Op-Ed: Don’t let time shield sex predators

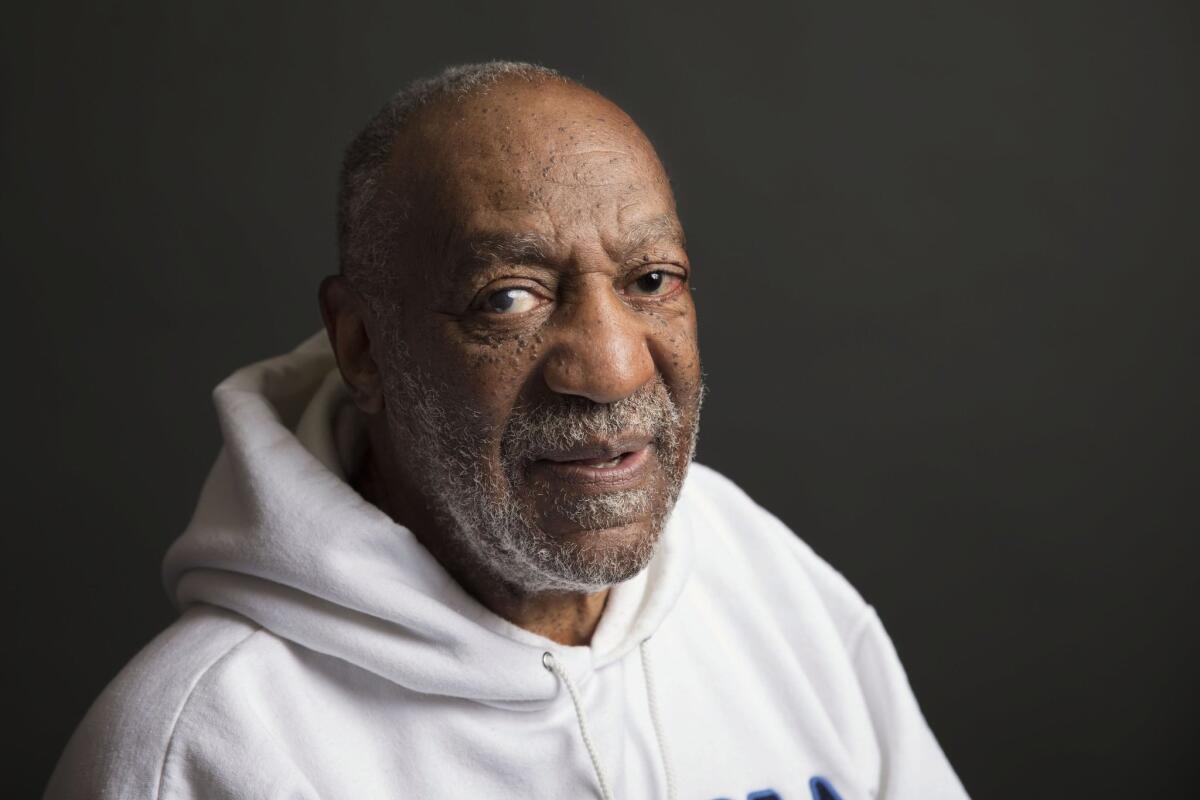

Actor-comedian Bill Cosby poses for a portrait in New York. Cosby has been accused of sexual assault by dozens of women over a period of decades. Some of the women who accused Cosby of sexual assault have run up against the time limit and have turned to defamation suits as an alternative way to obtain some modicum of justice.

When I was between the ages of 15 and 17, I was sexually abused by one of my high school teachers in Orange County. By the time the abuse ended, I was pregnant and had a sexually transmitted disease.

It took me years to understand the extent of my abuse and recover enough to come forward, but by that time, the criminal and civil statutes of limitations had expired. Even though I had evidence that my choir director had sexually assaulted me, there was nothing I could do to stop him from targeting other vulnerable teens.

Victims should have no deadline.

California has abysmally complicated sex crime statutes. Child victims abused before Jan. 1, 2015, have until age 28 to file criminal charges and 26 to use the civil courts (with some exceptions for those who meet a high burden of proof). Minors abused after that date (or who didn’t hit the time limit by that date) have until 40 to file criminal charges and 26 for civil charges, again with exceptions.

For adult sexual assault victims, there is no limit for aggravated sexual assault — that is, when the assailant uses a weapon or there are multiple assailants. For “normal” sexual assault, adult victims usually have 10 years to file criminal charges, unless there is DNA evidence, which can give victims more time. The limit for sexual assault civil cases is two years from the date of the occurrence.

In my own case, my deadline for criminal charges was age 24. I could use civil law only until my 19th birthday.

These relatively short time frames mean that wrongdoers like my teacher, and far more famous people accused of abuses, such as Bill Cosby, can avoid seeing the inside of a courtroom. Some of the women who accused Cosby of sexual assault have run up against the time limit and have turned to defamation suits as an alternative way to obtain some modicum of justice.

Why are victims of sexual abuse given arbitrary — and downright confusing — deadlines for coming forward? How many predators are roaming our neighborhoods, unknown to us because their victims have been denied the right to hold their abusers accountable?

At least the solution is easy: California should comprehensively eliminate time limits for prosecuting sex crimes. Law enforcement shouldn’t have to refer to a graph to determine whether a victim of sexual assault has legal rights. Victims should have no deadline.

Other states have moved in this direction. Delaware, for instance, eliminated the criminal statute of limitations for child sexual abuse victims in 1992, and eliminated the civil equivalent in 2007. The same can be done for adult victims.

California’s lawmakers seem aware that the current system makes no sense.

In 2003, in the wake of the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal, the Legislature gave child victims a one-year window to come forward, no matter when the abuse occurred. Why would they have done that unless they recognized that deadlines are bad policy?

The “window” meant that victims like me had the right to use the civil courts. I exposed my abuser and was able to publicly release documents from my case, including my abuser’s signed confession stating that he had sexually assaulted me and at least two other girls.

In 2013, the Legislature revised the 2003 law to give victims who missed the window an additional two-year grace period. The bill passed both houses, but Gov. Jerry Brown, at the behest of the California Catholic Conference, vetoed it.

I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to file suit against my accuser, but livid that other victims are denied the same.

According to the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault, it can take victims decades to become strong enough to report. Reasons for delay can include shame, self-loathing and fear of not being believed.

I spent 15 years blaming myself for my abuse. My peers, my parents and school officials convinced me that I had not been raped because I didn’t go to the police right away. They convinced me that I “wanted it,” not realizing that I had been carefully groomed for abuse. I hated myself for a decade; I thought I was a bad person. But eventually I came to understand that no child from an alcoholic home stands a chance against an adult sex predator.

Adult victims need time too. Consider the Cosby scandal. Until the spate of news stories in 2014, who would have believed that “America’s Dad” might be capable of such crimes? What woman could have the strength, and the bankroll, to take on one of Hollywood’s most beloved figures? Now that the public’s ready to believe, these women’s access to the courts is severely limited.

Opponents of reform are quick to say that, over time, evidence is lost, witnesses move away and memories fade. But no one’s arguing that sex abuse victims shouldn’t have to prove their accusations — they should just have the right to try. If there is truly no evidence, the courts can refuse to hear the case.

Joelle Casteix is the volunteer Western regional director of SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, and the author of the book “The Well-Armored Child: A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Sexual Abuse.”

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.