Q&A: Trump and the Goldwater Rule: When is it OK to voice a professional opinion about the mental health of the president?

The American Psychiatric Assn. years ago adopted the Goldwater Rule. (June 19, 2017)

- Share via

Since

Some in the professional psychiatric community have been moved to join in, offering their own expert analysis on why the president says what he says and does what he does.

But should they? Not according to the American Psychiatric Assn., which years ago adopted a rule for its 37,000 licensed members against offering a public opinion about the mental health or general psychological makeup of a public figure.

It’s known as the Goldwater Rule, and in the era of President Trump, it’s suddenly the subject of vigorous discussion — most recently at a meeting of the American Psychiatric Assn. last month in San Diego.

So what exactly is the Goldwater Rule?

Here are some details:

What is the Goldwater Rule?

It’s officially known as Section 7.3 of the American Psychiatric Assn.’s code of ethics.

This is how the organization’s ethics committee defines it: “On occasion psychiatrists are asked for an opinion about an individual who is in the light of public attention or who has disclosed information about himself/herself through public media. In such circumstances, a psychiatrist may share with the public his or her expertise about psychiatric issues in general. However, it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”

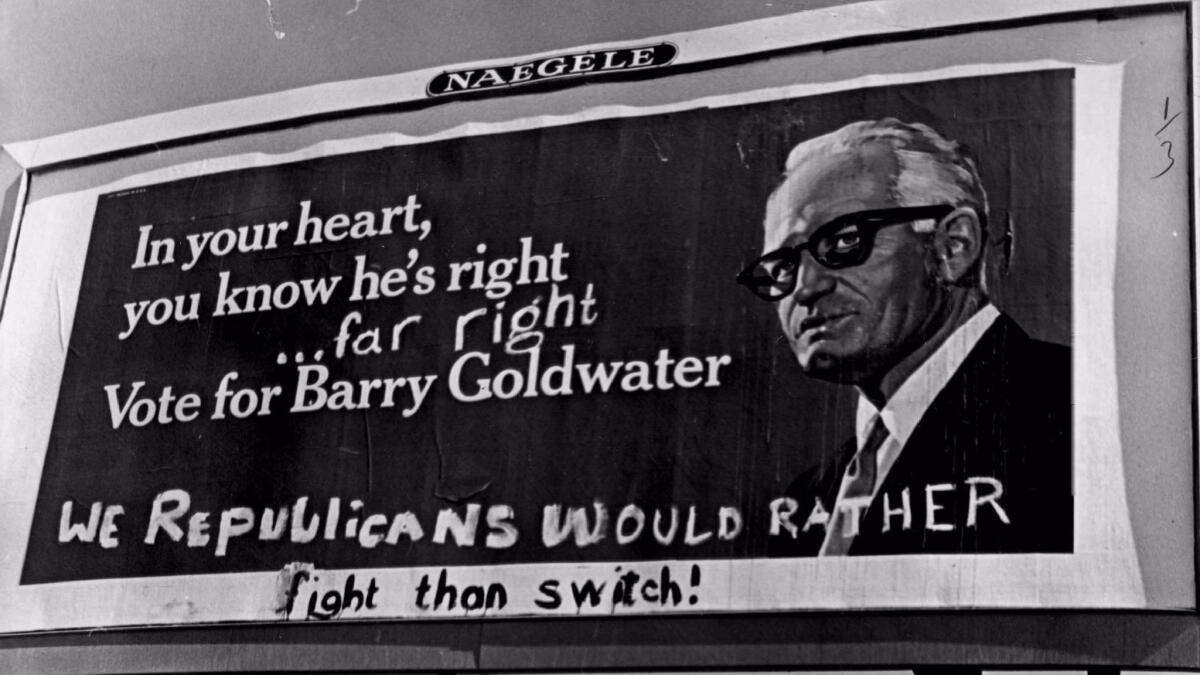

So why is it called the Goldwater Rule?

The rule dates back to an incident during the 1964 election between Democratic President

In September 1964, Fact Magazine, which is now defunct, published “The Unconscious of a Conservative: A Special Issue on the Mind of Barry Goldwater.” The magazine queried about 12,300 psychiatrists on whether Goldwater was psychologically fit to be president. Only about 2,400 psychiatrists responded to the magazine’s request, and of those about 1,200 said Goldwater was unfit for the job.

In 1966, two years after being trounced in the election, the Arizona senator sued the magazine for libel, and a federal jury awarded him $75,000 in punitive damages. Four years later, the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of the case.

Although the American Psychiatric Assn. had no direct involvement in the case, some viewed it as a blemish on psychiatry. So in 1973, the new rule was adopted by the group’s ethics board. Members who break it could be kicked out of the organization but do not lose their medical licenses.

So there’s been talk about reevaluating the rule?

Indeed.

In the decades after the rule went into effect, little debate took place over its merits. Then came the

As Trump and his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton, battled in a vitriolic campaign, some members of the American Psychiatric Assn. broke the rule and voiced concerns about what they described as Trump’s erratic and impulsive behavior. They said it would be a disservice to the public to not speak out.

Maria A. Oquendo, then-president of the association, responded with an open letter to members in August.

“We live in an age where information on a given individual is easier to access and more abundant than ever before, particularly if that person happens to be a public figure,” she wrote. “With that in mind, I can understand the desire to get inside the mind of a presidential candidate.”

But she argued that if psychiatrists are allowed to make diagnoses without seeing a patient, the public could lose confidence in the field and mental health patients could “feel stigmatized” by their own diagnoses and less inclined to seek help.

“Simply put, breaking the Goldwater Rule is irresponsible, potentially stigmatizing, and definitely unethical,” she wrote.

Did Trump’s victory elevate discourse on the issue?

Yes. Shortly after Trump entered the White House more than two dozen prominent psychiatrists wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times expressing discontent with the Goldwater Rule.

“Silence from the country’s mental health organizations has been due to a self-imposed dictum about evaluating public figures (the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 Goldwater Rule),” they wrote. “But this silence has resulted in a failure to lend our expertise to worried journalists and members of Congress at this critical time. We fear that too much is at stake to be silent any longer.”

How did the American Psychiatric Assn. react to the letter?

It strongly pushed back.

In a March statement, the organization reaffirmed its support for the Goldwater Rule.

“It was unethical and irresponsible back in 1964 to offer professional opinions on people who were not properly evaluated and it is unethical and irresponsible today,” Oquendo said in March. “In the past year, we have received numerous inquiries from member psychiatrists, the press and the public about the Goldwater Rule. We decided to clarify the ethical underpinnings of the principle and answer some of the common questions raised by our members. APA continues to support these ethical principles.”

During a recent interview, Dr. Rebecca Weintraub Brendel, a consultant to the association’s ethics committee, said a “physician can’t arrive at a diagnosis without an examination that considers underlying causes of an individual’s behavior, including medical conditions.”

“For example, someone with diabetes could act erratically or confused because their blood sugar levels need to be adjusted,” Brendel said. “Also, publicly discussing someone’s mental state without an examination is potentially stigmatizing for those with mental illness and could lead them to avoid treatment for fear of having their condition publicly discussed or out of concern about the methods of diagnosis.”

What about the dissenters?

“It’s a silly rule,” said Lance Dodes, a Los Angeles-based psychiatrist and retired clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, who was among those to sign the letter. “The APA is not protecting Donald Trump; they’re protecting themselves.”

Dodes, a former member of the association, believes Trump’s presidency could hurt national security.

“He has an antisocial personality disorder,” Dodes said. “This is not difficult to diagnose.… It’s clear to see.”

John Zinner, a clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at George Washington University, says many Americans are scared and concerned about Trump’s behavior and that his field has a responsibility to speak out.

“People are afraid he could create havoc due to his impulsiveness,” Zinner said.

So where do things stand now?

The rule remains in place.

In May, at its annual meeting in San Diego, the association held a panel discussion weighing the pros and cons of the rule.

Ultimately it was an effort to create a public discourse around the issue.

Ellen Covey, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington, says it is appropriate for mental health professionals to “condemn specific patterns of behavior such as habitual lying, blatant disrespect for others, self-contradiction and erratic behavior as inappropriate for a person holding a public office.”

But that’s different than making a diagnosis, she said.

“Such behavior patterns can be pointed out without the need to label them as a specific psychopathology,” she said. “The behavior speaks for itself.”

Twitter: @kurtisalee

ALSO

Demand for UC immigrant student legal services soars as Trump policies sow uncertainty

Young American women are poorer than their moms and grandmas, and more likely to commit suicide

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.