If you can stomach only one COVID closure novel, make it Michael Cunningham’s ‘Day’

- Share via

Review

Day

By Michael Cunningham

Random House: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

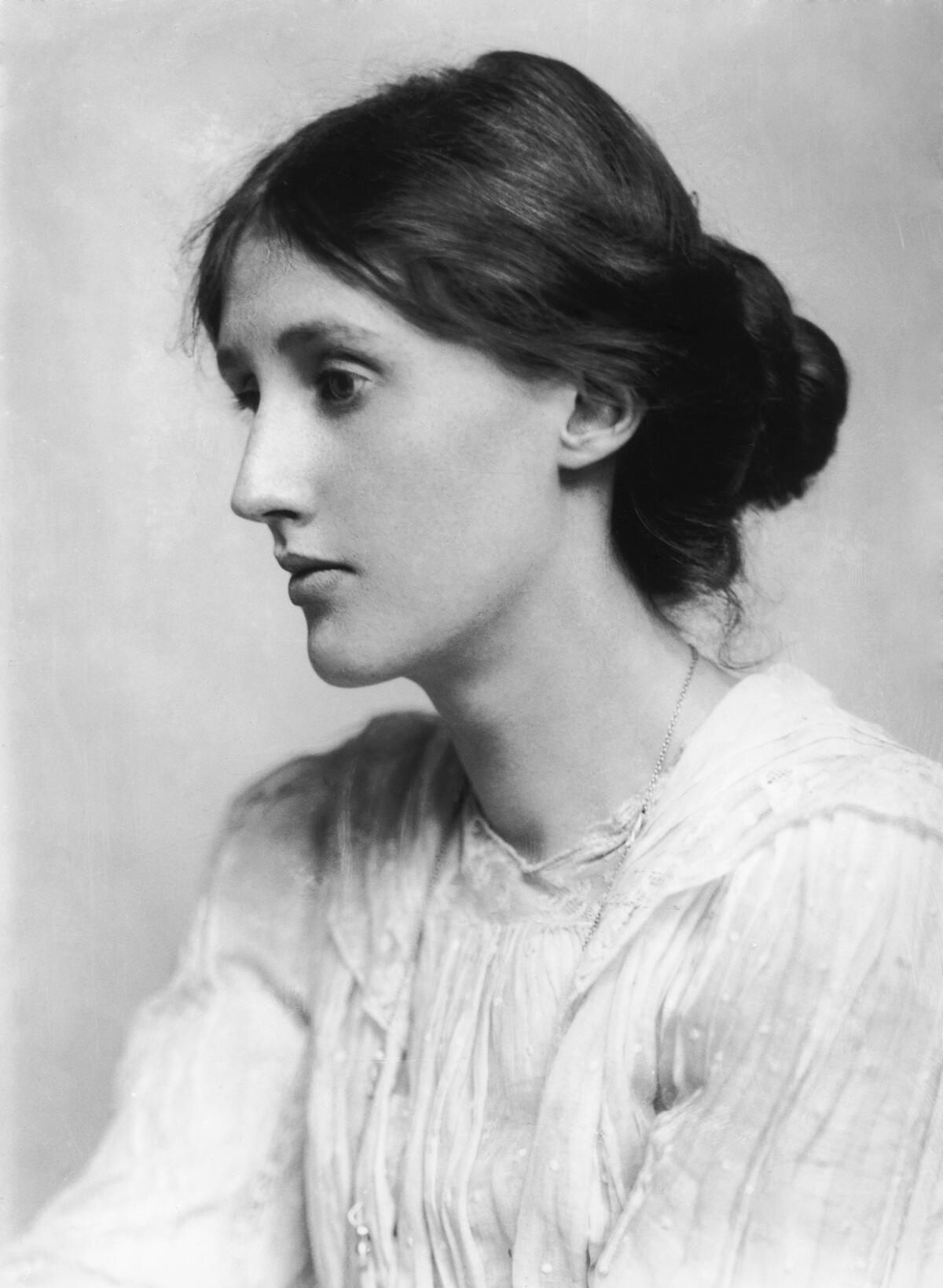

Michael Cunningham is possessed by a spirit, one whom a good deal of contemporary writers find it hard to shake: Virginia Woolf walks the hallways of his novels. Her motifs pop their heads in, his characters share names with hers, and his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1998 novel “The Hours” revives Woolf herself as a protagonist.

Of course, Woolf stands as a foundational pillar for contemporary literature, and her influence knows no bounds. (In her new novel “My Work,” Danish author Olga Ravn relays “the impression that any art made by a woman except Virginia Woolf was a secret.”) But in “Day,” his first new novel in 10 years, Cunningham resurrects the long-dead English novelist in the unlikely form of an aspiring Instagram influencer called Wolfe, who is in fact the fictional creation of depressed 30-something Brooklyner named Robbie. Virginia Woolf, GRWM?

Like “The Hours,” this novel is divided into three acts. “Day” takes place on the morning of April 5, 2019; the afternoon of April 5, 2020; and the evening of April 5, 2021. Pre-pandemic, early pandemic, later pandemic. Although COVID-19 is never mentioned by name, Cunningham pressed his point in an interview earlier this year. “How does anybody,” he asked, “write a contemporary novel that’s about human beings that’s not about the pandemic?”

The reigning poet of Twitter, also a memoirist, aims to capture the emptiness of social media, and then transcend it, in “No One Is Talking About This.”

But with new emergencies rushing by us each day, I find it harder and harder to abide literature concerned with the pandemic itself, rather than its long-tail outcomes. (Woolf’s own “Mrs. Dalloway” — an obvious influence on “Day” — benefited from being set after, not during, the flu epidemic of 1919-20.)

And yet, “Day” is not really about the pandemic at all, and its first section, set long before anyone besides virologists had ever uttered the word “coronavirus,” is by far its strongest. Cunningham scatters his characters to their separate emotional exiles with an aim to bring them together at day’s (and ”Day‘s”) end. Dispersal is his forte.

Robbie and Isabel Walker are a brother and sister living on the cusp of great change. Robbie deferred medical school a decade earlier and teaches sixth grade, living in the leaky attic room above the “starter apartment” Isabel and her family have occupied far longer than expected. Robbie is, ostensibly, planning to move out so Isabel’s preteen son can have a room of his own; his apartment search is the typical dismal and humbling New York experience, and both siblings waver on whether he should go.

Meanwhile, Isabel wonders how long she can march toward irrelevance as a magazine editor; her husband, Dan, a former C-list rocker who “looked, at age twenty, like a seraph out of Botticelli,” now cooks up pancakes for the kids rather than hit songs; and their 5-year-old daughter Violet “is coming into a world of hidden rules, which she can learn only by breaking them.”

I always hate these sorts of plot summaries in reviews — a bunch of characters caught up in trivial-sounding minutiae: Who cares? But Cunningham beautifully pries apart the notion of what it means to have outgrown something, to be living in the liminal space between an earlier self and a future self, to be unable “to reenter the orderly passage of time.” “Day” is even set on a date New Yorkers will recognize as a kind of faux spring, when, in defiance of the calendar, the earth stays hard and the flowers huddle underground.

As editor and annotator of this new edition, Merve Emre leads the reader to a new understanding of ‘Mrs. Dalloway.’

Cunningham’s big project has always revolved around examining time’s fitfulness. Like Henry James in “What Maisie Knew” — the 1897 divorce novella written from the point of view of the child — Cunningham understands that the tipping points of childhood are ripe moments for examination. As Violet ages — from 5 to 6 to 7 in one protracted day — she starts to take on an interior life her parents can’t access or even see. She’s aware that she is growing up and that doing so requires a kind of manufactured innocence put on for her parents’ sake. “At what age do children begin to realize,” Cunningham asks, “that they’re expected, sometimes, to be parodies of children?”

The comparison to James would probably feel apt for Cunningham. He is always in conversation with his forebears and contemporaries, mindful that literature is a giant web and his own work has a long ancestry and living relatives.

In “Day,” two characters take a road trip to visit “the world’s second-largest ball of twine,” an inane, ironic tourist spot that heavily hints at “the most photographed barn in America” in Don DeLillo’s “White Noise.” There are other nods to George Eliot, Colm Toíbín, Shakespeare’s tragedies. One character teaches university literature, and as her class discusses Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth,” she reminds everyone that the 1905 novel is “more or less the end of the marriage story.” Then she asks if they’ve “read the Vivian Gornick,” meaning the critic’s essay “The End of the Novel of Love,” which demoted the love story from its central place in literature.

But in this novel that puzzles over the elasticity of all kinds of love — familial, parental, erotic, queer, fraternal, ambiguous — I yearned for Cunningham to forget his literary peers and stick with his own special talent for proving Gornick wrong. Yes, the traditional “marriage story” no longer works, but Cunningham is a writer who understands the flexibility and freedom that comes after that kind of narrative collapse.

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

Until its end, when the novel loses its way by killing off a character (Woolf’s calculation: “someone must die in order that others value life more”), “Day” is at its contemplative best when it shakes off influence and oversight. Robbie and Isabel, siblings who love each other the way a drowning man loves his life jacket, are no “small good thing,” as Gornick might have called them. They are the biggest thing, the only thing. And when Cunningham writes like himself, and not like an apostle, he is one of love’s greatest witnesses.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.