- Share via

CORCORAN, Calif. — Sixth Avenue used to cut through miles of farmland. Now, the road has disappeared under muddy water, its path marked by sodden telephone poles that protrude from the swelling lake. Water laps just below the windows of a lone farmhouse that sits alongside the submerged route.

Thousands of acres of cropland have been inundated in this heavily farmed swath of the San Joaquin Valley. And the water just keeps rising.

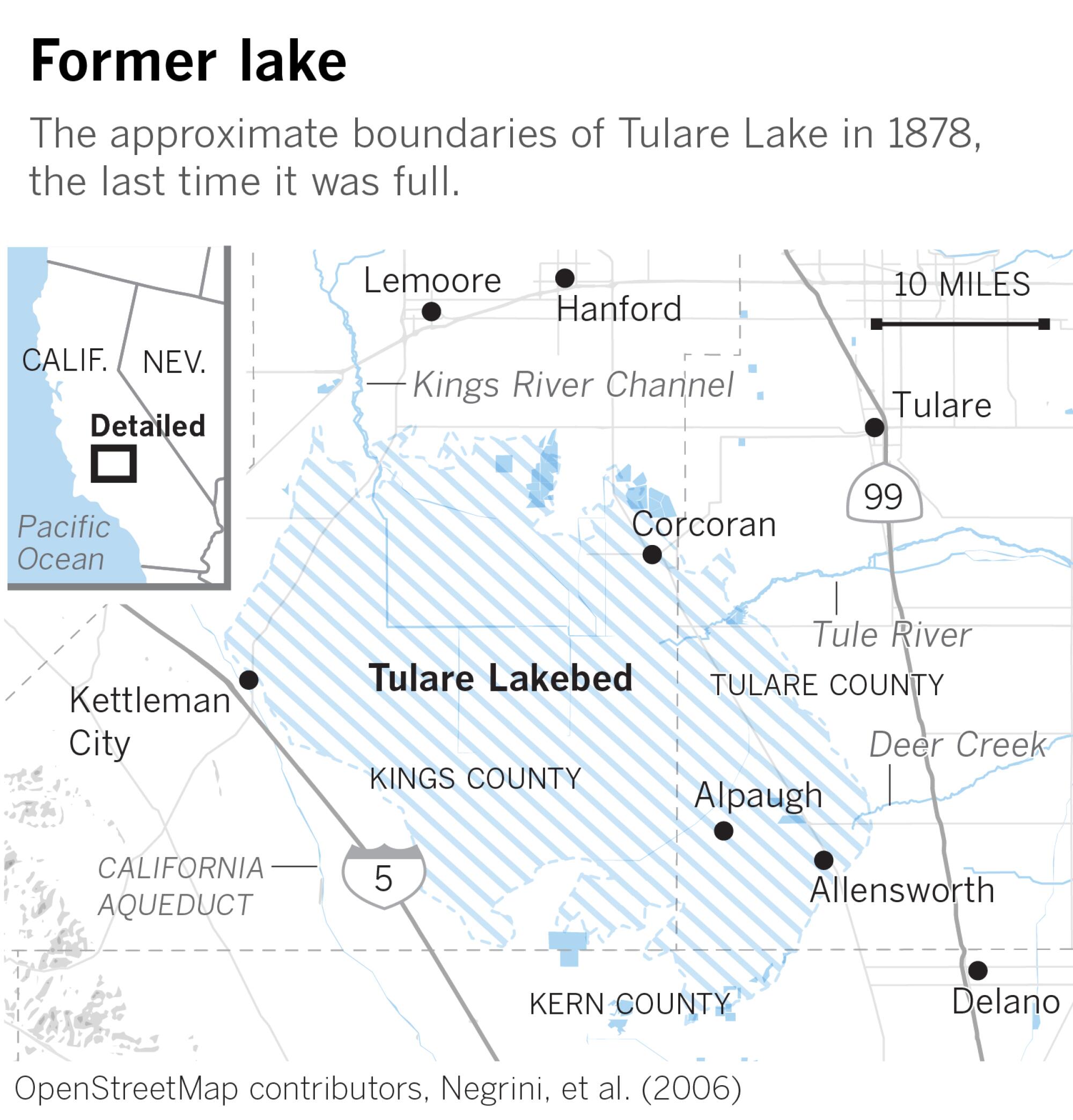

For the first time in decades, Tulare Lake is reappearing in the valley, reclaiming the lowlands at its historic heart. Once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, Tulare Lake was largely drained in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the rivers that fed it were dammed and diverted for agriculture.

This month, after a historic series of powerful storms, the phantom lake has reemerged. Rivers that dwindled during the drought are swollen with runoff from heavy rains and snow, and are flowing full from the Sierra Nevada into the valley, spilling from canals and broken levees into fields that usually teem with lucrative plantings of tomatoes, cotton and hay.

“This is unreal,” said Mark Grewal, an agronomist who has worked on the area’s farms since 1979, surveying floodwaters that stretched to the horizon. “I’m just amazed at how fast it filled.”

Along with awe, Tulare Lake’s sudden reemergence has fueled conflict in one of California’s richest agricultural centers, as the spreading waters swallow fields and orchards and encroach on low-lying towns. In a region where the major agricultural landowners have a history of water disputes, the floods streaming into Tulare Lake Basin have reignited some long-standing tensions and brought accusations of foul play and mismanagement.

Residents in rural towns such as Alpaugh and Allensworth fear their homes won’t be prioritized for protection from the rising waters. And as the water has overwhelmed canals, tensions have flared over where the floods should be directed, and which farmland should go under first.

“When there’s this much water, nobody wants it,” Grewal said. “The growers want to keep it off their land.”

More water is set to come rushing into the basin in the coming weeks from the rivers that feed it — the Kings, St. John’s and Tule, among them — sending flows coursing through the network of canals that crisscross the lake bottom.

“All of the arteries are full, and they’re going to get fuller,” Grewal said. “It could be as big or bigger than ’83.”

That was the lake’s last high point, when heavy rain and snow unleashed runoff that, according to Grewal’s records, covered about 82,000 acres. During that refilling, and a smaller reappearance in 1997-98, Grewal managed farmland for J.G. Boswell Co., the area’s largest landowner. He now runs his own consulting business, working with growers in the U.S. and internationally.

The resurgent lake has already flooded more than 10,000 acres of farmland, Grewal said, and will continue expanding over the next two months as historic snowpack in the Sierra Nevada melts and flows to the valley.

Near the town of Stratford, Grewal drove along an elevated roadway through fields that usually produce tomatoes and where water now pooled in the dark rows of lakebed soil.

“This is all going to go underwater,” he said.

In previous flood years, Grewal said, levees were typically cut open in an agreed-upon order, sending water from one enclosed “cell” to another, and filling the lake bottom in an orchestrated way. This time, he said, there have been delayed responses and more levee breaches than in the past.

“The flood isn’t being handled properly,” said Grewal, noting he works with one grower who has 2,400 acres of pistachio trees choking underwater. “It’s a mess, because there are breaks everywhere.”

In one mysterious incident, Jack Mitchell of the area’s Deer Creek Flood Control District alleged that someone had intentionally cut open a levee with a backhoe in the dark of night. He says he knows who did it, but the report hasn’t prompted an investigation.

Elsewhere, Mitchell said, the Boswell company at one point used a massive piece of equipment as a barrier, keeping Mitchell’s crew from cutting into a levee to send water flowing toward the basin bottom and away from towns. “It’s silly the way they’re doing it,” he said at the time. “It wants to go to the lake, and they won’t let it go.”

The Kings County Board of Supervisors stepped in to settle the dispute, ordering Boswell’s managers to cut a levee and send water toward the lake bottom — and into their fields and those of other growers — rather than trying to pump the water up to higher elevation areas.

“They weren’t really happy with me,” said Supervisor Doug Verboon. “To have someone come and tell them what they have to do is not good for them. But what it did was, it opened a line of communication. So now we’re speaking to each other and sharing ideas.”

Boswell representatives did not respond to emails from The Times requesting an interview.

Over the years, the company has built levees on the old lakebed bottom to control floodwaters. “The idea is that you want to flood the least amount of acres the highest you can to minimize losses,” Grewal said.

Local responsibility for flood control in the basin is split among about a dozen reclamation districts, which are controlled by landowners. State officials have visited the area to discuss response efforts. Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth told the news website SJV Water that she and her team are assessing the state’s authority to intervene, if needed, to help “deal with the challenges we’ve already seen emerging in the last 10 days.”

Verboon said one issue that has complicated matters is bad blood between the Boswell company and John Vidovich, who also owns vast acreage in the basin. Their disputes, some rooted in disagreements over water rights, have led to litigation, and Verboon said they have refused to talk to each other.

“We all pay the price when they’re fighting,” Verboon said. But he said he anticipates the flooding, which is set to worsen in the coming weeks, could spur the two camps to “work together to move this water out of here.”

During the 1983 floods, Grewal said, a decision was made to take a large portion of the water that was rushing in and divert it to Southern California cities. “They pumped a million acre-feet to L.A. that would have gone to the lake,” he said. “Boswell paid for that, just to dewater the lake faster.”

Farms in the lake’s footprint rely on a mix of water from irrigation canals and groundwater. In many years, limited surface supplies have led growers to heavily pump from wells. As the aquifer has dropped, the land has been sinking. In parts of the watershed, that has altered where water flows.

In an interview, Vidovich did not address the flood response. He said some of his company’s almond and walnut orchards have flooded, and that “you just have to hope that the trees get enough oxygen that they survive.”

Other farmers have echoed the concern, saying if water remains on orchards as temperatures rise, the roots will rot and kill the trees.

People in the rural California community of Allensworth have been fighting floodwaters by building berms, and are bracing for the next storm.

In low-lying Allensworth, residents have used shovels and tractors to build berms, trying to prevent ditches from overflowing and sending water toward their homes. Its leaders have appealed for more help from county and state officials, as well as the adjacent railroad. Despite an evacuation order, many residents have said they plan to stay to try to defend their homes.

“The real spirit of Allensworth, to me, is to help the people that are in need in our community,” said Melvin Santiel, the pastor of Allensworth Christian Church. “And we have to do it because we don’t have anybody that’s going to come and help us.”

Santiel said he’s concerned that some growers have been trying to keep water off their lands, and that canals and levees have suffered from a lack of maintenance. “California infrastructure was not ready for this,” Santiel said. “We have to come up with a major plan, because this water’s not going to stop.”

Grewal said he thinks Allensworth will be in danger when the snow melts, and “they need to leave.”

Tulare Lake’s return, he said, could put valuable land out of commission for as long as two years, reducing production of tomatoes, pima cotton, safflower and alfalfa. He said he expects farmworkers will need to relocate, and prices of processed tomatoes and other products will rise.

Nevertheless, the region’s large growers have weathered past floods and will survive this one, Grewal said. And the bounty of water will bring a meaningful boost to supplies.

A new state plan for the Central Valley calls for spending as much as $30 billion over 30 years to prepare for the dangers.

In satellite images of the San Joaquin Valley, the footprint of the old lakebed stands out as a darker, grayish area in the patches of farmland. In the days before the damming of rivers, the lake could stretch for 790 square miles, four times the size of Lake Tahoe, with depths of 30 feet.

Before white settlers arrived in the Central Valley in the 1800s, Tulare Lake was the center of life for the Native Yokut people who lived by its shores and along the rivers. Then farmers began diverting water and claiming land in the lake bottom.

More than a century later, members of the Santa Rosa Rancheria of the Tachi Yokut Tribe live near what was once the lake’s north shore. The tribe’s leaders have agreed to diversions that will channel some of the floodwaters onto their lands, easing pressure on the system while also helping to recharge groundwater.

The lake’s rise is “just a very small reminder of what was once here,” said Leo Sisco, the tribe’s chairman.

The phantom lake, which the tribe calls Pa’ashi, remains central to their spiritual beliefs. Their traditional songs include passages that say when the water rises, “that’s the lake telling us, ‘OK, it’s time for you guys to get out of here now,’ ” said Robert Jeff, the tribe’s vice chairman.

“So that’s when our people would pack up,” Jeff said, “and we’d head to the mountains, to our other villages, until the water receded.”

“It’s time to move to higher ground,” he said.

Times staff writer Jessica Garrison contributed to this report.