- Share via

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future. See the full package here.

Los Angeles is a hat town. We are a city both blessed and cursed by the incessant, piercing golden rays that Angelenos cheerfully refer to as “sunshine.” Unless you want to become an everyday umbrella person (which I am always threatening to be), hats are the best option for protection.

Hats are also a way to differentiate yourself. On the Eastside, north of the 10, what you wear on your head is taken to an extreme. It’s here that the floppy-brimmed hat first flowered in Los Angeles during the fleeting era of the Nasty Gal. You can still see a fedora in Hollywood, Santa Monica or really any place that attracts tourists. I think I see a bucket hat every minute, like intermission at the New Radicals inauguration reunion concert.

However, the most striking hat trend right now might be the least practical of them all: the beret. The reopening of outdoor dining in the city was just the thing people needed to don their berets at the Black Cat or Figaro Bistrot. The thick, wool, brimless cap offers no protection from the sun, unless you’re Michael Jordan in “The Last Dance” and you’re totally bald. A beret juts out awkwardly from the head, rising like a soufflé from your skull. Often, it conjures up the buffoonish image of Clark Griswold stumbling through Paris in Amy Heckerling’s “National Lampoon’s European Vacation.” It looks foolish, and — like so many hats that have come to define a nation’s image (sombreros, cowboy hats, ushankas)—the beret is the sartorial choice that invites both sideways glances and accusations of cultural appropriation.

I thought I remembered why I didn’t get cast in “Gossip Girl.” But the truth was much more complicated.

One explanation for why the beret brings about such intense feelings is because it immediately evokes two conflicting ideas: high status and revolutionary fervor. The trend makes room for both the luxurious (a felt Gucci number will cost you $430) and the mundane (an online army surplus store offers a beret for $13.99). The Parisian beret can confer sophistication, class and artistic ambition upon its wearer. The beret is both bohemian and genteel at the same time. Coco Chanel wore a beret but so did Rembrandt, or at least so I have been told. (Because he lived in a pre-IG world, I can’t speak to if he bricked the fit.)

Unfortunately, the beret can also be the refuge of the try-too-hard, the “Emily in Paris” who wants to be someone else. “Ah yes, I will take a croissant. No wait! Make that the pain au jambon, please,” you say as you take the last drag of your clove cigarette. At Tartine in Silver Lake, asking for the “ham and cheese croissant” simply won’t do. When I pay a visit to Echo Park institution Taix, if I’m going to order a socially distanced moules marinière, I just grunt through my mask in the general vicinity of that part of the menu and they get it, but that’s only because they’ve been tolerating poor pronunciation for 90 years.

That feeling of being out of place when ordering breakfast is what wearing a beret for the first time feels like, but it doesn’t have to. A sense of purpose, coordination and confidence can make even the most outre fashion decision seem appropriate. Shame simply has no place in the lexicon of a stylish person, and anyone wearing a beret should do so with aplomb. Embarrassment is an illusion perpetuated by people with no taste to make the world worse.

While the beret has a surplus of bourgeois connotations thanks to the social climbers of Los Feliz and East Hollywood, it’s also a globally recognized symbol of revolution and social change. When “Lovecraft Country” star Jonathan Majors paired a Stussy Dior beret with an upraised fist on the cover of the September issue of GQ, it said something: a Black man exuding power and defiance during tumultuous times. The beret took on that meaning thanks to the French Resistance during World War II, Che Guevara and, of course, the Black Panther Party. The Panthers, dramatized in Shaka King’s film “Judas and the Black Messiah,” used the beret as a way to connect the Black American liberation movement to the lineage of revolutions around the world.

Locally, the Brown Berets, an antifascist Chicano movement in the late 1960s, took direct action against police brutality in East Los Angeles wearing theirs — no wonder they joined Panther Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition in 1969. The Rainbow Coalition attempted to unite socialist organizations throughout the United States to work together to lift Black people and other people of color out of poverty. If style is defined as the free expression of ideology, class and individuality, then the beret is the ultimate mixed message — both a symbol of the status quo and a call to action.

The beret is the perfect affectation for the searcher, the seeker and the student. As a symbol that straddles both sides of the widening class divide in Los Angeles, the beret holds a particular fascination here, and especially in neighborhoods like Silver Lake. As Sunset Boulevard continues to swallow up legacy businesses and replace them with middlebrow fashion like the French Maison Kitsuné outpost that just opened up two blocks from the 99 Cents Only Store — and, on Tuesdays and Saturdays, the farmers market — the beret, like the neighborhood itself, can go either way. We could either choose to dedicate ourselves to uplifting our neighbors and building a more equitable and empathetic city or we can order another croissant.

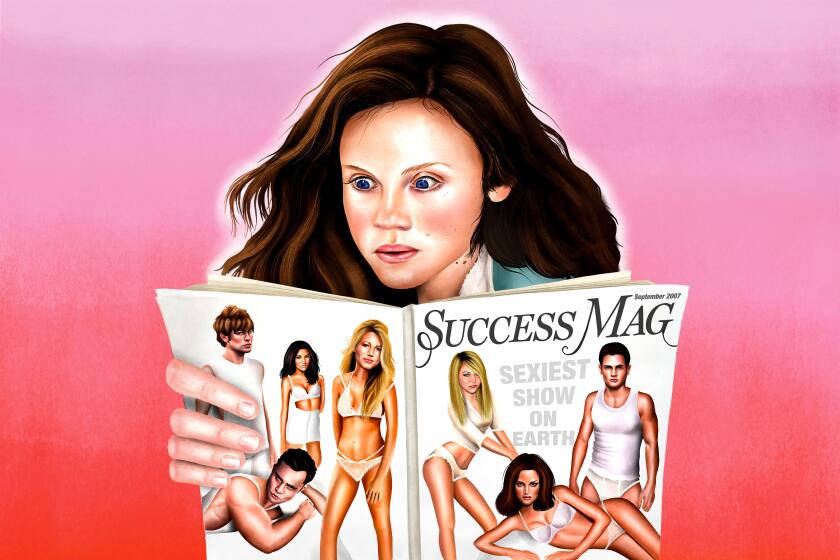

For inspiration, I suggest we look to that great fictional Southern California icon and beret wearer Cher Horowitz, the protagonist of Amy Heckerling’s other masterpiece, “Clueless.” Cher was no revolutionary, but her beret signified to the audience — or at least the students of Bronson Alcott High School — that this seemingly shallow young girl was open to change, that she wanted to learn and that, soon enough, she’d see there was more to life than the perfect world she inherited.

Dave Schilling is a writer, humorist and appreciator of fashion whose work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Guardian, New York Magazine and GQ.