New skyscrapers vie for West Coast’s ‘tallest’ title

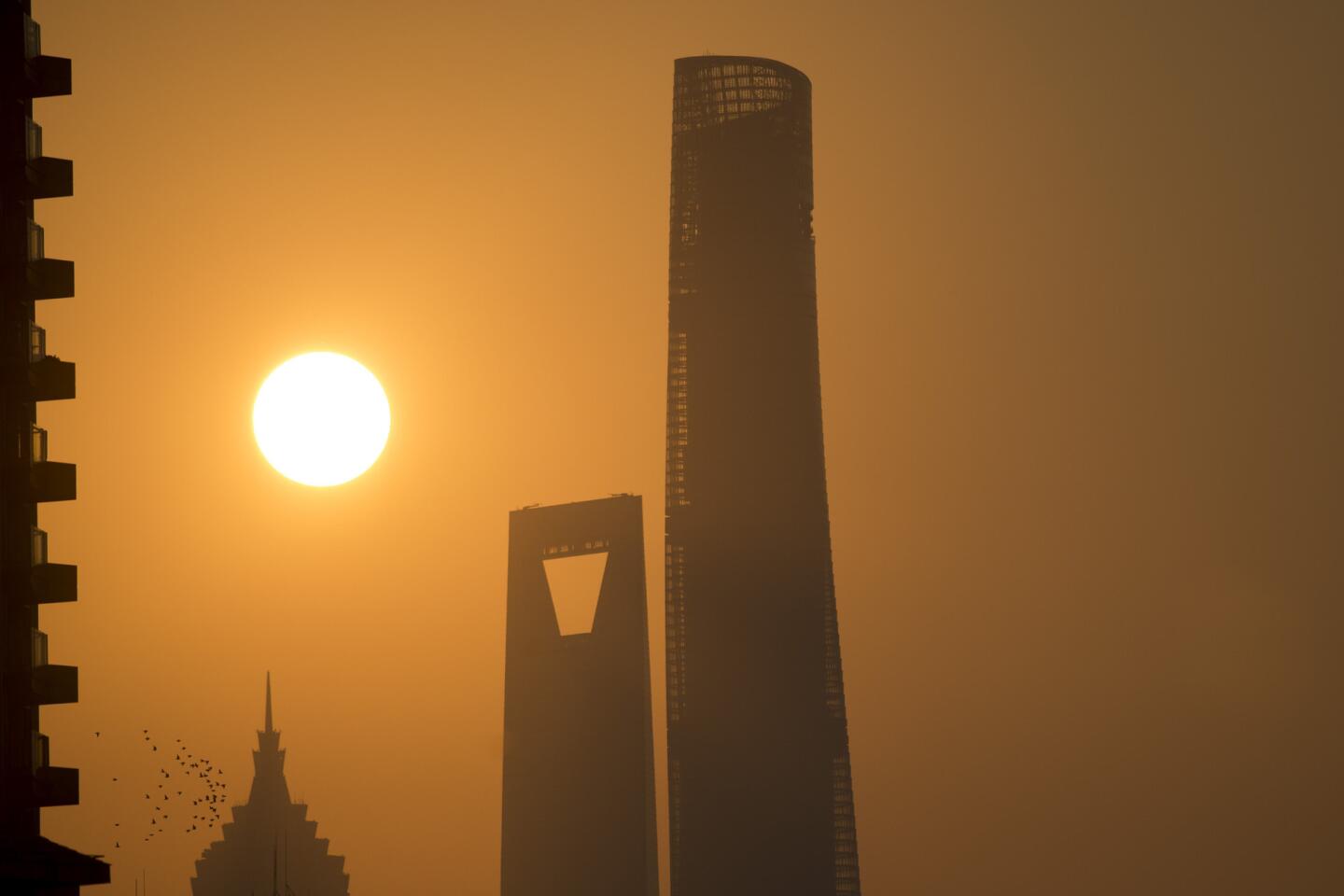

When the Wilshire Grand Center, left, is completed next year, it will eclipse the U.S. Bank Tower, center, as the tallest building in Los Angeles. It will also be the tallest in the West -- for a while.

- Share via

Reporting from SEATTLE — At 1,018 feet high, the 73-story U.S. Bank Tower in downtown Los Angeles holds title to the West Coast’s tallest building, a crown it is now destined to lose. Over the next few years, at least three other coastal skyscrapers under construction or on the drawing board are set to soar past the bank tower by as many as 30 stories, with the “tallest” title probably going back to Seattle.

It’s a western boomlet of skyscrapers, reflecting a strong economy, a demand for more lofty digs, and something of a size-matters competition among developers and cities.

Developers of a Seattle tower, in their city application, have sought what they called a height “sweet spot” — between 1,050 and 1,150 feet — to gain matchless views of the region’s soaring topography, Mt. Rainier and the snow-capped Olympic Mountains. Bigger was not only better, it would be breathtaking.

That was the message, on steroids, when the world’s tallest building, the 163-story Burj (Tower) Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, opened in 2010. Built in large part to gain international recognition, the 2,722-foot skyscraper, shaped like pyramiding stacks of coins (it cost $1.5 billion to erect), owns all the height records one could think up, including world’s highest nightclub (143rd floor), world’s highest mosque (158th floor) and world’s fastest elevators (40 mph). From its observation deck, you can see Iran.

West Coast developers are thinking smaller, by almost 1,700 feet, yet taller than they’ve ever attempted.

San Francisco is poised to take the height title from Los Angeles next year when the 1,070-foot Salesforce Tower is to be completed, topping the U.S. Bank Tower by 52 feet. Shaped like a blunt-nose missile, the glass-wall skyscraper will loom over the $4.5-billion Transbay Transit Center, the city’s new South of Market transit hub. The planned site of future high-speed rail to and from Los Angeles, the Transbay is being heralded as the “Grand Central Station of the West.”

But San Francisco may lose out in the height battle to L.A. before the Salesforce Tower is completed: The 1,100-foot Wilshire Grand Center (including a 100-foot-plus spire), a $1.2-billion, mixed-use office/hotel project in the Financial District, is also set to be completed next year, probably in the spring. Developed by Korean Air, the tapered, glass-walled skyscraper will be topped by a domed “sky lobby” with views of the Southland. It will reach 30 feet higher than the Salesforce Tower and become, developers say, the tallest building west of the Mississippi.

For a while.

On the drawing board in Seattle is the West’s first 100-plus story skyscraper, know as 4/C. It would top the Wilshire Grand by 11 feet.

What’s driving buildings upward? Demand, for one.

“The Wilshire Grand Center and 4/C tower in Seattle are going to be mixed-use projects, with some combination of apartments, hotels, offices and shopping,” said Jason Barr, an associate professor of economics at Rutgers University-Newark. “So given the favorable climate for these high-end mixed uses, and the cache that being ‘tallest’ brings to the market, I would say that the appearance of these buildings suggests that developers are trying to exploit a demand opportunity.”

The prestige of breathtaking panoramas pays off for both developers and customers, Barr added. “Super-tall projects can earn the developers premiums above more typical high-rise buildings if they convey some useful information or provide other services not available in other buildings,” said Barr, who studies skyscraper economics and is the author of “Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers,” due out shortly.

“In the case of offices, high-powered firms are often willing to pay the higher rents in these buildings because it advertises their profitability. In the case of luxury condos, very wealthy residents are also willing to pay a premium to live in these buildings, as a form of conspicuous consumption or investment,” he said.

Advanced construction technologies are also making skyscrapers more feasible, taller and safer, said Jason Gabel, a spokesman for the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat in Chicago.

For example, “Super high-strength concrete is a major advancement that provides high strength, high stability, high pumping performance, low heat, low shrinkage, low cost, self-curing, self-compacting and self-leveling,” he said. “This material has been instrumental in realizing tall buildings in very active seismic regions, as it provides superior performance against lateral loads.”

Perhaps more than anything else, it is the statement implied by an edifice that looms over an entire cityscape.

“Architecture is extremely communicative,” said Gabel, “and building 1,000-plus-foot towers is sending a very clear message to the rest of the country and around the world that these are successful, bustling, energetic places to live. So there is definitely a ‘look at us’ element to this phenomenon as well.”

At this point, Seattle’s proposed skyscraper could emerge as the new Western height leader as soon as 2018. The plan is to include 1,200 luxury residences, 150 hotel rooms and 165,000 square feet of retail and office space.

“The scale of this building is actually related more to creating the appropriate amount of space — through a broad mix of uses — to activate and animate the neighborhood,” the developer, Miami-based Crescent Heights, says in plans filed with the city.

The Seattle edifice would rise 102 stories on a narrow parcel that is just a few blocks from what was the coast’s tallest building when it opened a century ago — the 42-story Smith Tower, completed in 1914 by typewriter magnate L.C. Smith, of Smith-Corona acclaim.

The building that Smith never got to see — he died before its completion — hung onto its coastal crown for almost half a century, until the 1962 topping-out of the 665-foot Space Needle for the Seattle World’s Fair. Today, at just under 500 feet high, the Smith Tower’s pointy rooftop pokes up vainly among a forest of modern steel-and-glass high-rises, at least 15 of them taller and built mostly in the last few decades.

If Seattle is to surpass the 100-story mark, however, it must first overcome Federal Aviation Administration objections. The agency told the developer the very reason for building the skyscraper is the reason it can’t be built: It’s too tall.

An FAA “notice of presumed hazard” was issued to Crescent Heights last month, stating that a building that high on the hilly downtown parcel now occupied by a parking garage “would have an adverse physical or electromagnetic interference effect upon navigable air space or air navigation facilities.”

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

It was a complication similar to that encountered by Seattle mega-developer Martin Selig, who opened what was then the coast’s tallest skyscraper, the 76-story, 943-foot Columbia Center, in 1985. He had wanted to go higher, but the FAA objected and Selig backed off. Four years later, Selig’s tower lost its coast crown to L.A.’s Library Tower, today known as the U.S. Bank Tower.

Unlike Selig, Crescent Heights thinks that being a possible impediment to air traffic from nearby Boeing Field, just south of downtown Seattle, is resolvable. Christina Disney, a Los Angeles spokeswoman for Crescent Heights, issued a statement calling the FAA challenge “a standard, business-as-usual review process which the FAA applies to all tall buildings in downtown Seattle.... Once complete, we anticipate that a determination of ‘no hazard’ will be reached.”

Crescent Heights, run by Miami billionaire Sonny Kahn, who once successfully sued Donald Trump over a partnership deal that went bad, is “on somewhat of a streak of high-rise residential proposals around the nation,” said Gabel of the Council on Tall Buildings, including a 39-story residential tower in Century City. The company says it plans to create “an iconic building” in Seattle “that redefines the skyline and changes the way we live, work and play downtown.” Think of it as “a vertical neighborhood.”

To critics, downsize matters more. Phallic and other symbols were mentioned by Seattle newspapers commenters and attendees at a public hearing when referring to the building’s height and design; one described it as “a long white middle finger sticking it to the city.”

But with design and construction techniques enabling higher builds, the market for skyscrapers is ripe, said Barr, the Rutgers economist.

“My research shows that condo buyers in New York City are willing to pay nearly 1% more for each floor up, on average — thus 25 stories higher can mean up to 25% more income. Office rent premiums, I find, rise around 0.6% per floor, or about 6% for every 10 floors higher. Furthermore, developers are increasing the ceiling heights in luxury condos because tall ceilings are in vogue — and new technology allows them to provide them more efficiently.”

The nation’s tallest building, One World Trade Center in New York, comes in at 1,776 feet. Is there a 2,000-plus foot skyscraper in America’s future? Barr doesn’t think so, citing government reluctance, land and labor costs, and zoning regulations. “In short,” he said, “the economic, political and social forces do not seem to exist in the U.S. to favor the 200-story building.” Not today, anyway.

Anderson is a special correspondent.

ALSO

How a Lincoln High teacher gets all his students to pass the AP Calculus exam

As Clinton seeks to break the glass ceiling, many young feminists shrug

L.A. County man wants judge to declare him winner of $63-million Lotto jackpot

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.