- Share via

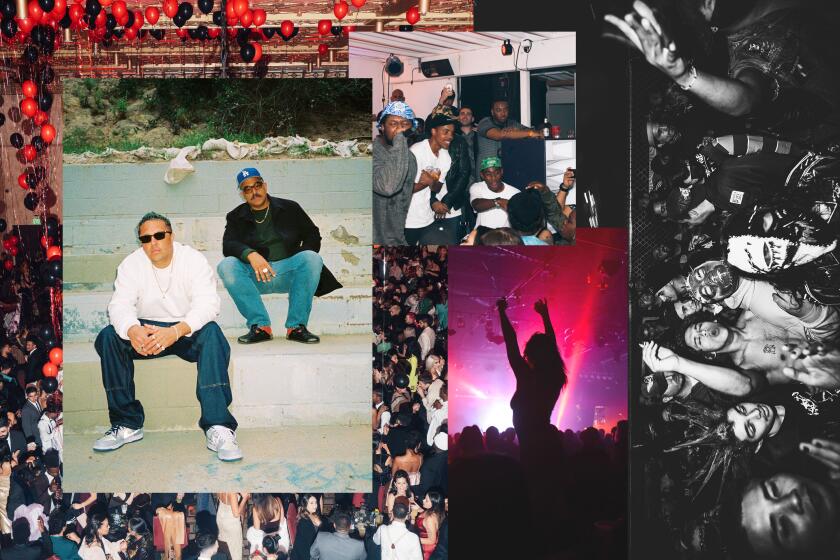

This story is part of Image issue 9, “Function” a sonic and visual reminder that there ain’t no party like an L.A. party. Read the full issue here.

Hana Vu texts me the Monday after I meet up with her at Cafecito Organico, a coffee shop in Silver Lake off Hoover Street. The back patio is where you can find her a few times a week, among the crowd of fellow young caffeinated artists for whom this place is a magnet. When I arrived, Vu was catching up with a friend she ran into.

It was Friday. She was wearing a black tee, a button-up and Doc Martens, with a grown-out shag haircut and no makeup. Up close, Vu looks like she still might be mistaken for someone too young to get into a proper club — she’s 21 — but then, between compulsive drags of her black Juul, she’ll say something like, “Every now and again, you remember that we are literally alone. Everybody operates on their own frequency, and you can never fully harmonize frequencies with any other person because everyone is so infinitely complex.” That night, she’d planned to go to HEAV3N, L.A.’s wild, stylish queer party where drag queen Violet Chachki was set to DJ.

When I ask her how it went, she replies: “Being young is fun and weird.”

The idea that youth is one of the few things in life that’s both terrible and cool at the same time is a central theme in Vu’s world right now. It’s something the L.A. native investigates, both intimately and at an arm’s length, in her debut full-length album, “Public Storage,” and on “Parking Lot,” her recently-released EP that functions as a kind of extended cut — a compilation of songs “that didn’t make it on the record and some live recordings.” (She will perform the new music for the first time on March 31 at the Moroccan Lounge.)

Her first official release with electronic record label Ghostly International, “Public Storage” is a sonic manifestation of the push and pull of young adulthood and the many contradictions that come along with that: caring too much and not at all; navigating the urge to self-deprecate versus having a God complex; thinking about age constantly or resigning yourself to the idea that it doesn’t matter.

In a swift 12 songs and 39 minutes, Vu grapples with what it takes to unmake and remake the self. She attempts to banish versions of herself she doesn’t want to be anymore and will new ones into existence. The most clear example of this tendency toward leaving herself behind in favor of something new is “Maker,” a sweet and sad plea to a seemingly higher power to make her into anybody else, to forgive her for not being stronger or clever enough to know better. “I think that was the core of what I was feeling at the time,” she says. “Like, how do I become something that I want to be? How does anyone become something that they want to be? I just am so not anything that I want right now. That was sort of my thesis statement.”

Performance itself can conjure and mold identity — exchanging the former self for an alter ego or new persona entirely. Vu understands this idea intimately. She delved into it with 2019’s conceptual dual EP “Nicole Kidman / Anne Hathaway,” which explored the way we perform in our day-to-day lives. It’s something she’s been doing onstage and off- for a long time. “I’m really good at performing maturity,” she says. “But I think everyone inside is a baby. Literally, everyone inside is a baby and they just want to cry.”

::

Vu grew up in the San Fernando Valley to “creative-in-a-corporate-way” Gen X parents who encouraged her to pursue her artistic sensibilities. They would eventually divorce, forcing Vu, the oldest of three, to bounce between Sherman Oaks, where her dad lived, and the Hollywood Hills, where her mom moved. It left her feeling unrooted, searching for solace in music and herself. Vu traces her origin story as a musician and performer back to the time at Sherman Oaks Elementary when she was running for class president and gave a speech to her peers. Her teacher lauded her for how clearly she spoke, how commanding her presence was. The validation was intoxicating.

When she started uploading tracks to Bandcamp at 14, and performing in L.A.’s DIY scene not long after, she was driven by this same desire for attention, the desire to be seen. Her first show was at AMPLYFi, a pay-to-play spot on Melrose where “everyone had their first show,” she says. She started working with promoters like Minty Boi Presents, who back then was planted firmly in the indie community and once put on a show that featured Vu performing in a school bus in a parking lot. Other memorable performances include that one time in a freeway underpass near the Arts District, or a house dubbed the Titanic house because of its address: 1912. Downtown’s iconic indie venue the Smell became like a second home, Facebook Events was still a main form of promotion.

“I guess it’s because I’m old now, but I’m like, ‘Where did the teens go now?’ I was out Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday at a random warehouse with only teens — like, 100 teens — not an adult in sight,” Vu says. That energy feels impossible to re-create now, especially since the pandemic. “I always think to myself, the DIY scene is dead. But maybe I’m just old and I’m not there.”

Buy a copy of Function

It’s true what they say: ain’t no party like an L.A. party. Image magazine is back with Issue 9, the first issue of 2022.

Shop the L.A. Times Store

Vu’s early music was both precocious, as you might expect from a young indie rock-pop artist who emerged from the DIY scene, and also disarming. Her contralto felt like sinking into a warm milk bath, or what I imagine a pool of velvet to feel like. Songs like “Crying on the Subway,” off her 2018 EP “How Many Times Have You Driven By,” detailed trying to escape the blues and grays of heartbreak by taking the Red Line downtown.

She sparked comparisons with some of her primary influences, ranging from pop goddesses like Lana Del Rey and Taylor Swift (in honor of whom Vu has a “TS89” tattoo on her right leg) to Angel Olsen and St. Vincent. Pitchfork dubbed her a “prodigy.”

“My whole thing was like, ‘I’m a teenager!’” Vu says, looking back at that time. “Now it’s not that cute anymore. When you’re a teenager, everything you do above the expectation is impressive. But when you’re in your 20s, you stop being amazing.”

She went to North Hollywood High, across from one of the most expensive private schools in the city, Oakwood School. “I went to school across the street from Lily-Rose Depp,” Vu says, “She was at my first show at AMPLYFi with her friends. Like, I don’t think she knew who was playing.” With graduation looming, Vu applied to one school only — New York University, to study at the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music — and got in. She was, admittedly, driven by this recurring need to be the best. “It was more of an ego thing,” she says. “I wanted to have proof that I was better than everyone else. Like when I was a kid, and we were all playing shows and we’re all kind of s—y, but I want to be the best s—y band.”

Vu decided not to go to NYU. This was the last semester of her senior year; she was 17 and had released “Crying on the Subway.” It gained the attention of people in the industry and landed her a deal with Luminelle Recordings, plus an opportunity to tour with indie-pop duo Sales. “I was kind of like … college? I was not committed to that, but I was committed to chilling out.”

Vu was even more committed to her dream of becoming a full-time musician, which was already happening. College was also costly — NYU is among the most expensive schools in the country — so she decided to stay in L.A., moved out on her own and started making music full time. She dealt with all the normal postgrad malaise and the loneliness that comes along with doing the opposite of what your friends are doing. The isolation ultimately would inform her music. “I just spent so much time alone,” she says. “I was always thinking and very much in my head. I’m a very observant person — I’m an Aquarius moon.”

More from The Function

Jason Parham talks to DJ Quik about his legacy

Born X Raised takes you inside the most epic ragers in L.A.

The homies let us know what makes an L.A. party an L.A. party

Gary “Ganas” Garay searches for the forgotten voice of the barrio, Jonny Chingas

San Cha tells Suzy Exposito how she learned to sing from a divine place

::

Vu’s creative process starts with watching reruns of “Mad Men.” There’s something soothing about consuming television she’s consumed more than 100 times before that allows her brain to relax and open itself up to creativity. “It affirms these ideas and characters that I already know within myself,” Vu says. Next, she’ll spend time walking, experiencing, thinking. If there is even a thread of an idea that captures her, she’ll write it down and see where it goes. She writes her songs in pieces, but most of the process is rooted in living life. “I spend like 10% of my time like actually making music and like 90% of my time pondering,” Vu says.

The cover art for “Public Storage” features a closeup shot of the inside of Vu’s mouth with the contrast turned up to 100. The shot was inspired by Bruce Nauman’s “Studies for Holograms.” It’s a gnarly image, an intimate — and literal — look inside of Vu.

The record mirrors that, a meditation on self that’s abrasive and vulnerable at the same time — letting us into Vu’s brain but making no promises that it’ll be pretty. Take “Heaven,” a baroque pop song that grips you with its grand orchestral elements and Vu’s deep wail. It’s about L.A. When she wrote it, Vu was thinking a lot about a meme she saw somewhere on the internet that dubbed New York “fun hell” and L.A. “s—y heaven.” It was deep into the pandemic, and the city was on fire. “Sirens deafen / Everything’s on fire in heaven, heaven,” she sings in what sounds like a moody lullaby. Between the booming drums and guitar on the album’s title track, “Public Storage,” Vu sings about not believing in failure or family, or even magic; in it, she admits, “Every day is the weekend ‘cause I’m vain and conceited.” “World’s Worst” serves as a self-deprecating warning, that she’s the world’s worst color, that she’ll stain your skin.

“Public Storage” was the first time she’d worked with a co-producer, Jackson Phillips of Day Wave. Vu is an artist who has always known what she wants. Working on the album required her to practice relinquishing control. Phillips also served as co-writer on songs like “Maker” and “My House.” “Initially, I think I realized that she really just has a very strong sensibility,” says Phillips. “Everything that she makes is very much her and it’s very distinct. There’s a character to her sensibility that you’re not going to get from anyone else.”

Since the record’s release late last year, Vu has been thinking about a few things more deeply: 1. how productivity is a social construct tied to capitalism, so she really shouldn’t feel as guilty as she does for relaxing. 2. how one’s birthday is quite literally meant for crying. 3. how she can’t help but “kind of hate on” people who come to L.A. from, like, the Midwest in search of fame. 4. how she feels old and young at the same time. 5. how, at their core, everyone is supposed to make art and not send emails.

But the biggest epiphany is that what Vu was trying to figure out with “Public Storage” — an anxious desire to be different, or better, in order to be happy — will never happen. And maybe that was the point all along.

“I’ve just accepted what is going to happen is going to happen, and also it doesn’t matter — and everything matters,” she says. “I was so desperate to get to some sort of place I always wanted to be at. That record sounds very much not at peace. And I feel very at peace the past couple months. I released it all into that record. I’ve said my piece.”