Oakland warehouse had hosted parties, despite safety concerns of former residents

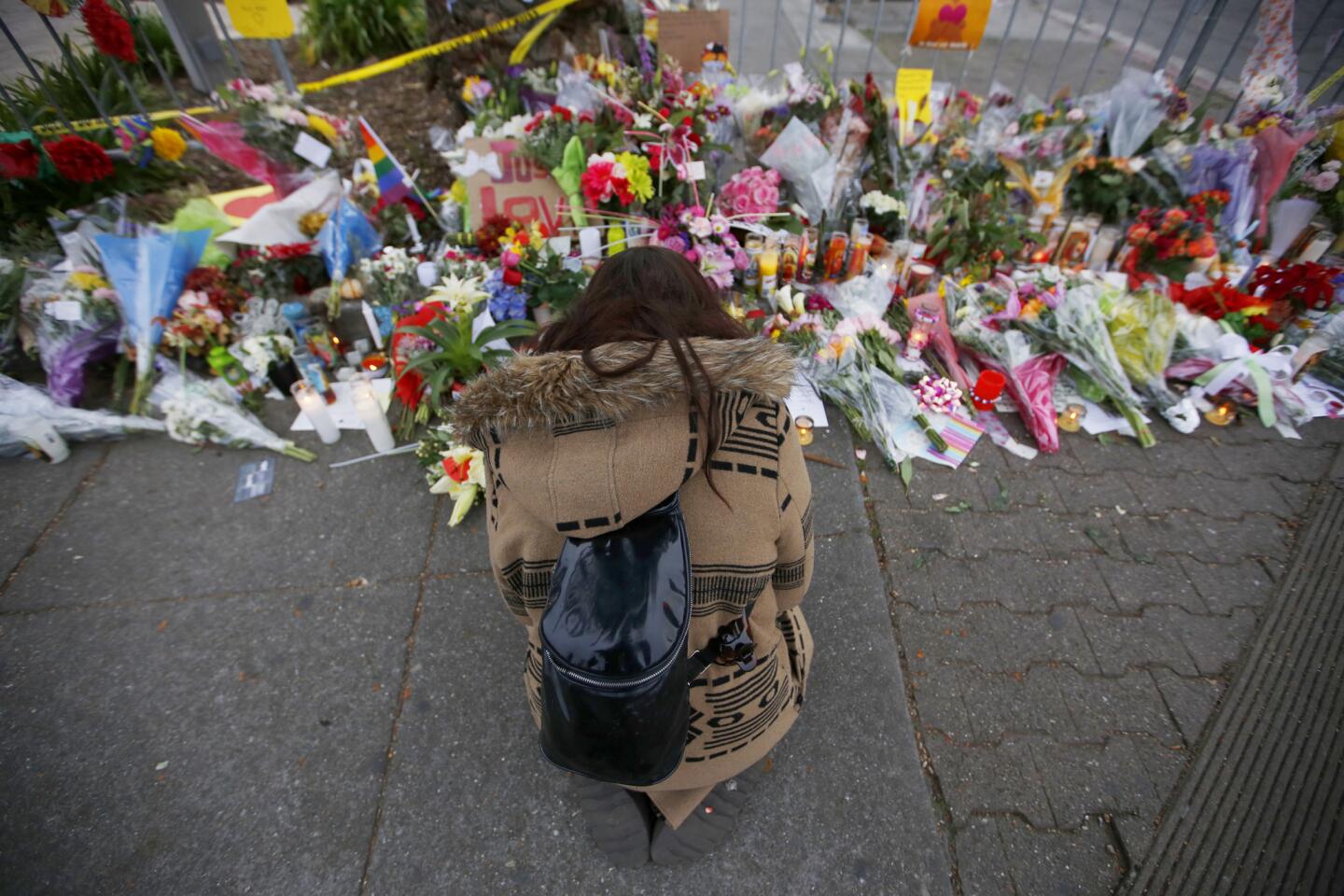

Flowers placed near the site of the Oakland warehouse fire. Video by Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times

- Share via

Reporting from Oakland — They happen all the time, all around the country: unpermitted dance parties put on by artists, promoters and others who bypass official channels to give fans an opportunity to revel in their music.

Often, there isn’t much money to be made. Those involved in the scene can play multiple roles — entrepreneur, performer and host — to make them happen.

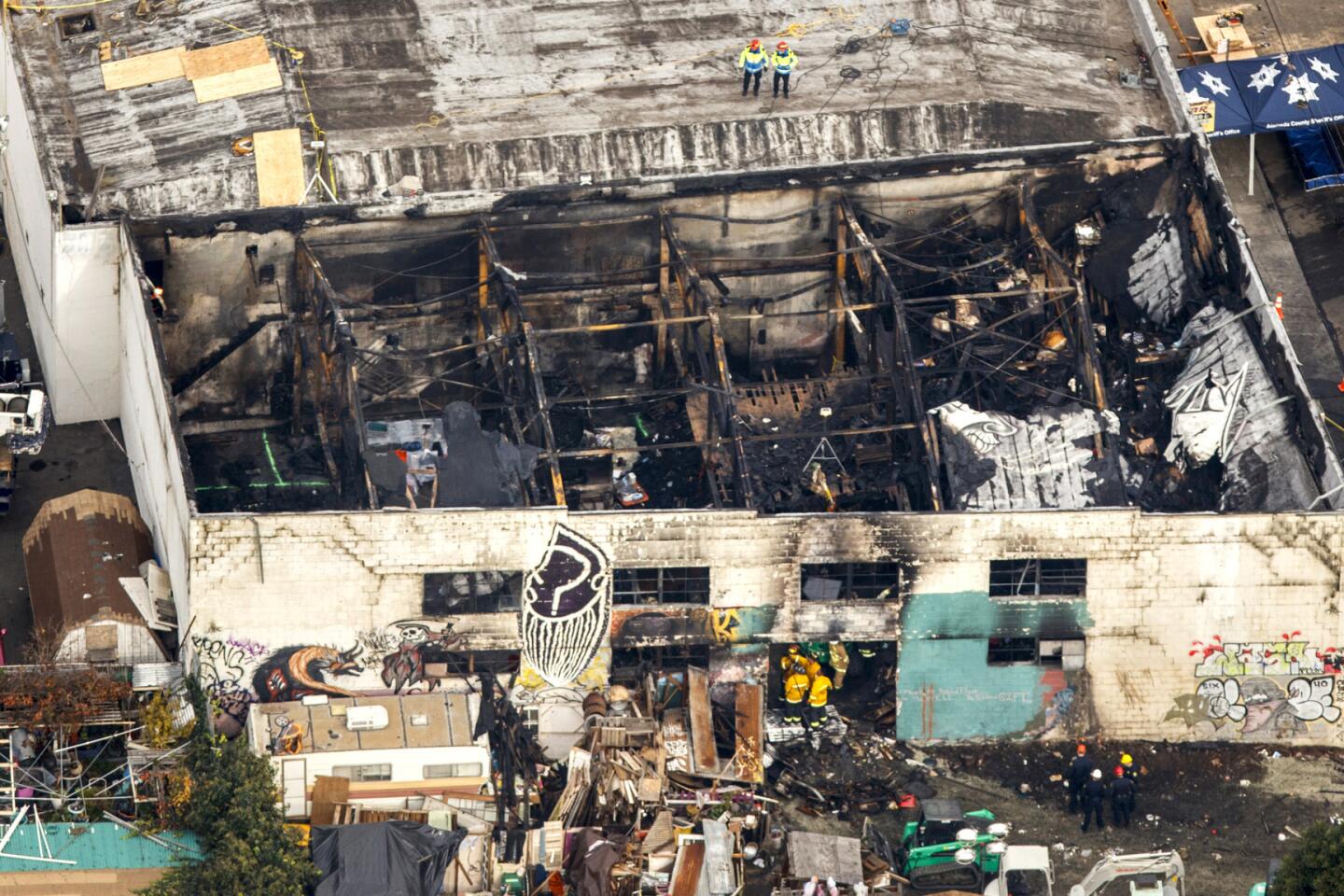

Now, as investigators begin to examine the massive fire at a party in Oakland, which killed at least 33 people, they will try to determine whether anyone was criminally responsible for what happened in the nearly 10,000-square-foot warehouse that former residents say lacked sprinklers and had a staircase partly made of wooden pallets.

The list of those who may have been tied to the building and party is long: There is the group that leased the building, the person who owned it, the people who promoted the concert, the artists who performed and the small, independent record company some of them belonged to.

There are also questions about whether government agencies and inspectors responsible for enforcing rules at such places adequately did their jobs.

A number of artists lived at the warehouse, though it was not permitted for residency, according to a local official and former residents. And whoever organized the party never obtained permits, city officials said.

Neighbors said they had contacted the city about trash and debris piled up outside the warehouse. Inspectors with Oakland’s Planning and Building Department had been investigating an allegation of illegal construction inside the building as well as allegations that people were living there.

The building is owned by Chor N. Ng and leased to an artists’ collective, according to daughter Eva Ng. Two people interviewed by The Times said the artist group, called the Satya Yuga Collective, was managed by Derick Almena, known to the residents as Derick Ion.

Almena 45, and his wife, Micah Allison, 40, lived on the second floor and often hosted concerts on the premise, which was billed as the “Oakland Ghostship.” On their social media sites they posted pictures of mannequins hung upside down, colorful tapestries on the floor and wall, Hindu art, furniture from Almena’s travels to Bali and large, exposed wooden beams throughout.

On the first floor of the factory, a half dozen RVs had been parked to provide living spaces for residents.

Shelley Mack, 58, said she paid $700 a month to live inside a trailer parked in the warehouse from November 2014 to February 2015.

She said she had been drawn to the space by a Craigslist ad that promised cheap living space. Once there, she and several tenants — between 10 and 20, depending on the day — shared a single bathroom. The building had no heat, and in November 2014, a transformer blew, cutting off power.

“There was no electricity, and it was freezing in there,” she said.

Gas-powered generators were used to run small space heaters, and propane tanks placed indoor by the exits fueled other heaters, Mack said.

Police were repeatedly called to the warehouse to address complaints, Mack said. Those reports could not be confirmed to the The Times on Sunday by Oakland police.

Danielle Boudreaux, a former friend of Allison’s who spent time at the warehouse, said there was no hot water and insufficient electric wiring.

After a December 2014 party, one partygoer notified the city fire department of unsafe conditions, and it was inspected, Boudreaux said. She did not know the result.

She said she also tried to alert Almena to the problems.

“I absolutely warned him this place was too dangerous,” said Boudreaux.

Almena did not respond to requests for comment.

“I’m going to have to speak to my lawyers before I answer any questions,” Allison said.

Despite the conditions, the warehouse appears to have frequently hosted parties.

The one that ended in tragedy had been promoted for at least two months, according to various social media posts.

A flier for the party mentioned the Los Angeles-based label 100% Silk and some of its artists as being involved. Twelve individuals were listed as hosts of the party on its Facebook page.

Amanda Brown, a co-owner of 100% Silk, said she doesn’t know who put on the party.

Typically, such concerts are a joint effort with many people involved, including the artists playing at the show and local community members, she said.

“These aren’t people with booking agents,” Brown said. “These are people who are reaching out to the community to see if anyone has a couch they can borrow or a backyard where they can put music equipment.”

Britt Brown, another co-owner of the label, said he didn’t make any money from the event. “We had literally no involvement in it,” he said. “We didn’t get a dollar.”

Often, somebody collects a small fee from people entering a party like the one Friday night, Brown said, but it’s not much, maybe $5. The money would be split between the venue to help pay the electric bill, for example, and the musicians for a little travel money.

Brown said he didn’t know if anyone collected money Friday night. “I don’t know who was putting on the show, I never had heard of the venue space before, I have never been there,” Brown said.

It’s also unclear who made the promotional flier bearing his company’s name. “At this underground level, our label would just sort of be like a flag to rally around,” Brown said. “Several of the artists met by working with our label; it becomes like a little extended family.”

When he was a touring musician, Brown said it probably would not have crossed his mind to ask about safety precautions at a small warehouse party. “Especially if the place had a reputation for hosting events successfully,” he said.

That relaxed attitude might seem dangerous to someone unfamiliar with such informal, underground events, Brown said, “but to us it was just normal.”

David DeMember, a San Fransico Bay-area music industry veteran who founded Raves.com, said he believed Ghostship was a somewhat atypical venue because of the space’s layout.

“I wouldn’t have felt safe there,” DeMember said. “I would have stood near the door.”

While large warehouse parties typically get the necessary permits to hold concerts, smaller underground warehouse parties — like the Ghostship event — typically operate in a DIY style, he said.

Following Friday’s fire, some local promoters were upset about the lack of safety measures at Ghost Ship, DeMember said. He predicted that city officials would crack down on unlicensed venues.

“There’s a strong supportive music scene out here,” DeMember said. “You are already seeing promoters talking about how we have to look out for each other.”

Times staff writer Paul Pringle contributed to this report.

ALSO

Names of seven victims released in Oakland fire; criminal investigators on scene

A woman’s frantic, anguished Facebook search for friend missing in Oakland fire

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.