- Share via

The federal government on Tuesday laid out two options for preventing the Colorado River’s depleted reservoirs from falling to critically low levels, saying water cuts could be imposed across the Southwest by following the water-rights priority system or by using an across-the-board percentage.

The stakes in the decision are high for California, which receives the largest share of water from the Colorado River, as well as for Arizona and Nevada. Imposing an equal across-the-board cut would hit California harder, particularly in agricultural regions, while strict adherence to the water-rights priority system would bring larger reductions for cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation presented its alternatives as an initial step in a review aimed at revising the rules for dealing with shortages through 2026. Federal officials said that the proposals still could change and that a solution somewhere between the two options could emerge as representatives of states, water agencies and tribes continue negotiations on how to address the chronic water shortages.

“The prolonged drought afflicting the American West is one of the most significant challenges facing our country today,” Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said. “We’re in the third decade of a historic drought that has caused conditions that the people who built this system would not have imagined.”

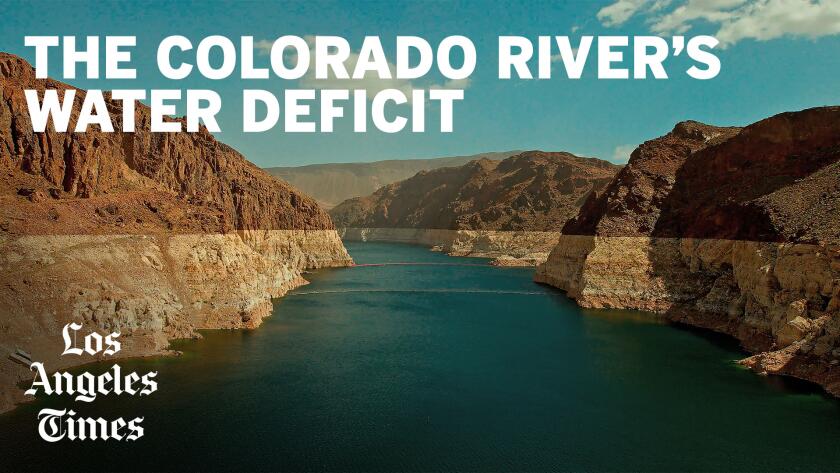

Beaudreau spoke beside other officials in a room overlooking Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, where the reservoir now stands at 28% of full capacity, its surface lapping about 180 feet below the high-water mark along its rocky shores.

The river’s reservoirs have declined dramatically during 23 years of drought intensified by climate change. Even after storms that have blanketed the Rocky Mountains with the largest snowpack since 1997, federal officials say the likelihood of a return to dry conditions means the region still needs a plan for apportioning additional water cuts if necessary over the next three years.

“Everybody understands the significance of the crisis,” Beaudreau said. “I think everybody understands that, as fortunate and thankful we are for the precipitation, that nobody’s off the hook, and that there needs to continue to be unity in trying to develop solutions.”

Los Angeles Times reporter Ian James visits Lake Mead, Hoover Dam and farming areas in Southern California on a tour with managers of the Metropolitan Water District. Leaders of water agencies that supply cities and farms are discussing ways of reducing water use to address the river’s crisis.

Representatives of seven states, water agencies and tribes have been discussing options for reducing water use to prevent the reservoirs from dropping toward dangerously low levels.

The Bureau of Reclamation said it released its initial review of alternatives, called a draft supplemental environmental impact statement, to “address the continued potential for low run-off conditions and unprecedented water shortages” in the Colorado River Basin. Officials said they need plans in place to protect critical levels at Lake Mead and Lake Powell and prevent them from dropping so low that the dams would stop generating power and water deliveries would be at risk.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

The agency is revising the 2007 guidelines for its operations of Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam, which include measures for dealing with shortages through 2026 — but which federal officials say would no longer be sufficient if reservoirs continue to decline.

The Biden administration released its options more than two months after officials from California and six other states presented two conflicting proposals for water reductions.

Closed-door talks among state officials and managers of water agencies are set to continue while the federal government receives input on the proposals. And representatives of California, Arizona and other states pledged to continue working toward a seven-state consensus.

Under one of the options, the federal government would consider making water reductions based predominantly on the existing priority system for water rights.

That would mean smaller cuts or no cuts for agencies and entities that hold older senior rights, including agricultural suppliers such as California’s Imperial Irrigation District, which uses the single largest share of Colorado River water to supply about 500,000 acres of farmland in the Imperial Valley. Strict adherence to the water-rights priority system would also mean large cuts for junior water rights holders that started taking water from the river later, such as the Central Arizona Project, which supplies Phoenix, Tucson and other cities.

Under a second alternative, the Bureau of Reclamation would analyze the effects of reductions “distributed in the same percentage” for all water users in the three Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada.

This approach would mean across-the-board cuts for all water users in the region, including senior water rights holders, amounting to a reduction of about 13% on top of cuts that were already agreed to under a 2019 deal. Agricultural irrigation districts, cities and tribes would all need to participate based on a schedule of reductions tied to the levels of Lake Mead.

Beaudreau said this second alternative reflects the Interior secretary’s authority to “provide for human health and safety” and manage supplies under emergency conditions. If reservoir levels drop further and additional cuts are triggered, this approach would shore up the allocations of agencies with more junior water rights, such as cities in Arizona, Nevada and Southern California.

Both of these alternatives call for progressively larger reductions as the level of Lake Mead declines. The total amount of potential cuts in 2024, including reductions under existing agreements, could reach slightly more than 2 million acre-feet — a major reduction from the three states’ total apportionment of 7.5 million acre-feet.

Last year, federal officials called for cutting water use by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet per year to address unresolved water shortfall and the effects of climate change.

The federal review will also look at a “no action alternative,” analyzing the consequences of staying with the existing rules and agreements if dry conditions return after this year’s wet winter.

“One good year will not save us for more than two decades of drought,” Beaudreau said.

He pointed out that during more than two decades of drought, there have been wet years, such as 2011, followed by a return to dry conditions. The heavy snow this winter, he said, may push “the curve out six months or more.”

“But the trend is still evident over this time period and evident in the modeling,” Beaudreau said. “The downward trajectory of this system has worsened. We cannot kick the can on finding solutions.”

The Bureau of Reclamation will accept public comments on the draft proposals until May 30, and Beaudreau said the agency expects input from states, tribes and water agencies on “fine-tuning or adjusting those alternatives.”

The government plans to adopt a final decision this summer, which will guide dam operations and water releases in the coming year.

“We have a lot of hard work and difficult decisions ahead of us in this basin to achieve our goal, a resilient Colorado River system,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

He and other water managers said they see risks of disputes sparking legal fights, which would hinder further negotiations and continue for years.

“We are committed to avoiding that litigation outcome as best we can by coming up with a collaborative solution,” Buschatzke said.

The long-depleted Colorado River is getting a boost from the largest snowpack since 1997. Rising reservoirs offer some relief amid talks on needed water cuts.

J.B. Hamby, chair of the Colorado River Board of California, agreed and described the outlook in the discussions as “very promising.”

“We’re looking to develop a true seven-state consensus in the coming months, ideally in this next 45-day period if at all possible,” Hamby said.

The options presented by the Bureau of Reclamation show the sorts of cuts that could be imposed if the region doesn’t reach an agreement, said Adel Hagekhalil, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which supplies Colorado River water across the region.

“Neither of the action alternatives presented today is ideal,” Hagekhalil said. He said both “include significant supply cuts that would hurt Metropolitan and our partners,” and that the region should find a better way to manage the river.

“We must keep working to develop a consensus short-term plan, while also collaborating to build long-term solutions that will ensure the river’s lasting sustainability,” Hagekhalil said.

The proposals should provide “bookends” to help in the ongoing talks among the states, tribes and water agencies, Beaudreau said.

“There is actually a lot of unity in the basin in terms of commitment to meeting those conservation goals,” Beaudreau said.

He said the draft proposals are intended to help drive collaboration to “chart out agreements” and develop solutions.

Between the two alternatives, Beaudreau said, there may be a “spectrum” of options.

The Colorado River is approaching a breaking point, its over-tapped reservoirs dropping. Years of drying have taken a toll at the river’s source in the Rockies.

Estevan López, New Mexico’s representative, said the draft proposals provide a “framework on which we can build, and perhaps find something that is partway between those two bookends.”

Some raised concerns about the options. The Imperial Irrigation District said in a press release that it “continues to have concerns with any alternative that involves ‘equal cuts’ among water users” outside the priority system.

In contrast, Democratic Rep. Greg Stanton of Arizona said any proposed action that does not require each state “to equitably share this sacrifice is not viable.”

The option of cuts based on an across-the-board percentage represents the worst case scenario for California, said Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor of political science at University of Nevada, Reno.

By laying out this scenario, Koebele said, the Interior Department is “signaling that they are willing to impose these deep cuts on California, and that California must negotiate with the other six basin states if it wants a better water deal, which is a powerful motivator.”

“I’m hopeful that we’ll see a seven-state consensus emerge in the coming weeks,” Koebele said. With what amounts to a worst-case scenario for California now on the table, she said, any adjustments can be seen as a win for California and help “incentivize continued negotiation and eventual compromise.”

In addition to settling on an approach for the next three years, managers of water agencies still need to negotiate new rules for dealing with shortages after 2026, when the current rules expire.

Whatever option the federal government decides to choose, much will depend on reservoir levels over the next three years.

In the Rocky Mountains, the snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin now measures 156% of the average since 1991, making it one of the largest snowpacks since 1980.

The runoff this spring and summer will boost the level of Lake Powell on the Utah-Arizona border, and the water will make its way to Lake Mead, which stores supplies for Southern California, Arizona, southern Nevada and northern Mexico.

But both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are still expected to remain well below half-full.

“Unprecedented conditions require new solutions,” said Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton. “To meet this moment, we must work together through our shared values and a commitment to protecting the river.”

Since 2000, the river’s flow has decreased by about 20% below the 20th century average. Scientists have found that roughly half the decline in the river’s flow has been due to higher temperatures, which have intensified one of the worst droughts in centuries.

Beaudreau said a key goal is to provide “additional tools in the event that the hydrology continues to deteriorate.”

The Interior Department has also begun providing funds to address drought, pay for conservation efforts and improve water infrastructure, drawing on $8.3 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and $4.6 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act.

Last week, federal officials announced that the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona will receive $150 million over the next three years to pay for reducing water use and leaving water in Lake Mead.

That water, Beaudreau said, will be enough to boost Lake Mead’s level by two feet.

Tribes have vital roles to play in working toward the long-term health and sustainability of the river, said Rosa Long, vice chair of the Cocopah Indian Tribe.

“We must remember that our actions today will have a profound impact on the world our children and grandchildren will inherit. We owe it to them to work together to find solutions,” Long said. “It’s going to take all of us, and it is a very scary situation.”