Vilmos Zsigmond, Oscar-winning cinematographer, dead at 85

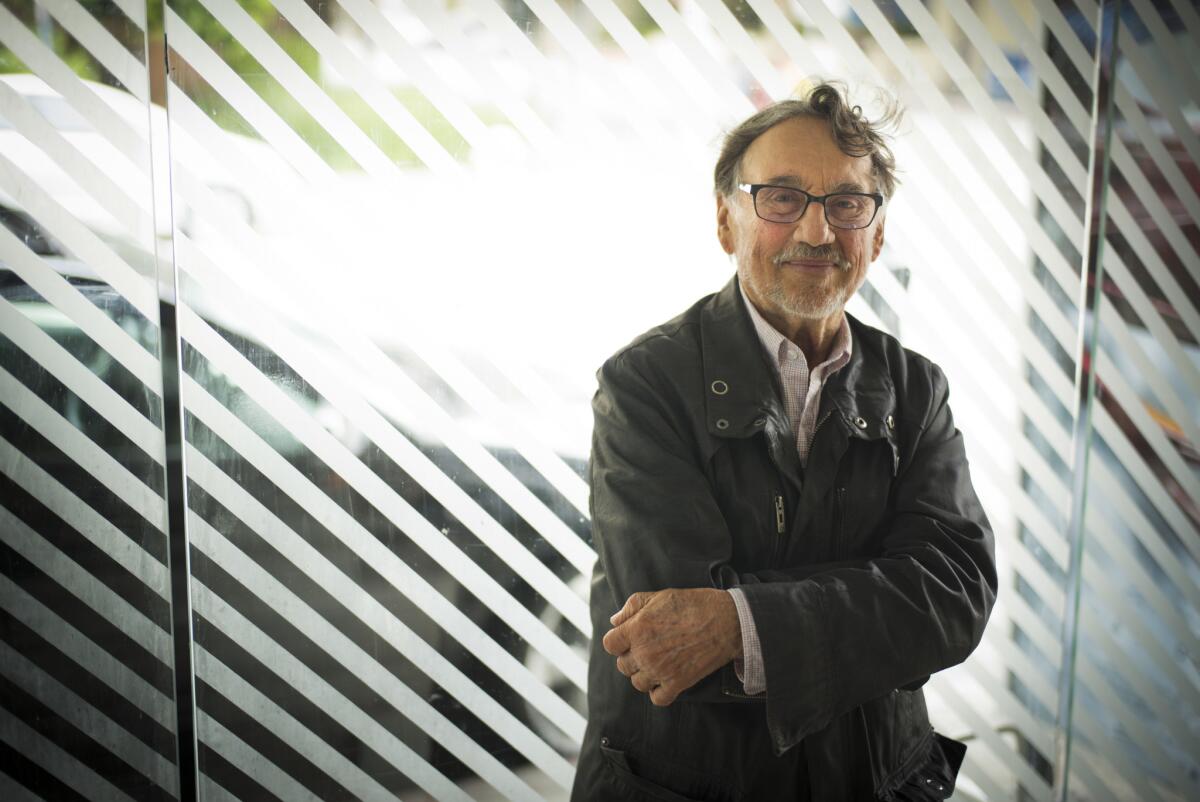

Award-winning cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond died Jan. 1. Here, he poses in San Francisco, where he kept a part-time residence.

- Share via

Oscar-winning cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, revered as one of the most influential cinematographers in film history for his work on several classic films, including “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “The Deer Hunter,” died Friday. He was 85.

The Hungarian-born Zsigmond died in Big Sur from “a combination of many illnesses,” said his business partner Yuri Neyman.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Among Zsigmond’s most noteworthy achievements was his Oscar-winning cinematography on 1977’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” written and directed by Steven Spielberg. In a 1998 interview with The Times, Zsigmond revealed that making that film was difficult because “we were breaking new ground.”

“Before ‘Close Encounters,’ there were some space movies about spaceships, but nothing really that great technically that we could follow,” he said. “So we had to invent.”

Part of that process involved managing Spielberg’s requests for bigger lighting effects: “He kept always telling me, ‘I want to see an incredible amount of light coming out of the spaceship.’ So we had to figure out a way to do that.”

“Close Encounters” was nominated for seven other Oscars and became one of the films that established Spielberg as a major force on the film landscape.

Zsigmond received three other Academy Award nominations during his more than five-decade career. He was nominated for 1978’s “The Deer Hunter,” 1984’s “The River” and 2006’s “The Black Dahlia.” He won an Emmy for the 1992 miniseries “Stalin,” and was nominated for 2001’s “The Mists of Avalon.”

He continued to work well into his later years, shooting several episodes of the comedy “The Mindy Project” from 2012 to 2014 as well as many other films that have yet to be released.

In a phone interview with The Times, Neyman, who, along with Zsigmond, co-founded the Global Cinematography Institute, remembered his friend’s influence on the industry.

“He taught people how to look and think differently,” Neyman said. “He was unique at a time when he was just in independent cinema, before all the awards. He changed how people view cinematography.”

Steven Poster, president of the International Cinematographers Guild, agreed. The group in 2003 voted Zsigmond one of the 10 most influential cinematographers of all time.

“Vilmos was an inspiration and mentor to many of us,” Poster said in a statement on behalf of the organization, to which Zsigmond also belonged. “We all knew what a giant he was as an artist at the time. But working up close with him, I also learned about perseverance and an obligation to the story.”

Zsigmond was born June 16, 1930, in Szeged, Hungary. As a student studying cinema at the Budapest Film School, he began his career documenting the Hungarian revolution of 1956.

He and fellow classmate Laszlo Kovacs hid a borrowed 35-millimeter camera from their school in a shopping bag with a hole cut out for the lens and shot footage of the Soviet invasion. Armed with about 30,000 feet of film hidden in potato sacks, Kovacs and Zsigmond fled across the Austria-Hungary border, which was patrolled by Russian soldiers.

They arrived in the United States as political refugees in early 1957 and sold the footage to CBS for a network documentary on the revolution narrated by Walter Cronkite.

Kovacs established his own distinguished career, earning accolades for photographing several films, including “Easy Rider” and “New York, New York.”

In a 2005 interview with The Times, Zsigmond discussed the importance of the cinematographer’s role in Hollywood.

“The cinematographer helps to tell the story in a visual way,” he said. “I don’t really depend on dialogue. I consider film a visual art, and for me, telling the story visually is more important than telling the story with words and dialogue.”

Follow me on Twitter: @TrevellAnderson.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.