The long, tortured journey to bring rail back to Los Angeles

- Share via

Los Angeles voters will decide next week whether to make another major expansion in the region’s rail network.

Measure M would raise an estimated $120 billion over four decades to fund transit operations. They money would be used to add a dozen rail lines and extensions, including a rail tunnel through the Sepulveda Pass and connections to Pacoima, Norwalk, Claremont and Torrance.

Over the last three decades, L.A. County has built a new rail network largely from scratch.

But it took decades to get there. After World War II, the region’s once-mighty streetcar services began to fade and building freeways became the top transportation priority. By the 1960s, planners began proposing new rail routes. But these plans faced numerous problems. Several attempts to get taxpayers to finance these rail networks failed at the ballot box.

Here’s a history of the high and lows of L.A. transportation dreaming, from the pages of The Times:

Freeway master plan

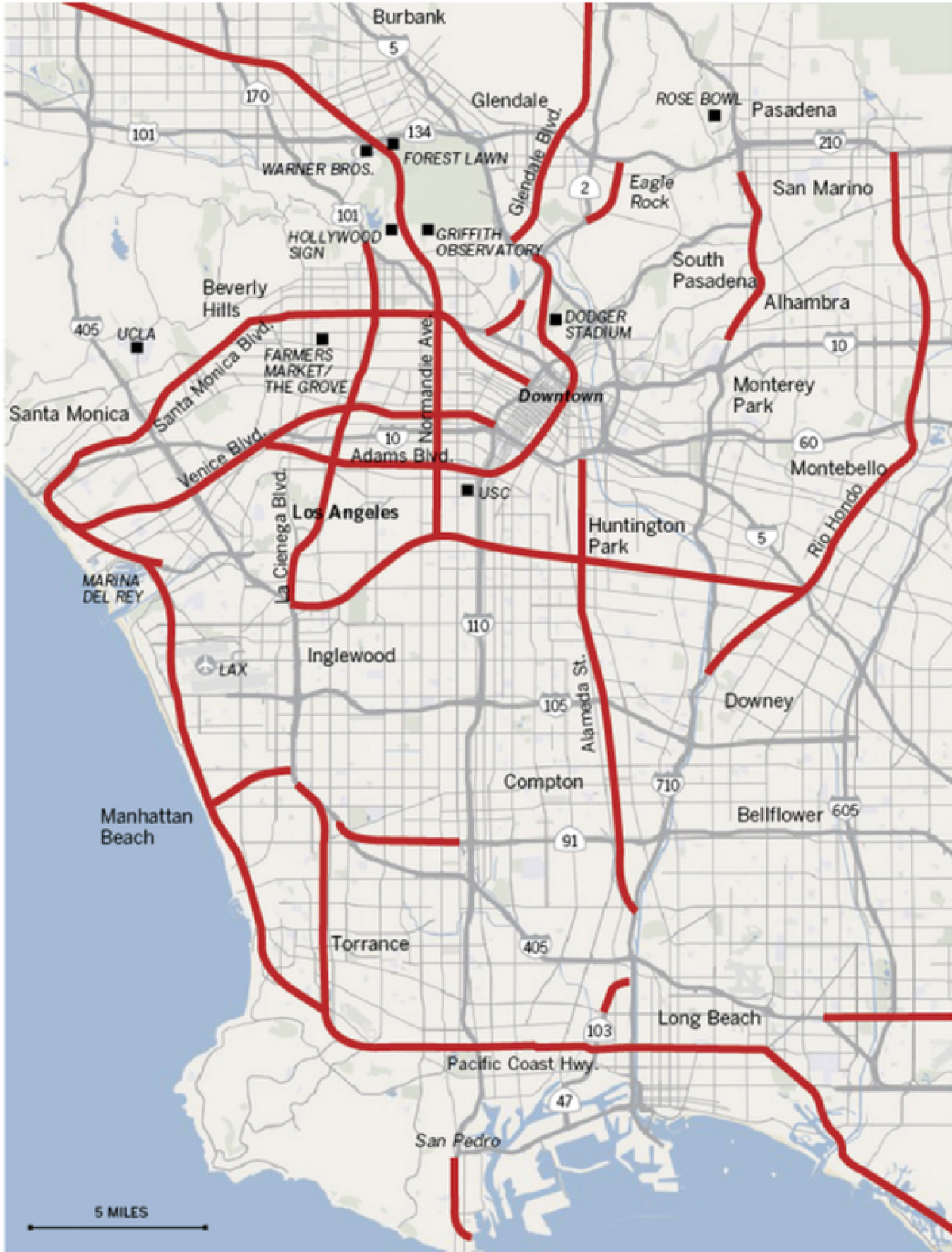

After World War II, transportation planners crisscrossed the county with freeways — the 10, 101, 4, 60, 91, the 210 and more.

But officials proposed many other freeways that never got built because of money issues, political opposition or both.

The Beverly Hills Freeway was supposed to connect the 101 and 405 freeways along Santa Monica Boulevard and Melrose Avenue. Another freeway was supposed to run alongside La Cienega Boulevard, La Brea and Highland avenues, connecting Los Angeles International Airport to the Hollywood Bowl.

Routes were also planned following Pacific Coast Highway and train tracks that would have connected Manhattan Beach to the 405.

Some of the worst traffic today exists where proposed freeways were supposed to go.

One example is Century City, L.A.’s “second downtown” that was originally conceived with close access to the Beverly Hills Freeway. Century City rose, but the freeway plan was eventually killed.

L.A. monorail

In 1960, planners unveiled an ambitious monorail proposal. The $539-million project (in 1960 dollars) would create more than 70 miles of rail, much of it elevated.

The plan brought much excitement. But opposition began to form, both over the price tag and from critics who didn’t want an elevated rail line running down Wilshire Boulevard.

For a while, officials talked about turning the Wilshire leg into a subway.

Then a scaled-back monorail plan was submitted.

It didn’t go very far, though planners continued to talk about various monorail routes well into the 1970s.

Downtown People Mover

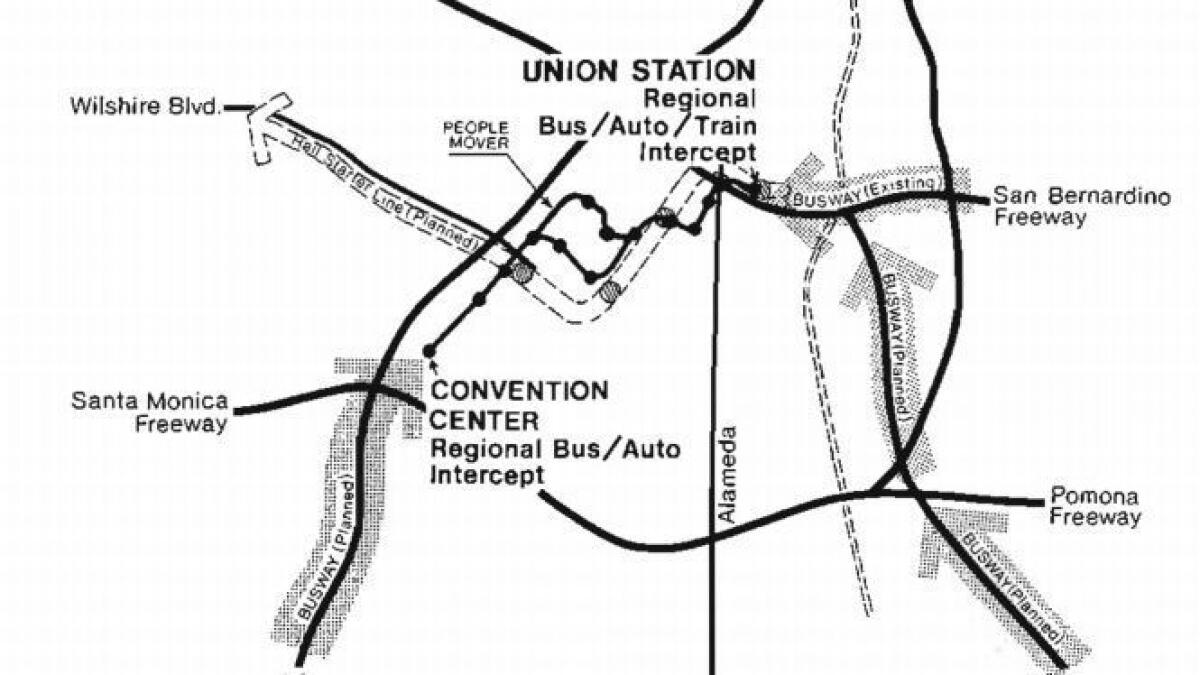

The development of skyscrapers on Bunker Hill in the 1970s prompted another mass transit concept: the People Mover.

The proposal first surfaced in 1973. The system would pass through Bunker Hill and link two huge commuter parking garages on the east and west edges of downtown. In 1976, the federal government selected Los Angeles to be one of a handful of cities where people mover projects would be built and their value demonstrated. The city began digging a tunnel under Bunker Hill that would serve as part of the route.

But in 1981, the $259-million automated shuttle system was killed by the Reagan administration.

For years later, the city debated what do with the partly completed passageway, which became known as “the Tunnel to Nowhere.”

Los Angeles River freeway

As traffic worsened in the 1980s, a new freeway idea took root: Why not turn the L.A. River, which runs through the heart of the county, into a roadway?

The freeway would consist of two segments: a stretch running from the west San Fernando Valley to downtown Los Angeles reserved for buses, vans and carpoolers, and a stretch extending south from downtown to Long Beach for trucks. The freeway would not take up the entire river, and parts still could be used for flood control.

During heavy rains, the freeway would be closed.

The idea was never taken seriously in some circles. Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley opposed it, saying he wanted the long-neglected river restored as parkland and open space, with hiking trails and bike paths.

Another fanciful plan to run hovercraft vessels on the river also went nowhere.

ALSO

Southern California's deadliest quake may have been caused by oil drilling, study says

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.