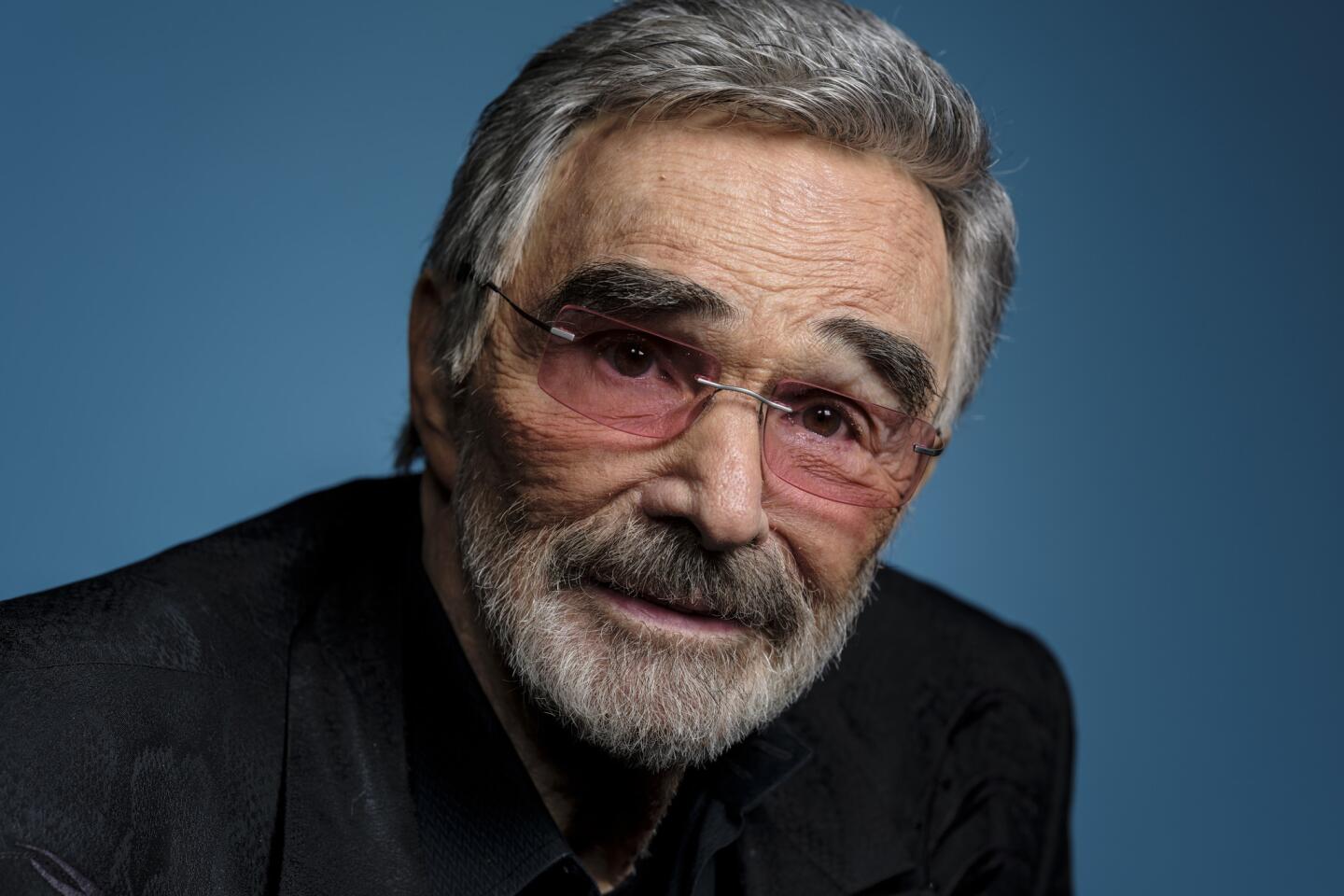

From the Archives: Burt Reynolds is the comeback kid

- Share via

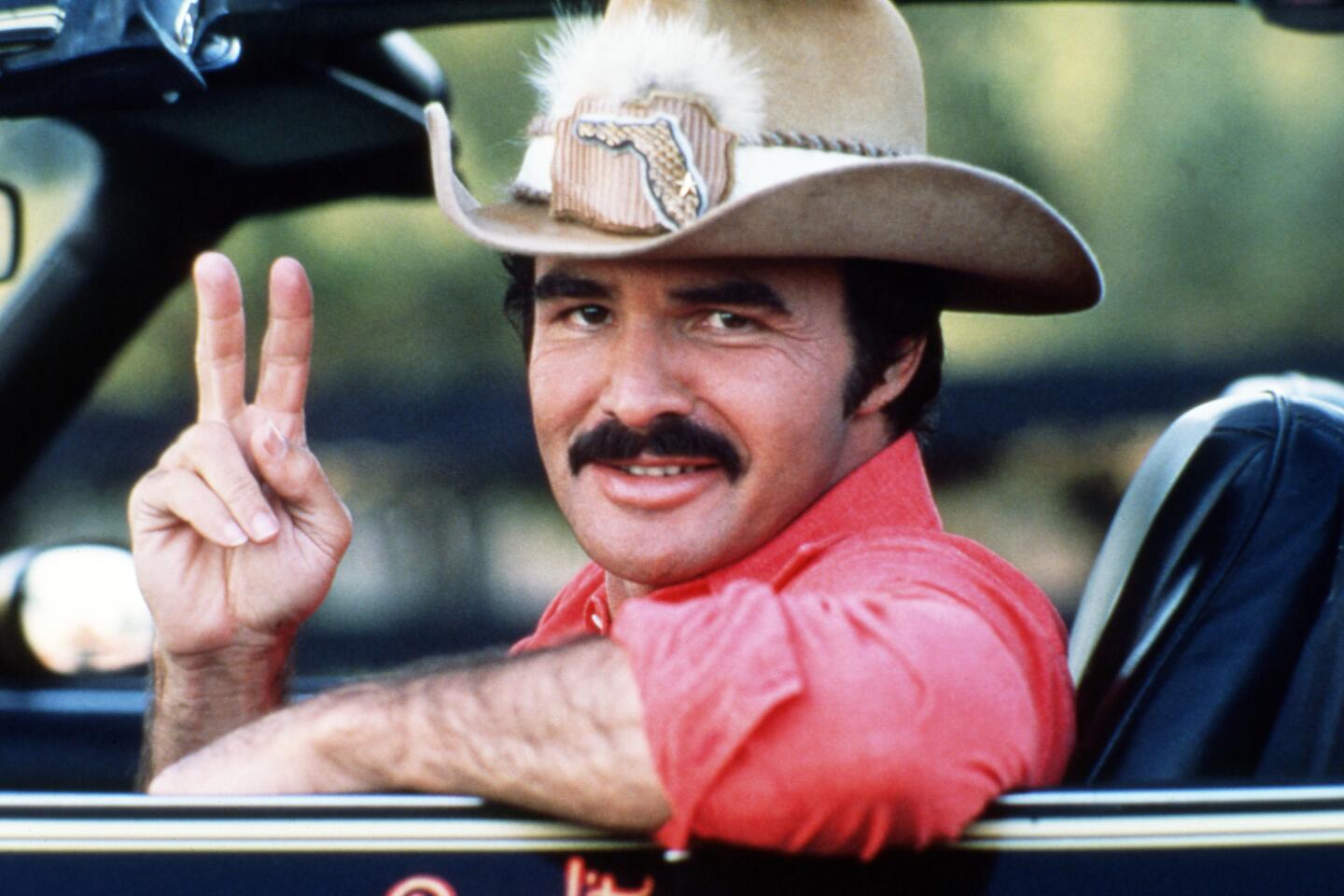

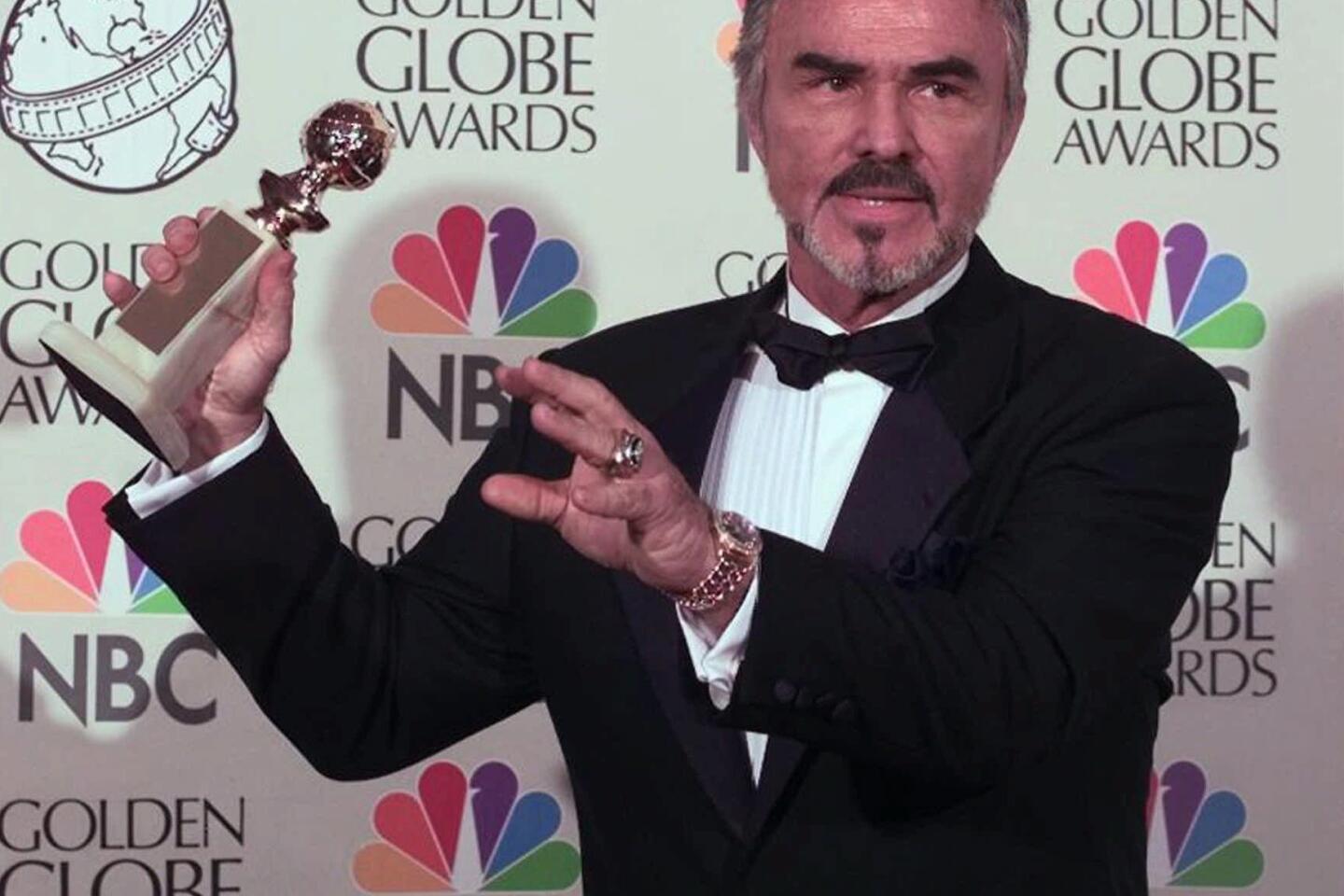

Burt Reynolds, who reigned as Hollywood’s box-office champ in the late 1970s and early ’80s in movies such as “Smokey and the Bandit” and “The Cannonball Run,” died Thursday at age 82.

Below is a Los Angeles Times story that originally published on Jan. 4, 1987, and detailed changes to the actor’s career and personal life during that decade.

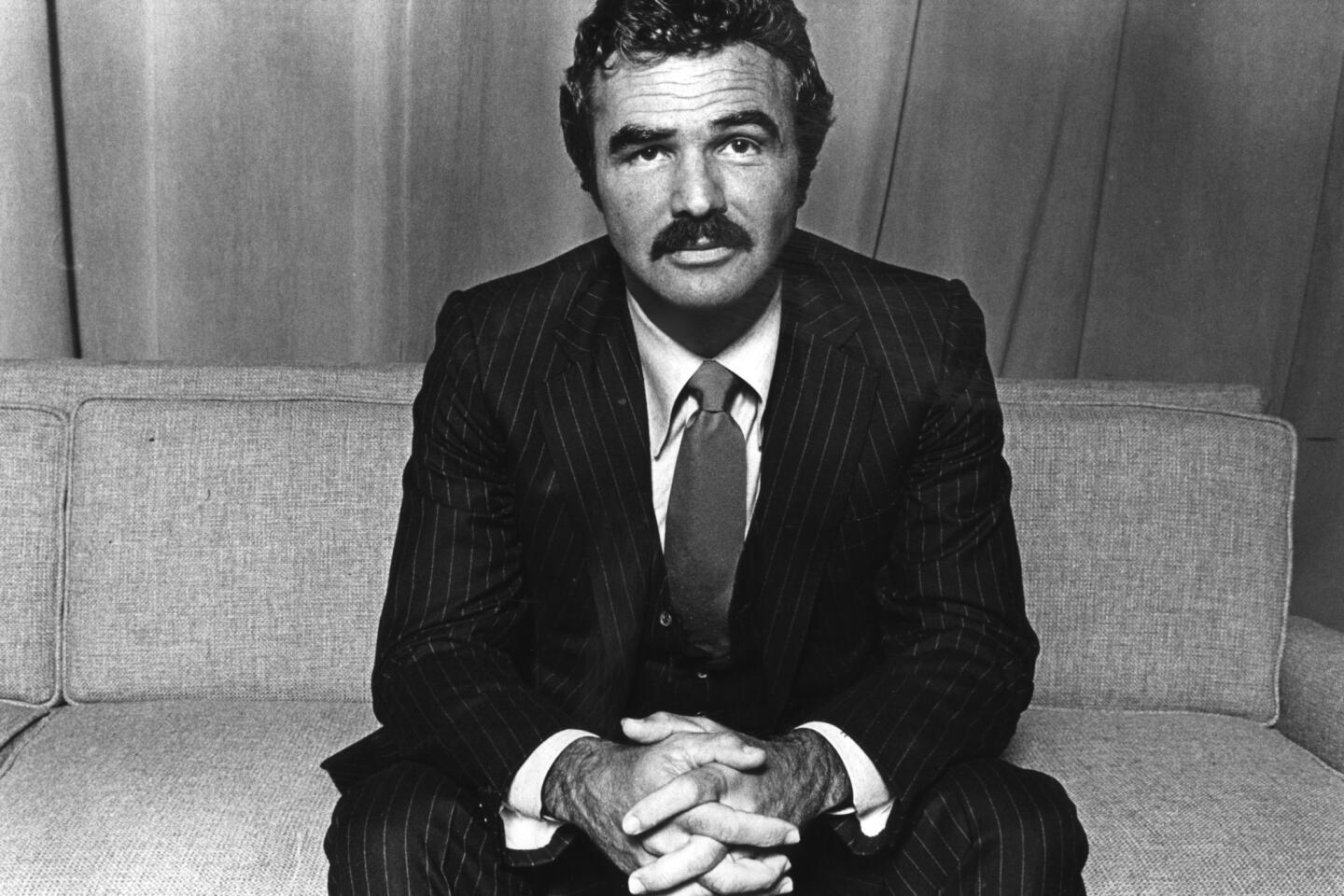

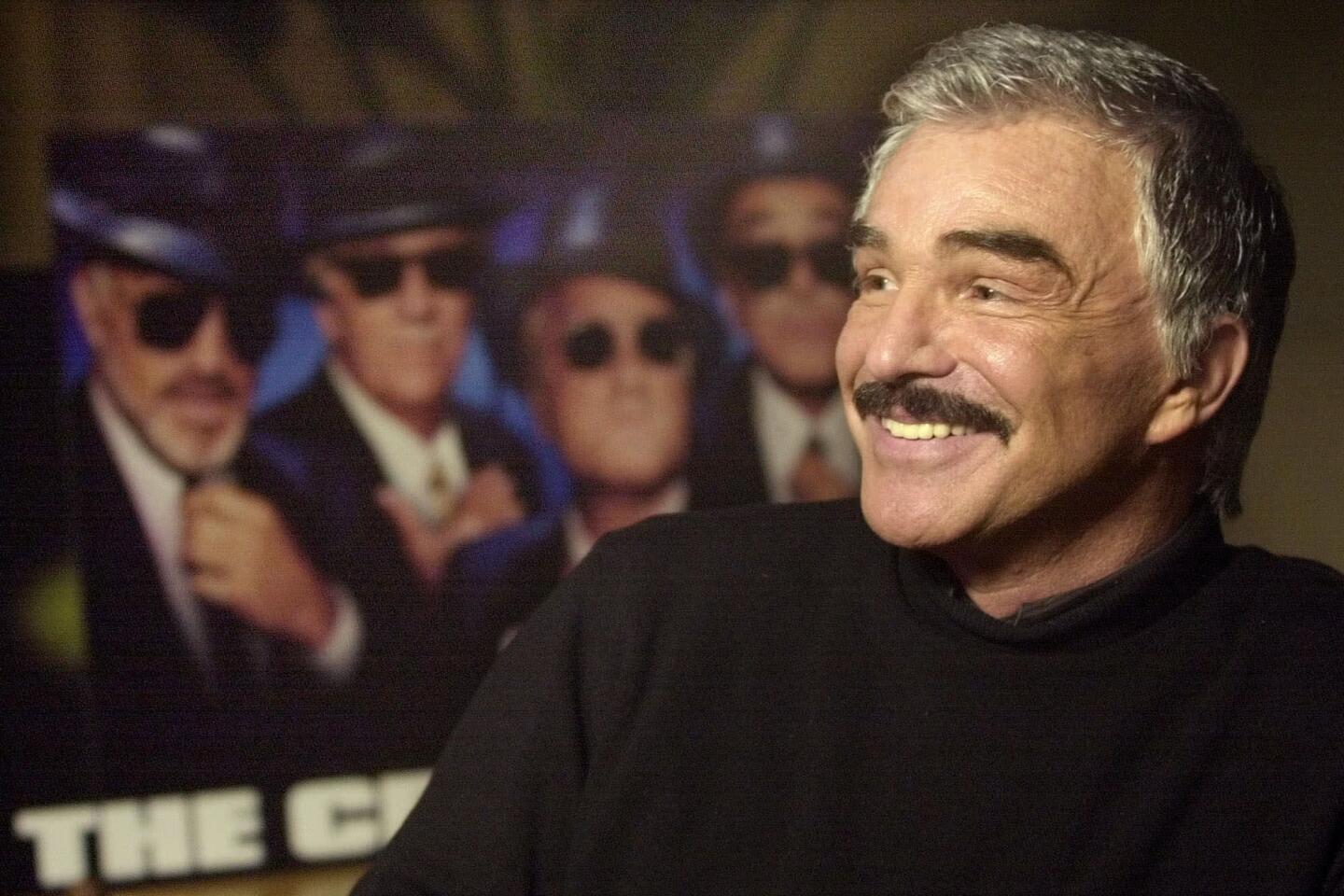

This isn’t the good ol’ Burt Reynolds that we have come to know and love. Yes, he looks like the same starkly handsome, wisecracking Reynolds — but there’s an unusual hunger about him.

He has paraded his problems, medical and otherwise, on TV talk shows with a candor that is unusual for a star of his magnitude. And his career as a movie star is in some kind of chaos.

By his own admission, he’s been his own worst enemy.

“I’m starting to lose my anger now,” he related between breaks filming “Rent-A-Cop” in Chicago. “I was real angry for a while at people that were jumping ship. The worst press I’ve ever gotten in my life has been the past two years when I wasn’t doing anything. I thought, ‘Why are they picking on me? Why aren’t they picking on Tom Cruise? I can’t get a job. I’m sick.’

“Now that I’m working again, I realize you can’t get angry at the press like they’re the enemy, which the President is doing in the Iran situation,” he went on. “I see Richard Pryor running around denying he has AIDS and I think you can’t do that. Your life goes on. ‘Just gain some weight, Richard, make some funny movies and go on with your life because there are millions of people in Middle America who don’t know the rumors.’

“And I understand the pain and anger Richard is going through now more than anybody. Nobody can get to you if you’re happy,” he added. “Once I got back into being a working actor instead of being a movie star, I realized what Clint Eastwood’s been trying to tell me for years: Life is too short for you not to do the projects you want to do with the people you like.”

The test of Reynolds’ desire to revive his career is . . . well, Cannon Films offered him a king’s ransom to do “Cannonball Run III” and he turned it down.

He related: “That would destroy everything I’m trying to do to become an actor again and not a personality or a parody. I’m not battling my way back to the top either. I had a good run at the top, which I never expected to last as long as it did. Now I feel I’ve gotten better at my craft.

“I know a lot of people in this business think I’m a has-been, but I know the public will give me another chance. I’ve got a lot to prove to a lot of people.”

What would it take to win back his fans’ respect? “I need to make some good movies,” said Reynolds with a knowing smile. “It’s as simple as that.”

After almost a three-year absence from the big silver screen, due in part to a severe inner-ear infection, Reynolds looks mighty like the Comeback Kid of the Year. Although the themes all sound awfully familiar, he’s riding high hopes for his three films coming out this year:

“Heat,” in which he plays a Las Vegas hit man, opens in this country in March. (It’s opened in Paris, where Reynolds has received rave reviews. Said Tele magazine: “Besides the fact ‘Heat’ is a great suspense (film), Burt Reynolds gives a rare intensity and surprising melancholy to a thundering character.”)

“Malone,” just shot in Vancouver for summer release, casts him as an avenging angel for a scared family threatened by a right-wing military group.

“Rent-A-Cop,” which finished filming in Chicago and now has moved to Rome for more scenes, is a possible Christmas release. It finds ex-cop Reynolds on the mean streets of Chicago trying to uncover police corruption involving a drug scandal.

Over a salad in his hotel restaurant in Vancouver, Reynolds is handed a list of his 42 films over which to reflect on his career. He looks them over--and points a finger at “Stroker Ace,” 1983.

“That’s where I lost them,” he says of his fans with a hint of sadness.

Then along came “Cannonball Run II,” “The Man Who Loved Women,” “City Heat” and “Stick.” Gone was his muscle at the box office. Gone was the respect and power that he once commanded in the industry.

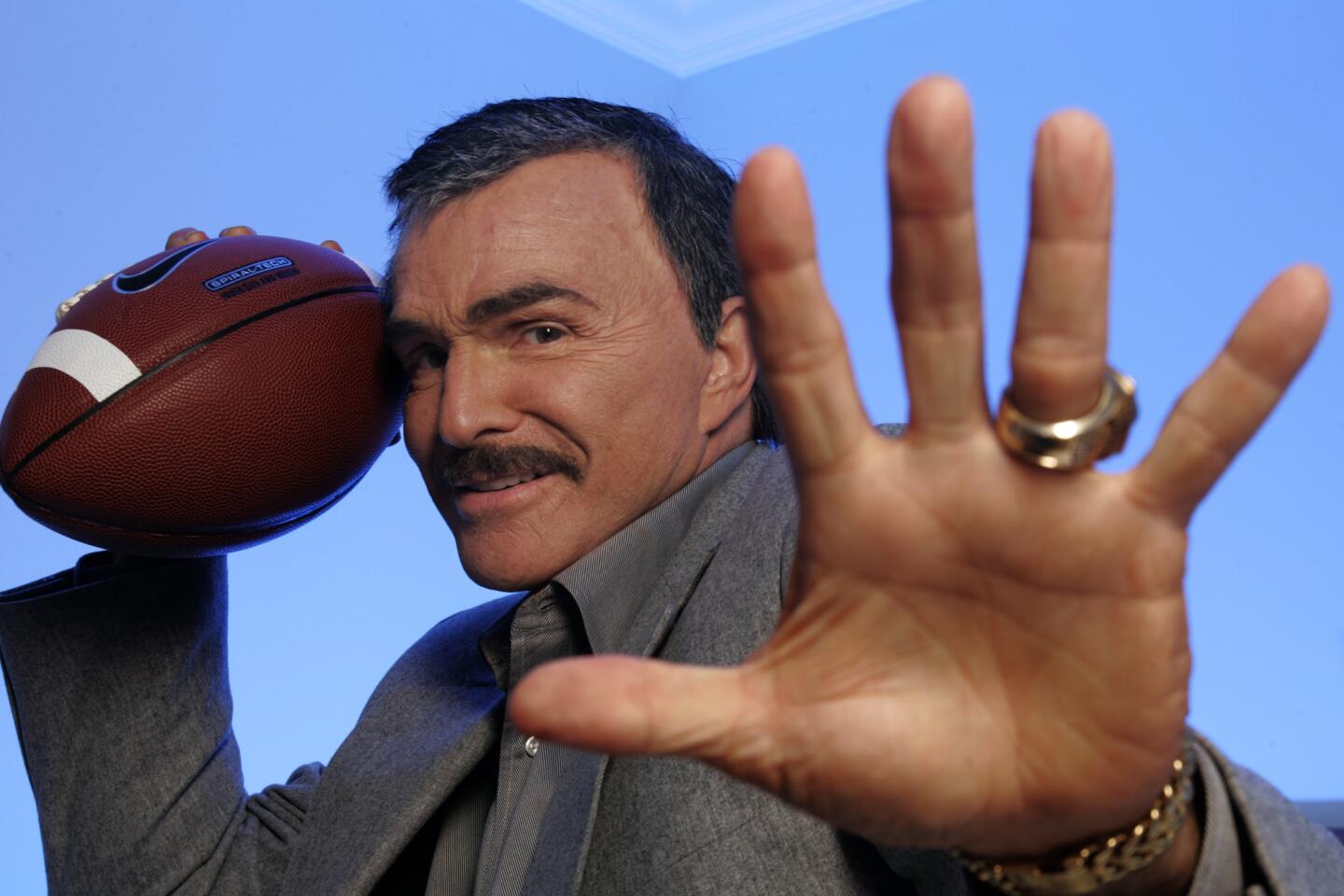

Reynolds tries to explain how “Stroker Ace” happened. He wanted to fulfill a commitment to his longtime friend, director Hal Needham (“Smokey and the Bandit”)--so he turned down the role in “Terms of Endearment” that eventually won Jack Nicholson the best supporting actor Oscar.

Screenwriter James L. Brooks told Reynolds during the filming of “Starting Over” that he was writing a role for him in his next picture, “Terms of Endearment,” which Brooks would also direct. “When it came time to choose between ‘Terms’ and ‘Stroker,’ I chose the latter because I felt I owed Hal more than I did Jim. Nobody told me I could have probably done ‘Terms’ and Universal would have waited until I was finished before making ‘Stroker.’

“I can’t believe I did all those bad films in a row until I looked at the list,” he says. “I made some movies there where I went to the well one too many times.”

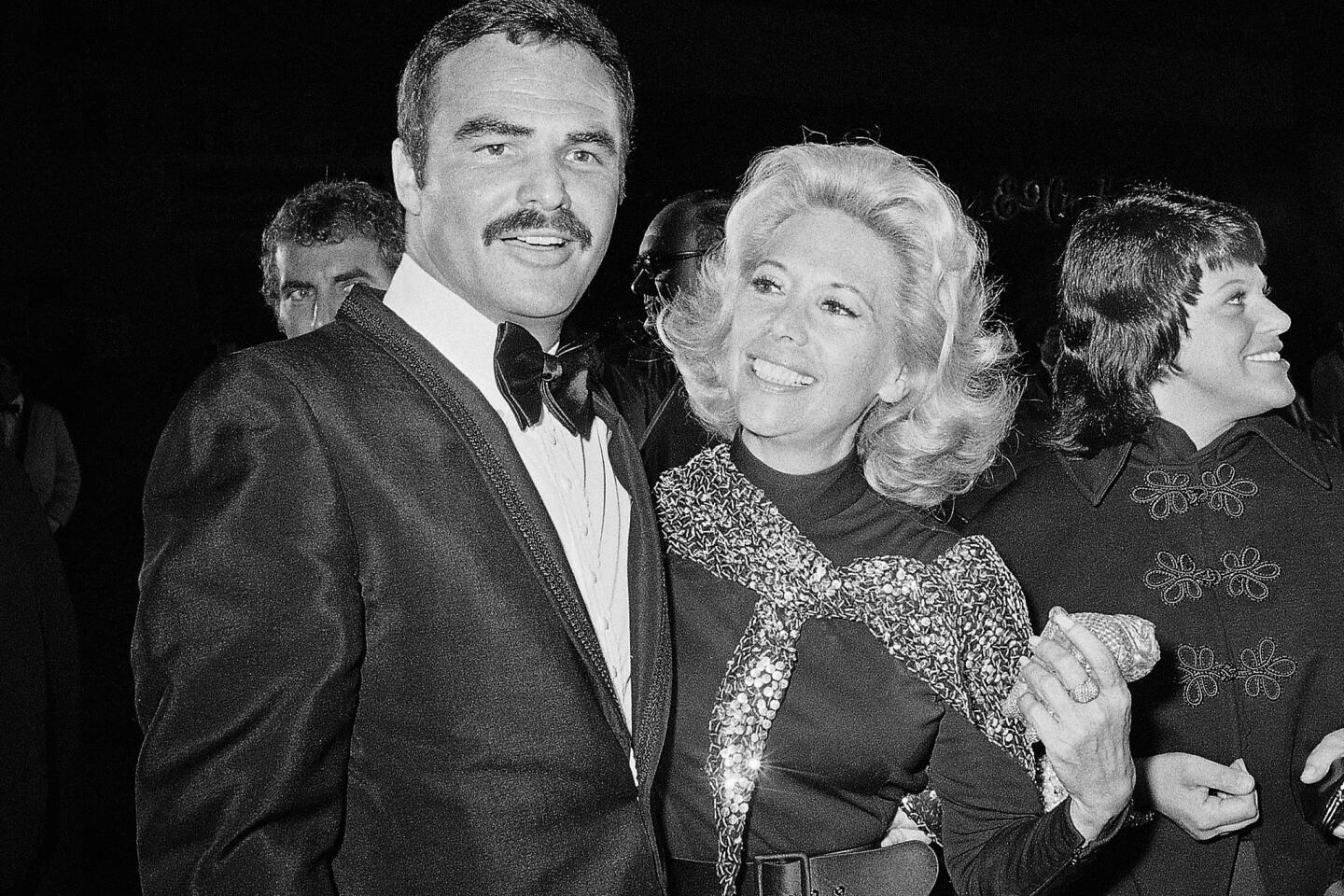

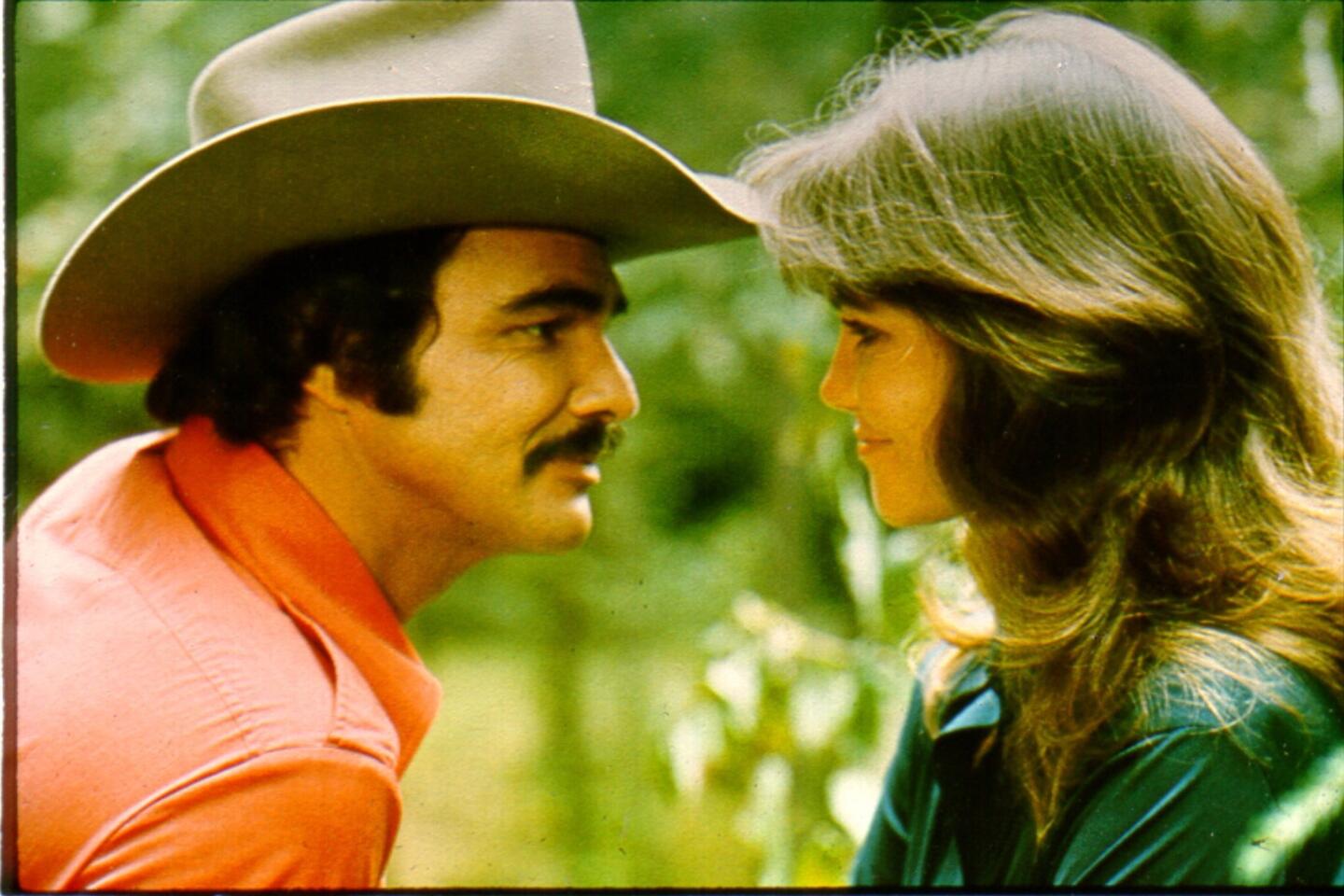

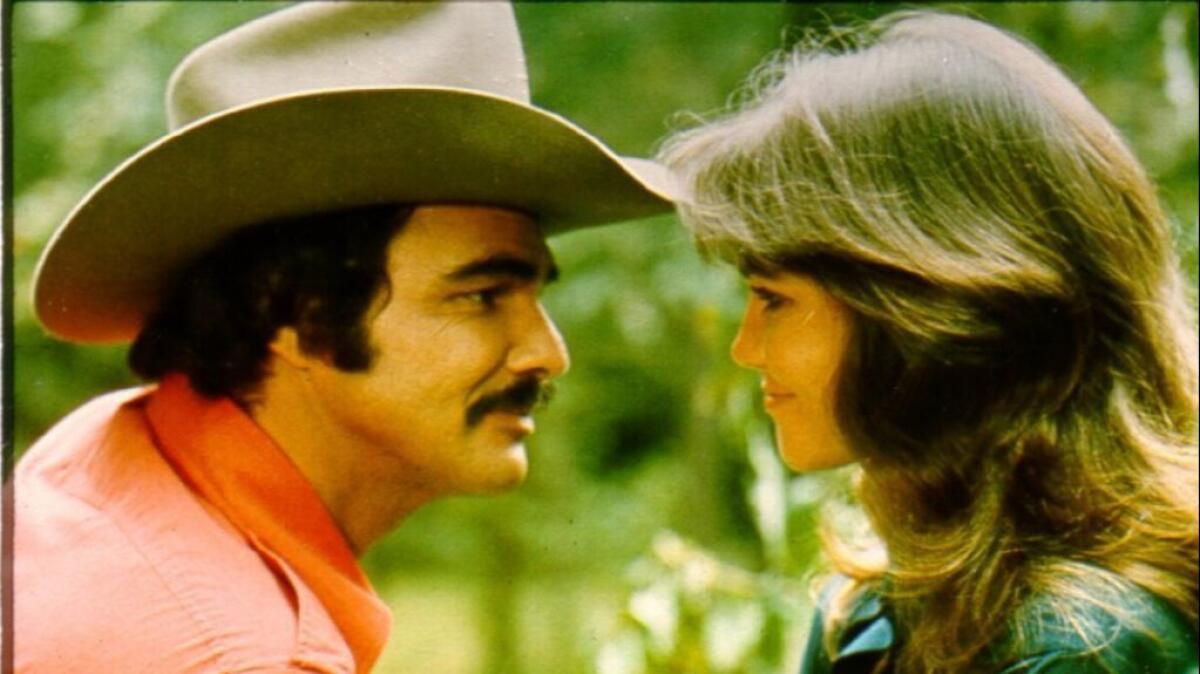

The long fall from grace is remarkable because of the tall pedestal on which the public placed him. His charm once made Reynolds the darling of the TV talk-show circuit. His romances with Dinah Shore, Sally Field and now Loni Anderson countered his image as a carefree sex symbol, an image that Reynolds successfully parodied in “Cannonball Run” and “Smokey and the Bandit,” called by Playboy as “the ‘Gone With the Wind’ of good-ol’-boy movies.”

From 1977 to 1981, Reynolds topped the Quigley Publications poll of movie exhibitors, who voted him the top box-office attraction in the country. Only Bing Crosby won the poll more consecutive years.

You understand, of course, that there’s no need to conduct any benefit concerts for the Burt Reynolds Lunch Fund. He acknowledges getting $2 million for “Heat” and $3 million each for “Malone” and “Rent-A-Cop.”

I know a lot of people in this business think I’m a has-been, but I know the public will give me another chance. I’ve got a lot to prove to a lot of people.

— Burt Reynolds

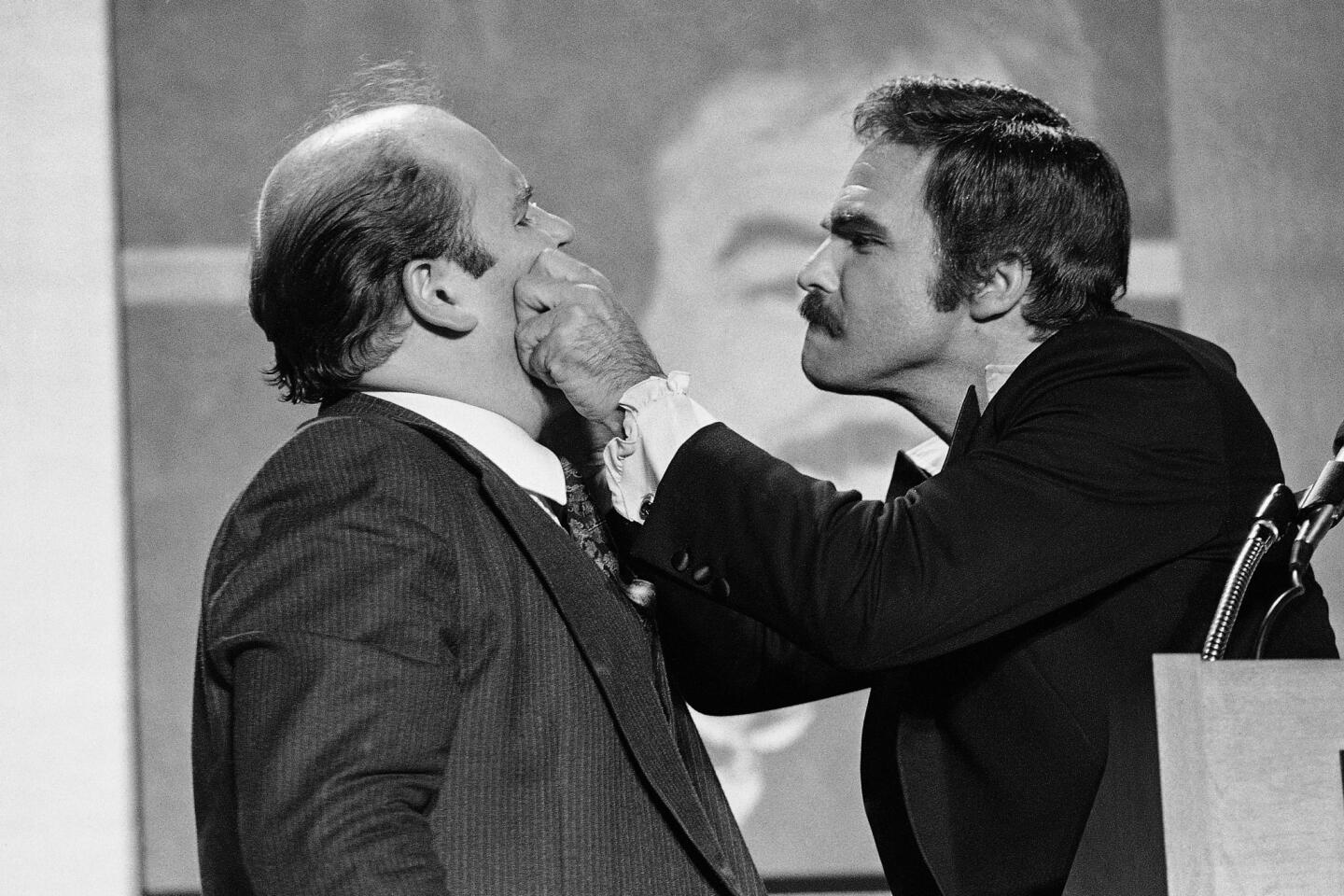

But his life is being complicated on several sides: He’s being sued by director Dick Richards for $25 million for allegedly knocking him unconscious on the Las Vegas set of “Heat”; Sally Field took some shots at her ex-lover in Playboy; the public seems more interested in whether he has AIDS (he denies it repeatedly) than in his efforts to revitalize his career; Hollywood wisdom, which sees the box office as the bottom line on any actor, places his future in serious jeopardy if he doesn’t get back in a car and crash it into something.

Reynolds appears healthy and fit. For a person whose life has been the definition of supermarket celebrity journalism the past decade, he maintains a benign mistrust of the press, yet projects a warmth and candor that is invariably endearing.

“I don’t think ‘Heat’ and ‘Malone’ are the movies that are going to change my career,” he says. “At least they are serious films, which people have told me I should have been doing for years. I don’t know how good they are, but at least I’m taking the advice now of close friends and doing films that take me out of a car.”

In his small two-room hotel suite in Vancouver, the only concession to star status is a tanning bed occupying most of the cramped living room. Reynolds’ mind often seems elsewhere while discussing “Malone.” It’s easy to understand why, even though he is polite and professional and determined not to dwell on his problems.

The major problem this day is how fast he’ll get the rewrites of tomorrow’s scene, which happens to be the finale featuring Cliff Robertson. The pages will arrive at 10 p.m. and Reynolds and Robertson, who’d only done one previous scene together, will rehearse until midnight.

On the surface, “Malone” doesn’t seem to be the type of unique character an actor waits patiently to play. It’s an action-oriented role that has been patented by Eastwood and Charles Bronson.

“I was attracted to ‘Malone’ because I thought there was a chance the movie might be more than a guy running away from his past. Let’s be honest. The movie is ‘Shane.’

“I am an ex-CIA man whose car breaks down in a small town who then gets close to a family and attempts to battle a Lyndon LaRouche character played by Cliff. I’m not doing Clint in ‘Pale Rider.’ There’s a little bit of Stallone from ‘First Blood’ in this, but I’m not playing the damaged-goods-guy Sly became in ‘Rambo.’ Just to show you how movies change, Gerard Depardieu and Christopher Lambert at one point were going to play ‘Malone.’ I wonder how this guy got rewritten into me.”

Later, drinking a Virgin Mary in a Vancouver hotel bar, Reynolds, faced with the question of whether Hollywood maintains a mutual respect for his efforts, turned suddenly silent.

Earlier, he had related with pride the fact that director Sidney Lumet had chosen him to star in “Power.” A severe inner-ear infection forced Reynolds to yield the role to Richard Gere.

“I had to campaign like hell to get ‘Starting Over.’ I remember that I was asked if I was mad I didn’t get nominated for an Oscar with that film. Any answer I gave would have upset somebody and I came off as a sour-grapes loser. I should have just said, ‘No, I wasn’t angry because I don’t like the looks of the little guy.’

“My perception of what Hollywood thinks of me is that I am potentially”--his voice drops to a near-whisper--”a good actor if I had the right material, but ‘I’m not going to be the person who gives it to him.’ I’m not bitter at anyone, I’m not angry at anyone. What I am is perplexed why people keep talking about me.”

The source of Reynolds’ perplexity is why the AIDS rumors haven’t disappeared. The latest is a cover story in the Dec. 23 issue of the tabloid Globe: “Burt Reynolds Begs Court--Keep My Medical Records Secret.”

As a major Hollywood star who has joked his way through many of his roles and been considered a joke by some of his peers as a result, Reynolds can find no humor in the two-year-long AIDS rumor.

“After a while, I begin to wonder if someone has it in for me. I’ve done ‘The Tonight Show’ and numerous interviews where I’ve denied that. I’m making three movies back to back. In order to get insurance to make these films, I’ve had to have complete physicals. What is the source of these ugly rumors and why do they continue?”

Reynolds stared away in the distance, then sipped his drink before casting a stern glance at the reporter. His tone became softer, yet remained firm.

“I’m not going to abandon my friends because somebody thinks they’re gay. I’ve always stuck by my friends in any crisis, much to the harm of my career and image, some say. That’s why I get hurt when my friends attack me in print, especially former good close friends like Sally was.”

The anger dissolved into a sardonic expression. Reynolds had refused comment on Field’s bitter and unflattering comments in the March Playboy until now.

“I’m a romanticist. I always think that the women I fall in love with, I’m going to be with them forever. I really felt I was lucky to be with Sally. The great minds at Universal never thought she was sexy or talented enough to be in ‘Smokey and the Bandit,’ but I knew then and still feel she’s a super talent.”

Reynolds paused, shook his head like someone trying to lose a bad dream. “I’m not going to get in a urinating contest with Sally,” he said with a bemused grin, “because I’d lose.”

Field’s allegation — that the real “her” stopped existing by doing everything for Reynolds — evoked a sad smile. “I don’t remember tying her up and saying, ‘If you don’t do ‘Hooper’ or ‘The End,’ I’m going to set your hair on fire.’ I read the headline in the article that said I begged her to marry me.

“Well, I’m good at some things, but begging ain’t one of them. There was a time when I thought we were going to get married, but for some reason we didn’t.

“If anybody asks me about that period in my life, it was a wonderful time and I really admire Sally’s work and I thought she liked me.

“A guy on the street never has a stranger come up to him and say he read in Playboy nasty things his ex-lover had said about him. They should, so they can understand it. I was surprised, shocked and upset by Sally’s comments. She sent me a note saying she was flippant in the interview. I don’t know how many readers Playboy has, but I’m the only one who read the note, so I didn’t think it balanced out.”

Having “been married for an hour and a half” to actress Judy Carne, Reynolds was reluctant to tie the knot with Field: “At times, I think it’s unnatural for an actor to marry an actress. I recently sent Loni to a desert island to do a movie with a good-looking guy (Perry King). That’s not something a normal person would do.

“With Sally, our relationship just ended and I don’t remember why. Sally and I never really lived together. She was always with her kids at her house, which I admired her for. I’m living with Loni now, and she’s been very supportive during these tough times and that gives me more security.”

Even now, Reynolds remains bewildered by Field’s refusal to deny he has AIDS when asked by the magazine. “That really hurt. If you’d asked Dinah, she’d be outraged. Sally’s answer was, ‘I don’t know.’ That was unbelievable.

“I was also shocked when she said in that same answer that ‘there’s always been something going on around him.’ A lot of people have told me they interpreted that remark to mean there was a lot of homosexual activity going on around me.”

Reynolds later wrote Field a note, asking if her comments were meant to imply his Southern background indicated he was prejudiced against gays. The Florida-born actor doesn’t understand what she was commenting on or what possessed her to make her remarks.

“I’m a lot of things, but I’m not prejudiced against anyone. I’m not Rock Hudson. I’m not trying to hide anything. In fact, I’ve been too much of an open jerk on these talk shows. “Sally knew I was having trouble eating and losing weight because of the problems I had with my jaw (which he hurt filming “City Heat”). I just couldn’t eat. Sally knew that. For her to say what she did hurt me in so many ways that are hard to articulate.”

During his self-imposed absence from the screen, Reynolds discovered his low profile reflected the industry’s interest in him.

“There were a few studios that didn’t call which I naively thought I had a relationship with. I thought they were my friends, and not because I had made them a couple hundred million dollars.”

Disney President Michael Eisner “didn’t stop calling. We’re still close friends, I think,” Reynolds remarked tentatively. “I know (Orion President) Mike Medavoy still cares about me and wanted me to do ‘Malone’ for his company. He also must think my name or presence means something in a picture because I’m getting $3 million for ‘Malone.’

“It’s funny, but I’ve never found any civilians in the past two years who made me feel alienated from them. The only alienation I’ve felt has been through the industry.”

Once again, Reynolds’ most trusted weapon to battle adversity became his humor. “My problem when I was down and thinking nobody liked me was that I was looking in all the wrong places . . . like newspapers and television,” he quipped. “The public always liked me. Every day I went out to my mailbox, there would be a bus from the Hollywood tour of the stars. The people would ask me to sign their maps and get disappointed when I joked that I had retired. Across town in a certain black tower they were trying to make me retire.”

It’s no secret that Universal (where the so-called “Black Tower” houses its executives) was reluctant to release “Stick,” the last film he starred in. Based on a popular Elmore Leonard novel, “Stick” had a gritty street mentality that contrasted the glossy criminal mentality of its affluent villains. This was territory that Reynolds, who also directed, had done an excellent job presenting in the same dual capacity on “Sharkey’s Machine.”

Reynolds breathed a heavy sigh, took a long sip of his drink and tilted his head downward before replying. “I wanted to make that movie as soon as I read the book. I respected Leonard’s work. I felt I knew that Florida way of life, having been raised in the state. And I was that guy!”

What went wrong? “I turned in my cut of the picture and truly thought I had made a good film. Word got back to me quickly that the people in the Black Tower wanted a few changes,” Reynolds said.

The studio pulled the movie from its release schedule and asked Reynolds to reshoot the second half of the film. A new writer was brought in along with a tired (for Reynolds) subplot involving his character reuniting with his daughter post-prison. The first half of the movie captured the authenticity of Leonard’s prose and the action style of a good “Miami Vice” episode. The second half was clearly another picture and one far inferior to its source material.

“I gave up on the film. I didn’t fight them. I let them get the best of me,” said Reynolds recalling that his agent at the time told him that it would help his career if he went along with the suggestions of the Universal executives.

“Leonard saw the film the day he was interviewed for a Newsweek cover and told them he hated it. After his comment, every critic attacked the film and he wouldn’t talk to me. When I reshot the film, I was just going through the motions. I’m not proud of what I did, but I take responsibility for my actions. All I can say--and this is not in way of a defense--is if you liked the first part of ‘Stick,’ that’s what I was trying to achieve throughout.”

Prior to “Stick,” Reynolds was riding a four-film losing streak, critically speaking. He had followed “Stroker Ace” with director Blake Edwards’ remake of “The Man Who Loved Women”; a money-making sequel, “Cannonball Run II,” and his highly anticipated pairing with longtime friend Clint Eastwood in “City Heat.”

What started out as a dream team quickly became a nightmare for Reynolds. “If you could just release the announcement for ‘City Heat’ and not have to look at the film, it’d be the most successful picture I’d ever been in,” Reynolds joked.

Edwards was scheduled to direct his original script entitled “Kansas City Jazz” (later retitled “City Heat”), a Prohibition comedy with Reynolds as a lighthearted detective and Eastwood as a sheriff determined to put him in his place.

While discussing it, Reynolds appears to be balancing friendships with Eastwood and Edwards that he obviously treasures.

They all met and “Blake laid out his way for Clint to play his part. To me, it was clearly apparent that Blake’s way was in no way how Clint saw the part. Clint didn’t say anything except his Gary Cooper comments like ‘Yup’ and ‘Nope.’ Clint and I went home in his truck and he still didn’t say anything until we were halfway there.

“Finally he said, ‘I guess this won’t be the film we do together.’ I said, ‘I didn’t think so.’ Warner Bros. really wanted to make the film. I think they thought like I did that it would be one of those pictures which would look great in the catalogue.”

Eastwood approved of Richard Benjamin to replace Edwards. “Clint likes a director he gets along with, which makes a lot of sense to me--especially now,” recalled Reynolds, his remark referring to his recent tiffing with director Dick Richards. “Blake’s dismissal hurt him badly. I don’t think he’s ever gotten over it.”

The picture still faced many problems. French actress Clio Goldsmith was soon replaced by Madeline Kahn. Then Reynolds hurt his jaw doing a fight in the first scene. The injury would cause him to spend much of the next two years seeking dental assistance and, due to his difficulty in eating, would fuel the AIDS rumor regarding his extreme loss of weight.

The damage “City Heat” did to Reynolds’ career had an equally demoralizing effect:

“Ten days after shooting began, I knew I was going to take the fall. Clint was playing formula Clint that always worked for Clint. I was playing Jack Lemmon in this strange film where people were getting blown away. I never read a review of the film, because I knew I was going to get killed by the critics,” Reynolds claimed with an absence of malice.

“The public wanted ‘Boom Town’ or to see us in a contemporary film. They didn’t want ‘Dirty Harry vs. the Wimp.’ It’s regrettable the material wasn’t there, because Hollywood or maybe just Warner Bros. will never let Clint and I act together again.”

The “City Heat” fallout, Reynolds fears, may mean two major stars of equal stature won’t make films together in the near future. “It’s always difficult when you get two leading men on the screen. If I could get Robert Towne excited about writing for two guys, maybe I could get a project done,” Reynolds remarks, adding with a shrug, “If they write for two guys today, it’s Rob Lowe and Emilio Estevez.”

Reynolds has been reconsidering the type of roles he’s best suited for in the future. In “Heat,” “Malone” and “Rent-A-Cop,” Reynolds portrays men of action and violence with their own honor code. The roles are strong and feature many physical scenes that should silence critics about his alleged failing health;indeed, the performance that Reynolds gives as a Las Vegas loner on the cutting edge of self-destruction in “Heat” may well be his best since the underrated “Sharkey’s Machine.”

“They don’t write aggressive characters for my age anymore. I’m not the swinging bachelor who stepped out of a Cosmopolitan layout and into your bedroom now, either. In the past, I didn’t allow myself to be open to new writers or risky roles. I wanted to do them, but I may have isolated myself too much when I was on top.”

Look over a list of Reynolds’ 42 films and you notice an absence of top directors. Could he call a director, like Paul Newman did with Martin Scorsese on “The Color of Money,” and suggest they discuss working together?

“Paul had the great idea of playing ‘The Hustler’ 25 years later. Can you imagine me phoning a major director and asking if they wanted to direct me as ‘The Bandit’ 25 years later?

“I don’t have the cachet Paul has. He could just play characters he did in the past that started with the letter H. I thought of calling (“Deliverance” director) John Boorman again and asking him if he wanted to send Ned (Beatty) and Jon (Voight) and I up the river again.”

The public always liked me. Every day I went out to my mailbox, there would be a bus from the Hollywood tour of the stars.

— Burt Reynolds

Reynolds admitted that many of the A-list directors don’t call him. Only Norman Jewison, who directed “Best Friends,” and Sidney Lumet have expressed interested in working with the affable actor. Reynolds would have loved to have done either Nick Nolte or Richard Dreyfuss’ role for Paul Mazursky in “Down and Out in Beverly Hills.”

“I’m not saying I could have done them better than Nick or Richard, but the last three years I’ve felt like I was down and out in Beverly Hills,” Reynolds joked.

He added, respectfully:”I used to admire how Sally would call a director and ask him to work with her. I should be able to do that, but I can’t. I would have loved to have worked for Peter Weir in ‘Witness.’ I thought it was a weak script, but he and Harrison (Ford)made it into an almost perfect movie.”

In 1977, Francis Coppola courted Reynolds, then the nation’s top box-office star, to star in a movie entitled “Tucker” based on the man who invented the Model T. At Coppola’s request, Reynolds went to San Francisco, ate a wonderful dinner with the director’s family and spent the night.

Ten years later, the memory still pains Reynolds.

“The next day, Francis showed me seven different endings of ‘Apocalypse Now’ and asked me which one I liked. Then we watched home movies of Tucker, who looked exactly like my dad. By the time I left, there was no doubt he wanted nobody but me.”

Four days later, Reynolds received a call from a Paramount executive telling him they wanted to make “Tucker,” but not Coppola’s six other projects.

“Francis had tied all six projects, which were mostly films he intended just to produce, to me just because I was the flavor of the month. I was really hurt by it. I called Francis and said, ‘Don’t you want me without using me to push through your other six projects?’ ” Reynolds’ bitterness still is apparent. “His answer lies in the fact that the movie didn’t get made. The ‘Tucker’ incident was very sad.”

Still, Reynolds cast his pride aside after reading the book “Gardens of Stone” last year. The actor asked to meet with Coppola, offered to take a screen test, and felt hurt when the director cast James Caan in the lead instead.

Reynolds called “Heat” writer William Goldman to express interest in making a movie of his novel but, though tempted, has never phoned an actress for a possible pairing. “The time to call someone is when you’re on top of your game. Now, quite honestly, I don’t want a top actress to think they’re giving me a break and helping me. I’d like them to call me because they think I’m the best guy for a part.”

When “Malone” shifted location to a secluded horse farm an hour’s drive from downtown Vancouver, Reynolds’ ability and patience was put to a test. Despite an early morning call, Reynolds had only been asked to do two close-up shots. Cliff Robertson was inside a small section of a horse barn that had been converted into a computer center for the climactic scene. Tension was high because Robertson needed to complete his work this day and couldn’t adjust his schedule for any added shooting.

Director Harley Cokliss, whose previous film was the ill-received “Black Moon Rising,” seemed more concerned with Robertson remaining within camera range in the narrow room rather than with the lengthy dialogue he had to deliver.

Reynolds, who has directed four films, sensed Robertson’s anxiety and offered his assistance. Reynolds sat off-camera in a cramped corner and made sure nobody got within Robertson’s sight lines while feeding him his cues. A director himself (“J.W. Coop”), Robertson appreciated Reynolds’ help, especially when a muffed line was turned into a tension-cracking ad-lib by Reynolds.

During an endless series of retakes, the usually affable Robertson was visibly frustrated. Reynolds took him aside and softly gave him advice on how to play the scene to avoid fighting the director. Reynolds wouldn’t repeat his conversation, but Robertson later hinted at its content:”Burt knew what was happening in there could have turned ugly. He made sure I stayed focused on what my character needed to get across instead of listening to other people try to tell me I was moving out of focus. What Burt did was a very nice and needed gesture that helped me do the scene right.”

When asked why he agreed to the director, Reynolds replied: “Steven Spielberg and George Lucas told me he was good.” Reynolds hadn’t seen “Black Moon Rising” — which would seem like a major oversight.

“Listen, I have to start doing my homework. I have to start writing names down of writers and actors and directors of movies I like,” Reynolds admitted, fully aware of the position of his star and the power he has at present.

“I’m hungry again. A lot of people think I’ve topped out in terms of commercial success, and they may be right. The blue-collar actor in me wants to keep working.”

He’s writing his autobiography, developing a game show for Disney called “Win, Lose or Draw,” doing a comedy special for ABC on mid-life crisis and planning to direct a movie that he won’t star in next summer.

A marriage to his longtime girlfriend, actress Loni Anderson, may also be in the works. “She’s passed all my tests, including, ‘Would you rather be with me or have your photo on the cover of People?’”

Reynolds said that in the past two years he’s done a lot of soul-searching and discovered that he doesn’t have many close friends.

“Sure, a lot of people have a picture of me, but if you flip it over, I bet you’ll find a photo of Tom Selleck. In the past, I was naive to think that because (former Universal Pictures President) Frank Price asked me for a photo, that we were suddenly good friends. Now I won’t go to private parties where there’s over 10 people. I used to go to parties and see tons of people before I realized it was just an opening or something to get on ‘Entertainment Tonight.’

“When you go through what I have recently, you learn to go for the laughs in your life, because that’s the only thing they can’t take away from you--but they’ll still try.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.