- Share via

A woman pulls into a desert town at sunset. A writer sees her mother rooting through a dumpster. A Herald of the Almighty stumbles upon a dying stone monster, and a businessman admits to the shame of being a businessman.

Pages of books slowly turn. Readers have fallen under their spells.

They made their reservations days in advance, found their way to a coffee shop in Silver Lake, where they greeted their host, paid $17 and quietly let the world outside slip away.

Rain falls on Lake Geneva, 1816. A Buddhist monk remembers a monastery in Thailand. A children’s author recalls playing beneath tables and inside forts.

The readers number just shy of two dozen. They have scattered throughout the bright early evening space — “closed for a private event,” the sign outside reads — slouching in upholstered chairs or along a bench, leaning over small tables, sitting alone or with a partner.

The Silver Lake Reading Club — every Tuesday evening, 6 to 8:30 p.m. at Lamill Coffee — is now in session.

Few activities are as simple and complex as reading. Neuroscientists have charted the mind’s incantation of words that lights up the temporal lobe, the frontal lobe, ridges in the cerebral cortex, triggering impulses that transform squiggles of ink into letters, letters to words, words to sentences and meaning and comprehension and empathy.

The magic is learned in childhood — from Clifford, hungry caterpillars and pigeons that shouldn’t drive buses — and once mastered, is taken for granted. For many adults, the skill is saved for practical purposes: recipes, owner’s manuals, street signs, websites or newspapers like this.

Reading for pleasure is increasingly rare. Battles must be fought to find time and to quiet the monkey mind of modern life.

“I’m still in shock at how popular this has become,” said Helen Bui, the reading club’s founder and organizer. “Even though we’re selling out every week at this point, I still can’t believe it has become a thing. I’m in awe of it.”

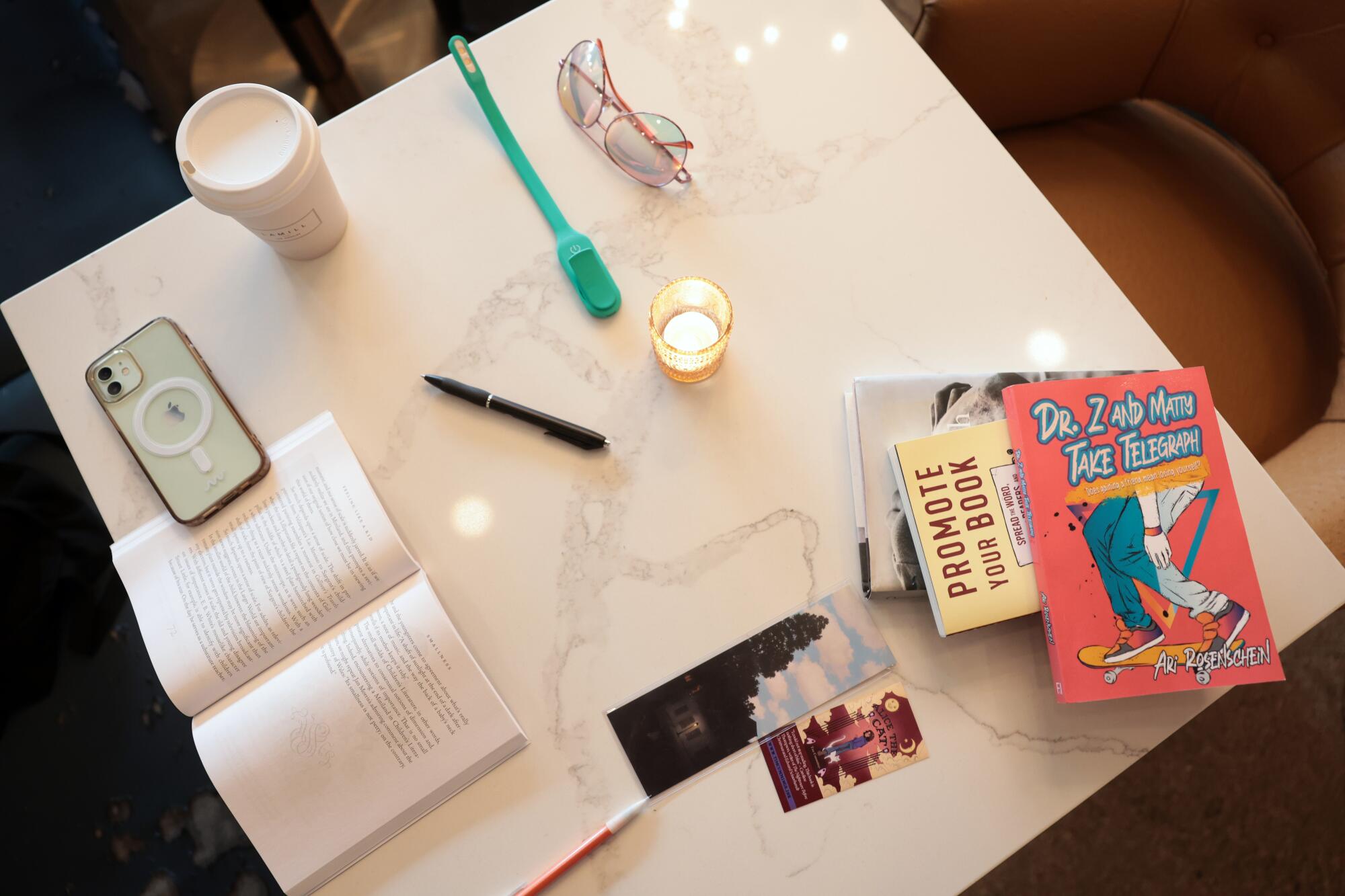

Bui, a youthful 42 (blue jumpsuit, Dodger cap, blond hair, glasses), sits near the front door greeting arrivals. She takes out her phone for a picture of everyone with their books — actual books, for only a very few read off phones or computers.

Bui’s vibe is part librarian good for a recommendation or two and part yoga instructor eager to set the mood for everyone’s practice.

She’s cued a piano melody to play softly in the background. She’s set small tea lights on each table. She’s laid out brownies and lemon and currant loaves that she baked hours earlier.

Sunlight lances through the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Silver Lake Boulevard. Commuters crawl home through the traffic. Dogs and their humans stroll by. Students gather for mat work at a Pilates studio, and early birds tuck into shellfish at a neighborhood oyster bar.

So much of L.A. life is about coming and going, but the readers here inhabit an in-between space where motion has stopped and time is suspended, filled with the wonder, anger, humor and passion of writers — Paul Murray, Thich Nhat Hanh, Kurt Vonnegut, David Sedaris. They sip coffee or tea included in the price of admission and nibble at the snacks that Bui has brought.

Daughter of Vietnamese refugees, Bui grew up in Los Angeles, worked as a business manager for the Wall Street Journal and News Corp., and at 32, having attained the dream (“an immigrant and successful”), she realized she was unhappy and she quit.

Living abroad for a few years, she came home during the pandemic, first to San Francisco, then back to L.A., finding an apartment in Silver Lake, where she writes cookbooks, fiction and, every three months, her obituary.

A cancer survivor (breast, BRCA gene), she reflects on who she is, how she wants to be remembered, what she’d like to leave behind — and that includes this moment of reading.

The idea came to her late last year, and she started looking around for a location. The public library closed too early. Some coffee shops were too trendy. Lamill seemed perfect: the space, the aesthetic and the seating. “The chairs aren’t steel,” she said, “like they want you to leave.”

Silent reading groups are not a new thing. Perhaps the most well-known — the Silent Book Club — dates to 2012, when two friends in San Francisco, Laura Gluhanich and Guinevere de La Mare, met at a local bar and started reading.

Begun on the premise that book clubs were too restrictive and too chardonnay-focused, they wanted to provide a space where there was no assigned reading and everyone was welcome. Today, the trademarked Silent Book Club has close to 1,100 chapters worldwide, on every continent except Antarctica.

“Finland is blowing up,” said Gluhanich, who while amazed by the growing popularity of these groups, gives the pandemic and lockdowns a little credit.

The ubiquity of silent reading groups doesn’t detract from this novel moment.

A man has murdered his family. A skeleton is found at the bottom of an old well. “The beauty of Earth is a bell of mindfulness.”

Christina Raquel, 29, has just begun “A Gentleman in Moscow.”

At half past six on the twenty-first of June 1922, when Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov was escorted through the gates of the Kremlin onto Red Square, it was glorious and cool.

A development executive for a Culver City production company, Raquel lives just up the street; this is her third time with the reading group, a chance to step away from other books at home vying for her attention, from her computer, work and Frankie, her Pyrenees Chow mix. She wrestled with the idea of paying for the chance to read when reading is free.

“But the financial investment keeps me focused,” she said, and because this is a communal setting, she is less likely to pick up her phone, which is not as easy as it sounds in the age of digital distraction. Plus she likes reading a book, not a screen, savoring the words, not breezing through content.

“I’m training my brain to read like I did when I was growing up,” she said, “and to save what’s left of my attention span.”

In “Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity” — which isn’t being read by anyone tonight — Gloria Mark describes sitting behind people in their offices with a stopwatch in hand, click-clicking each time they switched computer screens or picked up a phone.

Once, her subjects stayed focused 150 seconds before switching tasks; eight years later, that was cut in half.

The club’s reading time is divided into two 45-minute sessions, with a 15-minute break for stretching, chatting, a little more nibbling. During another 15 minutes at the end, readers share what they’ve read.

Their books are their calling cards, signals of taste and interests (spiritual, historical, popular, esoteric) that link the private with the public. Forget swiping right; this is the prospect of a post-pandemic meaningful encounter. (At least one club has a story of a reader coming alone, then bringing a boyfriend who became a husband, then becoming parents together.)

The club is also an escape — from everyday interruptions, guilt and temptation, families, roommates, babies and pets — and a chance to surrender to the promise and tease of the first sentence of a new book.

Why is there so much poverty in America? I wrote this book because I needed an answer to this question.

So did Nina Suarez, who brought Matthew Desmond’s “Poverty, by America” and quickly saw herself in its pages, in particular a passage about “the degradation rituals of the welfare office, where you are made to wait half a day for a 10-minute appointment with a caseworker who seems annoyed you showed up.”

Reading those words on page 20, she paused, flooded with memories of going to the housing office on Wilshire Boulevard with her parents and four brothers to qualify for a Section 8 voucher, an experience that was both humiliating and humbling.

Suarez, 38, had heard of other reading clubs — one in Burbank, one in the South Bay — which are a little too far from home in East Hollywood, or her work at a mental health nonprofit in L.A. Tonight is her second time.

“Post-pandemic, we’ve all been reclused for a little bit, so it’s nice to get out, connecting and creating community,” she said.

By entering this space, she left behind “the white noise” of her duplex, the neighbors with their televisions on, the families next door coming and going, her own anxious thoughts about work and life.

Outside, night is falling. Traffic has grown lighter. Across the street, the 7-Eleven’s fluorescent glow brightens the darkness.

Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight” is playing. Mirrored walls and lavish chandeliers provide the lighting. Occasionally, a page is turned loudly enough to be heard.

A sister tells her brother about the time she saw a lady with a monkey in a Starbucks. A widow corrects the record about her dead wife. A writer broods on her reading habit: What is it about, what am I doing it for, what is it doing for me?

Long, long ago, such an activity was unimaginable. The written word on scrolls, tablets and early books — in the ancient empires of the Fertile Crescent, in Greece and Rome and the West through the Middle Ages — was mostly intended to be spoken, to be read out loud.

Scholars — see “A History of Reading in the West,” edited by Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, and “A History of Reading” by Alberto Manguel — speculate that libraries were filled with the voices of readers in what must have been a strange cacophony. While there were exceptions, not until around the 10th century did the practice of silent reading become more common.

This inward shift, this internalization of an author’s voice, was made possible by the gradual standardization of punctuation, which allowed writing to become less dependent upon the cadences of speech and gave writers the freedom to explore more private realms of thought.

Readers were suddenly exposed to political tracts, memoirs, make-believe and erotica. The world was forever changed.

At 8:15, Bui stands in front of the coffee bar with a faux jewel-encrusted karaoke microphone.

“Now,” she says, “is the time to share.”

Gabby Sharaga stands. She and Bui are friends who met at Lamill last summer. Tonight, her dog Milo and her never-ending to-do list will have to wait.

Sharaga, 33, introduces herself as a counselor at a continuation school in the Valley. She had seen “Civil War” over the weekend and wanted a book that was uplifting. “There’s no end to the end-of-the-world books,” she says.

She reads aloud a passage from “This Time Tomorrow,” Emma Straub’s novel about a woman who, on the eve of her 40th birthday, wakes up to find herself 16 and given a chance to start over — but with all the knowledge she’s gained.

Maybe that was the trick to life: to notice all the tiny moments in the day when everything else fell away and, for a split second, or maybe even a few seconds, you had no worries, only pleasure, only appreciation of what was right in front of you.

“This is a reminder to live life with more joy,” Sharaga said into the microphone. “Soak in every moment.”

Others share passages that spoke to them, and everyone listens intently. The room’s hush somehow feels preserved.

At 8:30, Bui thanks everyone and announces that in two weeks — with the approach of summer — they’ll be meeting outside in Lamill’s pixie-lit patio.

The readers stand and wander dreamily out the door, back into their lives.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.