thinking in Twentieth-Century Literature” and of essays such as “Between Us: A History of Social Distance” and “On Tact in Dark Times.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.