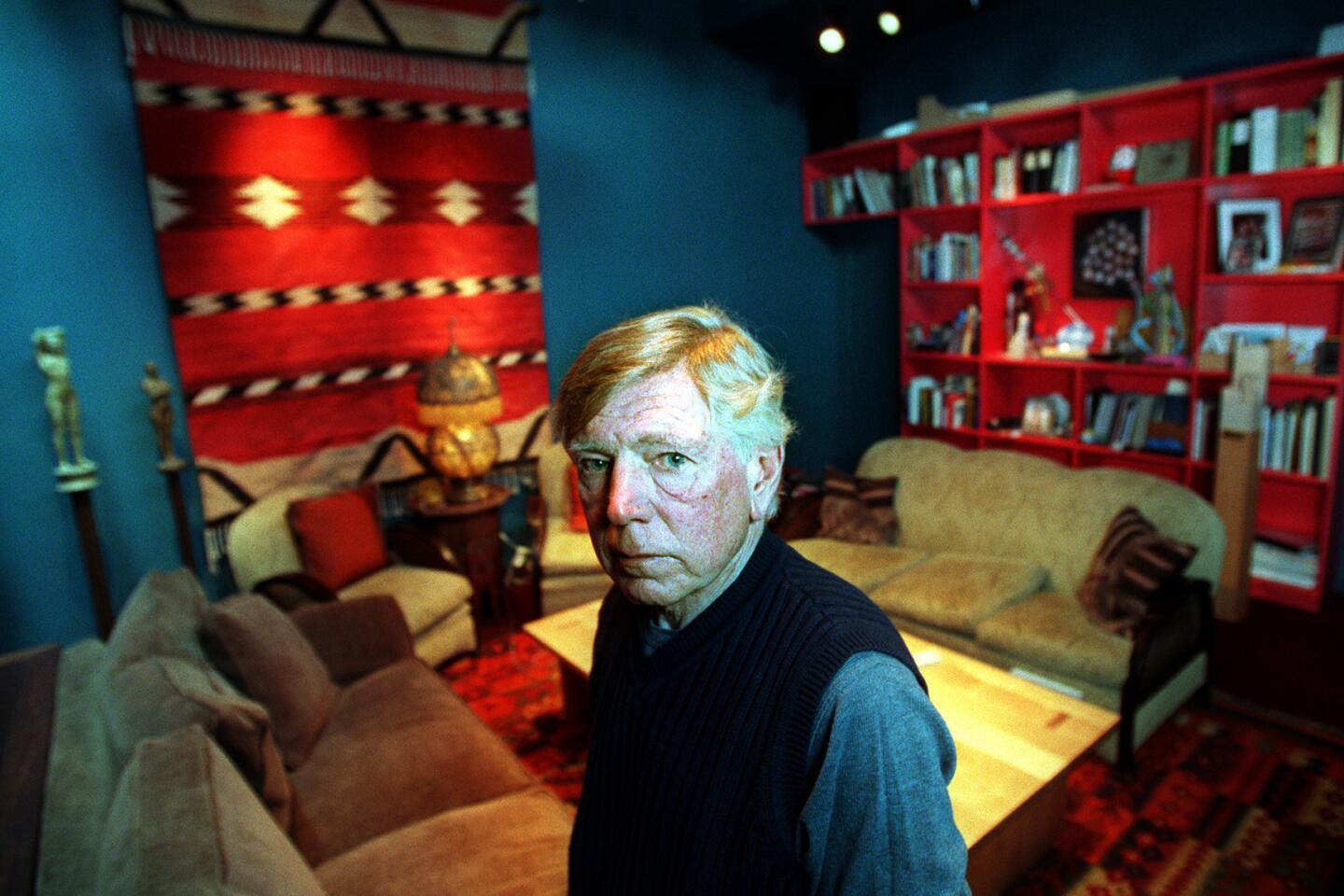

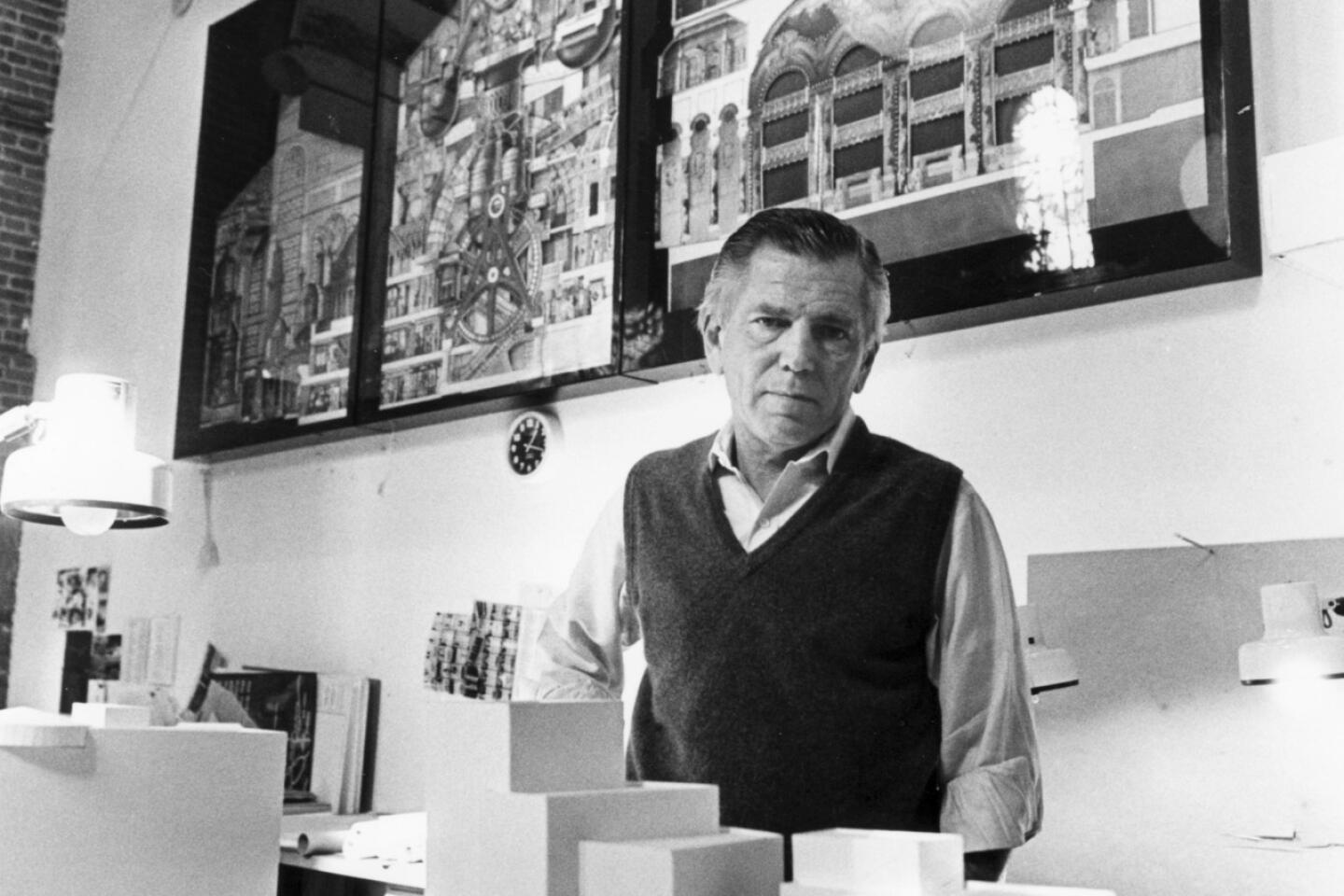

Jon Jerde dies at 75; L.A. architect redefined shopping mall, urban spaces

- Share via

Architect Jon Jerde spent 10 years of his career designing standard, suburban shopping malls. Which he grew to hate.

When he got a chance to bust out of the basic box, he came up with multi-level, multi-building malls to which he added bridges, arches, winding pathways, vast patios, towers, digitally controlled fountains and huge multi-media screens.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Jon Jerde: The obituary of architect Jon Jerde in the Feb. 10 California section misspelled the name Nicolais as Nicholais in the architecture firm of Burke, Kober, Nicolais and Archuleta. —

------------

Jerde’s “experience” malls and related projects — including Universal CityWalk, Horton Plaza in San Diego, the Mall of America outside Minneapolis, and the Bellagio hotel complex and Fremont Street Experience in Las Vegas — are his reimagining of the classic town square.

“He blew open the shopping mall and transformed it into a lively urban environment which attracts people, lots of people,” Richard Weinstein, the former dean of UCLA’s school architecture and urban planning, once said.

Jerde, 75, who also helped oversee the design of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, died Monday at his home in Brentwood, according to an announcement from his wife, architect Janice Ambry Jerde. He had cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

He had been absent since 2013 from his firm Jerde Partnership — headquartered off Venice Beach, with branch offices in Shanghai, Hong Kong and Seoul.

In 1963, the Los Angeles Times ran an article headlined “USC’s Jon Jerde Wins Architectural Fellowship.” The student, who had grown up in remote areas of the country as his father traveled to oil rig jobs, had won a $3,500 award to travel and study in Europe.

The trip changed his life.

“Europe was a revelation,” he said in a 1988 Times interview, with people from all walks of life going to city centers to “stroll aimlessly” and “gather, mingle and interact.”

He aimed to re-create that in the United States, where many downtowns had fallen on hard times. But at his first major job after graduation — at the L.A. firm of Burke, Kober, Nicholais, Archuleta — he designed malls for suburbs. He needed the work, but complained that no one would let him try his blow-up-the-box ideas.

In 1977, prominent mall developer Ernie Hahn called his bluff — he hired Jerde to design a mall for a dilapidated area of downtown San Diego.

Jerde, who went out on his own, came up with a multi-level mall that he likened to several acts of a play. “It was high variety, so people would be enchanted by moving through this place,” he said in the Times interview. “It had bridges and platforms and terraces and all sorts of things no one had ever seen before in these types of environments.”

Unlike architects who focus mostly on structures, Jerde made outdoor walking and gathering areas a high priority.

“Very quickly, it became clear that the big deal was the space between the buildings,” Jerde told the San Diego Union in 2005. “The openings are more important than the walls.”

It took eight years for the project to be completed.

In the meantime, Jerde was given the job of overseeing the look of the 1984 Games. Working in conjunction with color expert Deborah Sussman, they created temporary structures, signs, banners, gateways, flags, pylons and other items to give a unifying sense to widespread venues.

The abstract, colorful look, which Jerde described as “an invasion of butterflies,” drew wide praise. “If there was a special gold medal for creative ingenuity,” Time magazine wrote, “the U.S. Olympic design team should win it.”

Horton Plaza opened in 1985 to a public response far beyond hopeful estimates. Jerde said it would have been considered a success if it had gotten nine million visits in the first year, but it had more than 30 million.

It was a heady success for an architect who described himself as coming from “oil field trash.”

Jon Adams Jerde (pronounced JER-dee) was born Jan. 22, 1940 in Alton Ill., but was there only a short time before his family was on the move. It was an unsettled childhood, often spent in sparsely populated regions.

“My mother was an alcoholic. My father was usually away working,” he told The Times. “As a lonely kid, I collected trash items and built them into backyard constructions.”

He would create whole communities, complete with post offices and bars. “I guess I’m still doing it,” he said, “on a somewhat grander scale.”

He attributed his attraction to communal places to his isolated upbringing. “How we got into this in the first place,” he told the Sacramento Bee in 2002, “is I really love crowds.”

Because his father objected to his becoming an architect, he took courses at UCLA in engineering and art. A chance meeting in 1958 with a USC dean, who was impressed with Jerde’s building sketches, led to his getting financial aid to enroll in that school’s architecture program. He graduated in 1965.

In the wake of his success with the Olympic Games and Horton Plaza, he built his firm, which now has a staff of more than 100.

CityWalk opened in 1993 as part of Universal Studios’ entertainment complex. Like many of Jerde’s projects, it was built as an indoor/outdoor emporium designed for vigorous pedestrian traffic. Its L.A. theme featured styles as varied as Art Deco and futuristic.

Jerde described the $100-million project as “a movie set of quintessential L.A. Its theme is a kind of lively, stylish trash that’s very Angeleno.”

If it was trash, it was without the grit — the project was situated up a long ramp from a street in a tightly controlled space. Architecture critic Leon Whiteson, writing in The Times in 1993, said “CityWalk intends to create the feeling of being in a kind of archetypal L.A. dream street in which all the urban grime is edited out.”

Though some critics found it overly synthetic, Jerde’s firm said CityWalk has been a popular success and not just with tourists. About 67% of visitors to the site are locals, the firm says, racking up annual sales at about $800 per square foot.

About a third of the firm’s projects are in Asia. Of particular pride to Jerde was Canal City Hakata, located in Fukuoka, Japan. Opening in 1996, with a canal winding through, it had the architect back in his element: revitalizing a city center that had waned.

“It’s almost like having an old car you’d find in a barn that hasn’t been started for, you know, for decades,” he told CNN in 2000. “You figure out a way to reconstruct it, and turn the starter engine, and boom, it comes back to life.

“And you can take burned out cities and start them back up again, and it’s a very exciting and rewarding thing.”

Jerde was married four times. Besides Janice Ambry Jerde, he is survived by their son, Oliver; his children from his previous marriages, daughters Jennifer Jerde-Castor, Maggie Jerde-Joyce and Kate Jerde-Cole and son Christopher Jerde; and four grandchildren.

Los Angeles Times staff writer Elaine Woo contributed to this report.

Twitter: @davidcolker

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.