- Share via

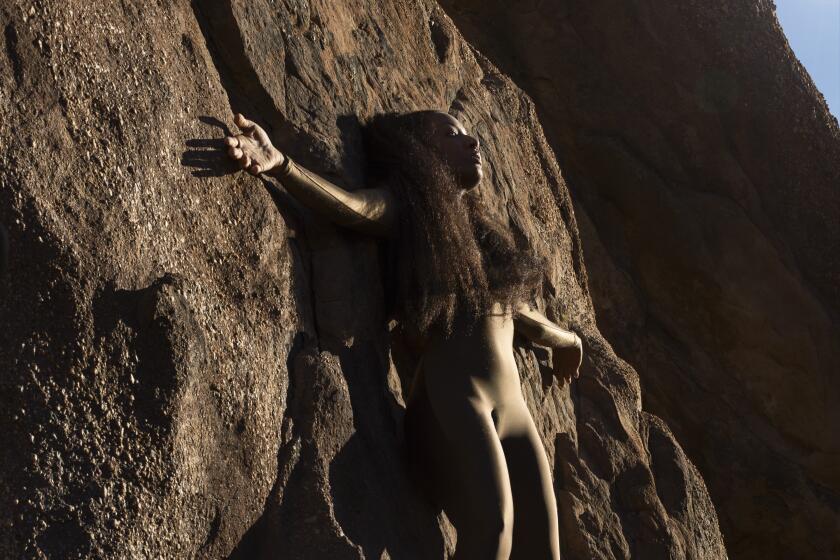

This story is part of Image issue 8, “Deserted,” a supercharged experience of becoming and spiritual renewal. Enjoy the trip! (Wink, wink.) See the full package here.

The world gets smaller, but space goes on forever. My conversations with Grammy-nominated singer Alice Smith attest to this dichotomy. While I’ve been devotedly listening to Alice’s music and bearing witness to her performances since 2009, it’s only been within the past year that the degree of separation between us downsized to none. Her mother connected us after visiting my 2020 museum show at Savannah College of Art and Design with a mutual friend. Ever since, our chats seem to have a similar flow: They begin with things about the body and interiority, then inevitably catapult toward the ephemera of the unknown. Our work, mine as a visual artist and hers in the sonic space, also has that in common. One listen to her ethereal cover of Jalacy “Screamin’ Jay” Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You” or her own “Something” crescendos into a realm beyond the reach of language.

Last month we met up in the Mojave desert, perfectly timed by Alice to align with the full moon and lunar eclipse. The vivid expanse of the desert landscape collaborated in all the synchronicity that we felt that weekend. Joined by her homegirl Hopi, we ventured over to the Integatron and seized the last three spots of a sound bath session. We emerged feeling supercharged as we unpacked our experience with a heightened awareness of our connection in all directions — from person to person, horizon to horizon, from ground to the celestial realm.

Kenturah Davis: We’re here in Joshua Tree. We had a moment together experiencing the full moon, and it actually eclipsed. We sat outside. We did a sort of ritual where we wrote the negative things we wanted to release down on paper and burned it. Then with our words we spoke to the positive things that we wanted to attract. It was a really beautiful moment.

Alice Smith: Then the next day we got a massage. Self-care under the light of the moon and the sun. In the company of the Joshua trees and the rocks of hills that looked like they were intentionally placed there on purpose.

Inside issue 8: ‘Deserted’

Sophia Nahli Allison shows you what’s possible when you allow yourself to be led by spirit.

Justin Torres remembers those visits to the clothing-optional hotels in Palm Springs.

Julissa James explores why so many people head to Joshua Tree to do shrooms.

Dave Schilling gets to the bottom of why chest hair is the desert’s No. 1 accessory of choice.

KD: As a person who doesn’t come out here all the time, I think the draw is this kind of expansive landscape. The horizontal and the vertical. How did you feel looking at the sunset?

AS: It’s so pretty. I think sunsets just make you feel connected to it all. You’re in it. Being in places like this, where you’re actually able to really see the world makes you feel like you’re part of it a little more, like when you sit in front of the ocean. It’s out there in front of you. And you’re like, I’m on planet Earth.

KD: We also visited the Integratron sound bath. One thing I remember feeling was that we were going through a kind of journey through phases. Can you talk more in detail about what you recall? Like how the phases changed over the 40 or so minutes?

AS: One thing I noticed is that it moved from one side of my body to the other. It moved from my right ear to my left ear. I loved it. My favorite thing was the bi-neural beats thing. It felt like a brain massage.

KD: Throbbing isn’t the right word...

AS: It was pulsing, flexing, vibrational.

KD: My mind kept going everywhere initially. And I kept trying to reel it back in. For the first half of it, the sound was just in my head. And I wanted to feel it moving into my body. When I started to relax more and really tried to stay in the moment more, then I felt the sound sort of move through my entire body, head to toe.

AS: I had a little sadness. I had a little emotional thing. Like when you’ve been holding your breath and you just let it happen a little. I felt a little something.

KD: You’re a sonic artist. You walk around with your gift. Do you think of your own sound — the sound that comes from your voice — as healing?

AS: I’ve never ever thought about it. But I think it probably can be, yes. The making of the sound is healing for me. That’s what I felt like it definitely does. It opens you up.

KD: That’s really interesting. Something that I’ve heard you say is that the voice is different than the song. I wonder if there’s part of your process as a creator of sound that comes before you put words to it?

AS: Yes, there is a part of it that comes before the words. A lot of times when I make things, it’s just the melody. There’s the pattern, then I just sing the melody [breaks into song]: Ooooaahhhhhaaa. And then something usually comes out of that melody. For me, it’s completely abstract. I hear this melody over and over again, and words just start to come. I don’t know how.

The making of the sound is healing for me. That’s what I felt like it definitely does. It opens you up.

— Alice Smith

I always try to record everything I do. If I start to feel like I’m gonna start singing, I record. I come up with a lot of stuff in the shower. I hear some words, and then I record it, and then we listen back. And you do that until that feeling goes away — until you’re ready to stop.

Sometimes it’s just a question of really liking a melody enough to keep singing it. And then you start to basically plug in, in the phonetics. It’s just phonetics, vowels in a rhythm. It’s like a little puzzle. However much comes out is however much comes: You get just a little bit, you get a verse, you get a whole pattern. And then after a little while, then you started to be like, “Well, what’s this really about? All this stuff is really coming to me. What’s it really about?”

KD: When I am going through sounds that might be healing, oftentimes it’s the unspoken parts of sound that might do the most work.

AS: Any sound that’s in nature is a natural sound and is gonna be pretty healing.

KD: What other sounds do you find healing for yourself? Apart from your own voice.

AS: I like the sound of the ocean. I like the sound of wind in the trees.

KD: Your song “Desert Song” has that healing quality. I went back and listened and read the lyrics again — the whole song has an urgency. There is this part where you sing that your mama says, “Sometimes you have to reinvent yourself.” Do you see yourself in a phase of reinvention now?

AS: I guess so. I don’t know if I would call it a reinvention. It’s definitely a redirection. I’m not trying to start over…

KD: Like an expansion…

AS: Yes.

KD: A few years ago, you said you really started to see yourself as an artist. What kind of space were you in when you began to see yourself in this way?

AS: I don’t know honestly. I don’t know what I was doing. Maybe it was that I was getting more information. Maybe it was an over-time kind of thing. Maybe I was spending more time with other kinds of artists, like Khalil [Joseph]. Having had the type of experience with the music business in the industry, I had this realization that people who are not artists — it’s just a different kind of brain. The people who actually run it have not an artistic bone in their body. Having conversations with those people as an artist becomes frustrating because they’re handling your art. They don’t get it. I had to understand that I was different, and really accept that a fundamental difference exists. Art is a fundamental thing. Creativity is a fundamental thing.

KD: I love seeing the expansion. Back to our experience in the desert: I have always thought of the desert as like a site to escape for isolation and recalibration. But you once suggested the significance of community in that kind of landscape. Even if only to feel safe as a Black woman. I was thinking about how that trip with you emphasized sisterhood for me and how that supports survival. Broadly speaking, what does sisterhood and family mean for you creatively?

AS: The support part is invaluable. My friends — they happen to be creative people, whether they use their creativity in some kind of art or not. They’re creative thinkers, creative people. We just connect on a person level. And that level seems important.

KD: I had the very special and unique opportunity to experience you recording some new music with Syience called “Star Wars.” And he said something to the effect of, “When you’re lost in outer space, it’s love that brings you back.” After hearing you lay the vocals I could not stop thinking about it for days, and I still think about it. Can you talk a little bit maybe about love and making music about it and how that connects with the cosmos?

AS: [Laughs while singing “Star Wars” theme] Well, it’s all about connection. At the end, that’s what love is — connection. It’s the thing that connects us. And if we are connected, and we all know that we’re connected — we’re all connected. I mean, just like the little mushrooms and trees in the forest. This is connected to this. That is connected to that. Call it love. Call it whatever you want. “Star Wars” is the name of that song. But I wrote that song in communication with my grandmother. That hit the cosmos.

KD: There’s a deep love there.

AS: That’s a deep love connection. That’s a cellular connection. That’s what I’ll say about that.

Photographed at Planar Pavilions at A-Z West, courtesy of Andrea Zittel and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Kenturah Davis is an L.A.-based artist who is trying to keep cursive alive. Her solo show “apropos of air” is at Matthew Brown Los Angeles through Dec. 18. Her work also is included in “Black American Portraits,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through April 17. Sometimes, she works in Accra, Ghana.