- Share via

After a winter of record snowpack in California, tens of thousands of acres of farmland were flooded. But, put another way, it was the first time in decades the state saw the revival of Tulare Lake — central to the Tachi Yokut Tribe of the Central Valley.

- Share via

LEMOORE, Calif. — When Leo Sisco was growing up on his tribe’s reservation, he heard elders’ stories about the great lake that once sustained their people, and how it was drained and taken away from them.

This year, Sisco has been witnessing a remarkable transformation as Tulare Lake has reappeared on low-lying farmland near the reservation.

The chairman of the Santa Rosa Rancheria Tachi Yokut Tribe has been noticing the water is attracting many birds, and he has been coming regularly to the lakeshore to offer prayers and look out over the water, which stretches to the horizon.

“I am very happy the lake is back,” Sisco said. “It makes me swell with pride to know that, in this lifetime, I get to experience it. My daughters, my grandson get to experience the lake, and the stories that we heard when we were kids, for us it comes to fruition.”

Pa’ashi, they call it, the life-giving lake that once provided for their ancestors.

The water that has streamed in from the rain and snow this year has for the first time allowed many Tachi people to see the ancestral lake they consider sacred — the center of their creation story, a natural wonder that was obliterated long ago to become lucrative farmland in the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Sisco and other Indigenous leaders say they believe Tulare Lake should be allowed to remain rather than being drained once again to reestablish agriculture, as was done so many times before, including after floods in 1969, 1983 and 1997. They say allowing it to stay would improve life in the valley by providing water storage and allowing the area’s original ecosystem to take root again.

The state will shoulder the $17 million needed to raise the 14.5-mile Corcoran levee an additional four feet, protecting the city from rising floodwaters.

Instead of damming and diverting all the water upstream, they say, restoring flows through the basin would heal the area’s broken relationship to water and bring back a flourishing natural asset in the heart of the valley. They’ve suggested the lake could become the center of a new park.

For now, members of the Tachi Yokut Tribe say the lake’s return offers a chance to experience a part of their identity that they had only heard about in stories and songs passed down from generations ago.

“From a spiritual standpoint, we love seeing the water out there. We love seeing the habitat, seeing the birds,” Sisco said. “We’re very hopeful that it stays.”

::

On a recent afternoon, dozens of people stood at the lake’s edge holding baskets, rattles and freshly sprouted branches of riparian plants.

They lit a bundle of sage, and the smoke drifted over the group.

“As Native people, there has been something missing in our spirit. There’s been something missing in our souls. And what you see behind us now is Pa’ashi has reawakened,” said Robert Jeff, the tribe’s vice chairman. “At the same time, it’s reawakened a lot of spirits.”

Addressing the group, Jeff spoke of the lake’s history: how all the tribes of the area depended on its abundant resources, how they gathered by the lake, and how they once traveled across its waters in boats made of tules.

“This was everything to us,” Jeff said. And now that the lake has reappeared, he said, the tribe feels grateful and wants to help neighboring communities understand the significance and join in supporting its return.

“We’re here to show that it does have meaning, it does have purpose,” Jeff said.

The participants in the ceremony included not only Tachi members but others from nearby tribes.

Standing on the sloping bank of a levee, the group said a prayer.

“This is the people’s lake!” Jeff shouted. “This belongs to all of us.”

Men, women and children laid offerings of plants in the water and sprinkled seeds along the shore.

“Let yourself feel what’s happening. Open up. Because something big’s happening right now,” Jeff told them. “Connect yourself with the water. Touch the water. Touch the mud.”

Some leaned down, put their hands in the water and wetted their necks and hair.

Several men held clapper sticks made of elderberry wood and began tapping a rhythm.

They raised their voices in unison, singing in Tachi to give thanks and welcome the lake’s return.

Ma ko-to na-na ha pana ha-ha ya

Tro-khay-lay ma-ha na-na …

(You, the one, come to me.

Eagle, you and me

Circle, circle around me again. Circle, circle around me again.

Eagle, you and me, come to me.)

: :

During the winter, as heavy rains and snow swept across California, rivers that had dwindled during the drought swelled with runoff and flowed full from the Sierra Nevada into the valley, spilling from channels and gushing through broken levees onto farmland.

As the floodwaters inundated fields that had produced tomatoes and cotton, workers evacuated tractors, pumps and sprinkler pipes.

By mid-March, the lake had reclaimed more than 10,000 acres. It continued growing, inundating dairies, pistachio orchards and farmhouses. It rose beside levees that protect the city of Corcoran and its giant prison complex.

The lake has now grown to cover more than 113,000 acres, an area nearly as large as Lake Tahoe.

As historic storms fill once-dry Tulare Lake and submerge prime California farmland, tensions are building over how to handle the swiftly rising floodwaters.

Members of the Tachi Yokut Tribe said they feel for those who are coping with losses, and don’t want to see people displaced by the water. But they also view the lake’s return alongside their history, including how Native people were decimated and displaced by colonizers, and how they lost the waters and wetlands that had sustained them.

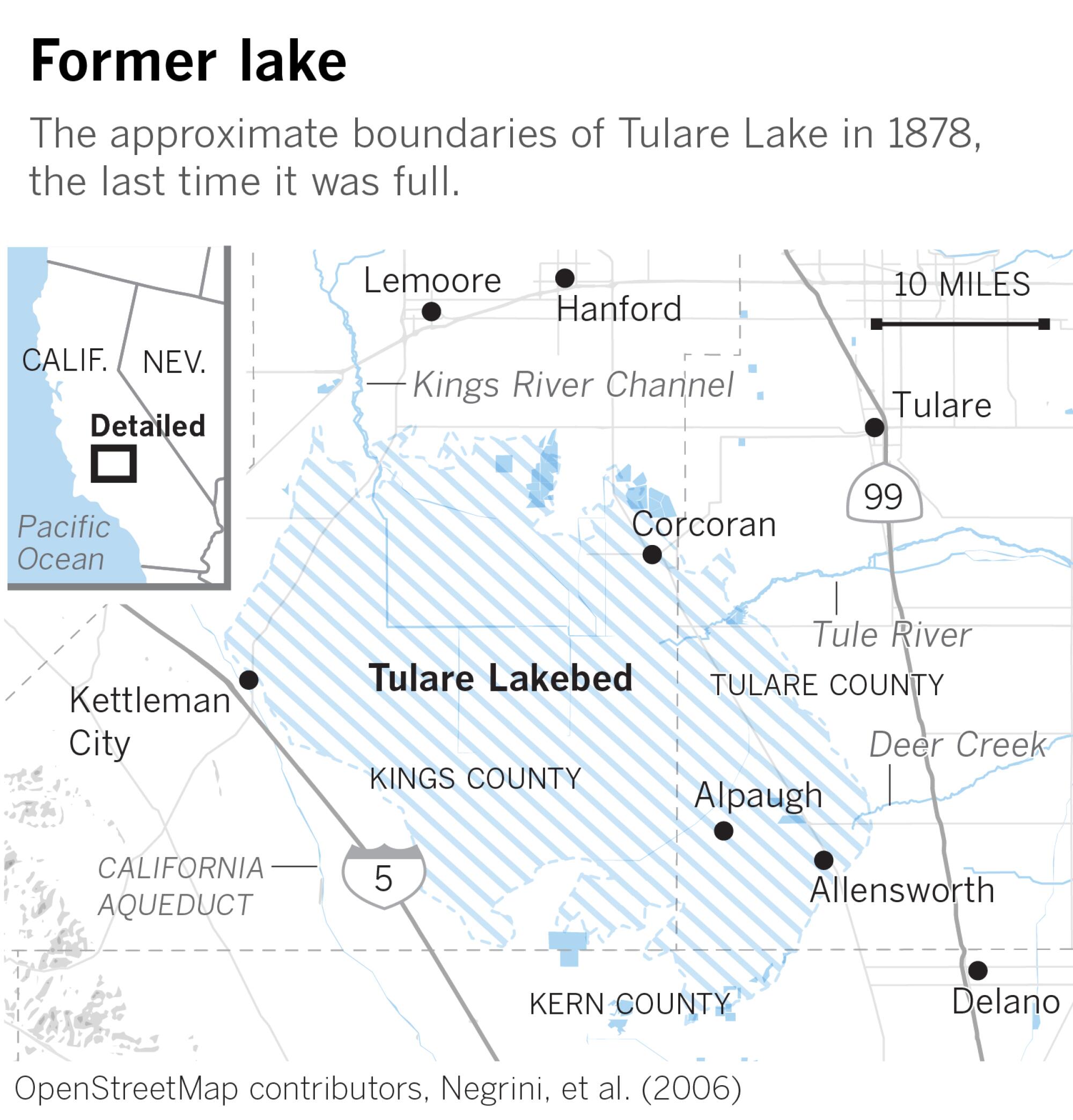

Tulare Lake was once the largest freshwater body west of the Mississippi. Surrounded by vast marshes and thick vegetation, it teemed with birds, beavers, turtles and tule elk.

Tens of thousands of Indigenous people lived and thrived around it. The Yokut tribes made their homes along the lakeshore and the rivers, and moved to higher ground when the lake swelled with runoff.

They built tule rafts and fished with spears and basket traps.

The arrival of Spanish colonizers, followed by fur trappers, gold miners and settlers, devastated the Yokuts. Many died from diseases, and the state government promoted the extermination of Native people with militia campaigns and bounties.

Driven from their lands, the surviving Yokuts ended up living on reservations or marginal lands that had little value to white farmers.

Several families were the first residents of the Santa Rosa Rancheria when the reservation was established in 1934 on 40 acres of farmland.

By that time, the rivers that fed Tulare Lake had been heavily diverted for agriculture. The lake dried up completely during a drought in 1898. And although the lake continued to return in wetter years, it was systematically drained in the early 20th century by a handful of farmers, among them cotton magnate J.G. Boswell.

When dams were built on the Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern rivers, the reduced flows enabled the lakebed to be farmed during all but the wettest years.

The farmers secured water rights under a system of “first in time, first in right,” but the rights of Native people weren’t recognized.

Under a 1908 Supreme Court ruling, tribes are entitled to water rights reserved by the federal government to fulfill the purposes of their reservations. But those rights remain unresolved for the Tachi Tribe and many others.

“Even now, the tribe doesn’t have those first water rights. Instead, they go to the first people who destroyed the natural waterways and moved the water away,” said Shana Powers, the tribe’s historic preservation officer.

She said for the tribe, the draining of the lake and its wetlands was like “destroying the Garden of Eden.”

The lake’s sudden reappearance has started a discussion about how the area could change its relationship to the water, and the tribe wants to help further that dialogue, Sisco said.

“We all have to work together,” Sisco said. “Maybe we can give them a solution.”

::

Sisco drove with several tribal members to a part of the reservation where cottonwoods and willows stand beside a wetland.

The waterway, called Mussel Slough, is a fragment of the natural channels that once fed the lake, a vestige of the ecosystem that was transformed into canals and farmland.

The Tachi are working on a restoration project, planning to plant more trees and put in walking paths. Sisco said restoring the slough can be an example for bringing back more natural waterways.

As he stood by the water, two dark birds floated on the surface — American coots, or mud hens. The tribe calls the birds tatsi and named themselves Tachi after them.

Other birds migrate and fly elsewhere, but the tatsi, like the people, stay.

During the last few years of drought, Sisco said he saw few of these birds. But with the lake’s return, he said, “we see them all the time now.”

Though fears of catastrophic flooding in the Tulare Lake Basin have largely diminished, state officials say we’re “not out of the woods” yet.

Later, Sisco and Jeff stood at the lakeshore near the town of Stratford, looking across miles of inundated farmland.

“I think it will bring life back to this entire valley,” Sisco said.

“I am very happy the lake is back. It makes me swell with pride to know that, in this lifetime, I get to experience it. My daughters, my grandson get to experience the lake, and the stories that we heard when we were kids, for us it comes to fruition.”

— Leo Sisco, chairman of the Santa Rosa Rancheria Tachi Yokut Tribe

He acknowledged that agricultural landowners have long viewed the lake bottom as valuable land to grow cotton, tomatoes and other crops. But he and other tribal members say they believe the growers could farm elsewhere, and perhaps receive financial assistance to make that possible — which would most likely require involvement by local, state and federal agencies.

Allowing space for the lake wouldn’t mean ending farming in the area, Sisco said. “I think there is enough room for the entire lake and some farming around it.”

The Tachi Tribe, which has nearly 1,200 members, also owns farmland on higher ground.

Letting nature take its course, Sisco said, would benefit not only the ecosystem and the Tachi Tribe, but also other sister tribes and other communities.

Jeff said the lake could be used as a reservoir, storing water on the valley floor instead of up in the mountains, and bringing back its wetlands.

“Think about it in terms of Pa’ashi National Park, Tulare Lake National Park,” Jeff said. “This water needs to be protected.”

Even if the lake doesn’t gain protection as a park, Jeff said, restoring it would help address the valley’s water problems. He pointed out that chronic overpumping of groundwater to supply farms has led to falling aquifer levels, affecting the quality of drinking water and causing the ground to sink several feet in recent years around Corcoran and other nearby areas.

Although impermeable clay prevents water from infiltrating in many areas of the lakebed, members of the tribe said there are certain areas where recharge can occur, and that keeping the lake would restore an ecological balance.

“All we want is balance,” Jeff said. “This land needs that lake.”

The last time the lake grew to nearly this size in 1983, the water stayed for about two years.

Environmental advocates have agreed with the tribe, saying making room for the lake would bring many benefits, among them preparing for more intense floods with climate change.

Some in the agriculture business have also supported the idea, suggesting Gov. Gavin Newsom could use eminent domain to set aside some land for the lake.

For now, state officials have sought to limit the lake’s rise by opening a rarely used relief valve, diverting floodwaters from the Kern River into the California Aqueduct. But state regulators have also told local agencies that their plans for combating groundwater overpumping are inadequate. And to achieve long-term sustainability requirements, many parts of the San Joaquin Valley are expected to have to take some farmland out of production, transitioning these lands to solar farms, habitat restoration or other uses.

For the first time since 2006, California has opened a flood relief valve on the Kern River to ease pressure from the heavy Sierra snowmelt. The valve will divert floodwaters into the California Aqueduct for use in Southern California.

“There’s a lot of change happening in the valley that is driven by groundwater management, that is driven by flood protection,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the state Department of Water Resources. “I would think that the local entities would want to consider that in the context of everything else they’re considering relative to land transition.”

Scientists have also been analyzing what the lake’s return could mean. Peter Moyle, a leading fish scientist and UC Davis emeritus professor, wrote in a blog post that restoring even a portion of the lake would be an astonishing accomplishment.

“Perhaps the time has come to let Lake Tulare and its surrounding marsh lands return to their more natural state,” Moyle wrote.

“Now, as the lake arises again, the same question persists: why is it legal to drain Tulare Lake for private gain? And shouldn’t the descendants of the Yokuts bands who had their lake and lands stolen from them have something to say about what happens to their ancestral home? Is Nature telling us that a new Lake Tulare paradigm is needed, featuring the return of the lake to a more natural ecosystem?”

::

When dozens of people gathered by the lake for the ceremony, they were welcomed by Kenny Barrios, a Tachi Tribe cultural liaison who teaches the language, songs and traditions to young tribal members.

“I see a good future for us now that we have the lake here,” Barrios said. “It’s going to continue to bring life, as long as we all can fight for it, for this thing to be here. This Pa’ashi is not just important to Native people. It’s important to everybody in the Central Valley — not just my kids, not just your kids, everybody’s kids!”

Barrios said the tribe is looking seven generations into the future.

“It’s going to bring life. It’s already doing it,” Barrios said as a breeze sent ripples across the lake’s surface.

Standing on the shore, some people took off their shoes and waded in.

Chrissy Atwell, who is of Tachi and Chukchansi ancestry, came from Big Sandy Rancheria of Western Mono Indians. She dipped a basket in the lake and dribbled water on the neck of an elder, who bowed down at the shore. Then Atwell doused her own neck and shoulders.

“There is not a better thing to do with these baskets than to give them a little cleansing in the lake,” Atwell said afterward.

By taking part, she said, she was “spiritually connecting with and supporting our tribes.”

Carmen Moreno, who is Tachi and Wukchumni, stood in the water and launched a small boat made of tule reeds. She gave the boat a push, then splashed water to send it off.

As the boat drifted away, she bent down and washed her face.

Moreno came with her 13-year-old son. She said she wished her mother, a fluent Tachi speaker who died several years ago, could have seen the lake. She said her mother told her stories about the lake, including how it provided everything the people needed, and how the lake was a gathering place for tribes.

“It’s like a blessing. It’s like us visiting our family,” Moreno said.

Two young tribal members carried bunches of tules and waded into the water. Leaning down, they loosened the mud with their hands and gently planted them.

“I grabbed the tule from where my grandma lives,” said Diamond Garcia, a 21-year-old Tachi Yokut Tribe member. “I just went down and pulled some up carefully so I wouldn’t rip the roots.”

Garcia said she hopes the lake stays. And when she comes back, she hopes to see the tules growing, spreading and reclaiming the shore.