- Share via

1

(Lauren West / For The Times)

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future. See the full package here.

I remember the tears. Not the anguished look on Tre’s face as he yelled for Ricky to run. Not the gunshots, the way they sounded like thunder and slaughter. Not the pool of blood. Or the fear of the moment, and how suffocating that fear felt for the two of them, knowing it was already over. Not the way Tre sweetly cradled Ricky’s limp, lifeless body in the alleyway. What I remember most vividly are the tears and what seeing Tre cry did to me, the despair and defenselessness crinkled into his face, how it stirred something deep inside and suggested, even in that moment of grief, the possibility of the self.

This happened in the years following my parents’ divorce, when we lived on 58th Place and La Tijera, when it was just the three of us, my mom, older brother and I. To that point in my life, at the age when I could finally watch “Boyz N the Hood,” I wasn’t privy to all the ways Black masculinity could sculpt itself. I’d never seen another Black boy cry like that onscreen, unshielded and so completely broken. I was 12, maybe 13, and I didn’t yet understand how sorrow and loss and rage open the soul, how those sensations, pinballing off one another, give way to something transcendent, something essential to our survival, to our becoming.

Justin Torres reflects on what happens when the one thing you’ve never lost finally disappears

John Singleton knew. The filmmaker, who died in April 2019 at 51, understood the power and rhapsody of self-invention, and how important it was to have witnesses. For me, watching “Boyz” made plain how other Black boys could wear their vulnerability. How they could style it, make it theirs. Singleton knew that to be Black in America is to live at the end of a sharp reality: the proximity of our dreaming and our death were ever entwined. Our living — as Black and not yet free — was not divisible from the terror of the white world and the effects those constraints had on us. Singleton was wise to it all. Then again, how could he not be? He was from the same neighborhood as Tre and Ricky. The realities all lived side by side in his searching eyes.

A screenwriter, director and producer of spellbinding talent, Singleton was a custodian of working-class Black life in South L.A. His films were known for attitude and realism but what was special about them, what has given them the stamina to endure across generations, is their openness to feel and be felt. The great misconception about Singleton’s singular body of work, especially his abiding ’hood triptych — “Boyz N the Hood” (1991), “Poetic Justice” (1993) and “Baby Boy” (2001) — was that his movies were hard and unflinching in their portrayal of Black Los Angeles, which they were, but really, in their marrow, what they are about is our fundamental human enterprise: the grace of feeling.

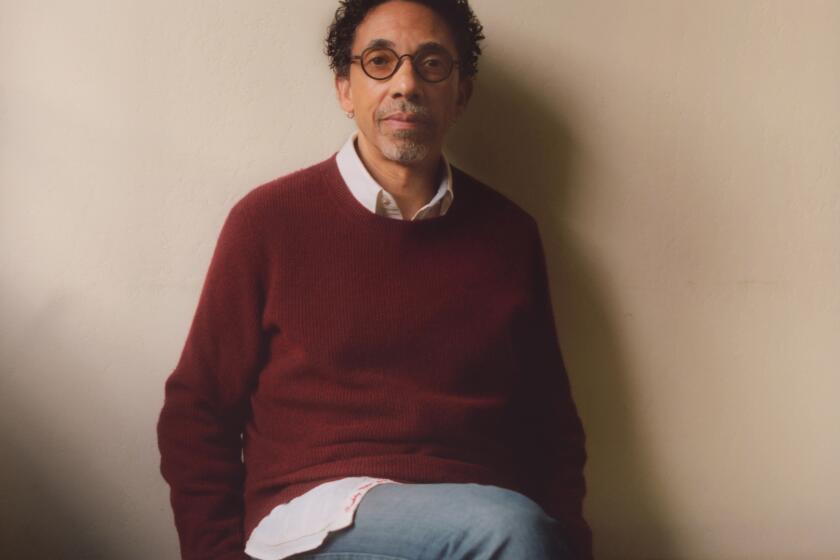

(Los Angeles Film Festival)

That scene in the alleyway, the film’s fatal climax, is not the first time Tre cries. Played with spark and candied charm by a young Cuba Gooding Jr., teenage Tre, like so many other Black boys in that formative season of their lives, is impatient for adulthood. He wants to be a man but doesn’t yet know what it takes to get there, and all that comes with it. So Tre armors himself, he goes about making himself indestructible. He wears his masculinity like he does his clothing. With a fresh fade in denim-on-denim or in a suave black-and-yellow rayon shirt, Tre glamorizes himself as anxious teenagers often do: boldly, loudly. Like all of us at that age, he wants to be heard. “A lot of the experiences come from John Singleton’s personal experiences,” Gooding told The Times in 1991 just as the film was released. “We show it, keep it real and true to life.”

Where another screenwriter might be content with offering his audience a less nuanced side of Tre, Singleton knew better. He had a canny sense for range, and just how much his proudly Black characters could encompass — there was no limit, really — allowing for both Tre’s toughness and the softer parts of what makes a boy a man. In the South L.A. of Singleton’s youth, where social problems defined so much of how Black people wore their identity when they left the refuge of their homes, Black boys were not always given the benefit of their emotions. They weren’t allowed to feel, because feeling was weakness, and being weak made you prey. It got you shot. In an unsympathetic world, survival was paramount. Yet the boys of Singleton’s films were more than the fiction of their bodies, more than the lies that made them targets — he gave them tenderness as a weapon too.

Infused within Singleton’s panoramic Black world were Black boys with the kind of fullness that I was discovering in myself. Just past the film’s halfway mark, Tre visits his girlfriend, Brandi (Nia Long). He’s running late, and by the time he arrives at her doorstep in a black varsity jacket and gray Georgetown Hoyas T-shirt, something in him has shifted. He’s somber and evasive at first, having decided to not tell her that he was just stopped by the LAPD, that he had a gun jammed in his neck, how he thought he might die over some nothing bullshit. Outside, the racket of police helicopters swoop and bang overhead and stray shots pop in the distance. It’s becoming too much, the heaviness of it — and Tre breaks. “I’m sick of this shit,” he says, punching the air with justifiable wrath, “I’m tired of this shit.” He falls to his knees, weeping. When Tre admits embarrassment for his eruption, for the tears, Brandi extends compassion and space. “You can cry in front of me,” she tells him.

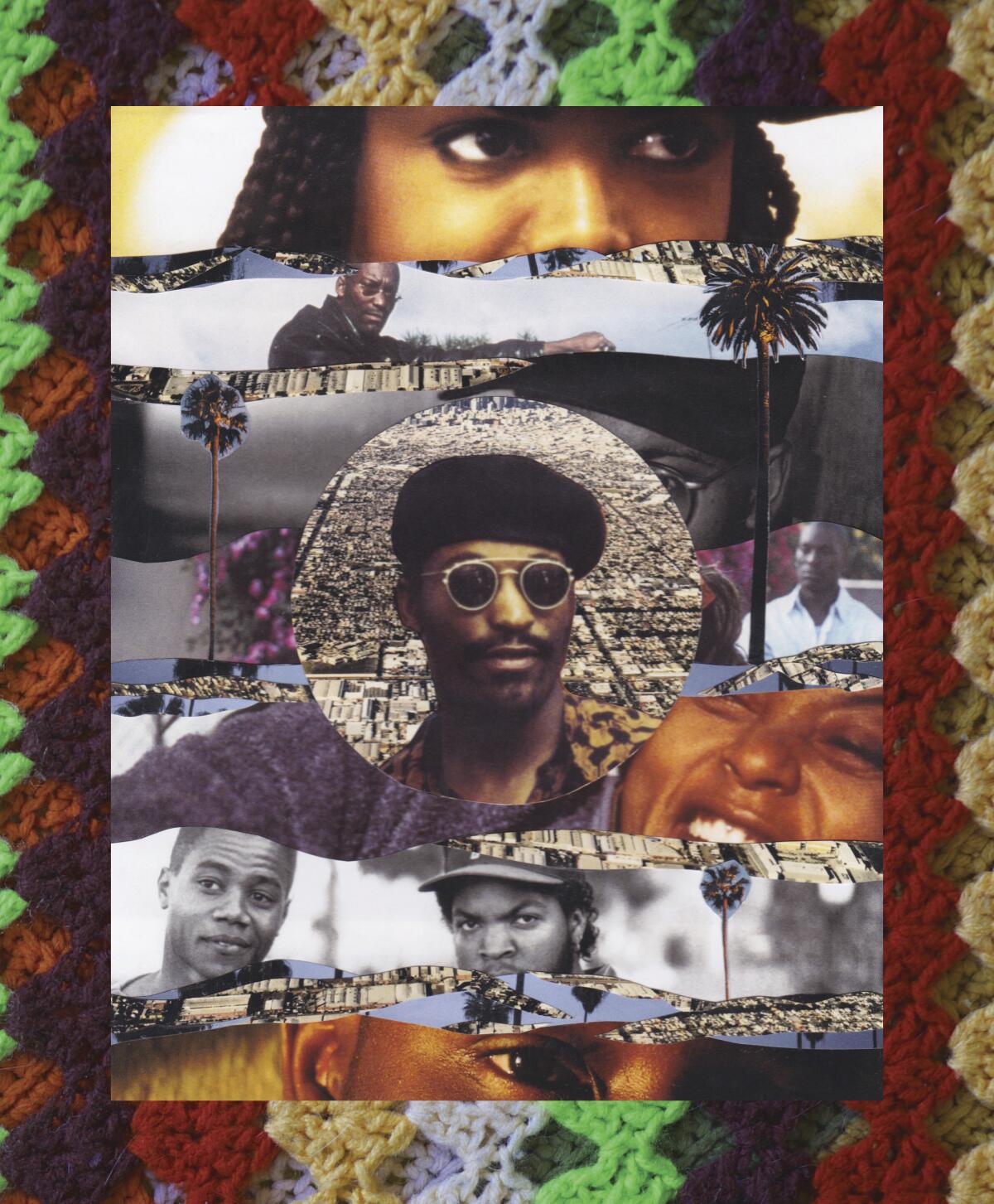

(Photo by Courtesy Columbia Pictures/Getty Images)

That was the genius of a Singleton scene: Between the heat of two characters, how in watching them work, there manifested an unfiltered genuineness of experience. It was authoritative. It was true. I’ve watched that scene a dozen times in the years since, and every time, like the very first time, I’m pulled in all over again. It’s all there in Tre’s face — the look. It wasn’t simply that I recognized a piece of me, it was all the other, less confident selves I realized I could reach for, the vulnerable parts.

In Singleton’s movies, hard men were made soft, but softness wasn’t weakness — it was a form of earned strength. I sometimes wonder if his were portraits given to us in reverse. The white world told us we were one thing. Singleton showed another. In Doughboy (a savvy Ice Cube in one of his earliest roles) and, later, with Lucky (2Pac as the devoted rapper-postman in his sophomore road epic “Poetic Justice”), Singleton revealed how Black boys had been debased and exoticized, which is to say how they had been looked down upon and assumed the worst of. But he didn’t stop there. He knew there was more to the story. In fact, he knew there was an entirely different one to tell. Through them and others, like the man-child Jody (Tyrese Gibson) in Singleton’s midcareer masterpiece “Baby Boy,” their masculinity was given the benefit of their emotions — tested, split open and miraculously remade. He gave us heroes and hustlers who were complex and intelligent and empathetic and bravely cool. In every way, Singleton’s boys gave us another reason to look. To stop and stare. To crush on and obsess over. To mimic, shadow, become.

Witnessing all of that does something to you. It certainly did for me. Singleton’s films may swagger with color and sound but what they teach us, if one pays close enough attention, is that Blackness is a generative practice — that among the despair and constraints the white world forces Black people to live within, and that we so desperately try to break loose from, there is light, there is community and love, there are reasons to keep going. That we can still find a way.

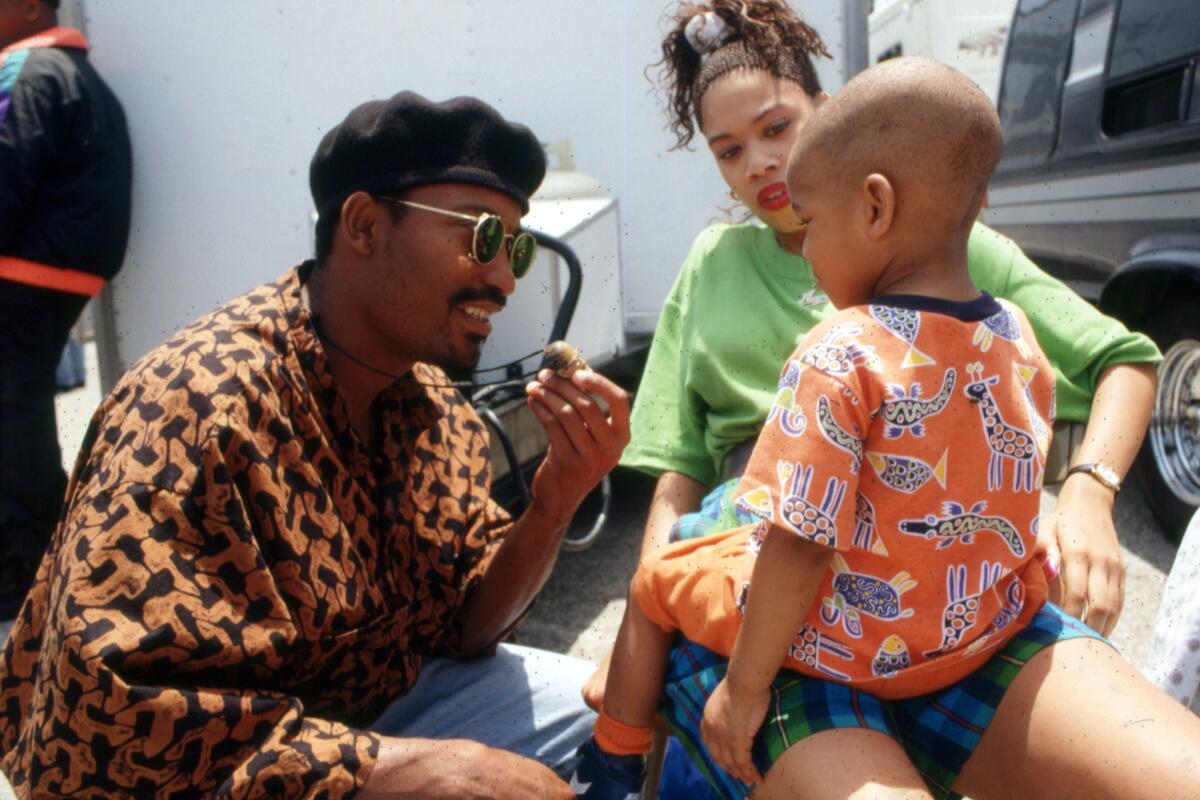

(Photo by Anthony Barboza/Getty Images)

Exactly how did that way manifest through Singleton’s lens? It was the snap and sizzle of dice against a Leimert Park sidewalk. It’s Reva asking, “How you doing?” and Furious responding, “I’m living, that’s enough for me.” It’s the smack of dominoes hitting the table, or a chorus of elder-sisters holding court at a family reunion. It’s a speech about “guns and butta,” a gangster-turned-businessman’s ultimate metaphor for survival. I’m thinking also of the generous vision of brotherhood Singleton rendered in Jody and Sweetpea (Omar Gooding), how perhaps, being a witness to that, a bond whose power was sourced in its tenderness, even as they concealed it in a kind of chest-thumping hardness, showed me another way I could mold myself. Singleton gave our rhyme reason and made our reason rhyme. Still, it is not enough to call his films beautiful or real, because to present Black life with such care and regard as Singleton did was to experience something beyond the realm of beauty or realness — it was to encounter the profound.

John Singleton gave his characters space. But the space wasn’t theirs alone to step into — it was so boys like me could also enter into that bright corridor between who we were and who we were capable of being. He would go on to uniquely chronicle Black L.A., ranking among hometown greats like Wanda Coleman and DJ Quik, but the nectar of his movies could always be found in those moments of emotional shattering. Because it was never about Tre’s toughness. It is his vulnerability that endures.

Jason Parham is the founder of literary journal Spook and a senior writer at Wired, where he covers pop culture.