Column: Hydrogen is a crucial climate solution. It’s also a distraction

- Share via

During a key scene in the Marvel film, “Avengers: Infinity War,” Benedict Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange character looks into the future for a preview of the challenges facing him and his superhero friends as they struggle to save humanity. He comes out of a trance and tells his friends that he sees 14 million possible outcomes — just one of which involves them defeating evil.

Later, during the climactic battle in “Avengers: Endgame,” he’s asked whether the heroes are on the verge of that winning outcome.

“If I tell you what happens, it won’t happen,” he replies.

Fortunately, here in the real world we’ve got better odds of stemming the climate crisis than 1 in 14 million.

From renewable energy to public transit to eating less meat, there are many solutions — and many ways they might fit together to help us stop burning the coal, oil and natural gas making our lives increasingly hellish. There’s more than one right answer to which we can collectively devote our time, energy and money — without worrying whether we’re following the one true path.

You're reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Which makes the blistering debate over the merits of hydrogen as a climate solution all the more frustrating.

If you’re not plugged into the hydrogen discourse, the clean-burning fuel is at the center of the climate conversation this week following a major announcement from the Biden administration. Federal officials have selected California and 15 other states to receive $7 billion in hydrogen funds from 2021’s infrastructure law, as my colleague Hayley Smith reported.

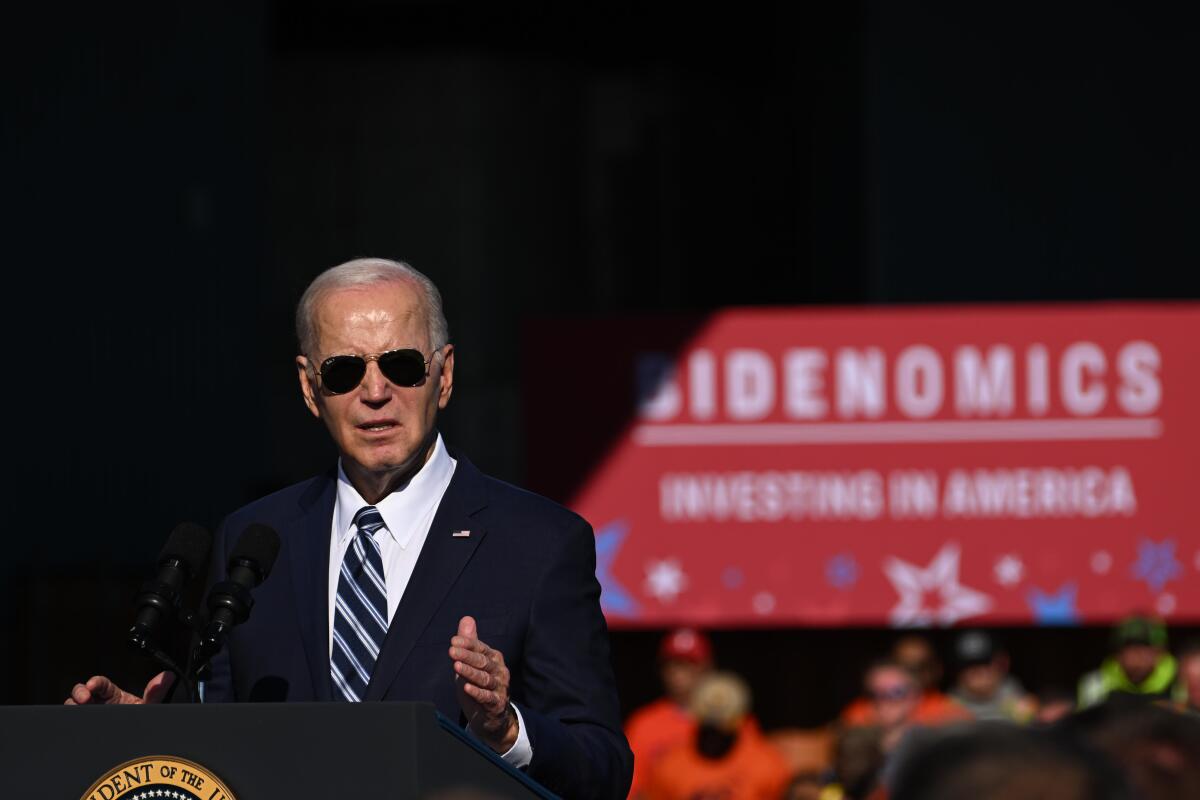

President Biden called the money “one of the largest advanced manufacturing investments in the history of this nation,” saying it would attract $40 billion in private investment and create “tens of thousands of good-paying jobs,” mostly union jobs.

“It’s a $50-billion investment in our economic competitiveness,” Biden said at a Philadelphia news conference.

There’s widespread agreement that hydrogen can help clean up industries where switching from dirty fuels to electric power is way too expensive — industries such as shipping, aviation, cement manufacturing, steelmaking and possibly long-haul trucking. Swapping in a fuel that emits no planet-warming carbon dioxide when burned is a straightforward climate solution.

Beyond those “hard to electrify” sectors, though, widespread agreement is hard to come by.

Many electric utilities see hydrogen as a valuable substitute fuel at gas-fired power plants, to help keep our lights on — and air conditioners blasting — after sundown, when solar panels stop generating. Some port officials, including those in L.A. and Long Beach, consider hydrogen a clean fuel that could power cargo-handling equipment and, potentially, shorter-haul trucks.

Those goals sound reasonable on the surface. But they’ve infuriated environmental justice activists, who see hydrogen as a continued threat to the air breathed by low-income people of color — and also, in some instances, a climate danger.

Hydrogen emits no carbon dioxide or other climate pollution when burned. But pipeline leaks are a potential menace — in part because hydrogen is a powerful heat-trapping gas in its unburned form, and in part because the fuel is highly flammable.

Hydrogen combustion also generates lung-damaging nitrogen oxide — already a burden in many polluted communities.

“If we’re going to spend money on something, this isn’t it. Or at least, this can’t be the only thing,” said Ari Eisenstadt, energy equity manager for the California Environmental Justice Alliance, a coalition of advocacy groups.

Hydrogen definitely isn’t the only thing we’re spending money on.

The Inflation Reduction Act signed by President Biden last year included $370 billion for climate and clean energy initiatives. Los Angeles has invested heavily in solar, wind and battery storage on its quest for 100% clean electricity by 2035. Port officials in L.A. and Long Beach have begun to embrace battery-electric trucks, part of a pledge to clean the air in nearby neighborhoods.

As far as hydrogen supporters are concerned, the fuel is simply another tool in the toolbox.

“If you put the battery revolution together with a clean hydrogen revolution, we begin to cover most of the bases that the fossil-fuel industry has covered,” said Denny Zane, policy director of transit advocacy group Move LA.

But even some climate activists who see a role for hydrogen say the federal funding announced Friday is badly flawed.

In part, that’s because of how the funds are being rolled out.

Critics say state and federal officials have offered remarkably little insight into how California might spend the money, which will start with $20 million and could ultimately amount to $1.2 billion as hydrogen projects proceed. Sasan Saadat, a policy analyst at nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, told me Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration has refused to share with the public which projects are being considered for funding, asking anyone who wants to learn details to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

Earthjustice and its allies have refused to sign.

“Virtually at every turn, we’ve been stymied from getting basic information,” Saadat said.

In a letter to the Biden administration last week, the California Environmental Justice Alliance and other groups urged federal officials to withhold additional hydrogen funding from the Golden State until it stops demanding non-disclosure agreements — and until state agencies do far more to solicit input from communities breathing polluted air.

Those communities include several Latino neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley, where the gas-fired Valley Generating Station pollutes the air. It’s one of a few power plants that the L.A. Department of Water and Power hopes to convert to hydrogen.

DWP leaders have framed those conversions as the best way to ditch fossil fuels without causing blackouts. It’s a similar story at the L.A. and Long Beach ports, where officials say hydrogen would clean the air while keeping operations running smoothly.

Environmental justice activists aren’t convinced.

On the one hand, they’re glad California has pledged to use federal funding to produce hydrogen via climate-friendly methods, such as splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen atoms with renewable electricity — a process known as electrolysis. That’s a sharp contrast with some of the other states getting federal dollars, which will use fossil fuels to make hydrogen.

Even in California, though, critics say the money could be a boon for oil and gas companies.

At Newsom’s direction, the state funneled its many hydrogen proposals into a single federal funding application submitted by a public-private partnership called the Alliance for Renewable Clean Hydrogen Energy Systems, or ARCHES. The coalition includes more than 400 groups and other entities — among them fossil-fuel companies Chevron and Southern California Gas Co.

Chevron is one of several oil and gas stalwarts making a play for hydrogen, having recently acquired a majority stake in a Utah hydrogen storage project that could help L.A. stop burning coal at a power plant the city operates in the Beehive State.

Many fossil-fuel companies see hydrogen as a way to maintain the value of their infrastructure and expertise, rather than fading into irrelevance. That includes SoCalGas, whose executives hope to spend billions of dollars building pipelines to bring hydrogen to power plants and factories in the L.A. Basin, as well as the ports — a potentially lucrative project known as Angeles Link.

“Working with ARCHES and state policymakers in support of California’s clean energy and climate goals is a central focus of SoCalGas,” the company’s president, Maryam Brown, said in a written statement after the funding announcement.

Fossil-fuel industry investments could have significant climate benefits. But again, many activists are skeptical.

As a power-plant solution, they see hydrogen as wildly inefficient, requiring the use of lots of electricity to create a fuel that will simply be burned again for electricity. They’d prefer that solar and wind farms dedicate their output elsewhere. They also worry hydrogen will be used as an excuse to slow the transition to electric trucks, which they see as a more sure-fire solution.

With limited money and limited time to avoid the worst consequences of the climate crisis, those activists say we ought to be laser-focused on electrifying as much of the economy as possible, including cars, trucks, home heating and cooking.

Only then, in their view, should we turn to hydrogen and other clean-burning fuels preferred by the fossil-fuel industry.

“It feels like a lot is going to be sacrificed at the altar of hydrogen industry promotion,” Saadat said.

State officials are sympathetic to those fears but insist they miss the full picture.

After hearing from environmental justice activists, I spoke with ARCHES Chief Executive Angelina Galiteva. She largely dismissed the transparency concerns raised by critics, telling me many of the 39 hydrogen proposals being considered for funding include confidential business info that can’t be made public yet. She also emphasized that those proposals are tentative, telling me that as more federal funds are doled out, ARCHES will release project details and implement a robust community engagement plan.

“None of the projects are built. Nothing has started yet,” she said.

Galiteva did state explicitly that none of the money will go toward piping hydrogen to homes and business, a SoCalGas priority. As for the broader debate between hydrogen and electric technologies, she highlighted the importance of keeping energy costs down for homes and businesses. One benefit of converting gas-fired power plants to run on hydrogen, she said, is that they would use lots of it, creating economies of scale that would help drive down hydrogen costs for other industries.

Galiteva also pointed to the enormous employment potential, with ARCHES estimating that the full $1.2 billion in federal funding would create 220,000 jobs. Those positions could be especially important for oil and gas workers whose skills may translate better to hydrogen infrastructure than to electric technologies — and who may have a better shot at maintaining their salaries.

That explains why one of the hydrogen coalition’s most vocal supporters is the State Building and Construction Trades Council of California, a politically powerful union labor group that at times has opposed efforts to restrict oil and gas production.

“Having a clean energy industry that doesn’t displace tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of workers is vital to this transition,” said Eli Lipmen, executive director of Move LA, which lists the trades council as one of its top funders.

As the Biden administration hands out money, the hydrogen debate is also playing out at the Internal Revenue Service.

The agency is close to finalizing rules for new hydrogen tax credits, part of President Biden’s climate law. Environmentalists have urged the agency to make those tax credits available only to certain hydrogen projects — those that ensure the fuel is generated with electricity from newly built clean energy facilities, during hours of the day when those facilities are actually running.

To the great disappointment of climate activists, ARCHES weighed in, asking the Biden administration to reject those guidelines. The fewer restrictions on which hydrogen projects are eligible for tax credits, ARCHES said, the easier it will be for California and other states to grow the nation’s hydrogen economy — and ultimately stop burning the fossil fuels ravaging our planet.

Why not take a few extra steps to ensure that hydrogen is produced from clean energy and not from fossil fuels?

When I pressed Galiteva to explain, she essentially argued that California can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

In the long run, the state (and the nation, one hopes) will be powered by 100% clean electricity, meaning we won’t have to worry about where our hydrogen comes from. And although we may not need hydrogen yet, there’s a good chance we will eventually — in large quantities. It’s important to focus now on getting the costs down and learning where the fuel is most valuable.

“The intent is to ensure that this industry succeeds, and we get to our end goals,” Galiteva said.

But while hydrogen could be a crucial climate solution eventually, so far it’s been a dangerous distraction.

As time runs short for getting the climate crisis under control, hydrogen has sowed division and mistrust among the politicians and environmentalists who need to be working together. And it’s given the fossil-fuel industry an easy argument to keep selling us oil and gas while we wait for hydrogen to be ready, even in places where switching to electricity is a far better option.

So how do we move forward, from distraction to solution?

In “Avengers: Endgame,” as the final battle nears its conclusion, Doctor Strange slowly raises one finger — an acknowledgment that yes, this is the heroes’ one chance to win. They’ve got to put it all on the table. The alternative is global catastrophe.

As I said earlier, we have more than one chance in 14 million to defeat climate change. But we’ve got to put it all on the table. We’ve got to build renewable energy infrastructure faster than ever before, from solar farms in the desert to solar panels on rooftops. We’ve got to make climate a top priority at the ballot box, in our dietary choices and in our housing construction.

More than anything, we’ve got to stop fighting and start accepting that no outcomes will be perfect.

When it comes to hydrogen, that doesn’t mean bailing on low-income people of color who have breathed far too much pollution for far too long, or leaving fossil-fuel industry workers out to dry, or allowing oil and gas companies to set the agenda. It does mean finding ways to move beyond our differences and act with the necessary urgency on climate.

Hydrogen won’t solve all our problems. But it should help with some of them. Let’s figure it out, ASAP.

We’ll be back in your inbox Tuesday. To view this newsletter in your web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.