L.A.’s traffic battle plan: More rail, but also Uber, bicycles, cars and a lot more dense development

- Share via

From the beginning, reintroducing rail into a region dominated and dependent on the car has been a daunting task.

Officials have spent billions of dollars to build more than 100 miles of passenger rail to connect the far-flung edges of Los Angeles County, from Azusa to Santa Monica, and North Hollywood to Long Beach.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s newest rail line, between downtown Los Angeles and the Westside, is packed with riders. But swaying Southern California’s allegiance to the car has proved difficult. Ridership has faltered on Metro’s expansive bus system, and the vast majority of the region’s commuters continue to drive alone to work.

The long, tortured journey to bring rail back to Los Angeles »

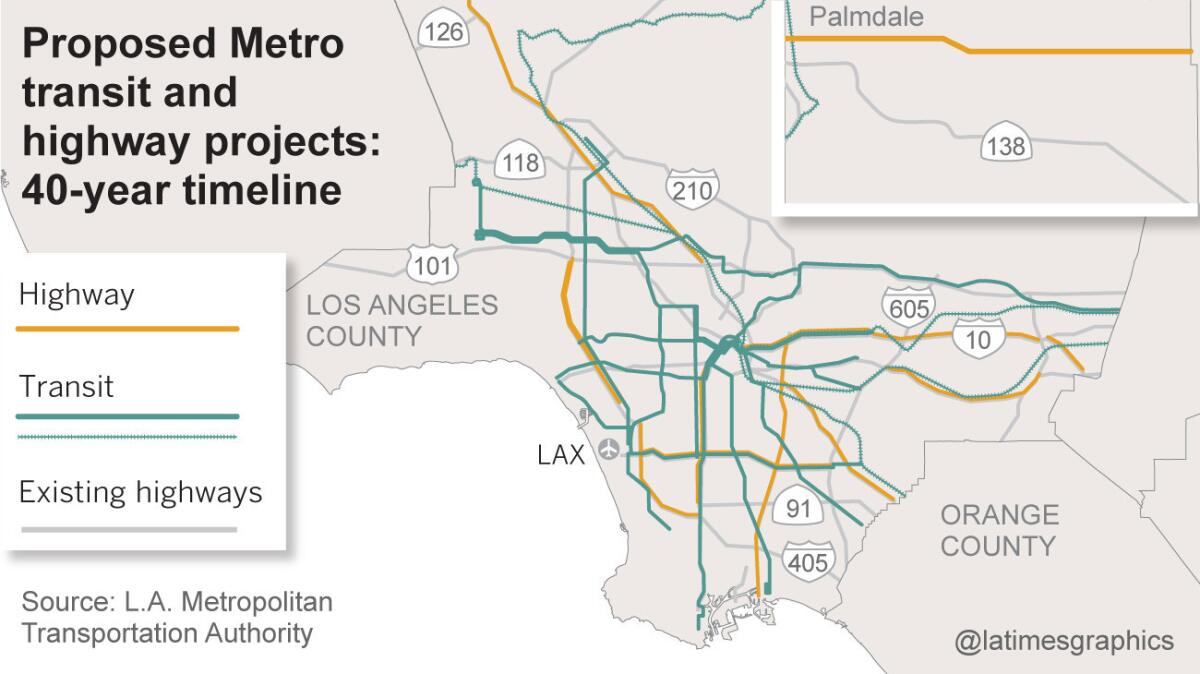

Next week, voters will decide whether to redouble the county’s transit building boom through Measure M, a half-cent sales tax increase to nearly double the length of the rail network.

Adding more rapid transit will add options for commuters, experts say, but they stress that rail alone won’t solve L.A.’s infamous congestion. Rather than a total reliance on transit, Southern California’s growth will probably follow a “hybrid approach” to mobility, incorporating rail, buses, walking and biking, shared mobility services such as Uber and Lyft — and, yes, cars.

Moreover, they say, the county’s 88 cities will have to welcome taller commercial and residential developments along major boulevards and within walking distance of transit lines to encourage drivers to get out from behind the wheel.

Metro Chief Executive Officer Phil Washington has said he hopes to convert 20% to 25% of the county’s population into regular transit riders, more than three times the current rate.

The nearly $42 billion that Measure M would set aside for new rail and bus rapid transit construction could help achieve that goal, proponents say, and will provide more options for commuters as traffic gets worse.

But to meet that ambitious shift toward transit, Southern California would have to add more apartments and offices along major arteries and near transit, making it easier for people to move through the region without driving, said Lisa Schweitzer, an associate professor of urban planning at USC.

“I don’t think that happens by just investing in transit,” she said. The lack of dense development near stations, she said, means potential ridership is “severely limited.”

To be most effective, Measure M investments should be coupled with policies that discourage driving, said Juan Matute, associate director of the UCLA Lewis Center and Institute of Transportation Studies. Those could include raising the gas tax, tolling certain routes or areas, or charging more for parking.

Without those changes, he said, Los Angeles County’s major investment in transit could resemble a headline from The Onion that’s a favorite among urban planners: “98 Percent Of US Commuters Favor Public Transportation For Others.”

For people who are looking for an easier way to get around, the Measure M system will provide it.

— Juan Matute, associate director of the UCLA Lewis Center and Institute of Transportation Studies

“You will have people who are stubborn, saying they want to drive the same amount in 2038 that they did in 2016, even if it’s more expensive or more difficult,” Matute said, adding that the region will never completely abandon the “flexible mobility” of cars. “But for people who are looking for an easier way to get around, the Measure M system will provide it.”

Measure M would raise the county’s base sales tax rate by a half-cent, to 9.5%, and would indefinitely extend an existing half-cent tax that will otherwise expire in 2039. The levy would raise an estimated $120 billion over the first four decades.

Critics of Measure M have said that the tax’s no-sunset clause makes it difficult for voters to hold Metro accountable, particularly if the projects face cost overruns or schedule delays during construction.

“When you opened your first checking account, your mom and dad told you not to ever give out a blank check,” Dan Medina, a Gardena councilman, said at a recent news conference. “If you vote for Measure M, that’s exactly what you’re doing.”

Your mom and dad told you not to ever give out a blank check. If you vote for Measure M, that’s exactly what you’re doing.

— Gardena councilman Dan Medina

But even skeptics acknowledge that there are few viable options other than adding more mass transit as L.A. tries to tame traffic and deal with population growth.

Congestion in 2057 will be 15% lower than it otherwise would be if Measure M passes, Metro researchers say.

If Measure M misses the required two-thirds majority, always a high hurdle, Metro will continue to receive more than $2.5 billion in revenue annually from three other half-cent sales taxes. Construction will continue on rail lines underway through downtown, the Miracle Mile and South Los Angeles.

But officials would not have new revenue to borrow against to build new rail lines faster, including a tunnel through the Sepulveda Pass, and extensions through the South Bay, the San Fernando Valley, the San Gabriel Valley and the southeast county.

The measure would also accelerate construction on the Purple Line subway from Century City to Westwood by more than a decade.

Some arteries, including Vermont Avenue, would see the arrival of so-called bus rapid transit, which can include platforms, bus-only lanes, fewer stops and other rail-like features.

Vermont has been a candidate for rail since officials considered building the first modern rail line in Los Angeles. Riders on buses along the congested north-south corridor make about 45,000 trips per day, more than some Metro rail lines.

The bus rapid transit project is slated to debut between 2028 and 2031. If ridership is high enough, the line could be converted to a subway after 2060.

Still, the biggest change in how people move through Los Angeles over the next four decades may not have anything to do with trains. The technology is still in its infancy, but some proponents say autonomous vehicles could significantly reduce car ownership and smooth traffic patterns.

For many commuters, autonomous technology could lower the cost of an Uber-like ride so dramatically that paying to own, park and maintain a private car will no longer make financial sense, said Marques McCammon, general manager of autonomous technology at Wind River, an Intel company.

Autonomous technology could also make other forms of transportation more efficient, allowing buses to run closer together to increase capacity, and making point-to-point shuttles cheaper and more convenient.

Still, most major questions about autonomous vehicles remain unanswered, including when they will arrive in cities, whether consumers will like them, and whether they will complement or compete against mass transit.

Other critics have questioned whether replacing the most painful part of driving — the driving — with time to sleep and work could exacerbate urban sprawl, encouraging residents to eschew dense urban corridors and move farther away from city centers.

What those corridors may look like in several decades is still in question.

Los Angeles is in the midst of a building boom to add more apartments and condos in downtown and other neighborhoods, often near mass transit.

But a group of advocates has sponsored a measure that will appear on the March ballot, aimed at cracking down on so-called mega-developments that they say exacerbate traffic and go against city planning rules.

The proposal would institute a two-year ban on the zoning changes that allow for higher-density construction, which could make future developments more difficult.

In contrast to other major cities, where skyscrapers crowd the skyline, Los Angeles’s future will probably be “a mix of low-density single-family neighborhoods and high-density boulevards,” served by private cars, transit, walking and shared-ride services, said Matute, the UCLA expert.

“It would be a unique L.A. solution to mobility,” Matute said. Although density will increase along major corridors, he said, “I still see the Hollywood Hills looking pretty much how they look now, and people from all over L.A. being able to see them.”

For more transportation news, follow @laura_nelson on Twitter.

ALSO

DA’s office will review campaign contributions from donors with ties to Sea Breeze developer

Southern California’s deadliest quake may have been caused by oil drilling, study says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.