From the archives:: George Michael’s case against fame

- Share via

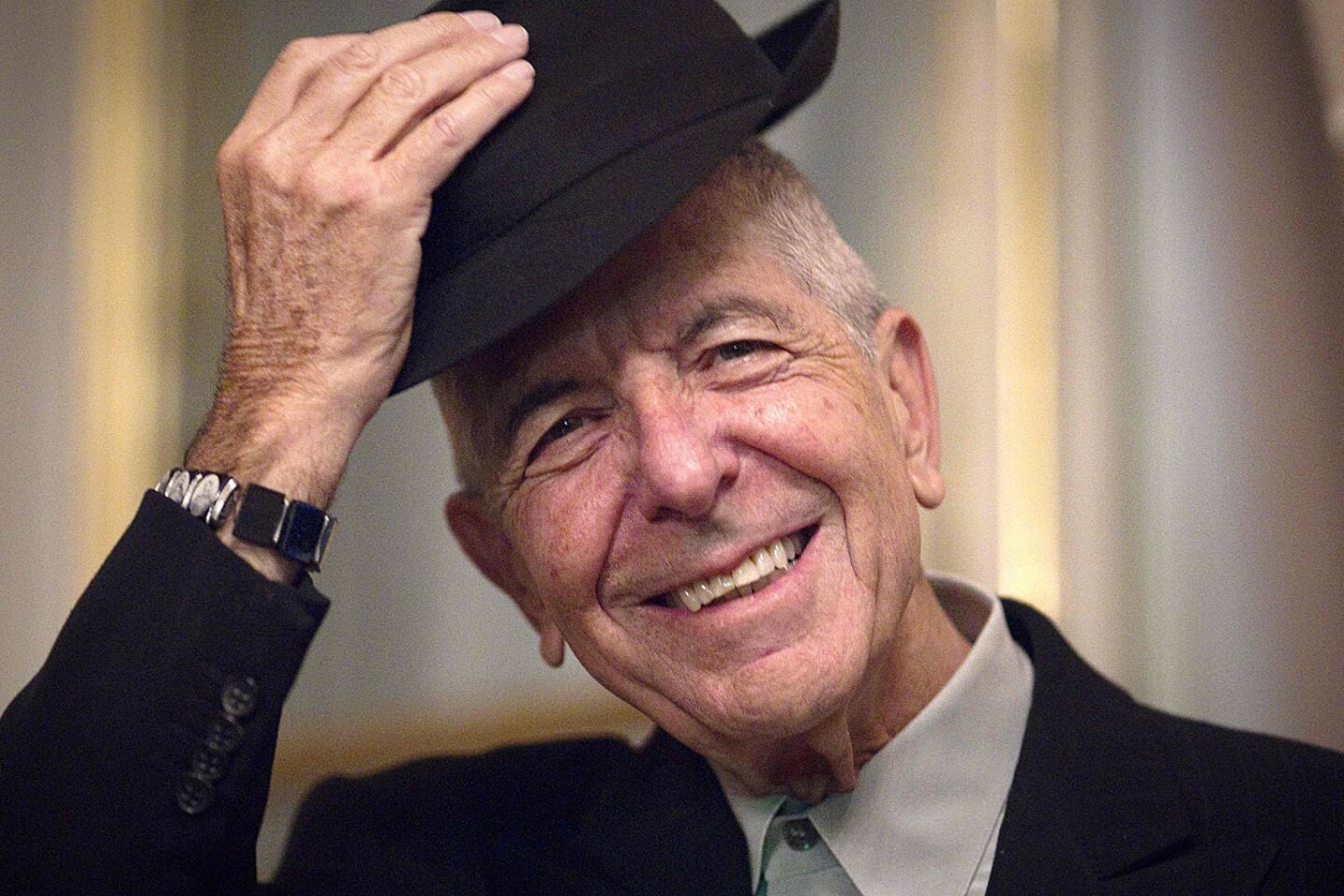

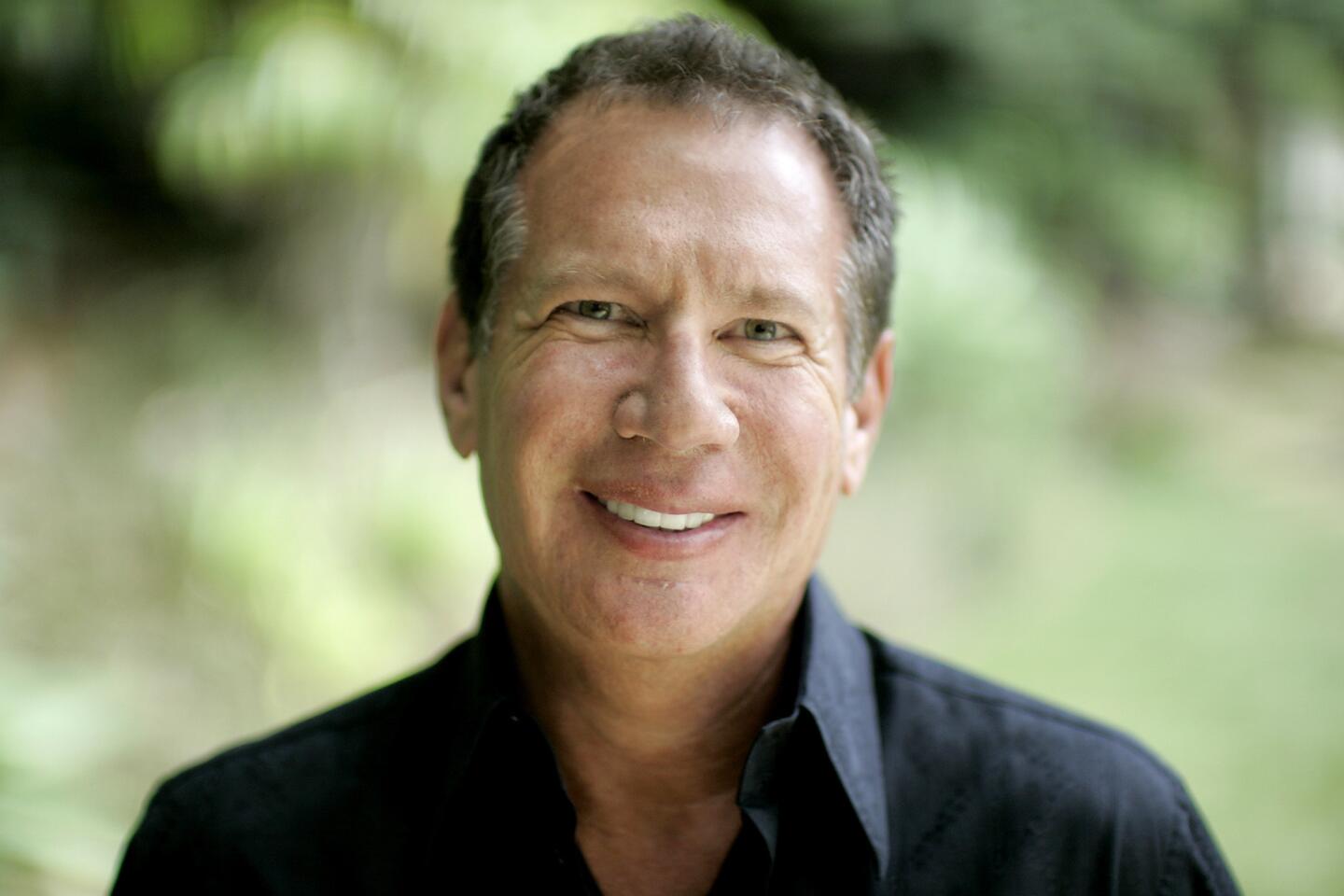

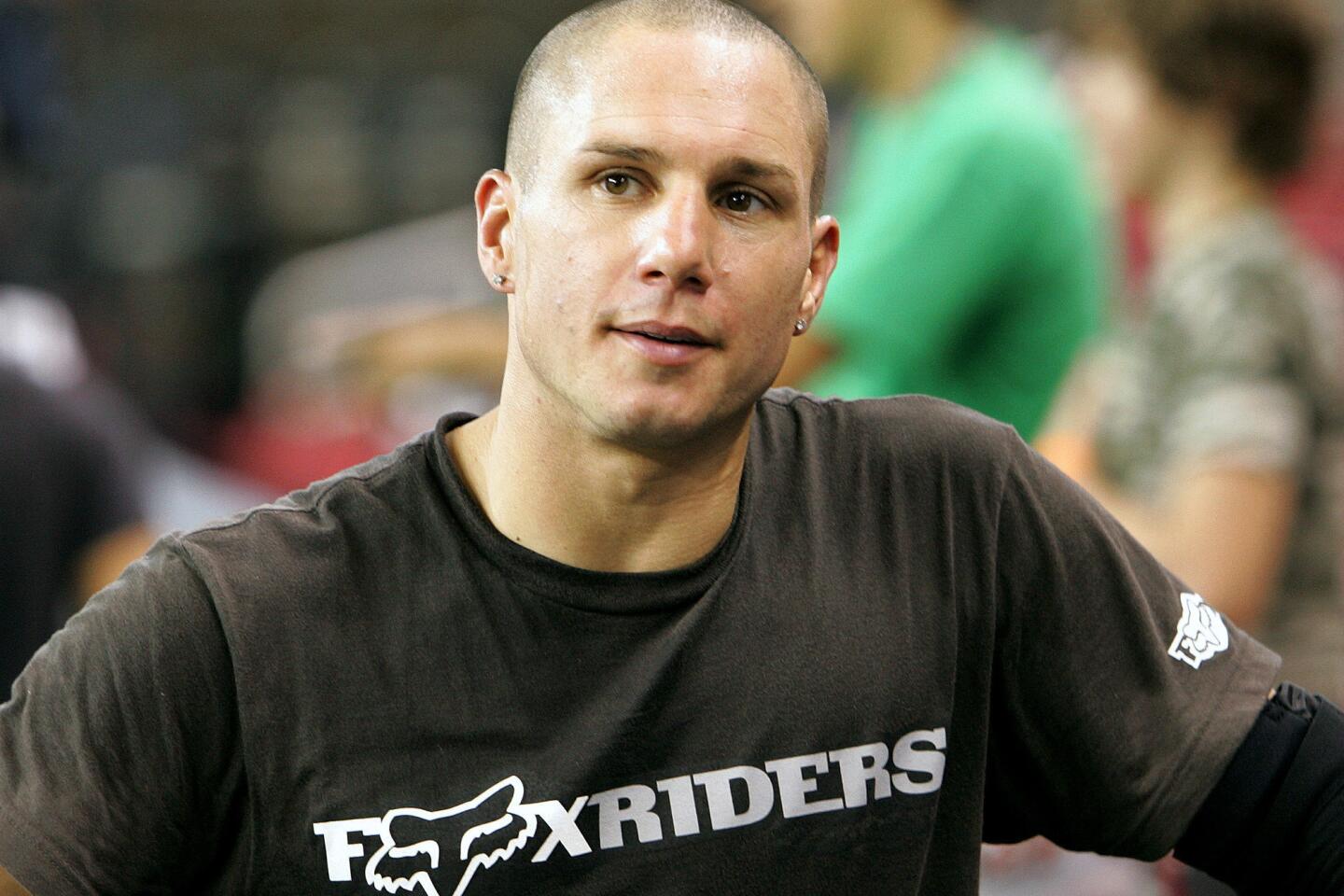

Singer-songwriter George Michael died Dec. 25, 2016, according to his publicist. He was 53. In a 1990 article, he talked about his effort to downplay his celebrity status.

What does George Michael have to complain about?

Here’s an Englishman who came out of nowhere in 1984 to-- wham! --break into the U.S. Top 10 with a catchy, flyweight song, “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” making him a pop star at 21.

Three years later, Michael made the almost unprecedented leap from pretty-boy teen dream to respected adult pop artist. His first solo album, “Faith,” sold more than 14 million copies and won the Grammy for best album of the year. This time it wasn’t just teenyboppers speaking.

So, what’s the problem?

Michael says his pop dreams proved to be a personal nightmare, leaving him on the verge of an emotional breakdown during the early weeks of the 1988 “Faith” tour.

Back now with his second solo effort, “Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1,” Michael is taking potentially revolutionary steps in hopes of reducing the strain of his celebrity status.

In a campaign to downplay his exposure, he’s not making any videos for the new album, and he’s not planning an extensive tour. He may just do a half-dozen or so benefit concerts early next year, and even then he may concentrate on songs by other people.

“It’s quite simple, really,” the singer said, sitting on the beachfront patio of his manager’s Marina del Rey apartment. “I decided that the thing I really enjoy . . . the thing I really needed was my songwriting. I didn’t need the celebrity.”

That sounds fine in theory, but complaints about pressures at the top are commonplace in pop music. Artists frequently argue that videos trivialize a song, and that touring for months at a time works against the creative process, not to mention maintaining a normal lifestyle.

Doing something about these complaints, however, is rare because promotional videos and touring are considered essential elements in building multimillion-unit album sales. They are part of the price of fame.

Videos, in fact, may be a more important sales tool these days than live shows. This is the age of the video star: Madonna, Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul . . . and George Michael.

Despite a lightweight image left over from his days as a member of the duo Wham!, Michael has proved a sharp pop strategist who understood in the early ‘80s that good videos had become a key to success. His sexy image in the Wham! and “Faith” videos most certainly contributed to his appeal.

The question that Michael’s decision poses over the coming months: Can a record maker compete on the charts in the ‘90s without videos and tours? If someone of Michael’s commercial stature and video presence succeeds, other artists may also step away from the video grind. This could lead to a break in video’s stranglehold on the pop marketplace, where the trend is toward signing artists for their video potential rather than their musical abilities.

But even Columbia Records is hedging its bet. It has released, with Michael’s permission, a video of the album’s first single, “Praying for Time,” that consists simply of the song’s socially conscious lyrics printed against a black backdrop--no images of Michael himself.

Another question raised by Michael’s pledge: his credibility.

To a cynical pop world that has heard everyone from Frank Sinatra to David Bowie threaten to say goodby to the microphone, the latest vows of George Michael may seem like little more than a calculated publicity move. After all, he’s obviously still doing interviews.

Michael anticipated the question.

“I’m sure a lot of people are going to believe all this is just some sort of gimmick . . . just another way to stir interest,” Michael said in what was the first of three U.S. newspaper interviews he had agreed to do--with the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times and USA Today--in connection with the release of the album on Tuesday.

“ ‘But I’m also sure that most people find it hard to believe that stardom can make you miserable. After all, everybody wants to be a star. I certainly did, and I worked hard to get it. But I was miserable, and I don’t want to feel that way again.”

George Michael may be praying for time in his personal life and in his new hit single, but he could also use something a little more down-to-earth: a good sunscreen lotion.

Yes, Michael, a man known in the ‘80s for a tan so perfect that some speculated he somehow dyed his skin, had a shiny sunburn on his nose and forehead as he sat down for the interview.

Michael smiled when asked about the skin-dye rumors.

“I used to just sit out in the sun all the time because I loved it, so I always did have a tan,” he said, brushing self-consciously at his bright, glowing nose. “But now I get bored doing that. I start getting restless . . . and, besides, I’m starting to burn. That’s something that never used to happen.”

The singer, who had picked up the burn while riding a bike around the neighborhood that morning, was dressed casually in a white T-shirt and shorts topped off by a Lakers cap. He nibbled at some vegetables and other snacks on a table in front of him.

Michael, who has what he describes as a “vacation/investment” house in Santa Barbara but lives chiefly in London, seemed unusually at ease for someone who says he doesn’t enjoy interviews.

He didn’t act overly friendly or overly dramatic. More than anything, he seemed to be taking care of a final chore before going on vacation--and that’s what he may consider his break from video work and media exposure to be.

The sunburn added a welcome human touch to a persona that has often come across as a touch calculated.

But why the final round of goodby interviews? Why not just drop out of sight?

“I think it was important, not really for the people who have always doubted me, because they’ll still doubt me,” he said. “I did it for the people who have supported me. I think they are owed some sort of explanation.

“But it won’t really be goodby to my way of thinking because they’ll still have the most important part of me, which is the music. The rest--the whole video image--was just a creation . . . something I wanted in the beginning because of all the childish fantasies about (craving) love and attention.

“The truth is, it all got much bigger than I ever imagined--and much harder to control. Ultimately, I wasn’t comfortable with that kind of visibility and power. Once I became more confident as a writer, I realized I didn’t need all that other bolstering.”

A rrogant is a word that was often applied to the handsome young singer during his early days as the leader of Wham!, the English duo whose hits, besides “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” included “Everything She Wants” and “I’m Your Man.”

And it’s easy to understand why, when you see such quotes as this one from a 1988 interview with the English pop magazine Q:

“People have always thought my career has been incredibly calculated and premeditated but it runs along pretty well parallel lines with most people’s careers. It’s just that the decisions I have made personally have been much more . . . correct.”

For a while, everything the pop sensation did was indeed correct--and blatantly calculated, a trait that makes some observers suspicious now about Michael’s true intentions. Two other tags applied to Michael more recently seemed more appropriate: articulate and down-to-earth .

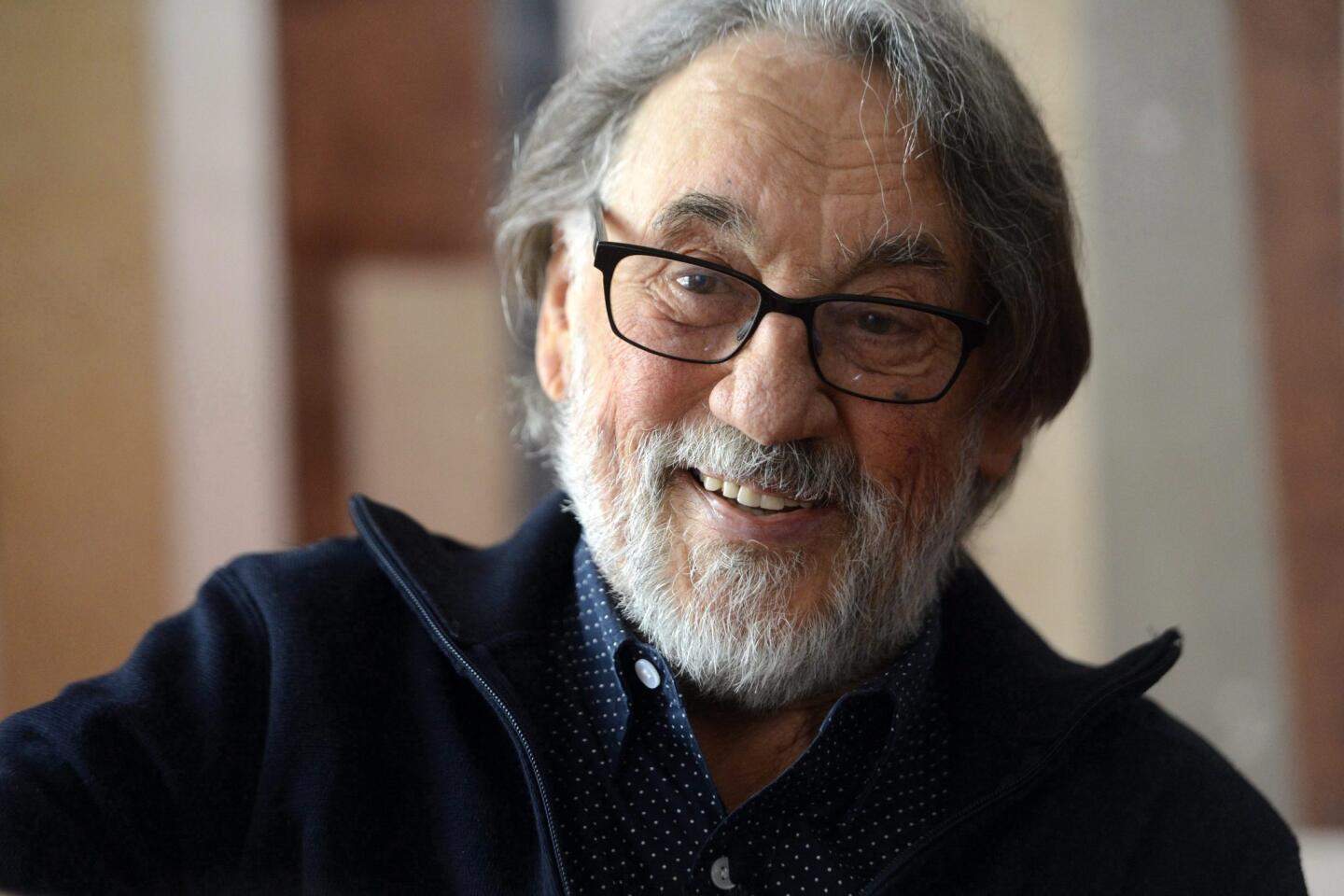

The way he tells it, George Michael was born to be a pop star. It’s as if nothing else really mattered during his childhood. Even the name was part of the pop creation.

Michael didn’t shy away from questions about his childhood in various London suburbs, but almost every answer involved music. “I wanted to be a pop star since I was about 7 years old,” he said flatly.

Born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou in London on June 25, 1963, Michael is the son of a Greek father and an English mother. One of three children, Michael, whose father operated a restaurant, described his upbringing as middle-class and his childhood as “stable, happy.”

Young Georgios did well in high school, where he was especially fond of English and art. But his passion was music. He loved listening to records, especially Elton John, Stevie Wonder and Queen. He didn’t just listen to them--he dissected them. He was fascinated by song construction and how arrangements were pieced together.

But Georgios didn’t think about pursuing music until he met Andrew Ridgeley, a schoolmate who shared his love for music and his hunger for fame.

They formed their first band, a ska-influenced outfit called the Executive, in the summer of 1979. The group played a few dates and recorded a two-song demo that they sent to record companies, but it was rejected.

Undaunted, the pair continued to write songs together while working at various odd jobs. Excited by the energy of the British dance-club scene, they recorded another demo tape. This time the tape--featuring such original tunes as “Careless Whisper” and “Wham! Rap”--led to a record deal in 1982.

Unusually headstrong, George Michael--as Panayiotou began calling himself around this time--rejected attempts to turn the duo, called Wham!, into a traditional rock band that would follow the normal club circuit in England.

In “Bare,” an autobiography recently published in England, Michael explained his thinking at the time. “We were very aware of how the music business was changing, how you could suddenly reach more people with a video on MTV than with a 90-date tour of the States. We knew it was the future . . . that for the first time you didn’t have to be a band.”

About those days, Michael recalled during the Marina del Rey interview, “I was shocked at how little most people seemed to know in the record business and how willing they were to listen to anyone who seemed to have a firm idea about what was needed.”

Michael most certainly had a firm idea--and it worked. He made it from high school to the top of the British charts in less than a year.

America was next.

At first, everything was wonderful in Wham! The success. The screaming fans. And Michael fueled the frenzy. He danced around the stage in tight shorts and flashed the brightest smile since David Cassidy.

It was a time of flamboyance in pop . . . the start of the video age. Such rivals as Duran Duran and Culture Club were equally flamboyant, but Michael and Wham! outdistanced them all in England, coming up with slick and generally disposable pop that also had an undeniable edge of craft.

There were doubts about Wham! at every step in its U.S. assault. At first, record company sharpies in this country said that the group’s teen appeal wouldn’t translate well here. They were wrong.

“Wake Me Up . . .” and “Careless Whisper” both went to No. 1. Other insiders raised their eyebrows in 1985 when Wham! tried to sell out stadiums. Wrong again.

However, Michael, who emerged as the heartthrob and creative center of the group, knew he had to get away from the teen-ish Wham! image and sound if he were to have a long career. So, the inevitable breakup.

“I think one of the things that people loved about Wham! was the sense of friendship we projected, and that friendship was genuine,” Michael said. “Andrew brought a lightness, a fun to the whole thing.

“But he knew that Wham! was a finite thing and that it was just a question of when. We agreed very early that we wouldn’t let it burn out . . . that when it got to a certain height, we’d stop it, and we did.”

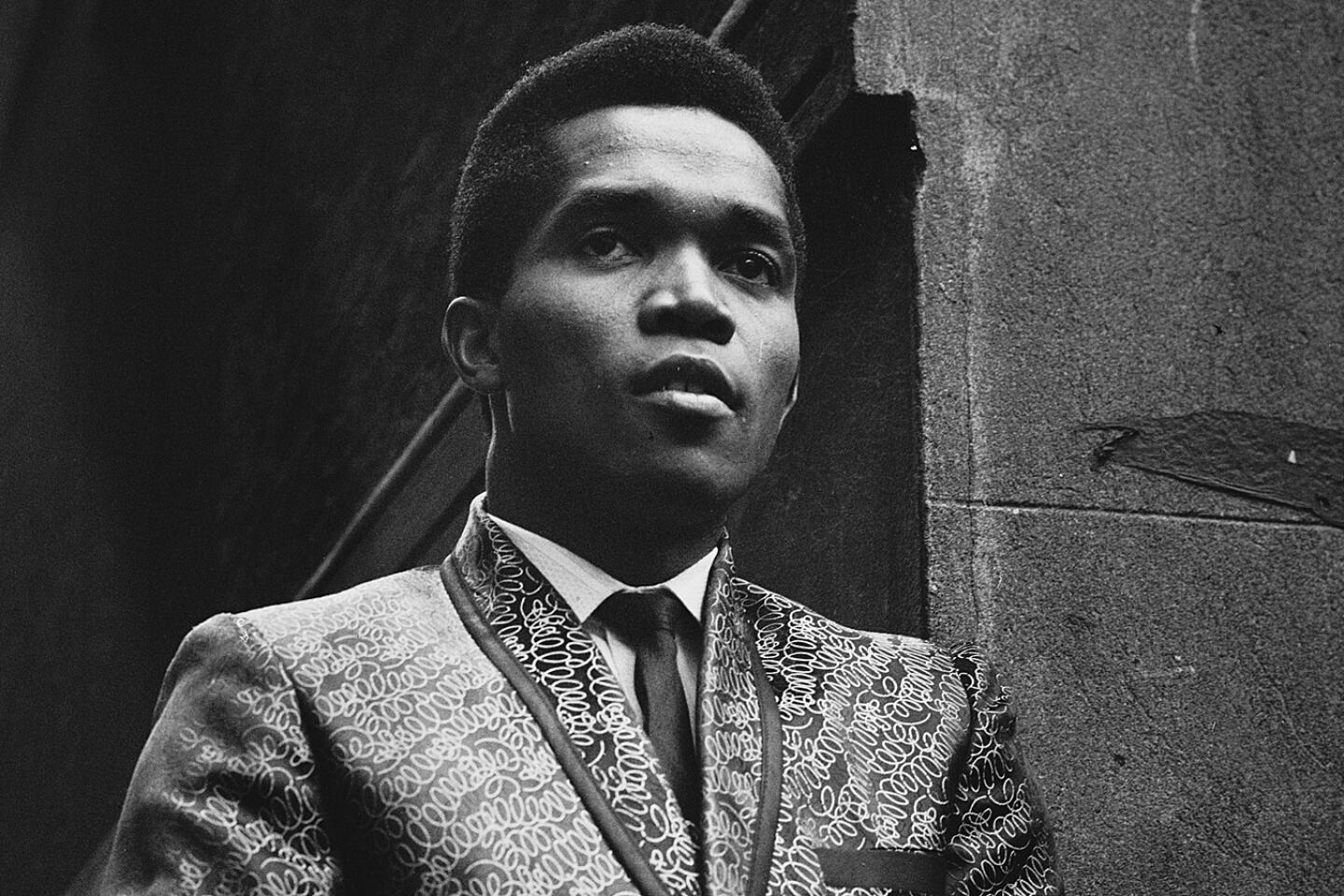

Several small moves helped establish Michael’s solo credibility, including a well-received appearance on a Motown TV special, where he sang with his childhood idols Stevie Wonder and Smokey Robinson. Another was a hit duet, “I Knew You Were Waiting for Me,” with Aretha Franklin.

Yet “Faith” was his biggest test.

The album was designed to both hold on to the legion of Wham! fans, yet exhibit a new maturity of songwriting that would attract an older following. It succeeded remarkably well.

Videos for songs like the sensual, aggressive “I Want Your Sex” and the catchy, rockabilly-tinged “Faith” were MTV smashes, while such numbers as the dark, disillusioned “Hand to Mouth” suggested a deeper dimension.

If the album’s success was liberating, the “Faith” tour proved a horror show--and led to Michael’s dramatic decision to step out of the normal pop guidelines.

The singer’s mood darkened slightly as he recounted the “madness” of the early days of the 1988 “Faith” tour.

“Actually, I can remember the exact moment that I decided I must change my life,” he said.

Naively, Michael had thought he would be able to leave the frenzy behind when he stepped out of Wham!

“We (opened) the ‘Faith’ tour in Japan, which was fine because they are reasonably quiet, and they listened to the music. But then we went to Australia, and the roof came off the first place we came to. The screaming . I thought, ‘God, it is happening all over again . . . I’m not going to have a chance to really sing,’ ” Michael recalled, reliving his displeasure at the clamor and the huge sites. “And I realized I had to do it for 10 months.”

“It was devastating,” he said of the “Faith” tour experience. “I was hugely temperamental, and I had a major problem with my throat, which didn’t help at all because people thought that was just part of my being temperamental, and it wasn’t. . . .

“It was a combination of things, including being on the road for that long. I’m someone who really needs a center. I was very close to what I could call a breakdown until I finally took a month off, because of (throat) surgery, and sorted it out. I made the decisions that I’m acting on.”

Why does the video star now hate videos?

Two reasons. Chiefly, they violate Michael’s sensibilities as a songwriter, but he also has grown uncomfortable in front of a camera. (He refused to have his photo taken for this article.)

“Videos force you to think of (songs) in a certain way rather than being free to interpret them however you like,” he said. “Some songs are very good video songs . . . ‘I Want Your Sex’ and ‘Faith’ . . . but very little in this album is right for video.

“When you are trying to express things with metaphors and much more subtlety, that’s when you are doing yourself a disservice by making a video. I don’t want to say I won’t do another video ever, but I won’t do one for the foreseeable future. If my life goes the way I want it to, I would like to never step in front of a camera again.”

On that issue, Michael added, “I don’t know. It’s strange. At some point in your career, the situation between yourself and the camera reverses. For a certain number of years, you court it and you need it, but ultimately, it needs you more and it’s a bit like a relationship. The minute that happens, it turns you off . . . and it does feel like it is taking something from you. I don’t know how to explain it any more than that. It is like taking something you don’t want to give.”

Beyond the question of videos and interviews, photo sessions and tours, the real challenge facing George Michael at the start of the ‘90s is the depth of his artistry.

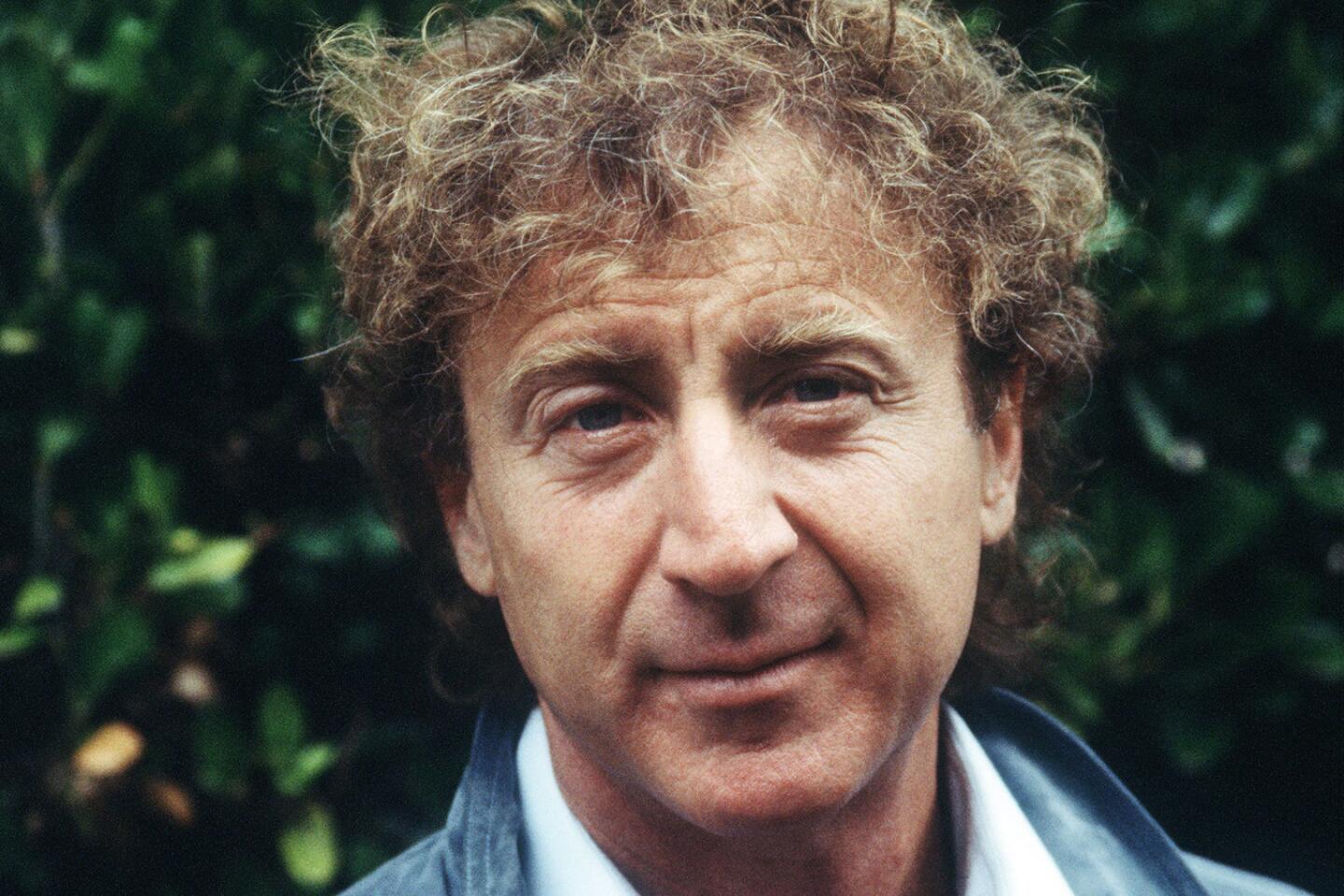

Even with his fame and the “Faith” Grammy, there is still an anonymous quality to Michael’s music up through “Faith.” Much like Billy Joel, he has a sense of craft as a writer, but he has yet to establish an original or arresting vision that gives his music a distinctive, significant edge.

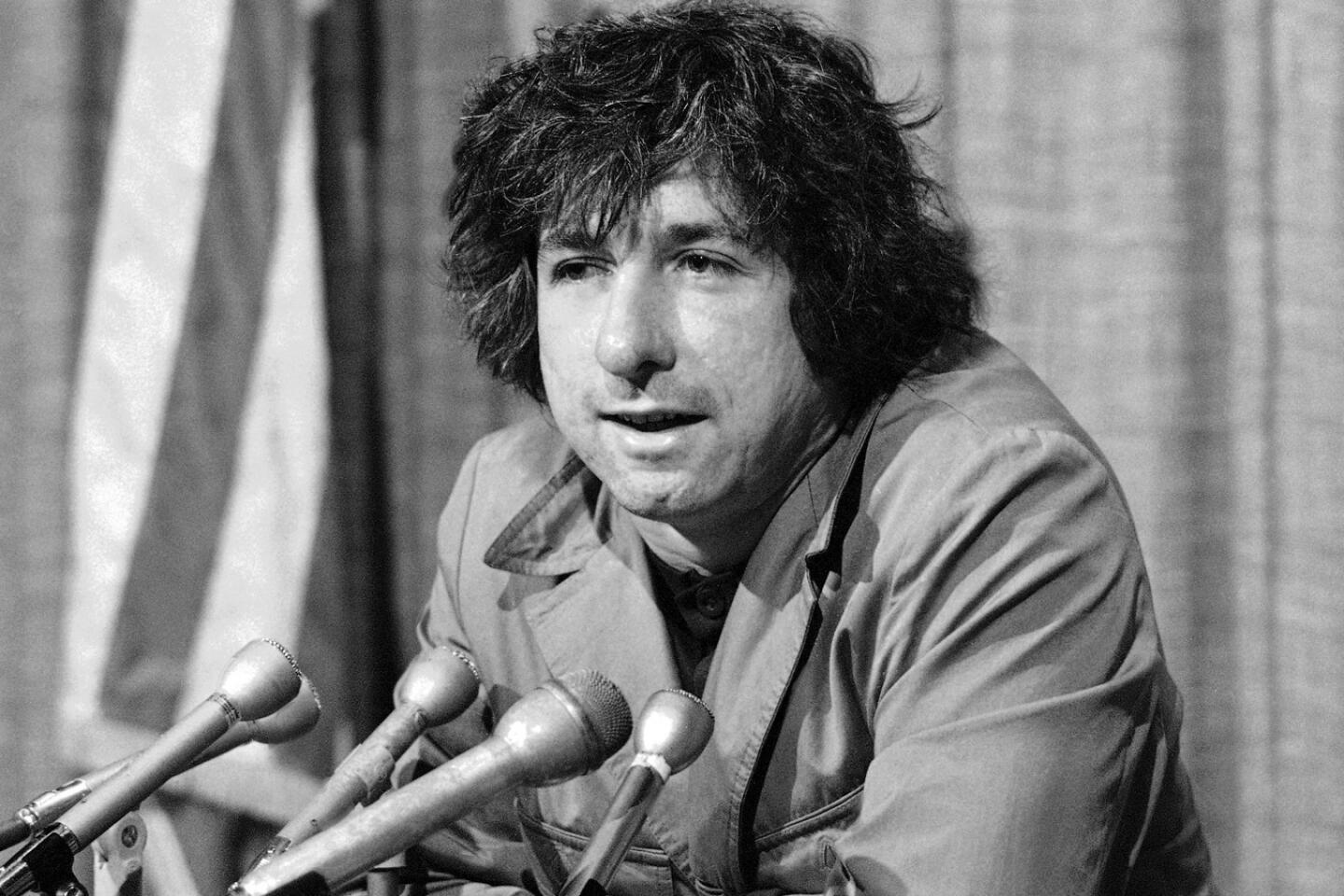

Though he was an early bloomer as a pop star, he is getting something of a late start as a serious writer. By 27, Bob Dylan had already written “Highway 61 Revisited,” the Beatles had released “Rubber Soul,” Bruce Springsteen had recorded “Born to Run” and U2 had delivered “The Joshua Tree.”

Michael appears to recognize that challenge. He said he hopes staying off the road will give him more time to work on his writing, and that he has begun to explore writers of such extraordinary vision as Dylan, Joni Mitchell and the Beatles. He also was planning to do an album of dance tunes for early next year, but now may continue to write in the more serious vein of “Listen Without Prejudice.” He does exhibit more personal revelation in key songs on the new album (see adjoining review).

One encouraging sign of independence is that Michael isn’t going along with the flattering comparisons of his new single, “Praying for Time,” with John Lennon’s idealistic “Imagine.”

In pointing out that the socially conscious song has attracted the most radio airplay of any single since 1985’s “We Are the World,” USA Today described its tone as similar to that of “Imagine.”

“It’s not like ‘Imagine’ at all,” Michael said. “It’s much more negative. I’d like to say things are bound to get better, but I don’t really believe it. The song is my own way of trying to justify people’s actions and their selfishness, I suppose.”

Sample lyrics from “Praying for Time”:

And it’s hard to love, there’s so much hate

Hanging on to hope

When there is no hope to speak of

And the wounded skies above

Say it’s much too late

So maybe we should all be praying for time.

Michael leaned back in his chair and shrugged.

The world, he said, seems like a “place where things are running out of time. Everything is getting more violent. You need more protection all the time and it has gotten so bad that people’s general attitude is, ‘What the hell? I think I am going to hold on to what I’ve got.’ The key line for me is the one about it’s hard to love, but there’s so much to hate.

“The only real copout in the whole thing is the line about praying for time. Maybe I’d think that if I had children . . . I’d want to reach for straws. But I don’t think that will make the slightest difference. I’m very much fatalistic.”

Besides making more music, Michael hopes to use the extra time to grow on a personal level. Relationships, he said, have been a problem for him.

“Well, they really haven’t been difficult in the last few years, because I just haven’t had one,” he said. “I have been pretty disastrous with relationships, and I have kind of decided I was going to give myself a rest from them for a while.”

While Michael’s goals about concentrating on music and personal growth rather than show-biz marketing sounds good, Michael is bound to feel anxious if album sales slip substantially.

There’s not a great danger in releasing the first single from an album without a video because the momentum from the last album will cause large numbers of fans to buy it.

But the real test of an album’s commercial strength normally comes three to six months after its release--when videos for a second or third single are released to keep public interest high.

Tommy Mottola, president of CBS Records, is thrilled about the strong initial radio response to “Praying for Time,” the album’s first single. But he’s also clearly a bit anxious about the singer-songwriter’s decision not to do promotional videos.

“I think you’ll have a lot of disappointed fans because there is no video, but when they get to understand his point of view and hear the record, I don’t think there will be any problem,” he said, trying to put the most optimistic slant on the situation in a phone interview from his office in New York.

“He explained that he wants to do more work, more songs, more albums rather than have his time diffused with touring and doing videos and things that really rub him the wrong way. And if doing those things are going to cause that kind of a reaction in an artist, then what’s the point of doing them?”

Bob Merlis, vice president of publicity for rival Warner Bros. Records, called Michael’s move a “noble experiment,” but said he thinks the importance of video is so firmly established in the pop world that it is difficult to imagine anything dislodging it.

“I can’t see a flood of artists following Michael’s lead even if his album matches the sales of ‘Faith,’ ” Merlis said. “Besides, Michael is a special case. He’s already a multi-platinum artist who has a following. It’d be different if he were starting out. More than a test of the importance of video, I think the move may be a test of loyalty of Michael’s audience.”

Isn’t Michael worried about sales?

“I’m sure everyone (at CBS) is terrified that all this is going to sabatoge the album,” the singer said. “But I honestly feel I am in a very privileged position because I have the luxury of knowing that simply because of the size of the last album, this album will be heard . . . regardless of whether I make videos or not.

“I also have enough faith in the songs to believe that if people hear the album, enough will like it. I don’t necessarily believe it will sell 14 million copies. I’d be very surprised if it does, but I do believe it is a much better album, and I think that in itself will compensate for part of the lack of presence.”

Reflecting on the gamble involved in his experiment, Michael added:

“I can’t lose because I know what the alternative is. I’m not stupid enough to think that I can deal with another 10 or 15 years of major exposure. I think that is the ultimate tragedy of fame. . . . People who are simply out of control, who are lost. I’ve seen so many of them, and I don’t want to be another cliche.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.