- Share via

Current plans for reducing water use along the Colorado River should be sufficient to stave off the risk of reservoirs reaching critically low levels over the next three years, according to a new analysis by the federal government.

The Biden administration announced the results of its analysis Wednesday, indicating that cuts in water use pledged earlier this year by California, Arizona and Nevada are likely to ease the threat of reservoirs declining to perilous lows — at least in the short term.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation cited the wet year and the above-average snowpack in the Rocky Mountains as a key factor that has helped reduce the risk of a crash in supplies between now and the end of 2026, when the current rules for dealing with shortages expire.

The three states in May committed to reducing water use by 3 million acre-feet over three years, cutting usage by about 14% across the Southwest. Federal officials said those voluntary conservation efforts, largely supported by federal funds, allow the region to discuss new long-term rules for managing the river over the next two decades.

“We’re already seeing the success of our work on the voluntary conservation measures,” Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton said. “It’s helping to stabilize the system for now, but also allows for a path to talk about sustainability for the future.”

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

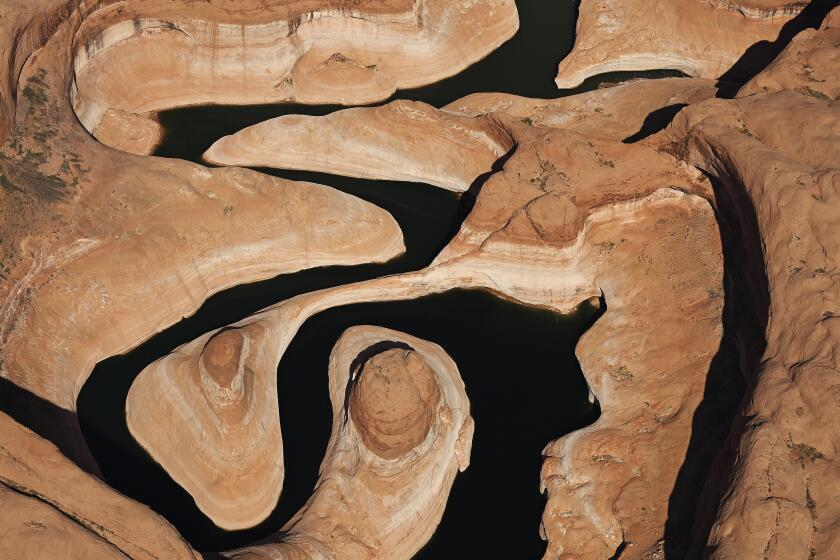

The Colorado River’s two largest reservoirs remain at low levels, even after rising with runoff from this year’s snowpack. Lake Mead is now 34% full, while Lake Powell sits at 37% of capacity.

Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said the ongoing conservation efforts by states in the Colorado River Basin have helped ease the immediate risk of reservoirs “falling to critically low elevations that would threaten water deliveries and power production.”

The federal government analyzed the water-saving agreement proposed by the states as part of a review focused on updating river management rules for the next three years.

Federal officials conducted a modeling analysis based on the latest hydrologic data and found that the states’ water-saving proposal, when compared with other alternatives or taking no action, would reduce the risk of reservoirs declining to critically low levels.

Based on these findings, officials designated the states’ plan for reductions as their “proposed action” for further analysis. They also ruled out two other options that the federal government had initially put forward, which would have involved imposing cuts by following the water-rights priority system or by using an across-the-board percentage.

In its review document, called a revised draft supplemental environmental impact statement, the Bureau of Reclamation also said its analysis found “the risk of reaching critical elevations at Lake Powell and Lake Mead has been reduced substantially” by the wetter conditions in the watershed this year.

The Colorado River provides water for cities, farms and tribal nations across seven states from Wyoming to Southern California, as well northern Mexico.

The river’s flow has declined dramatically since 2000, and research has shown that global warming driven by the burning of fossil fuels has worsened the long stretch of extremely dry years.

Scientists have found that roughly half the decline in the river’s flow this century has been caused by rising temperatures, and that for each additional 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming, the river’s average flow is likely to decrease about 9%.

The water-saving efforts pledged by the states this year are the latest in a series of incremental steps to adapt.

Some California farmers are urging the federal government to consider draining Lake Powell, supporting environmentalists’ push for a ‘one-dam solution.’

In 2019, as reservoirs were dropping, water managers agreed to reduce water use under a deal called the Drought Contingency Plan. But when those reductions were insufficient, the states agreed to additional cuts in 2021, which projections later showed would not be enough to address the risk of Lake Mead declining toward “dead pool” levels — the point at which water would no longer pass downstream through Hoover Dam.

In June 2022, Touton announced at a congressional hearing that the crisis of declining reservoir levels would require much larger reductions of 2 million to 4 million acre-feet per year, and she warned that the government had the authority to “act unilaterally to protect the system.”

But negotiations among state water officials failed to produce an agreement for such large cutbacks.

After federal officials announced their initial plan in April to weigh options that the states opposed, another round of negotiations led to the states’ consensus deal outlining water cutbacks for three years.

Much of the reductions in water use will be secured in exchange for federal funds from the Biden administration. More than $4 billion is available through the Inflation Reduction Act for drought response efforts.

The government also has about $8 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help fund water infrastructure projects over five years.

Under agreements in Arizona, water agencies in the Phoenix and Tucson areas have committed to conservation goals that will leave some water in Lake Mead. The Gila River Indian Community is also receiving $150 million over the next three years to pay for reducing water use.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

Federal officials have said some reductions will come by paying agricultural landowners and irrigation districts to conserve water. The details of those additional agreements are still being worked out.

Parallel to the short-term efforts to shore up reservoir levels, the federal government is starting to weigh options for new long-term river management rules that will take effect starting in 2027.

Scientists have said the region will need to come up with larger reductions in water use to address the river’s chronic water-supply deficit and the effects of climate change.

Last week, the Bureau of Reclamation released an initial report outlining steps toward developing the new rules, which will replace 2007 guidelines for managing shortages.

The agency said it received more than 24,000 comment letters from agencies, organizations, tribes and individuals in the initial stage of this process, with comments focusing on topics such as the river’s supply-demand imbalance, tribal water rights, conservation and sustainable solutions.

The Bureau of Reclamation plans to release a draft environmental review of long-term alternatives by the end of 2024.

Touton said the water-saving efforts that have begun will protect reservoir levels “while we continue to develop long-term, sustainable plans to combat the climate-driven realities” facing the Colorado River Basin.

“Providing the space and stability in the short term allows the basin to now bridge to the long-term conversation,” Touton said.

As for the coming winter, the current strong El Niño has brought forecasts of wetter-than-average conditions in much of the West.

Touton said if there is more snow and rain, that would certainly help. “But we’re not just counting on rain, in the long run, to save us.”

Seven states have agreed to cut water use to boost the Colorado River’s depleted reservoirs, reaching a consensus after months of negotiations.

In many comments submitted to the government, a common thread is a need for greater flexibility in the rules to adapt to extreme droughts and long-term aridification driven by climate change, said Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor of political science at the University of Nevada, Reno.

For one thing, Koebele has suggested analyzing “alternative triggers” for water management. That could mean using a measure such as the average flow over five years or 10 years to determine the severity of a shortage and necessary reductions, instead of using reservoir levels alone to trigger responses.

Koebele and fellow expert Margaret Garcia wrote in a letter to the government that the post-2026 guidelines should not only focus on balancing supply and demand, but also “consider the basin as a holistic and integrated system, rather than a series of storage reservoirs that are managed separately.”

“Having rules that are more flexible than what we’ve got now is going to be really critical to making the basin sustainable in the future,” Koebele said.

She said the above-average snowpack this year and the deal reached by the states “gave some room for the post-2026 process to really kick off and gain some momentum.”

Others say they are concerned that much larger cuts will be needed, and that the region’s water managers seem to be in a pattern of letting the states propose stopgaps that don’t go nearly far enough.

John Weisheit, an environmentalist and co-founder of the group Living Rivers, predicted that federal officials are “going to defer to the states, because they’re afraid of litigation from one state against another.”

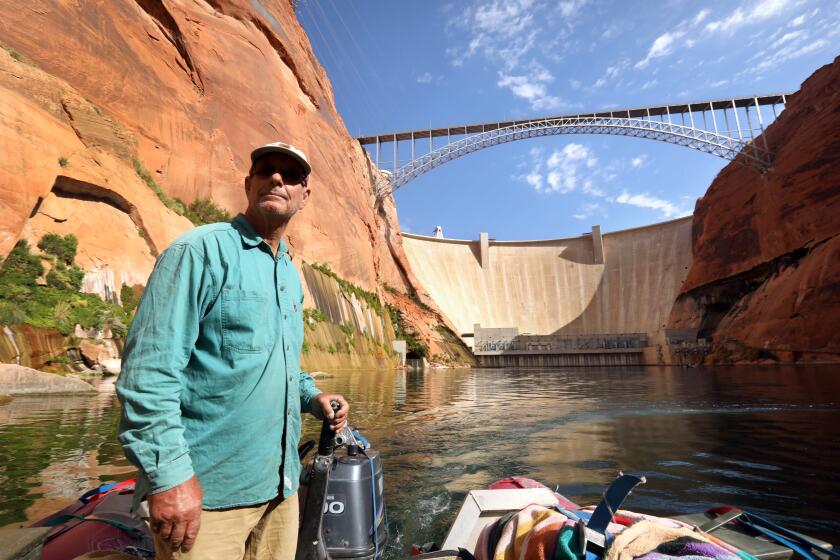

Weisheit has advocated more aggressive steps to plan for dwindling river flows, and has urged the government to consider draining Lake Powell and decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam to restore a free-flowing river upstream from the Grand Canyon — an idea that some influential farmers have recently supported.

Weisheit said he thinks the plans laid out by the region’s water managers to date are far from sufficient to prevent a damaging crash in water supplies.

“They shouldn’t be creating bridges. They need to stop collapse. Because that’s what they’re going to get,” he said.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.