Coming soon in the medical arsenal against cancer: vaccines

It’s a deceptively simple idea: What if doctors could recruit the body’s own immune system to fight cancer? The complexities of the immune system have kept this from becoming reality, until now. Three cancer vaccines -- for prostate cancer, melanoma and lymphoma -- have achieved positive results in so-called Phase 3 clinical trials -- the kind of studies that the Food and Drug Administration requires for a medicine to gain approval.

At the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology held May 29 to June 2, researchers reported that a vaccine against follicular lymphoma, called BiovaxID, delayed remission after chemotherapy by more than one year, on average.

At the same meeting, other researchers said that a melanoma vaccine caused tumors to shrink in twice as many patients as those receiving a standard FDA-approved therapy.

And at the annual meeting of the American Urological Assn. in April, researchers reported that the vaccine Provenge extended the lives of men with metastatic prostate cancer by four months, on average.

Doctors are cautiously optimistic about the news. “Researchers have been working very hard to get some positive results,” says Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta. “These three trials do suggest that vaccines will be used in the actual treatment of patients in the not too distant future.”

But even with these tentative successes, a big question remains open: Will vaccines ever become more than small players in the medical treatment of cancer -- a group of diseases that presently kills some 560,000 Americans each year?

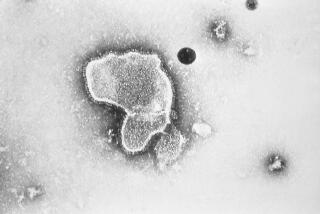

Only two cancer vaccines currently have FDA approval and both are strictly preventive, targeting viruses that can lead to cancer. Most U.S. children are vaccinated against hepatitis B, a virus that can cause liver disease and cancer. A vaccine for genital human papillomavirus (HPV), which can cause genital warts and cervical cancer, is now recommended for adolescent girls.

The new medicines -- called therapeutic cancer vaccines -- act differently. They are not preventive in the traditional concept of vaccines. Rather, patients already afflicted with cancer are vaccinated in the hope that the shots will tell their immune systems how better to fight growing tumors. And because the immune system has a long memory, it’s hoped that this immune boost might also ward off cancer recurrences.

Researchers have been working on the strategy for at least four decades and have suffered many failures, even in vaccines that showed promise in Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials, which test safety and effectiveness of experimental treatments in a small number of patients. “It’s been a really frustrating journey for a lot of researchers,” Lichtenfeld says. “A lot of hope and a lot of dashed hopes, unfortunately.”

Basic research on the immune system in the last 10 to 15 years has led to an explosion of new knowledge about the intricacies of the immune system -- and some clues as to why these early strategies failed. For instance, it’s now known that tumors can shut down immune activity in their vicinity. The three new vaccines, as well as many more under development, have incorporated past lessons and new knowledge to improve their odds.

Generally, vaccines are made from a substance that only cancer cells make (or that they make far more of than normal cells do) -- say, a protein that sits on the surface of a tumor cell. Then the vaccine is injected into the body. If the immune system senses that the substance is a foreign invader, then it starts to ramp up a response. The mechanisms vary, but essentially the body makes new immune cells and sends them out on search-and-destroy missions, seeking out anything that contains that same substance, or marker.

In the past, small protein fragments -- called antigens -- that are present in high amounts on cancer cells were used in cancer vaccines. But the ones that were chosen did not stimulate enough of an immune response to attack tumors effectively.

“We know a lot about tumor antigens,” says Dr. Leisha Emens, an oncologist at Johns Hopkins University who is researching breast cancer vaccines. “I don’t think we’ve done that great of a job identifying which ones are the most important.”

You don’t want just any immune response, you want one that will effectively attack the cancer cells, she says.

Dr. Donald Morton, chief of the melanoma program at the John Wayne Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, tells a cautionary tale. He led a different melanoma vaccine all the way through to a Phase 3 clinical trial. With 1,600 patients worldwide, it was much larger than the recent crop of studies. Morton says the rate of survival in the study was the highest he’d ever seen. However, that rate did not differ from the control group, who received only an immune stimulant, and the trial was halted in 2006. “There’s no question that some patients responded to the vaccine,” he says, based on a review of the data. However, many more patients did not.

The three vaccines with recent success don’t work in all patients either, even though researchers tried to define patient populations that would be most amenable to vaccine therapy. In the melanoma vaccine trial, only patients with certain tissue types -- akin to tissue-typing for organ transplantation -- were included.

In the lymphoma vaccine trial, only patients who responded to chemotherapy and remained in remission for six months were eligible to receive the vaccine.

The vaccines don’t measure up to other cancer therapies that have passed muster with the FDA in recent years, such as Herceptin, Gleevec and Rituxan, says Dr. John Glaspy, director of the Women’s Cancers Program at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. Gleevec, in particular, has revolutionized the care of the most common adult leukemia, known as chronic myeloid leukemia, raising five-year survival rates to 89% of patients taking the drug. Before Gleevec, patients’ chances of surviving for five years with existing treatments were closer to 50%. “Those are huge breakthroughs in oncology that have made big impacts,” Glaspy says.

Cancer vaccines have made comparable advances on the basic science front, but they have not yet translated into successful medicines. Yet researchers are reinvigorated by the recent successes because they suggest that, with combination therapies and careful patient selection, the vaccine strategy could work to fight cancer. “It’s feasible,” Glaspy says. “We’re starting to see a few patients do well.”

The ideal of therapeutic cancer vaccines still shimmers with promise: Imagine a medicine that’s specific to a tumor and free of side effects. “If we can get the immune system to engage in this process, it works completely differently than any other cancer treatment out there. And the neat thing about the immune system is that it remembers,” Emens says. “If we can get it to work, it has the potential to add a lot.”

Even those stung with failure hold onto hope. “I remained convinced that the immune system is very important in the control of cancer,” Morton says. “We just need to know what the right buttons are to push so that everybody responds.”

--