Drought-ravaged Colorado River gets relief from snow. But long-term water crisis remains

- Share via

Four months ago, the outlook for the Colorado River was so dire that federal projections showed imminent risks of reservoirs dropping to dangerously low levels.

But after this winter’s major storms, the river’s depleted reservoirs are set to rise substantially with runoff from the largest snowpack in the watershed since 1997.

The heavy snow blanketing the Rocky Mountains offers some limited relief as water managers representing seven states and the federal government continue to weigh options for cutting water use.

Despite the reprieve, officials are still grappling with how to address the river’s chronic water deficit, which has deepened during 23 years of drought intensified by climate change.

Los Angeles Times reporter Ian James visits Lake Mead, Hoover Dam and farming areas in Southern California on a tour with managers of the Metropolitan Water District. Leaders of water agencies that supply cities and farms are discussing ways of reducing water use to address the river’s crisis.

“It’s a great snowpack,” said Bill Hasencamp, manager of Colorado River resources for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “It gives us breathing room. It gives us a little bit of space to negotiate.”

The complicated politics surrounding the river grew especially contentious in January, when officials from California and six other states presented two conflicting proposals for water reductions.

The tensions now appear to have eased somewhat with the snowy winter. Managers of water agencies throughout the region have pledged to continue negotiating in an effort to reach a seven-state consensus, and the wetter conditions will likely give them greater leeway in the talks.

The plentiful snow could also alleviate some of the pressure for making large cuts right away as the Biden administration considers alternatives for managing reservoir levels over the next three years.

“This snowpack means we don’t need nearly the level of cuts as we thought we might have just four months ago,” Hasencamp said during a tour of water infrastructure and farming areas along the river.

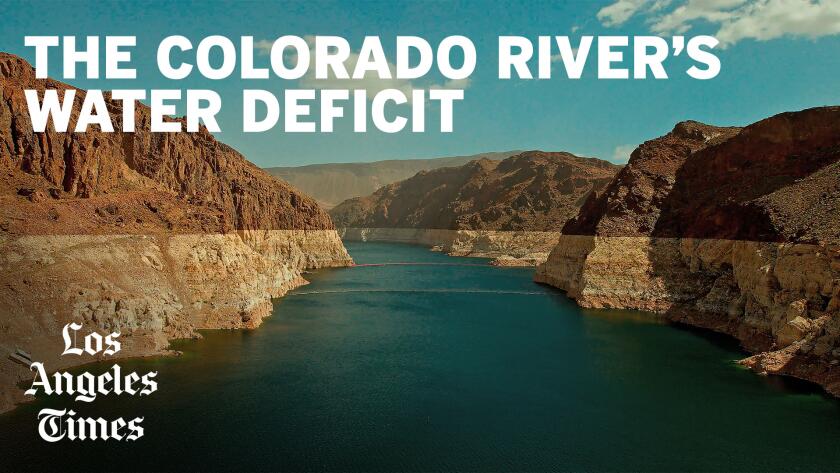

The tour began at Hoover Dam near Las Vegas, where Lake Mead has recently declined to its lowest levels since it was filled.

The reservoir, which in 2000 had been nearly full, now stands at just 28% of full capacity. On its rocky shores, a whitish coating of minerals marks the high-water line about 180 feet above the water’s surface.

Upstream in the Rocky Mountains, the snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin measures 150% of the average since 1986, making it one of the largest snowpacks since 1980.

The runoff this spring and summer will boost the level of Lake Powell on the Utah-Arizona border, and the water will make its way to Lake Mead, which stores supplies for Southern California, Arizona, southern Nevada and northern Mexico.

Hasencamp said the runoff should eventually raise Lake Mead’s level by 20 to 30 feet, which might return it toward an “equilibrium level,” though both major reservoirs are still expected to remain well below half-full.

“This bump provides us a little bit of time, knowing that, at least for the next two to three years, we’re not going to have to make huge cuts,” Hasencamp said. The unusually wet winter, he said, “will give us a little bit of time to develop a longer-term solution.”

The historic snow and rain in California this winter has also allowed the district to “back off on the Colorado River supplies,” which will in turn help boost water levels at Lake Mead, Hasencamp said.

He said various existing plans to voluntarily reduce the use of Colorado River water should be sufficient for the time being, but that it’s still crucial to develop plans for adapting as climate change continues to shrink the river’s average flow.

“The current use of Colorado River water is not sustainable,” he said. “We have to come to grips with the fact that we have to permanently reduce our use by about 25% or more of Colorado River water. So we’re going to need more innovative ways to stretch our water supply.”

Since June, federal officials have been urging representatives of the seven states to agree on plans for major water cutbacks. The federal Interior Department and Bureau of Reclamation have been studying options for preventing reservoirs from reaching critically low levels, and soon plan to release a preliminary draft review of alternatives.

Managers of water agencies say they also will hold more talks to try to reach a consensus. In addition to settling on an approach for the next three years, they still need to negotiate new rules for dealing with shortages after 2026, when the current rules expire.

California has the largest water entitlement of any state on the Colorado River, supplying farmlands in the Imperial and Coachella valleys and cities from Palm Springs to San Diego.

Two months ago, federal officials told states that depend on the Colorado River to make plans for major cuts. Negotiations have yet to produce a deal.

At Lake Mead, the water courses through Hoover Dam’s intakes and rushes through 30-foot-wide pipes called penstocks. The water spins turbines, generating enough electricity for about 350,000 homes, and continues downriver to Lake Mohave.

At Lake Havasu, on the California-Arizona border, the Metropolitan Water District operates the W.P. Whitsett Pumping Plant, which since 1941 has been taking in water and pumping it uphill to start its journey across the desert in the 242-mile Colorado River Aqueduct.

“We keep Southern California hydrated,” said Derek Lee, the MWD team manager at the pumping plant, explaining that five pumping plants lift the water more than 1,600 feet along the aqueduct.

He showed a group of reporters the plant’s nine 6-foot-wide pipes, which slant up a rocky hillside and converge in larger 10-foot pipes.

During the past three years, as the district’s other imported supplies from Northern California were cut during the drought, the intake plant operated near full capacity, typically running seven or eight pumps, Hasencamp said.

But this year, the district has sharply reduced pumping from the Colorado River, lately running just three or four pumps.

The tour continued by plane, flying over farmlands around Blythe where the MWD has a program that pays growers who agree to leave some of their fields dry. While the district’s managers touted their efforts to reduce reliance on the Colorado River, federal officials held events elsewhere along the river this week to announce new funding for conservation programs and water infrastructure.

Visiting Imperial Dam, Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau and others from the Biden administration announced about $585 million for repairing and improving water systems across the West, part of $8.3 billion for water infrastructure projects included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Beaudreau said the infrastructure money, along with $4.6 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act that will be used to address drought, “represent some of the largest investments in drought resilience in America’s history.”

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

In Arizona, federal officials announced that the Gila River Indian Community will receive $150 million over the next three years to pay for reducing water use and leaving a portion of their water in Lake Mead. The tribal government will also receive $83 million to expand water reuse with a reclaimed water pipeline project.

Beaudreau said these efforts will significantly benefit the region, and the Interior Department will announce more funding in the coming months to conserve water and “provide for long-term sustainability.”

Because the largest share of the river’s water is used for agriculture, a portion of the federal money is expected to go toward paying growers who temporarily forgo some of their water and leave fields dry.

While this year’s rain and snow will help, “we are definitely not out of the woods,” Beaudreau said. “It took us 23 years to get into this deficit, and it’s going to take a lot more than one year of snowfall to get us out.”

Continuing their Colorado River tour, the MWD officials visited with farmers in the Bard Water District who are participating in a seasonal land-fallowing program. During the summer, the growers agree not to plant crops like wheat or cotton on some fields, and receive compensation while continuing to grow more lucrative vegetable crops in other seasons.

They also met with leaders of the Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, who have a voluntary program in which the MWD pays farmers not to grow crops on some of their lands from April through July, supporting an effort to boost the levels of Lake Mead.

The Quechan Tribe is one of 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin, and Native leaders have been calling for their inclusion in talks on river management where they previously were largely excluded.

Last month, Quechan Tribe President Jordan Joaquin was appointed as a member of California’s Colorado River Board by Gov. Gavin Newsom, becoming the first tribal representative to serve in the role. Joaquin called it an important step toward more tribal representation in decision-making.

“How do we solve our water problems? Well, you solve it by having everybody at the table, and that includes tribes,” Joaquin said. “Tribal leaders need to be there.”

As climate change and overuse threaten the Colorado River, Native American tribes seek a larger role in the river’s stewardship.

He and other representatives of the tribe said they are optimistic about finding solutions, and that the river is central to their way of life.

“We definitely have to have a living river,” said Frank Venegas, a water technician for the tribe. He stood beside a wetland park where a restoration project has brought back flourishing vegetation and birds.

“This is life for the Quechan people,” Venegas said.

As for the unresolved water shortage, he said, “we all have to sit together and we’ve got to develop an answer together.”

Hasencamp shared similar optimism as the tour ended at the F.E. Weymouth Water Treatment Plant in La Verne.

“Three years from this summer, we need to have this next set of generational agreements approved and in place, so we have three years to figure out the future of the Colorado River, how to make the river sustainable,” Hasencamp said. “It’s going to be hard work. We’re going to have to give and take. But I think people recognize that’s by far the best approach, as opposed to approaches that more likely lead to litigation.”

The MWD delivers water that its member agencies supply to 19 million people across Southern California. On average, about one-fourth of the region’s water supply comes from the Colorado River.

Adel Hagekhalil, the district’s general manager, said it’s important that the region work together to invest in solutions, such as recycling more wastewater, capturing more stormwater and cleaning up contaminated groundwater. He pointed out that Arizona and Nevada water agencies are helping fund initial work on a large water recycling project in Southern California.

He suggested the Colorado River Basin should one day consider creating a single water authority to govern water management across the seven states, something like the Tennessee Valley Authority. He said such a body could help guide the region in making “watershed investments that save the entire river as a whole.”

“We have to think holistically as one,” Hagekhalil said. “We’re stronger together, more effective together than if we’re fighting.”

He said the plentiful rain and snow shouldn’t diminish the urgency of finding long-term solutions for the Colorado River.

“Nature gave us a lifeline. Let’s not waste it,” Hagekhalil said. “Let’s figure out how we can now prepare.”

“This is the new climate,” he said. “And we need to adapt to it.”