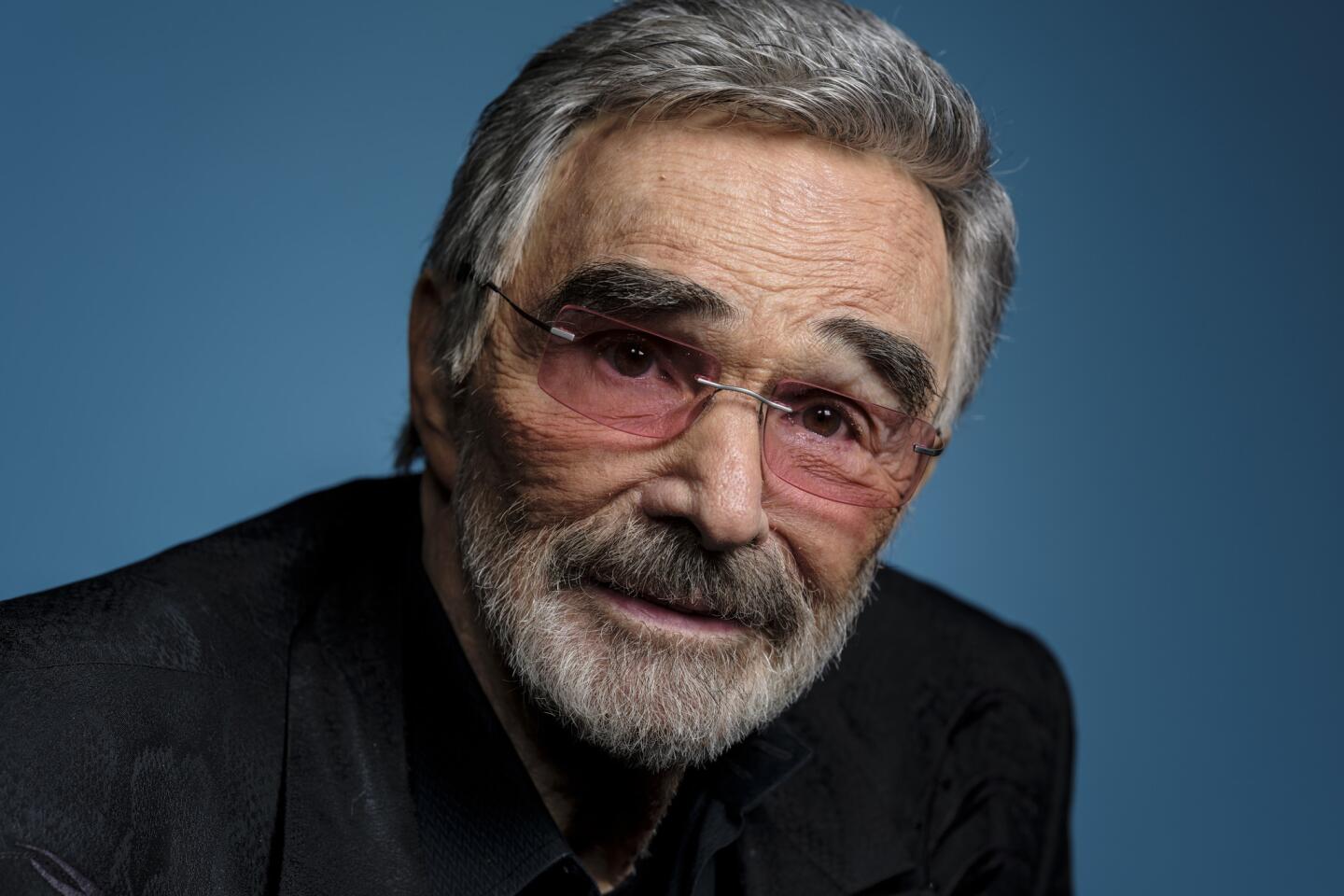

Burt Reynolds, wisecracking star of ‘Smokey and the Bandit’ and ‘Deliverance,’ dies at 82

- Share via

In the mid-1960s, Burt Reynolds had begun landing starring roles in films such as “Navajo Joe,” “100 Rifles,” “Sam Whiskey,” “Shark!,” “Impasse” and “Skullduggery.” They generally were the kind of movies that he joked “they show in prisons and airplanes because nobody can leave.”

That self-deprecating charm became his trademark and endeared him to the masses, turning him into Hollywood’s wisecracking, good-ol’ boy and a box-office champ in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

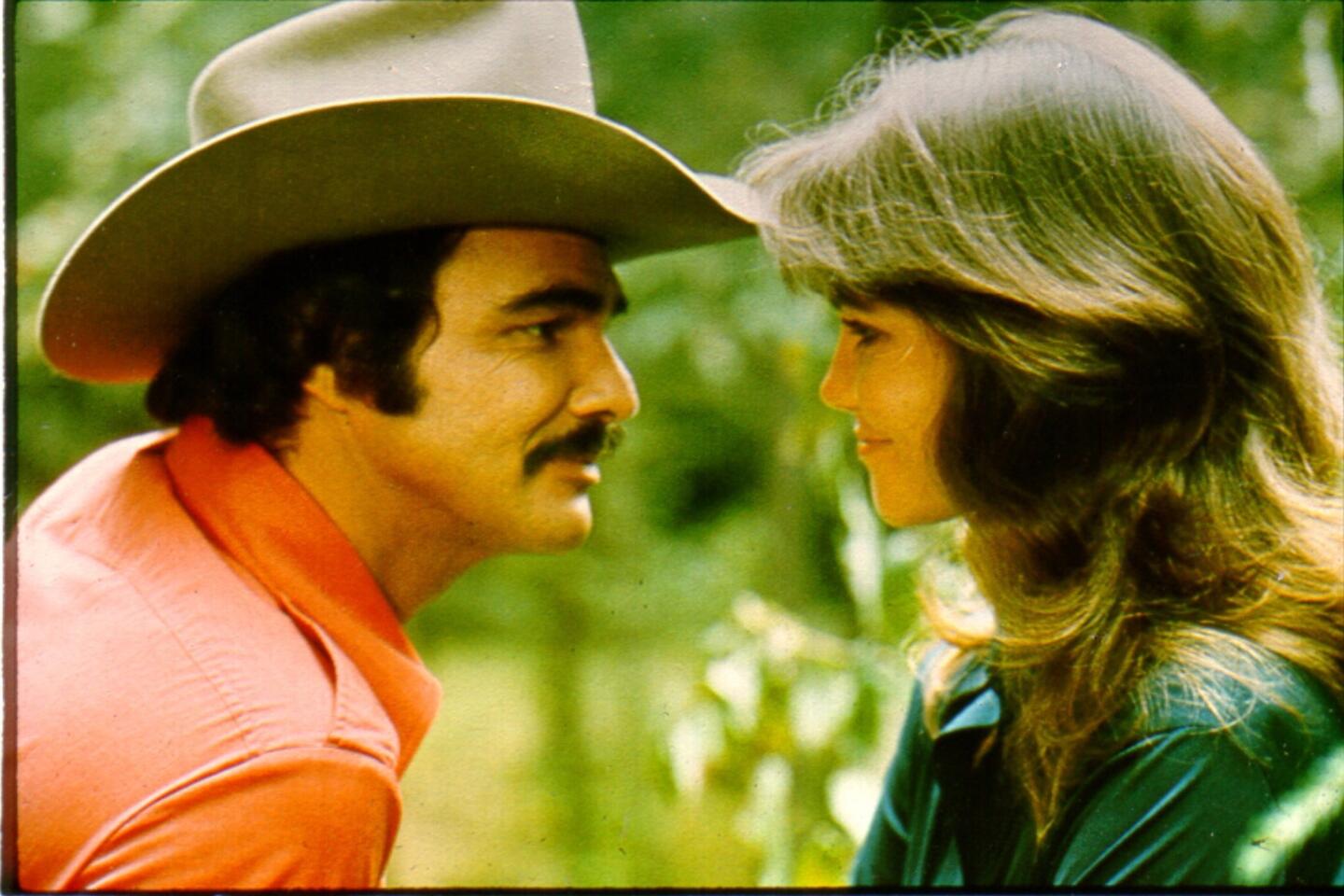

“He is the only movie star who didn’t come from a hit play or a big movie,” former girlfriend Sally Field, who starred with Reynolds in “Smokey and the Bandit” and three other movies, told Variety in 1997. “He just came crawling along, clutching and punching and digging his way.”

Burt Reynolds: Costars and admirers ‘mourn one of our favorite leading men’

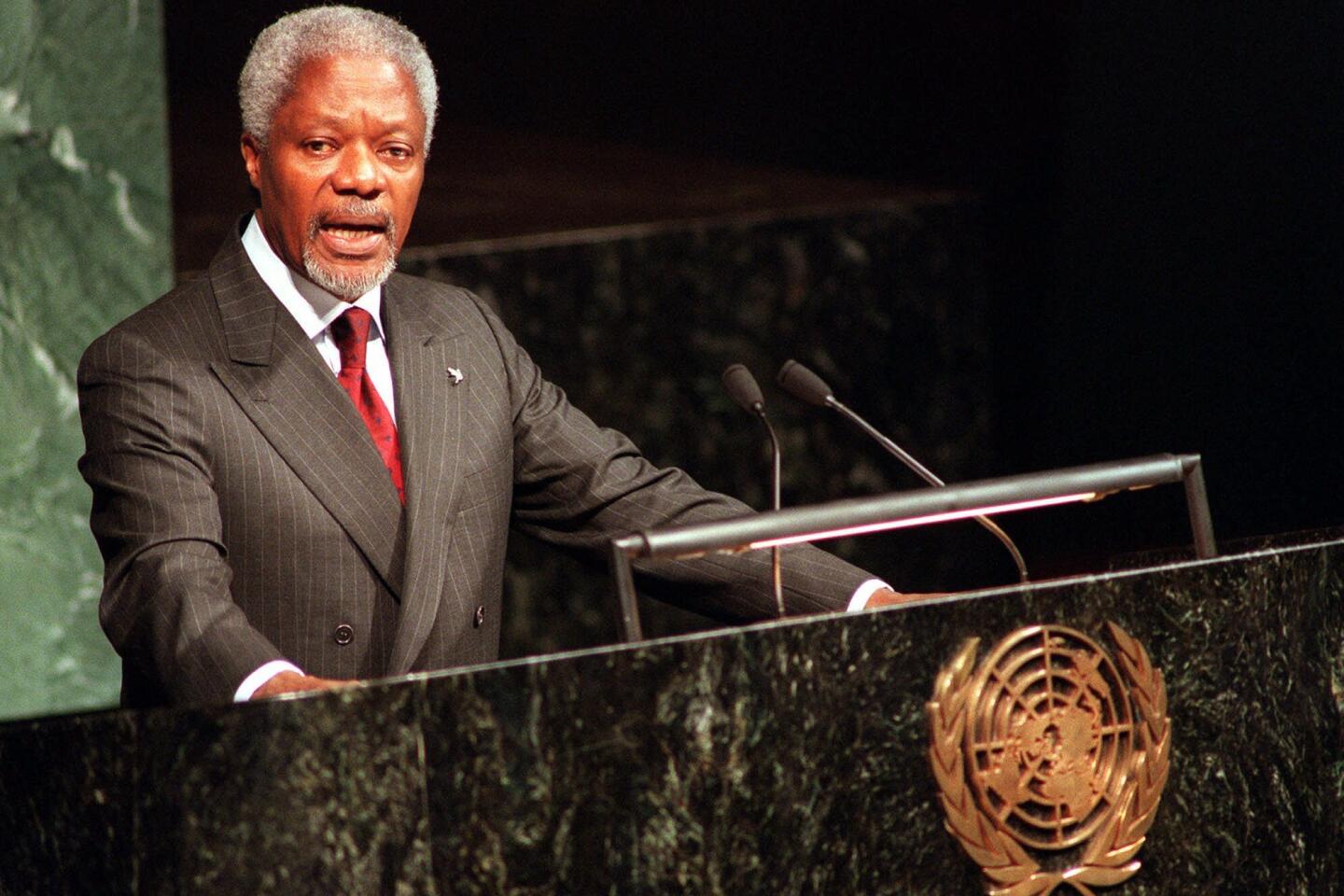

Reynolds, who also starred in “The Cannonball Run” and made pop-culture history as Cosmopolitan magazine’s first nude male centerfold, died Thursday in Jupiter, Fla., of cardiopulmonary arrest, according to his agent, Erik Kritzer. Reynolds was 82.

Field released a statement Thursday about her fond memories of Reynolds both on and off screen.

“There are times in your life that are so indelible, they never fade away. They stay alive, even 40 years later. My years with Burt never leave my mind,” Field said. “He will be in my history and my heart, for as long as I live. Rest, Buddy.”

“My uncle was not just a movie icon; he was a generous, passionate and sensitive man, who was dedicated to his family, friends, fans and acting students,” his niece Nancy Lee Hess said in a statement issued through Reynolds’ agent.

“He has had health issues, however, this was totally unexpected. He was tough. Anyone who breaks their tail bone on a river and finishes the movie is tough. And that’s who he was.”

For five years in a row — 1978 through 1982 — Reynolds was the No. 1 box-office star, in movies such as “Hooper,” “Starting Over,” “The End,” “Sharky’s Machine” and “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.”

Dolly Parton, Reynolds’ costar in 1982’s “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” expressed her grief through a statement: “Oh, how sad I am today along with Burt’s millions of fans around the world as we mourn one of our favorite leading men,” she said.

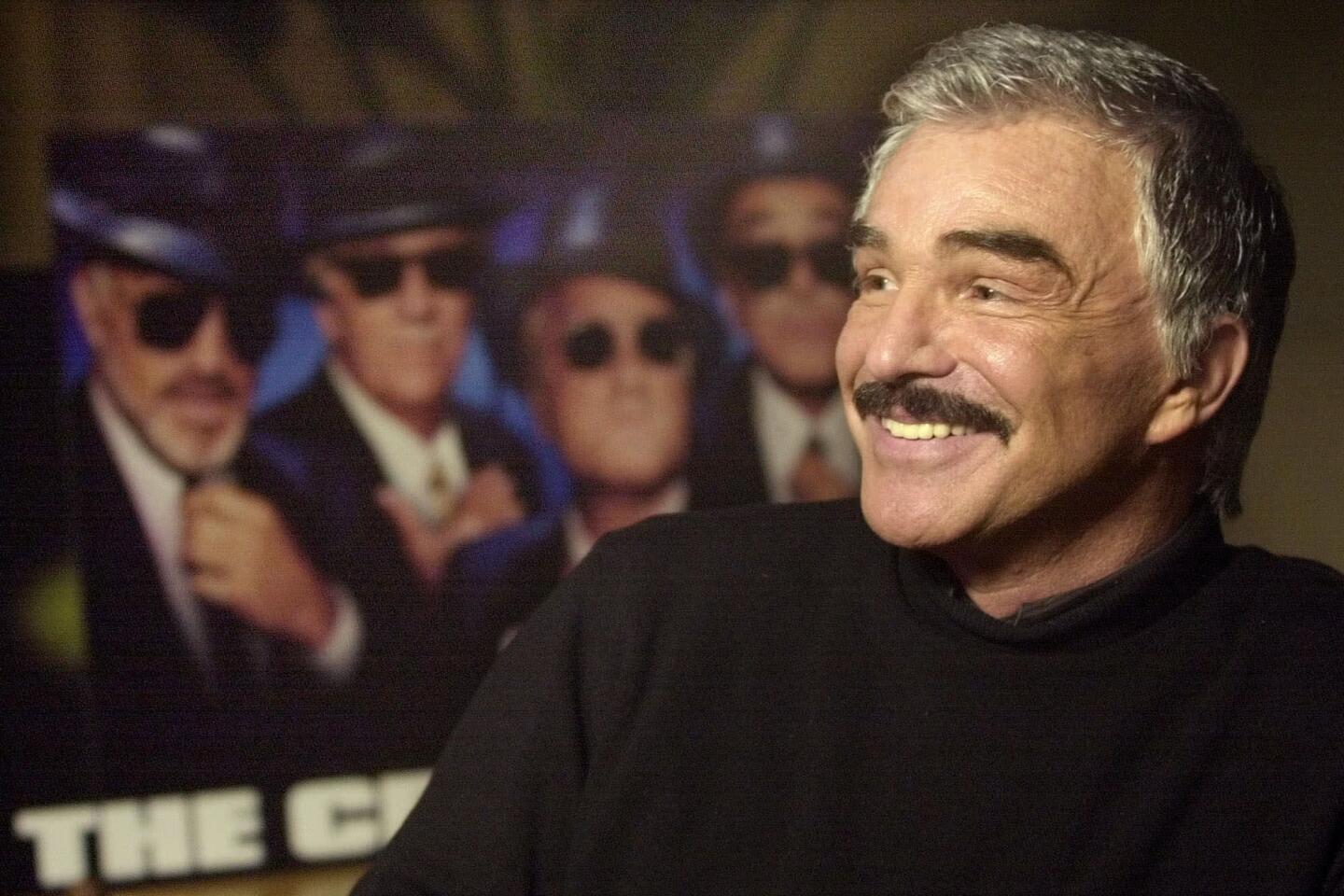

His more-than-50-year career was well known for its peaks and valleys, as Reynolds was the first to concede.

“My career is not like a regular chart. ... Mine looks like a heart attack,” he cracked in a 2001 interview with Canada’s Globe and Mail. “I counsel scores of young actors because they know I’ve stepped in just about every land mine along the way I could.”

Sally Field, plastic surgery and posing nude — Burt Reynolds discussed it all with The Times

Reynolds had been in Hollywood working in television and films for more than a decade before landing his breakout movie role in “Deliverance,” the 1972 drama directed by John Boorman about four men whose weekend canoe trip down a treacherous river in backwoods Georgia takes an unexpectedly dark turn.

As the macho leader of the group who proves deadly with a hunting bow, Reynolds gained widespread notice for his strong performance in the film, which was nominated for an Academy Award for best picture.

But by then, as Reynolds told The Times in 1972, he had decided to change his screen image “from standing around looking virile and mean” and instead “take the risks and be funny about it.”

And it’s the charming, lighter side of Reynolds, amply visible to the public during his frequent talk show appearances at the time, that turned him into a superstar.

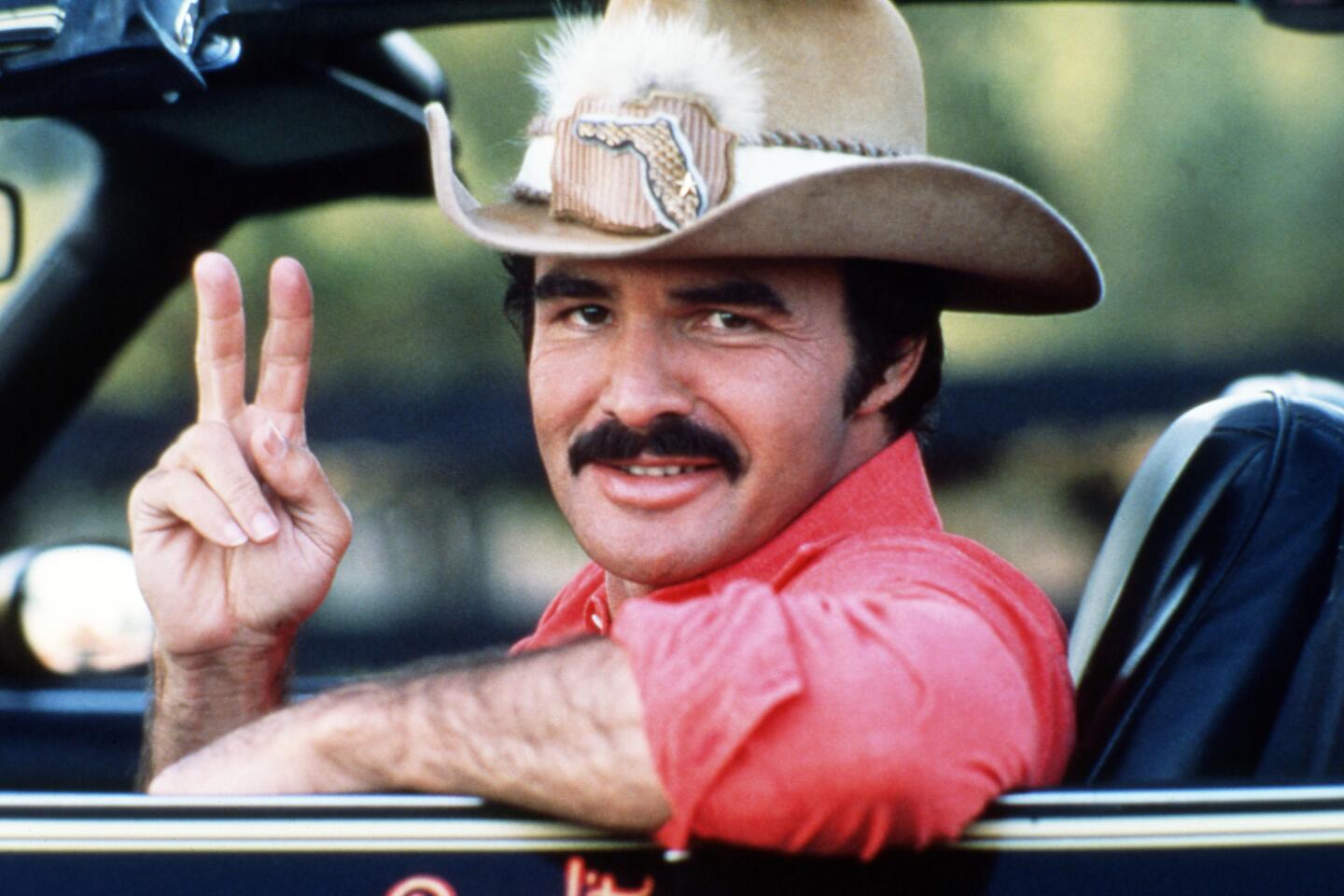

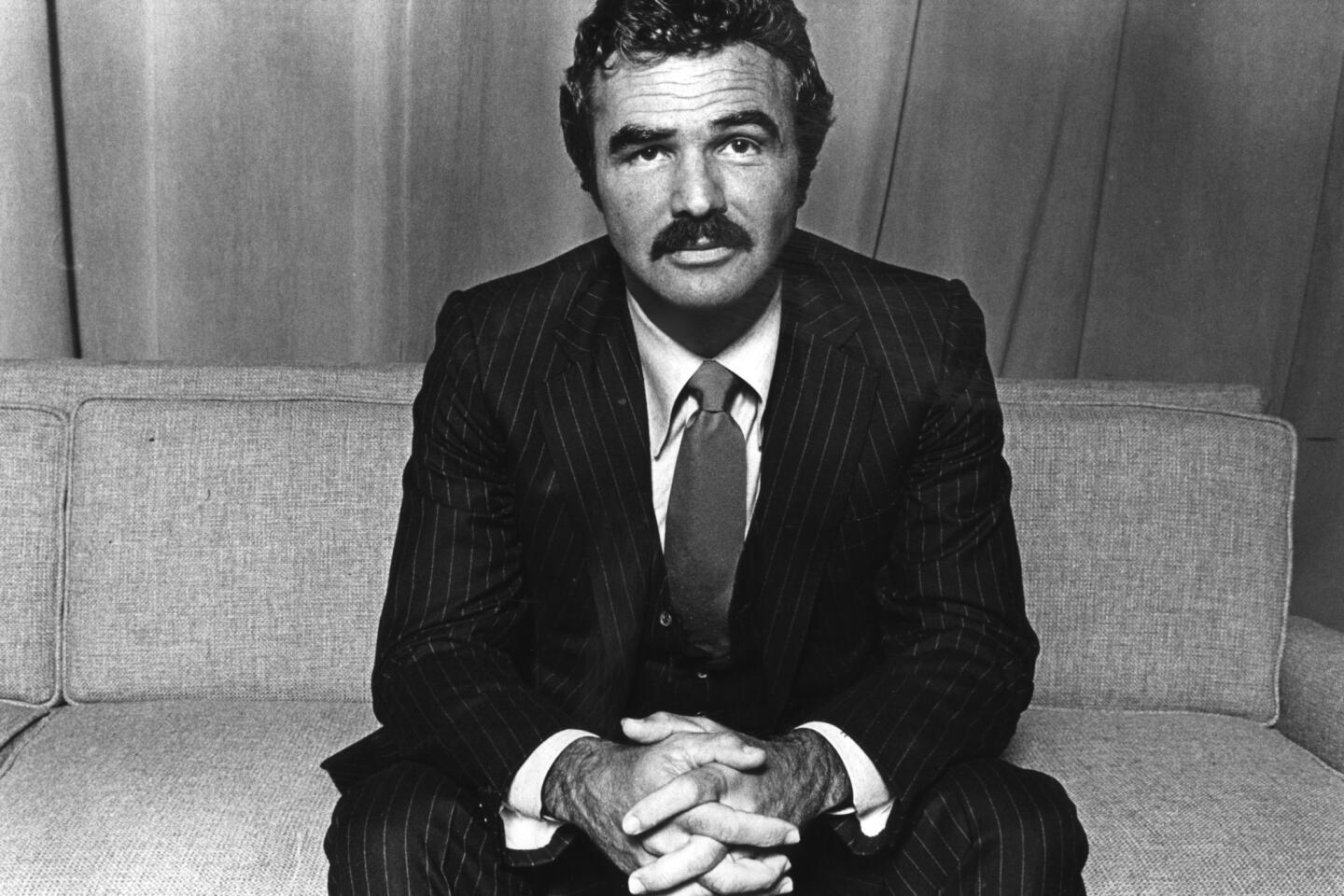

The dark-haired, ruggedly handsome actor, with his trademark mustache and distinctively infectious laugh, went on to star in a string of films, including “White Lightning,” “The Longest Yard,” “At Long Last Love,” “Lucky Lady,” “Hustle,” “Gator,” “Nickelodeon” and “Semi-Tough.”

“In most of his roles,” Playboy magazine observed in 1979, “he portrays a kind of macho pixy who often doesn’t take himself or even the film he’s in very seriously.”

An Appreciation: Burt Reynolds ran through my youth as a charmer and a spinner of wiles »

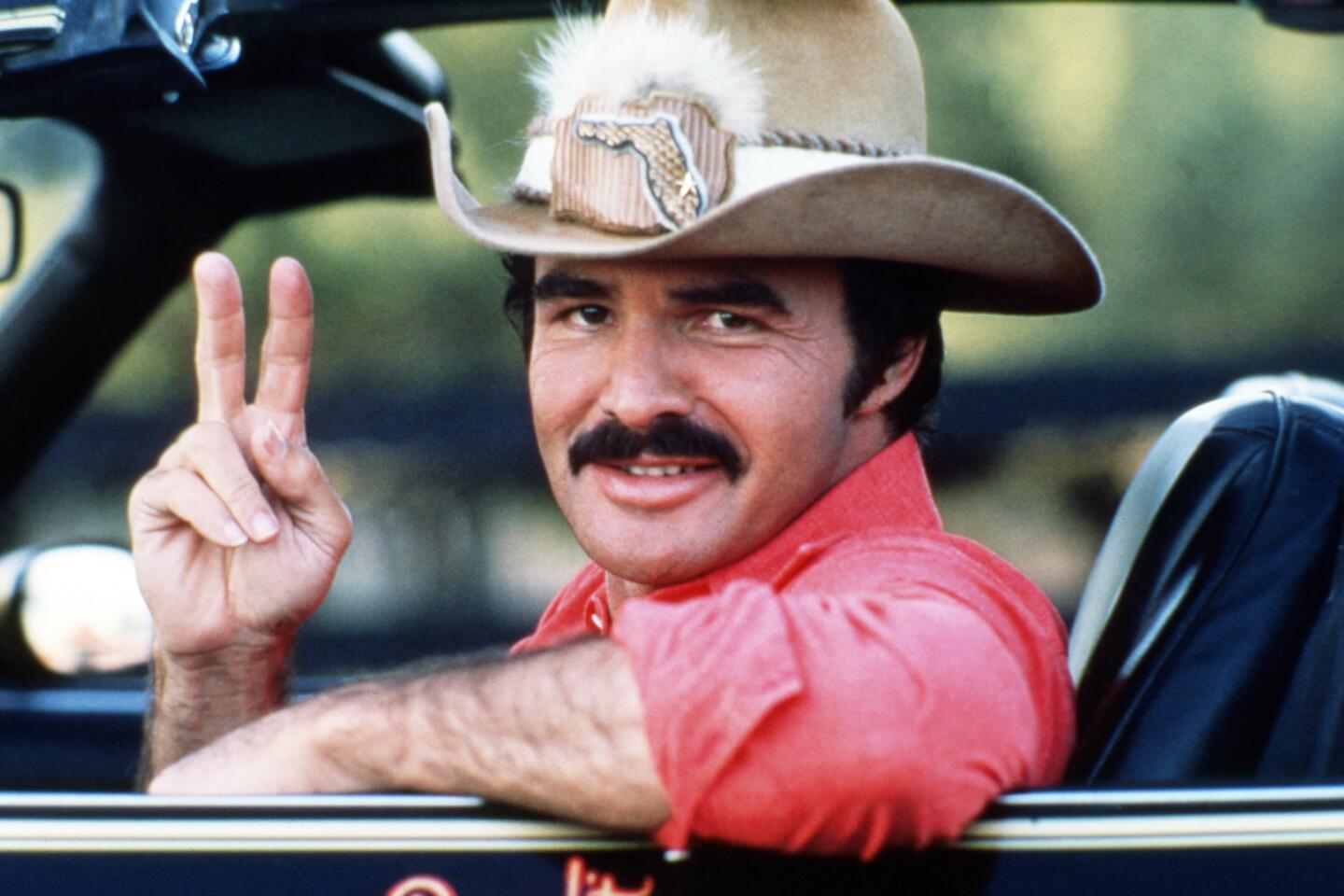

That most notably applied to his role in “Smokey and the Bandit,” the 1977 action comedy in which Reynolds, as the Coors beer-bootlegging Bandit opposite Jackie Gleason’s pursuing redneck sheriff, looks directly into the camera at one point and smiles at the audience.

Leonard Maltin’s “Movie Guide” says “Smokey and the Bandit” is “about as subtle as the Three Stooges.” But audiences found the black Trans Am-driving Reynolds’ car-chase movie irresistible, and it came in second only to “Star Wars” as the year’s top-grossing film.

“I’ve become the No. 1 box-office star in the world not because of the movies but in spite of them,” Reynolds told Playboy in 1979. “Critics told people they’d be fools to see the movies, but people went anyway.”

As for his attraction to moviegoers, he said, “I think it’s because I have the ability to make people happy and to have them say, ‘I like him.’ … I like to play this character who’s not quite all there, who steps down from his truck and scrapes the manure off his boots and who’s always fighting for his dignity. He’s anti-establishment, he’s funny and he’s somebody to cheer for — a hero.”

Reynolds was such a big star in the ’70s that even shaving off his mustache gained attention.

Minus his trademark facial hair, he acknowledged in a 1978 interview with the Washington Post, made him “look less sexy.”

“Now,” he joked, “I look like I make love in the bedroom and not on the living room floor.”

Burton Leon Reynolds Jr., who was one-quarter Cherokee on his father’s side, was born Feb. 11, 1936, at home in Lansing, Mich. A decade later, the family moved to Riviera Beach, Fla., where Burt Sr., a tough and strict World War II veteran, worked first as a general contractor and eventually became chief of police.

“I was completely rebellious, being the chief’s son,” Reynolds recalled in a 1992 interview with the Saturday Evening Post. “I was always in trouble.”

What saved him from himself, he said, was becoming a star athlete.

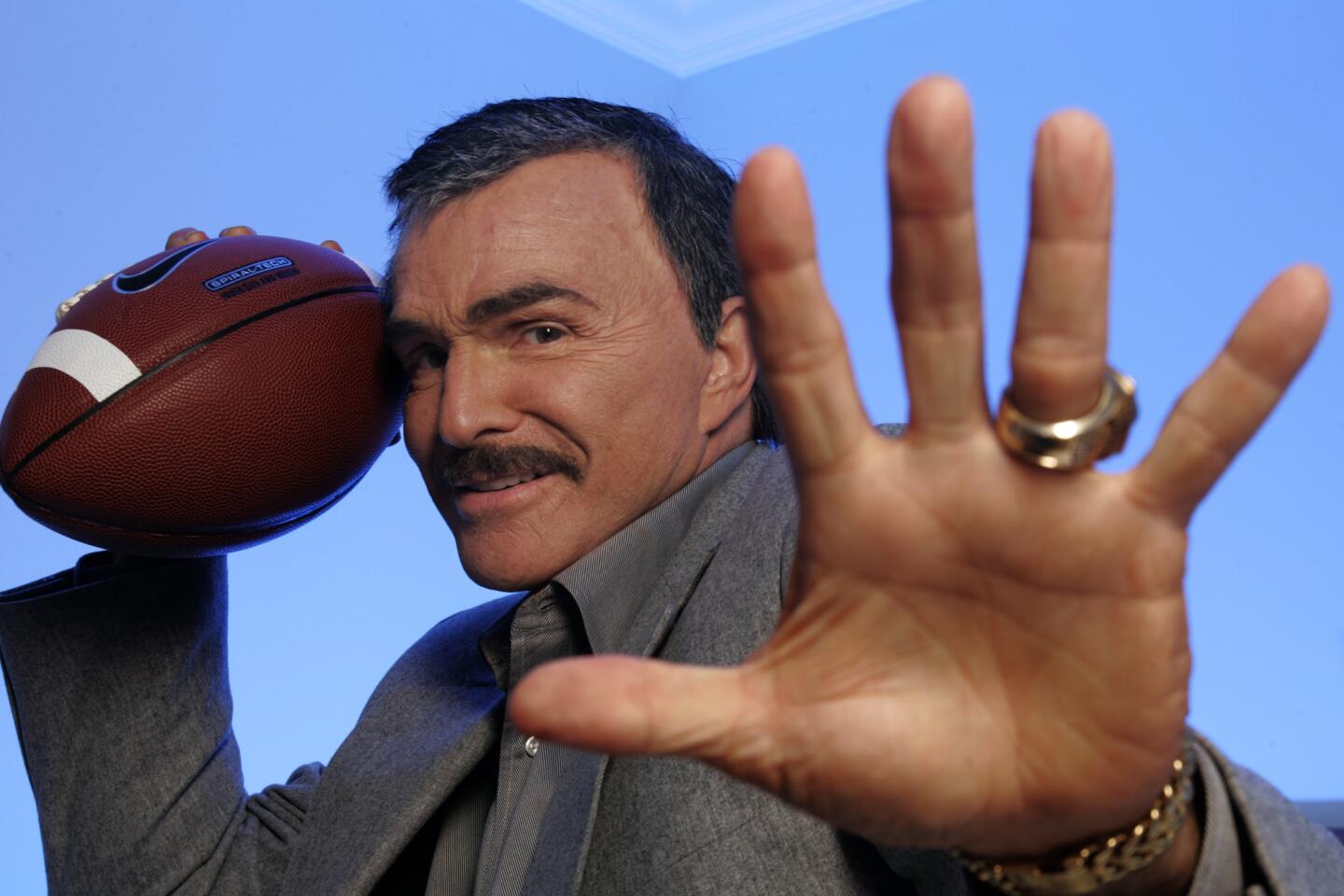

Known as a speedy fullback at Palm Beach High School, he earned a scholarship to Florida State University. But his dreams of playing professional football ended after he tore the cartilage in one of his knees during a game in 1955 and reinjured the knee in a near-fatal car accident later that year.

After recovering, Reynolds enrolled at what is now Palm Beach Community College where, at a professor’s urging, he auditioned for a production of “Outward Bound” and wound up winning the 1956 Florida State Drama Award.

Reynolds was a struggling young New York actor before becoming a contract player at Universal in 1958.

He had his first brush with fame co-starring with Darren McGavin in “Riverboat,” a 1959-61 TV adventure series. He went on to play the recurring role of half-Indian blacksmith Quint Asper in “Gunsmoke” from 1962 to 1965 before starring in two short-lived series of his own — the police dramas “Hawk” (1966) and “Dan August” (1970-71).

Burt Reynolds and Loni Anderson: The ugly divorce that just wouldn’t end »

Reynolds’ appearances on TV talk shows in the early ’70s, including numerous stints as a guest host on “The Tonight Show” in which he charmed viewers with his self-deprecating sense of humor, helped turn him into a national celebrity and paid unexpectedly big career dividends.

Indeed, it was after seeing Reynolds guest hosting “The Tonight Show” that director Boorman decided to cast him in “Deliverance.”

And a “Tonight Show” appearance with Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown prompted Brown to ask Reynolds to become the magazine’s first male nude centerfold.

“Why?” he asked her.

“Because,” she said, “you’re the only one who could do it with a twinkle in your eye.”

A major pop culture event, the April 1972 centerfold featured a grinning Reynolds with a cigarillo clenched between his teeth as he lay on a bearskin rug with one outstretched arm discreetly placed between his thighs.

The magazine issue featuring Reynolds, who said he had fortified himself for the photo shoot with belts of vodka, sold out immediately.

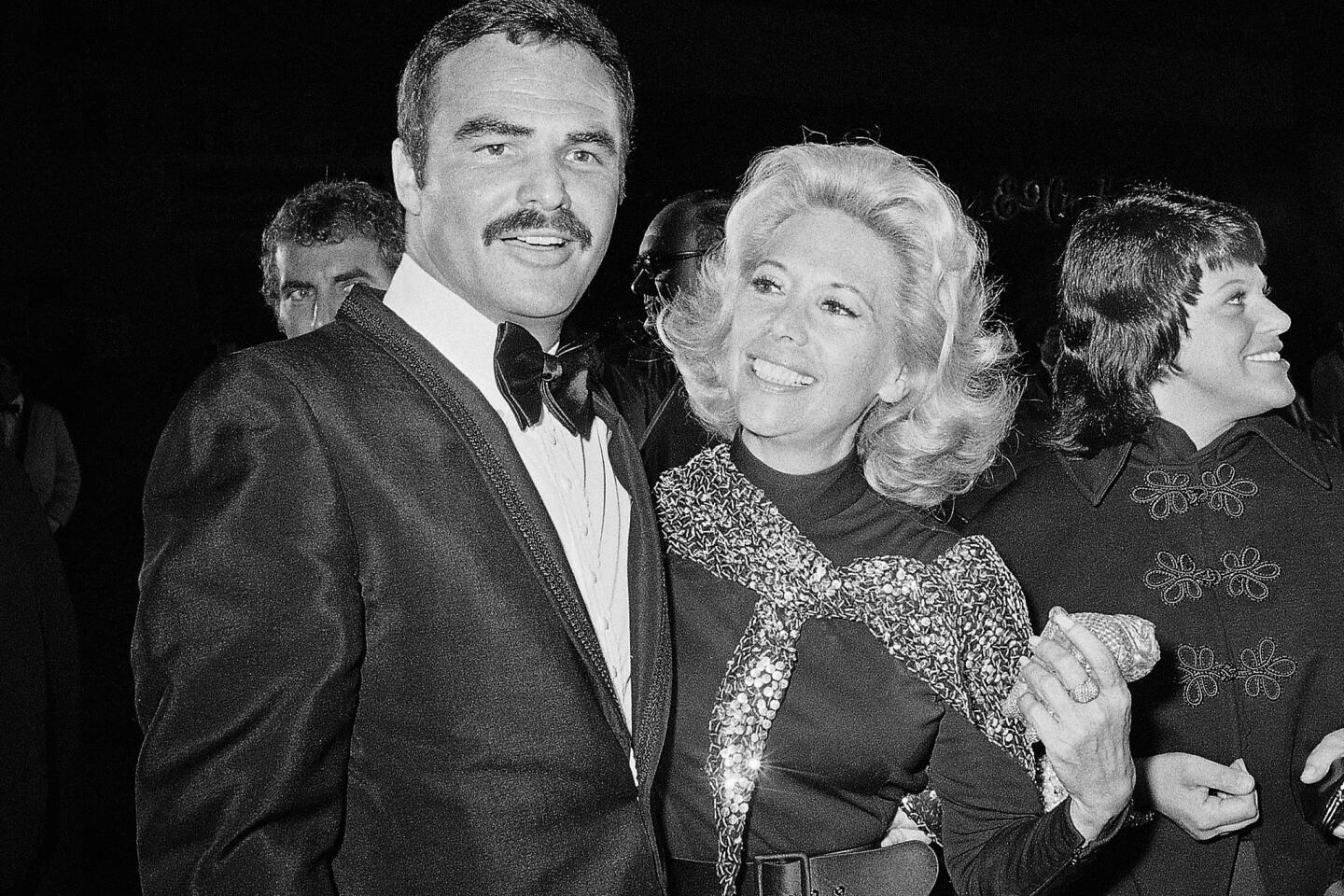

His pop-culture ubiquity, and a high-profile romance with singer Dinah Shore, who was 20 years his senior, put Reynolds on the show business map in high relief.

One downside was being swept up in rumors surrounding the drug overdose death of David Whiting, the manager of his co-star Sarah Miles, during filming of the 1973 western “The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing” on location in Arizona.

And while later dealing with the pain and other effects of having his jaw accidentally shattered during a fight scene while making “City Heat,” the 1984 comedy with Clint Eastwood, his resulting drastic weight loss spurred rumors that he had AIDS. In what he described as two years of his “own private hell,” he also had to overcome an addiction to the prescription sleep aid Halcion.

By then, Reynolds’ high-flying career was on a downswing thanks to a number of box office disappointments.

During the peak of his career in 1979, Reynolds opened the Burt Reynolds Dinner Theatre in Jupiter, Fla., where actors such as Martin Sheen, Carol Burnett and Julie Harris performed. He also launched the Burt Reynolds Institute for Theatre Training.

From the archives: Burt Reynolds is the comeback kid »

While continuing to make movies in the late 1980s, Reynolds returned to television — playing a Florida private detective in “B.L. Stryker,” which ran from 1989 to 1990 as part of the rotating “ABC Mystery Movie.”

He then starred as a small-town Arkansas high school football coach in “Evening Shade,” a 1990-94 CBS sitcom for which he won an Emmy in 1991 for outstanding lead actor in a comedy series.

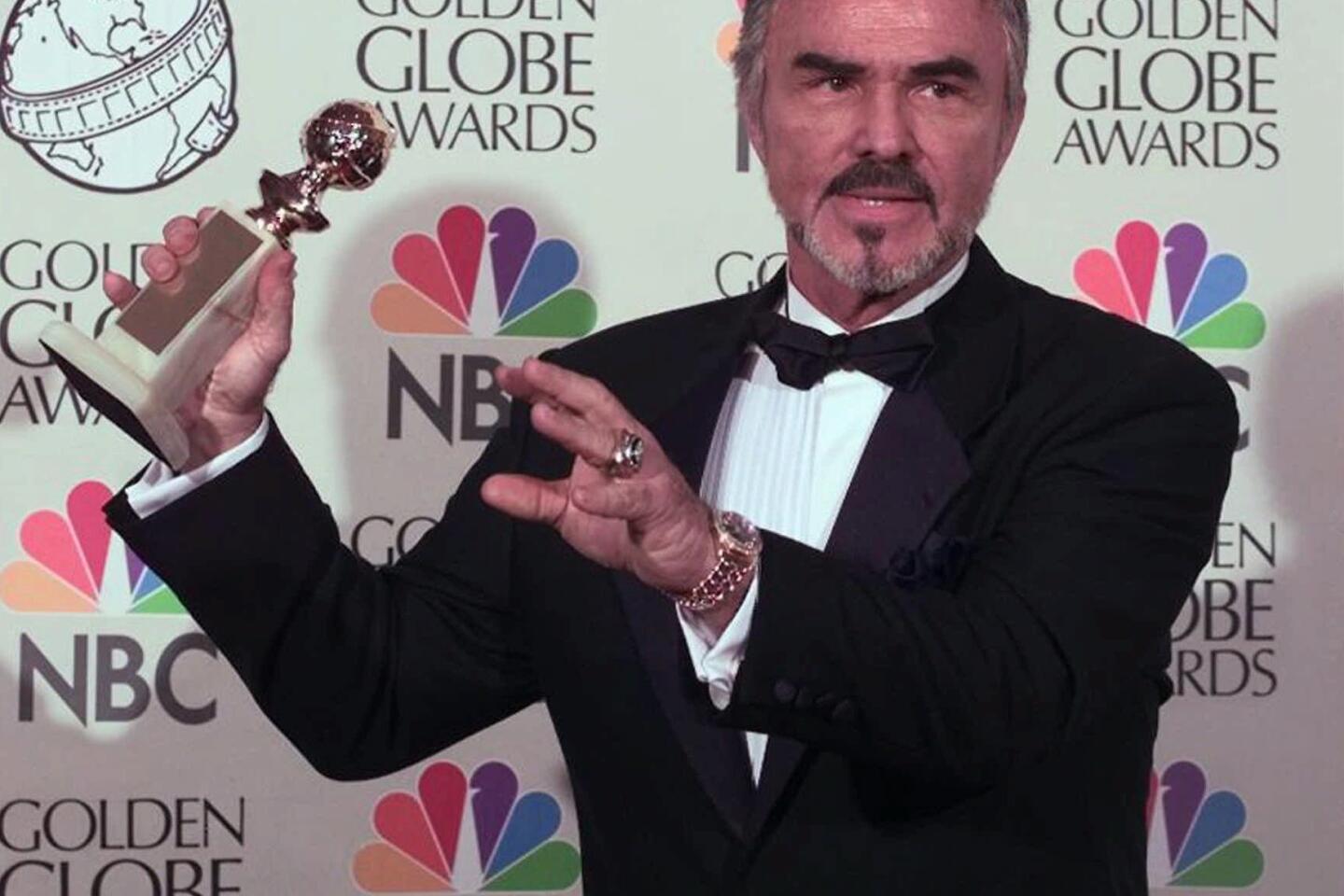

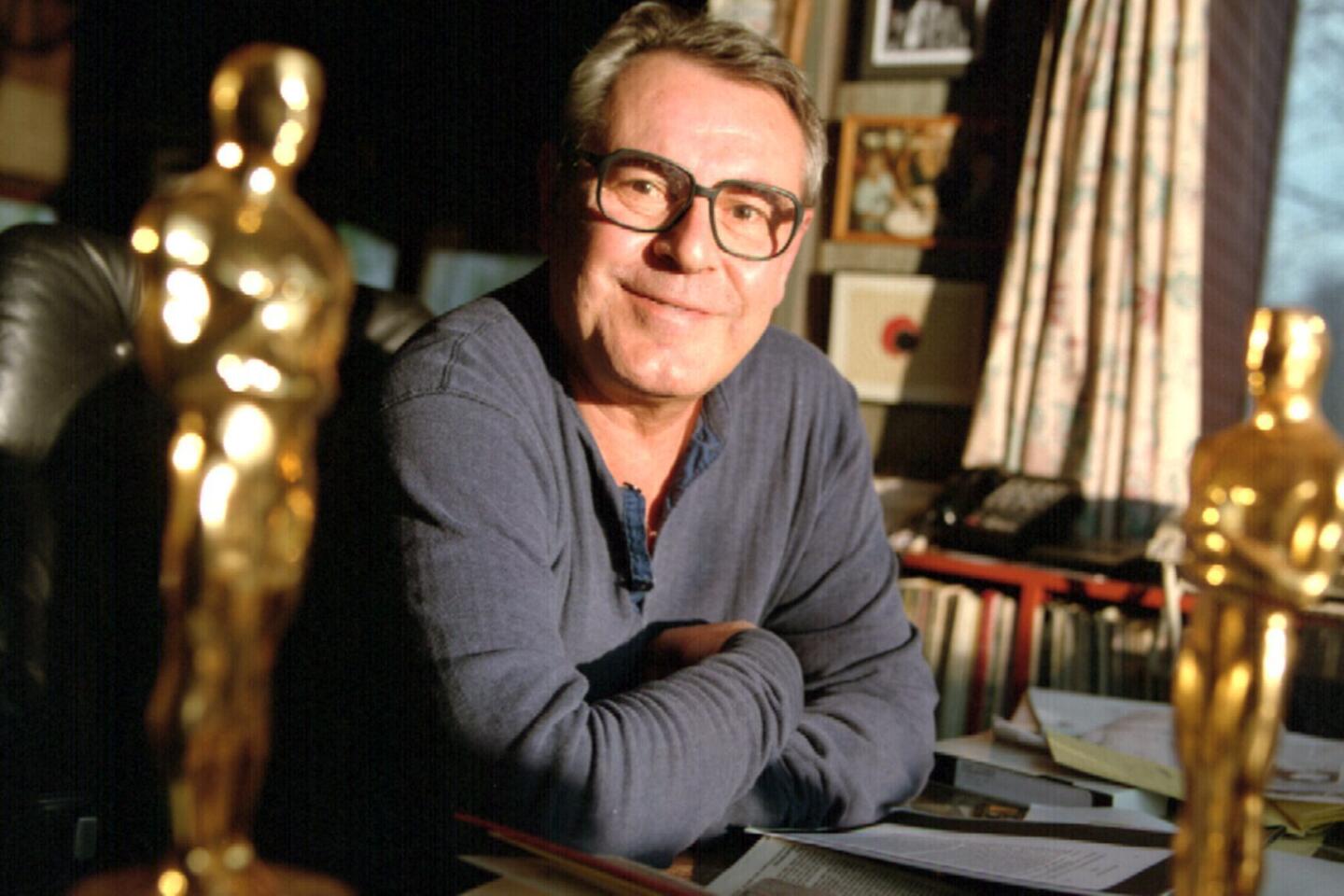

Reynolds went on to receive a Golden Globe Award and a supporting actor Oscar nomination for his performance as a porn movie director in the 1997 drama “Boogie Nights.”

In the ensuing years, he appeared in more than 50 more films and TV series, including the 2005 remake of “The Longest Yard.”

“His is a really interesting career because he went from not being taken seriously to being taken seriously back to not being taken seriously,” film historian Jeannine Basinger told The Times in 2010. “It’s kind of an interesting progression because he was a person of intelligence who understood how to manipulate his own image, and he did that very, very effectively.”

But “at a time when he came into his maturity and really did some great acting” in smaller parts in serious movies such as “Boogie Nights,” Basinger said, “it just didn’t go anywhere for him like it should have, and he didn’t get that sort of golden years of role maturity that his talent entitled him to.”

However, Reynolds kept working up until his death. He played a Reynolds-esque, aging actor in March’s “The Last Movie Star” and lined up a few other projects after that.

“Word gets out — they know before you do — that you’re hot again,” he told The Times earlier this year.

He was also set to appear in Quentin Tarantino’s star-studded Manson-murder tale, “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” but had not yet shot his scenes, The Times confirmed.

“So many people have already contacted me, to tell me how they benefited professionally and personally from my uncle’s kindness,” said Hess, Reynolds’ niece. “I want to thank all of his amazing fans who have always supported and cheered him on, through all of the hills and valleys of his life and career.”

Reynolds’ 1963 first marriage to British actress Judy Carne ended in divorce in 1966. In 1988, he married Loni Anderson, with whom he adopted their son, Quinton. The marriage ended in a highly publicized divorce in 1994.

Dennis McLellan is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Nardine Saad contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

4:16 p.m.: This story was updated with Reynolds’ cause of death.

2:50 p.m.: This story was updated with Nancy Lee Hess’ statement, reactions from Dolly Parton and Sally Field and details about Reynolds’ latest projects.

This story was originally published at 12:25 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.