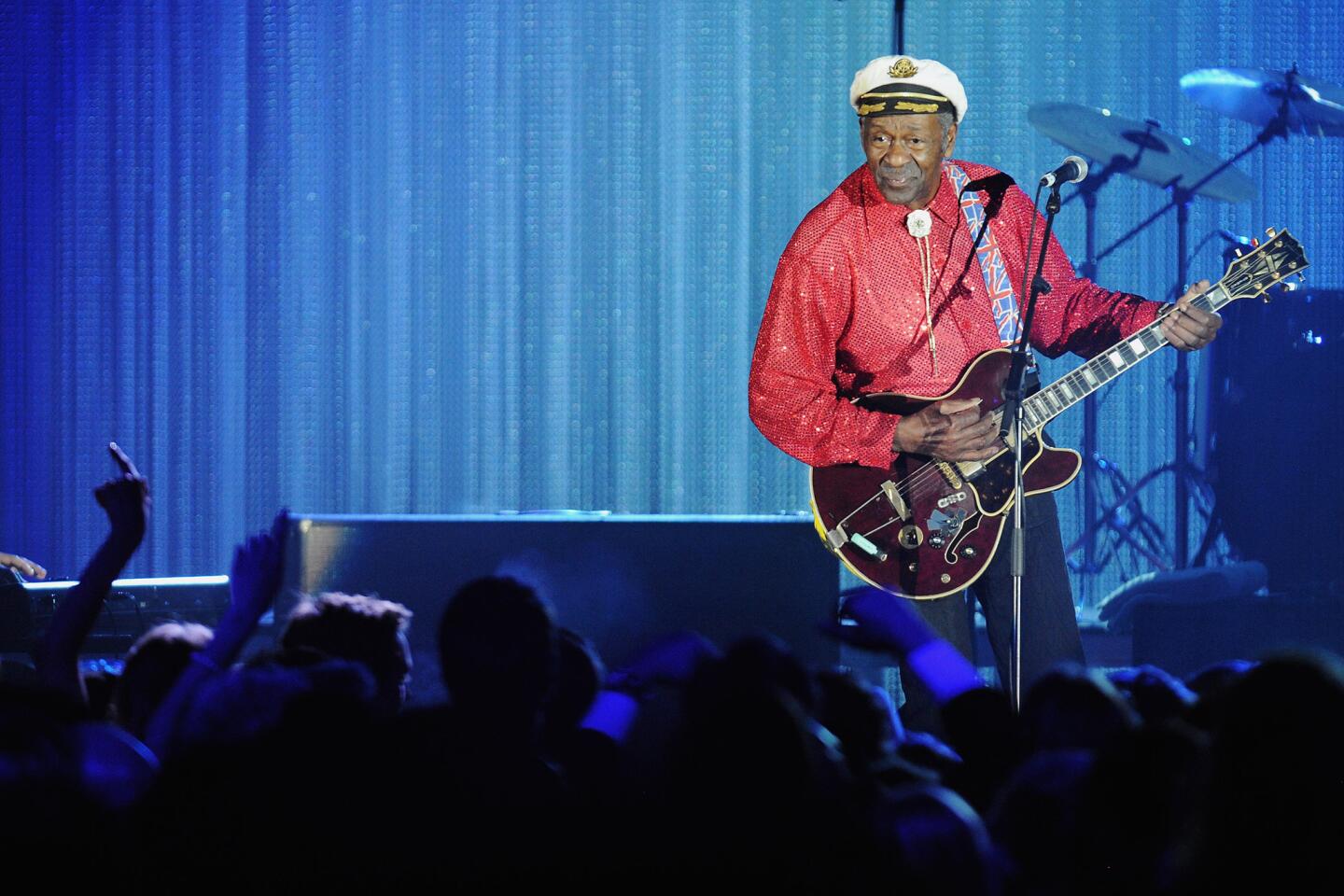

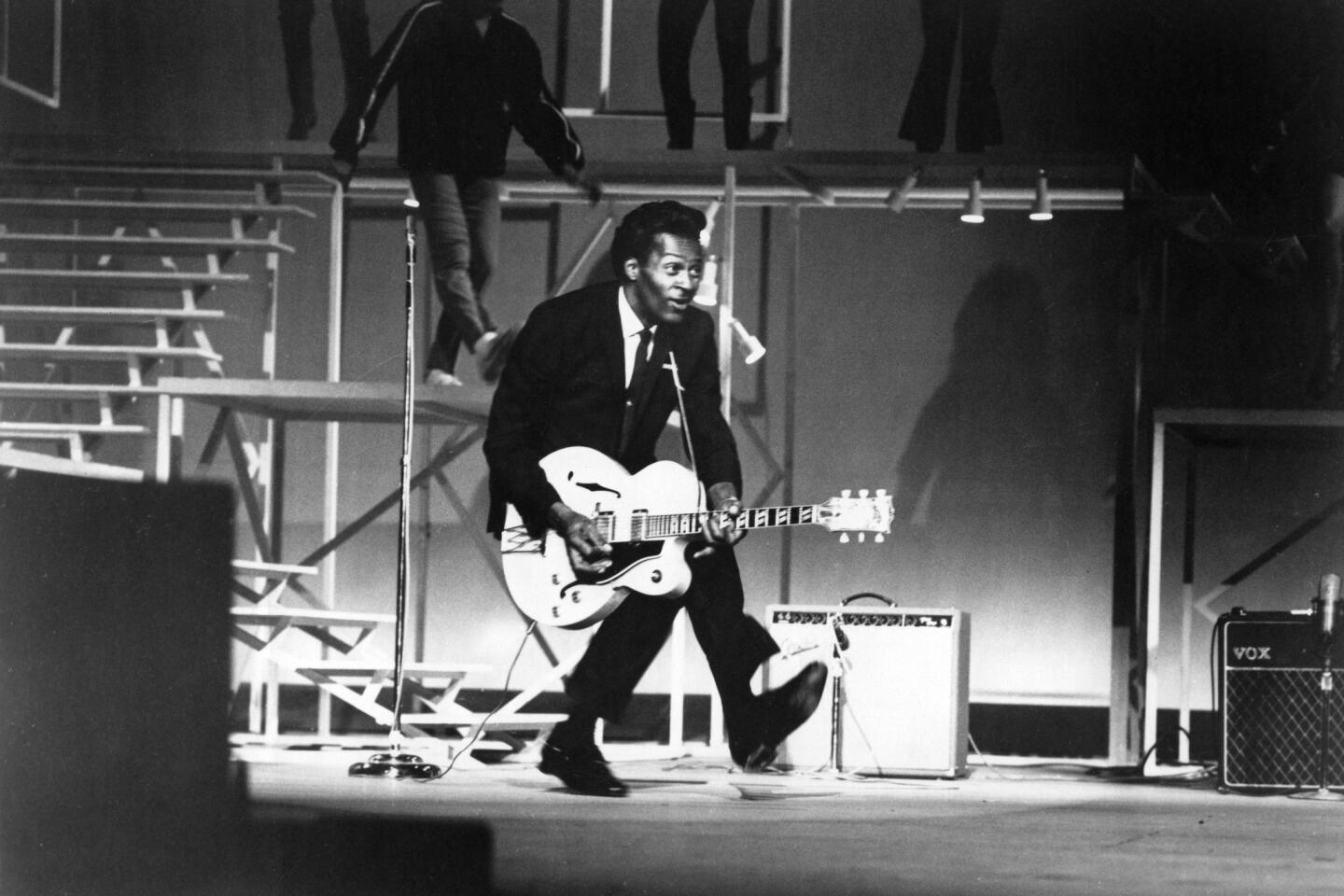

From the Archives: Chuck Berry talks music, race and his ‘difficult’ reputation

- Share via

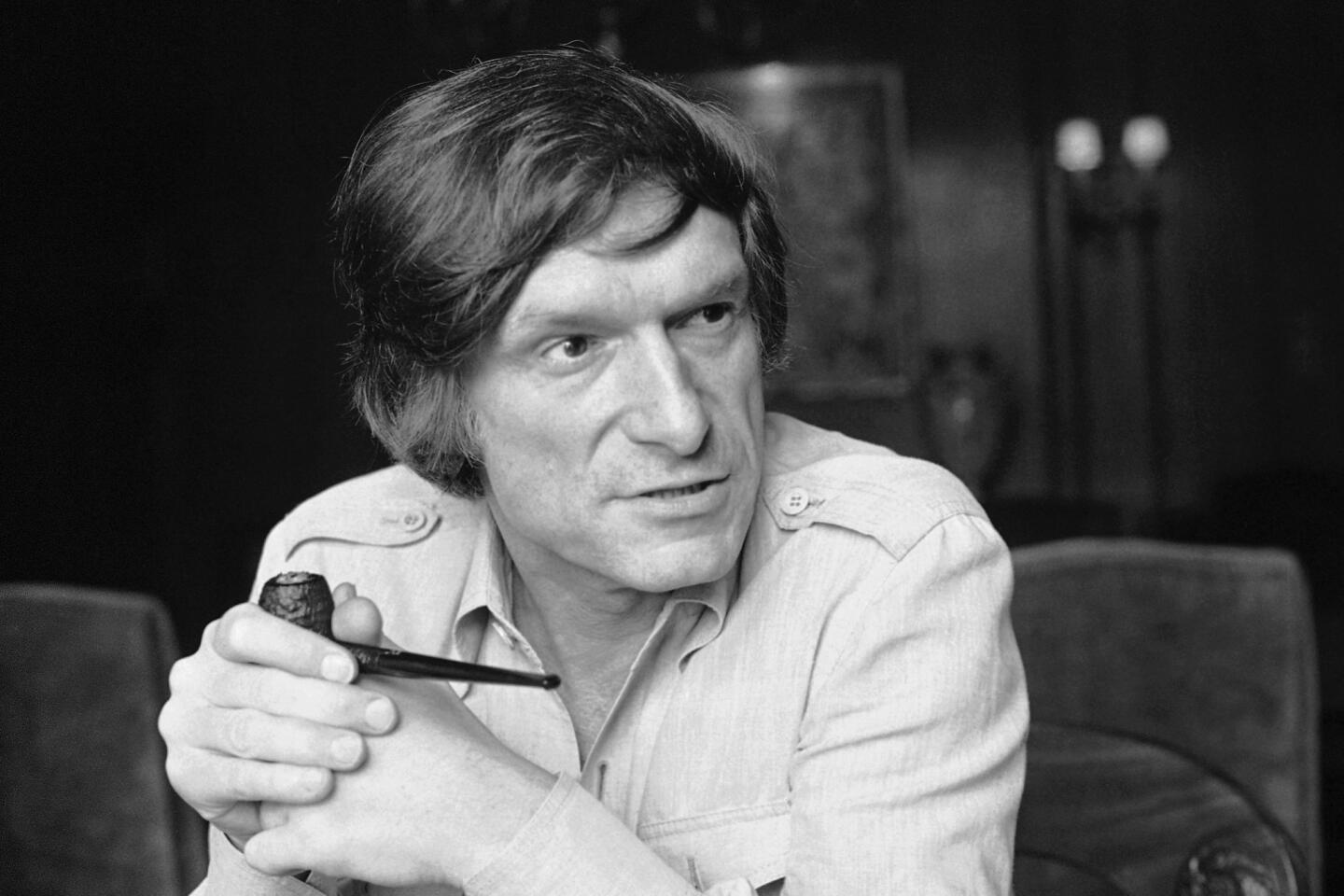

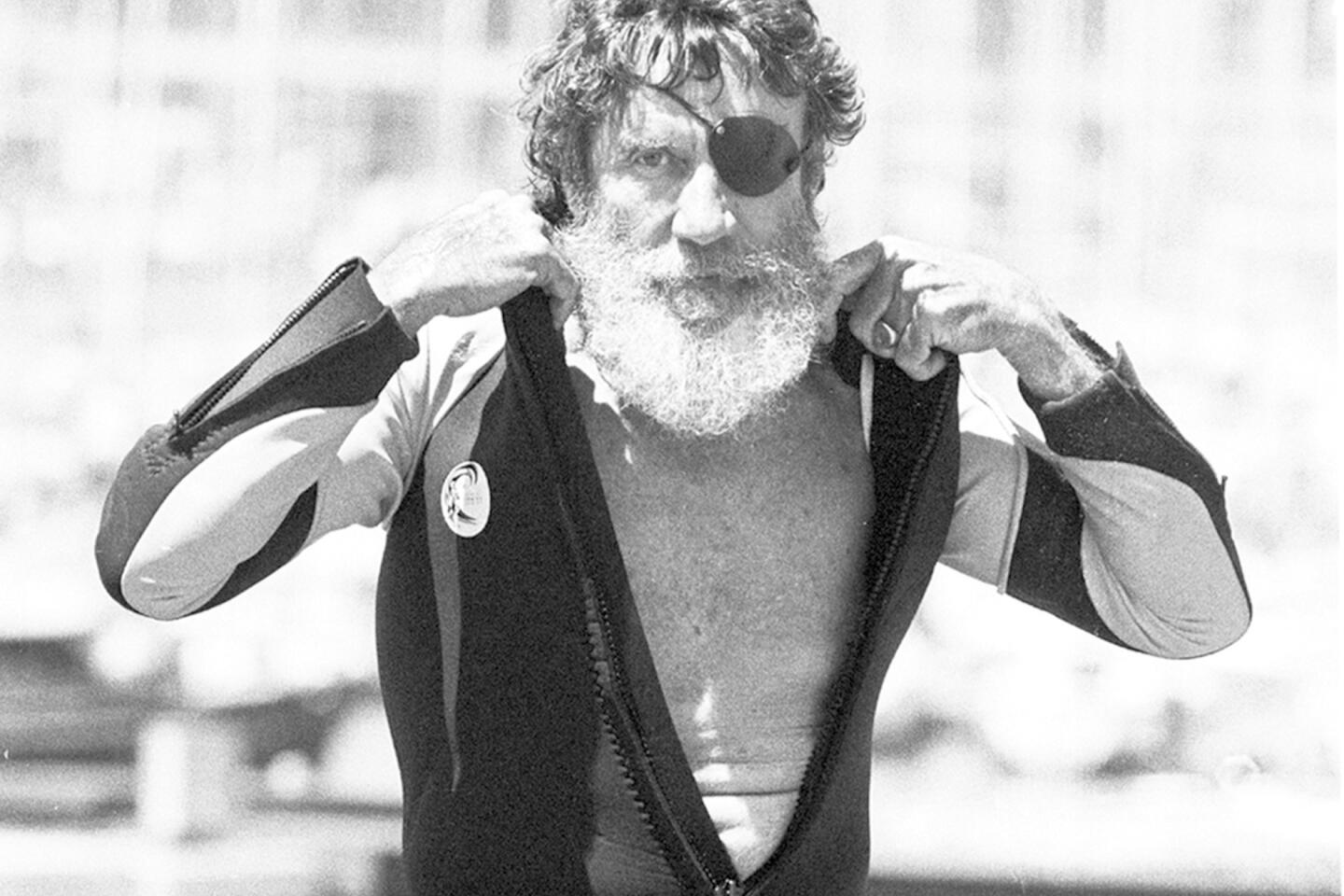

Reporting from St. Louis — Editor’s note: Chuck Berry died March 18, 2017 at the age of 90. This article, in which Berry sat down with Times music critic Robert Hilburn to talk about his musical influences, “difficult” reputation and encounters with racial prejudice throughout his career, was first published on Oct. 4, 1987.

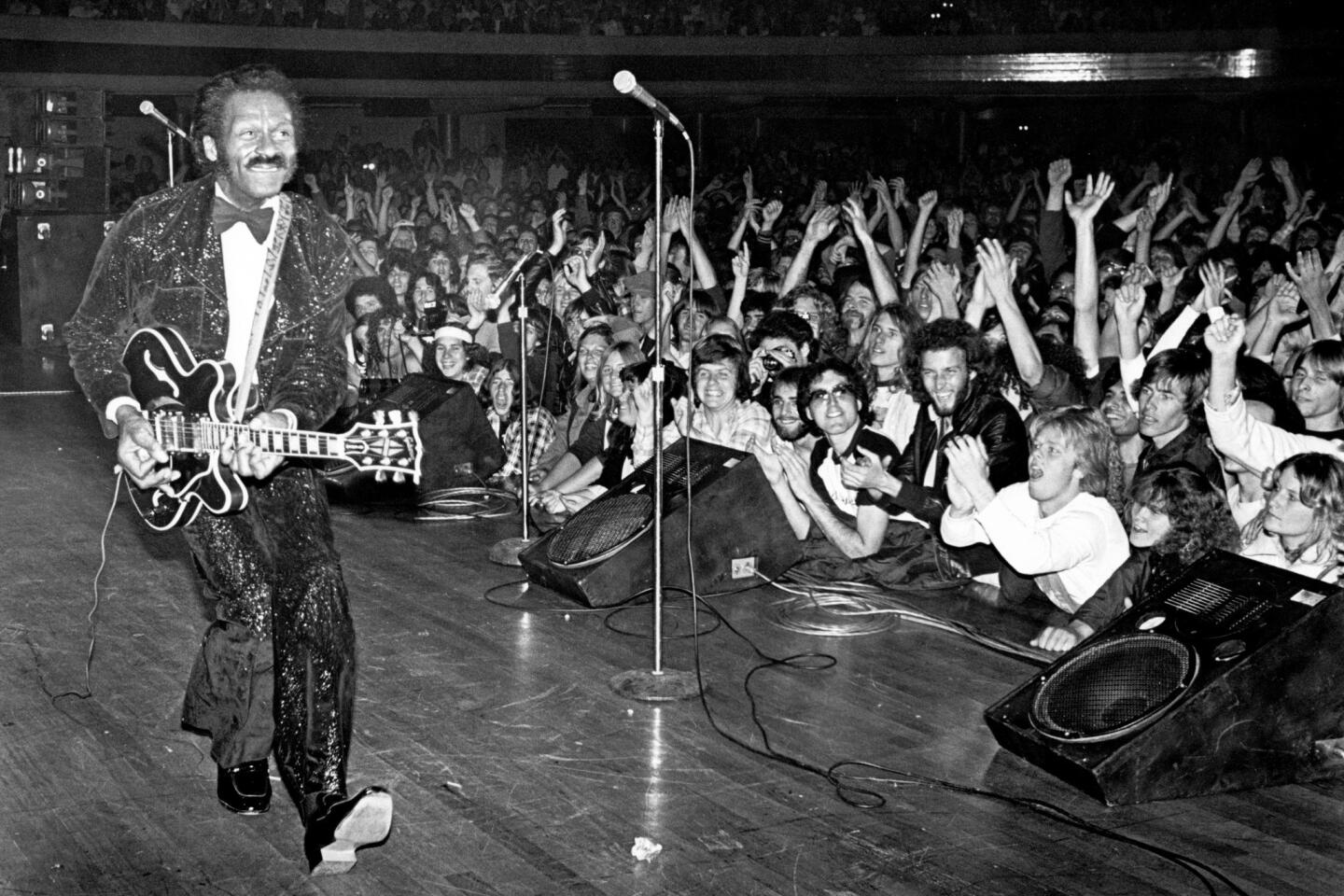

Chuck Berry has been prized by rock musicians and fans for four decades as a symbol of the revolution that chased away Big Band music and other dull adult sounds.

In hits like “Roll Over Beethoven” and “Sweet Little Sixteen,” Berry reflected the frisky independence and innocence of ‘50s teens with such unwavering accuracy that they remain anthems of the era.

You know my temp’rature’s risin’

and the juke box blowin’ a fuse.

My heart’s beatin’ rhythm

and my soul keeps a-singin’ the blues.

Roll over, Beethoven

and tell Tchaikovsky the news.

So, here is Chuck Berry sitting in a restaurant reminiscing about Tommy Dorsey’s “Boogie Woogie” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood” and telling how much he adored singers like Nat Cole and Frank Sinatra.

“The Big Band Era is my era,” he says, recalling his own heroes. “People say, where did you get your style from. I did the Big Band Era on guitar. That’s the best way I could explain it.

“Let’s put it down frank. Rock had more passion to (kids in the ‘50s) because (they) were in school. I was in school when the big bands (were popular), so it had passion to me.”

The reporter wanted to make sure he was hearing Berry right. Was this rock ‘n’ roll legend saying he would have been just as happy spending his life singing ballads like Nat Cole?

“Oh, I’d have been (ecstatic),” Berry beams. “I never would have touched rock ‘n’ roll. I’m sorry. ...”

Seeing the surprise on the reporter’s face, Berry smiled sheepishly. He felt bad about breaking illusions.

“Rock ‘n’ roll accepted me and paid me, even though I loved the big bands ... I went that way because I wanted a home of my own. I had a family. I had to raise them. Let’s don’t leave out the economics. No way. ...”

Chuck Berry and Big Bands?

Chuck Berry smiling?

Act of Friendship

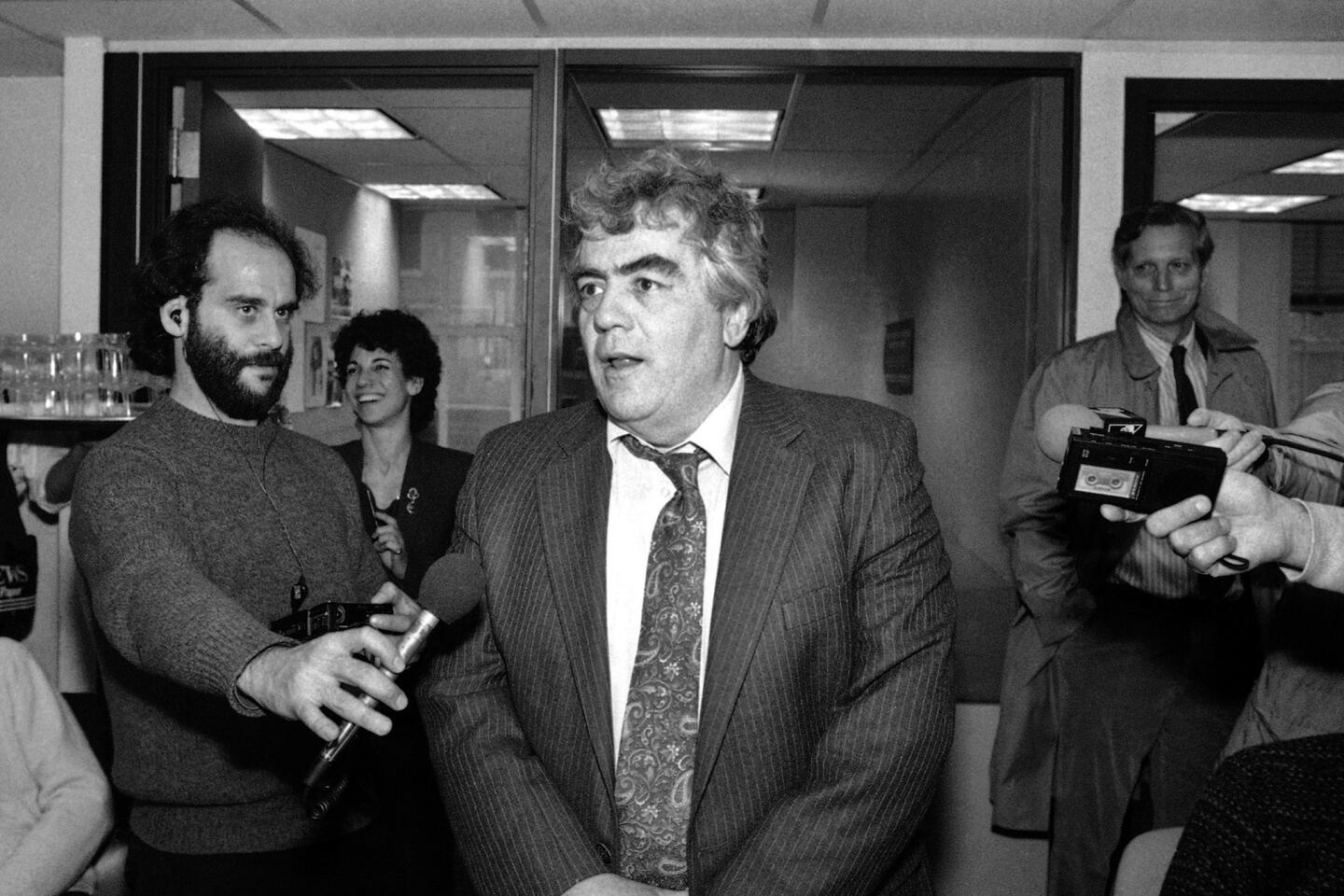

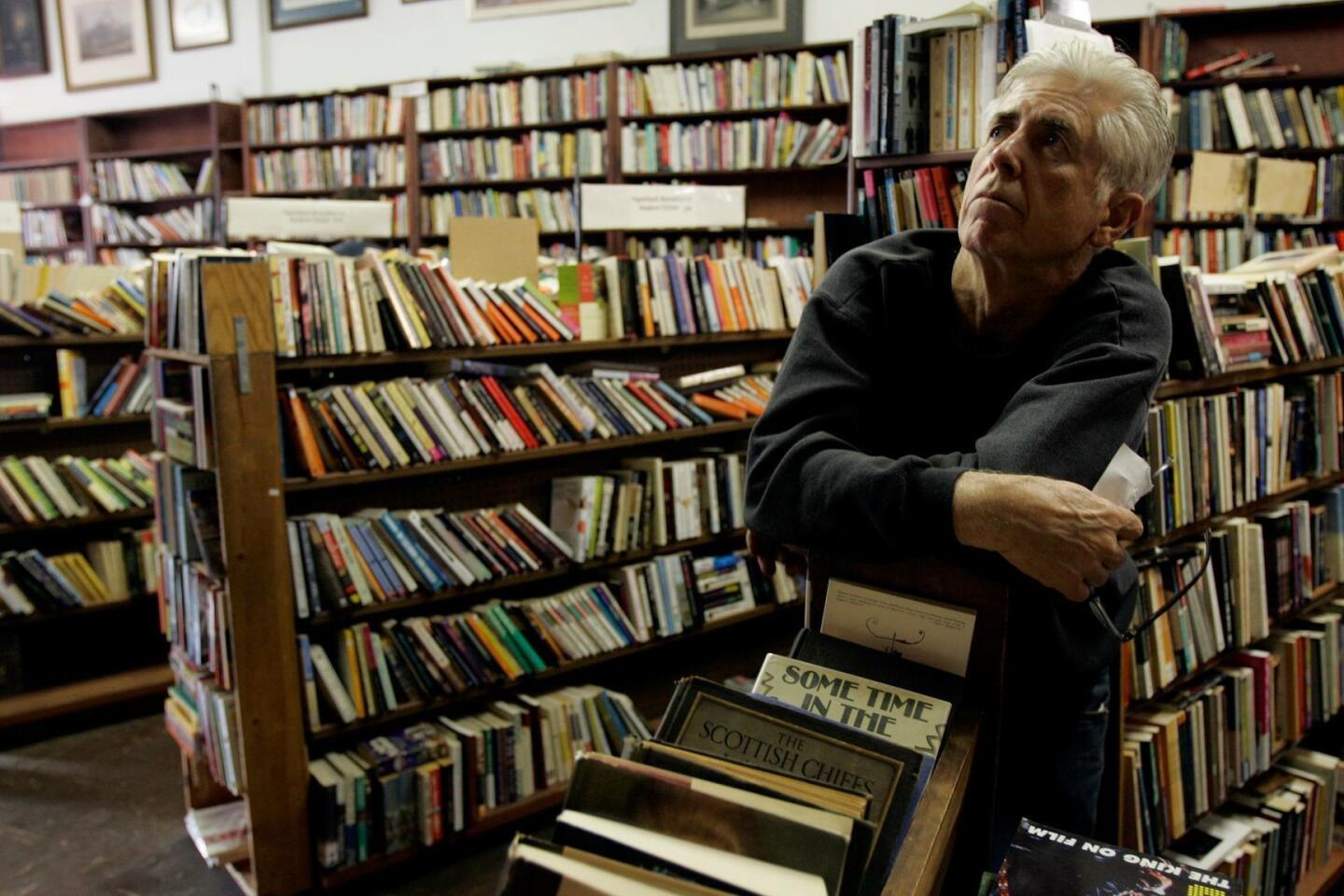

Joe Edwards doesn’t understand why many rock observers in recent years have used the word bitter to describe his friend, Chuck Berry.

“See that guitar.” Edwards points to the gold guitar in a display case near the entrance to funky Blueberry Hill restaurant. “That’s the guitar Chuck played on ‘Maybellene’ and all the early hits.

“The fact that that guitar is here tells you more about him than I ever could. It was an act of friendship that blew me away.”

The Blueberry Hill, in the rejuvenated University City district of town, has a great selection on the juke box: Patsy Cline and Lou Reed to U2 and Talking Heads. The walls of the sprawling restaurant also showcase hundreds of photos and records by ‘50s rockers – even a complete Elvis Presley room.

Edwards told Berry a couple of years ago that he was going to add some display cases and Berry casually mentioned that he might give Edwards a guitar.

“That just the way he phrased it, ‘a guitar,’ ” the restaurant owner continues. “So, I assumed it would just be some old guitar--the kind every guitar player has laying around. But when he brought out the case, I knew right away that it was the guitar. ... When he opened it, I was so (touched) that I couldn’t even speak. Think about it: A lot of rock ‘n’ roll began in that guitar.

“Now, tell me, would a bitter man give that away?”

Bitter Man?

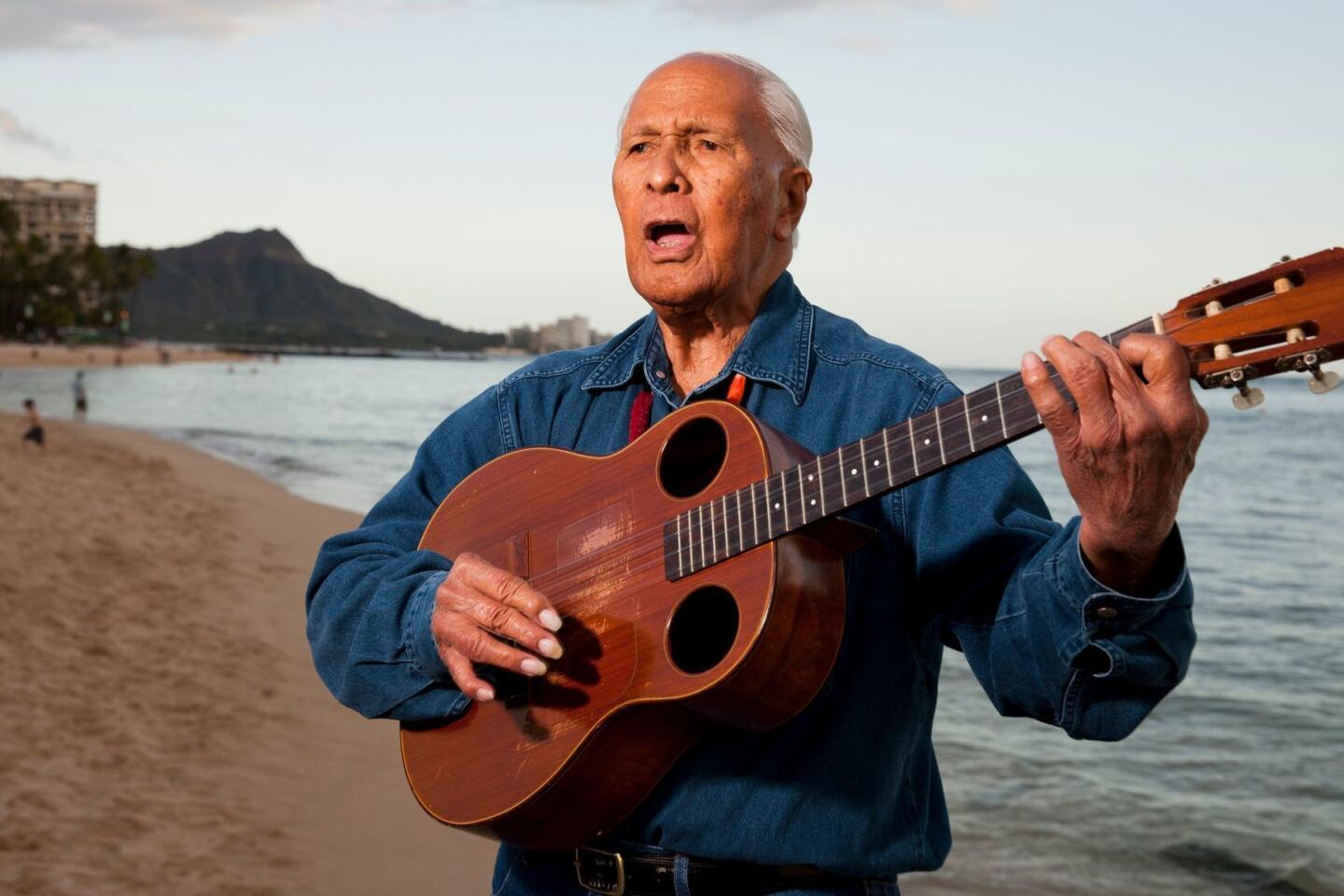

To most critics, Chuck Berry, 60, is rivaled only by Elvis Presley as the most influential figure of the first decade of rock ‘n’ roll – a man whose memorable guitar-oriented rhythm and perfectly sculptured lyrics established him in the ‘50s as the music’s first great songwriter-performer.

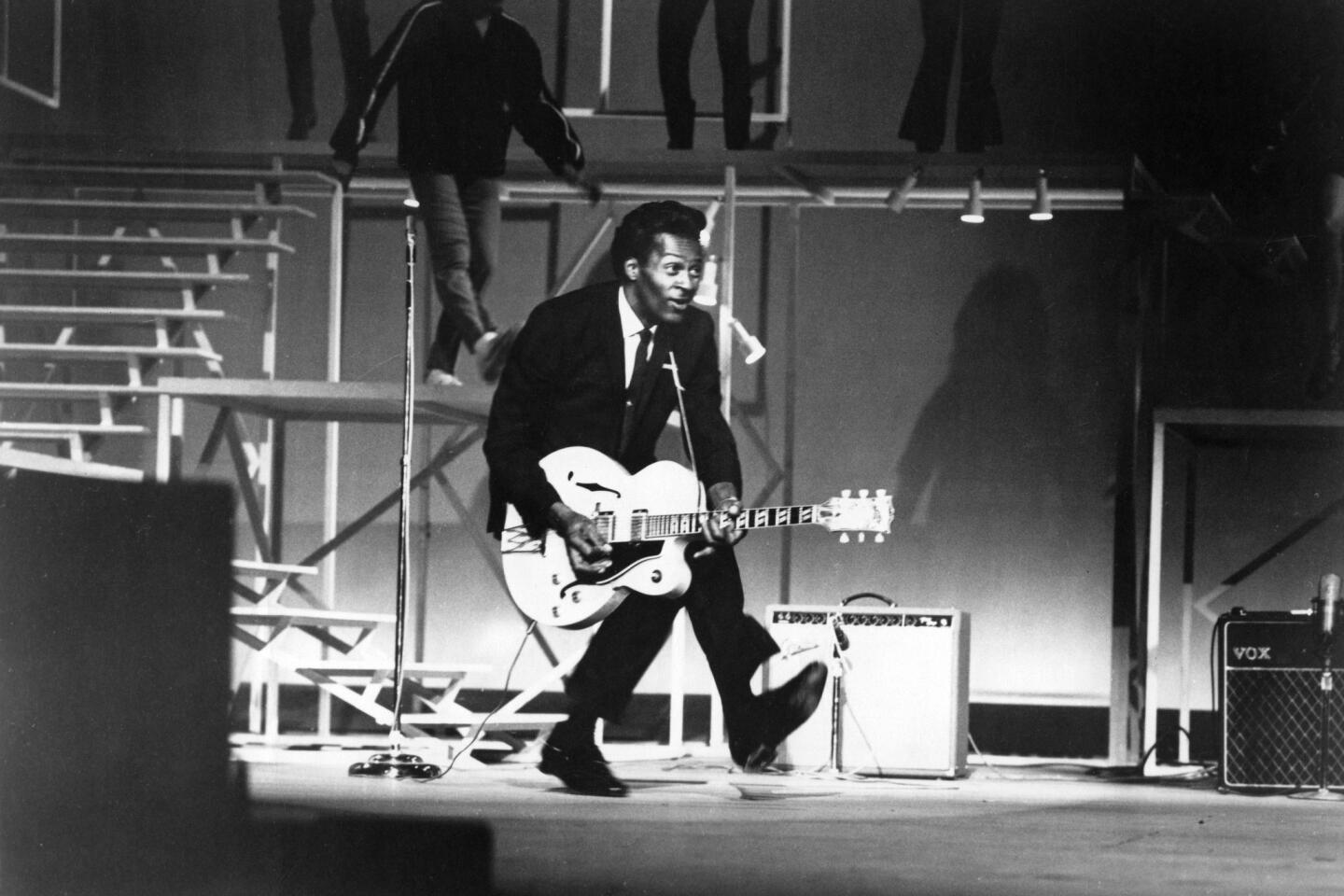

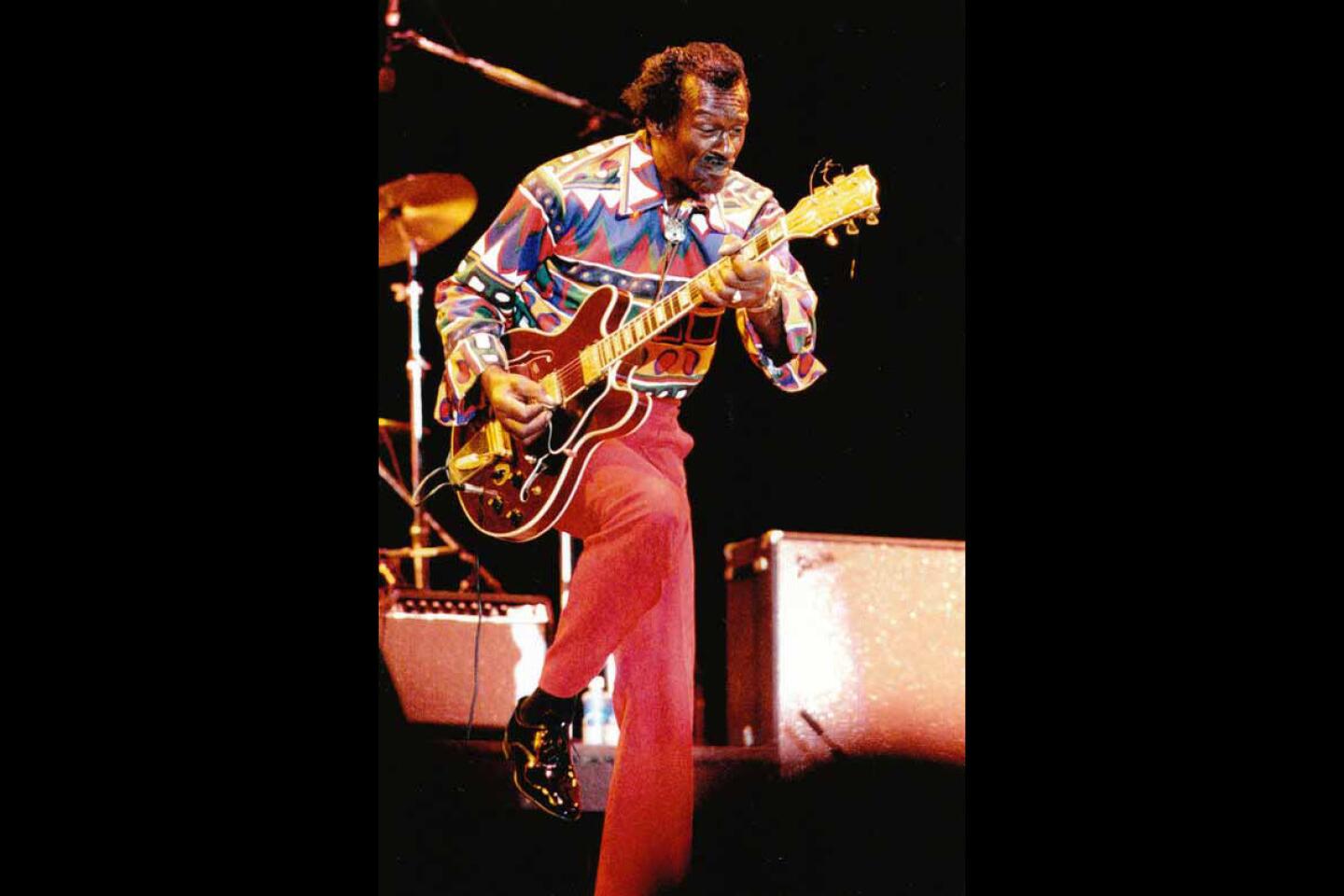

He brought his classic songs to life on stage with such an energetic show – highlighted by a zany, low-strutting duck walk – that no one in the audience seemed to notice that Berry was in his 30s, ancient by rock standards at the time, and almost a full decade older than Elvis and Buddy Holly.

If Berry’s music is widely known, his own story is not.

One reason is that Berry, for most of his career, has avoided interviews. He was angered years ago by what he feels were attempts to “sensationalize” his remarks. The only thing most fans know about him is what they have seen on stage the past two decades – and that hasn’t always worked in Berry’s favor.

Many observers have been disillusioned by Berry’s refusal to do encores, which they see as a sign that the singer no longer enjoys performing. They grumble, too, about his practice of using “pick-up” bands hired by the promoter in each city and introduced to Berry only minutes before going on stage.

Though hiring “pick-up” bands is cheaper than employing your own full-time band, it sometimes results in sloppy shows that leave fans thinking of Berry as simply a cold-hearted businessman with no respect for his music or his history.

In the absence of interviews over the last dozen years, it is easy to look at Berry’s history and build the scenario of a bitter man.

After all, Berry spent time in reform school as a teenager, served two prison terms (one for a Mann Act conviction and one for income tax evasion), no doubt saw millions of dollars slip through his hands because of the one-sided recording and publishing contracts rock performers routinely signed in the ‘50s, and experienced the sting of racial discrimination – including seeing doors open much faster for many far-less-talented white rock musicians.

But Berry’s story is finally about to be told.

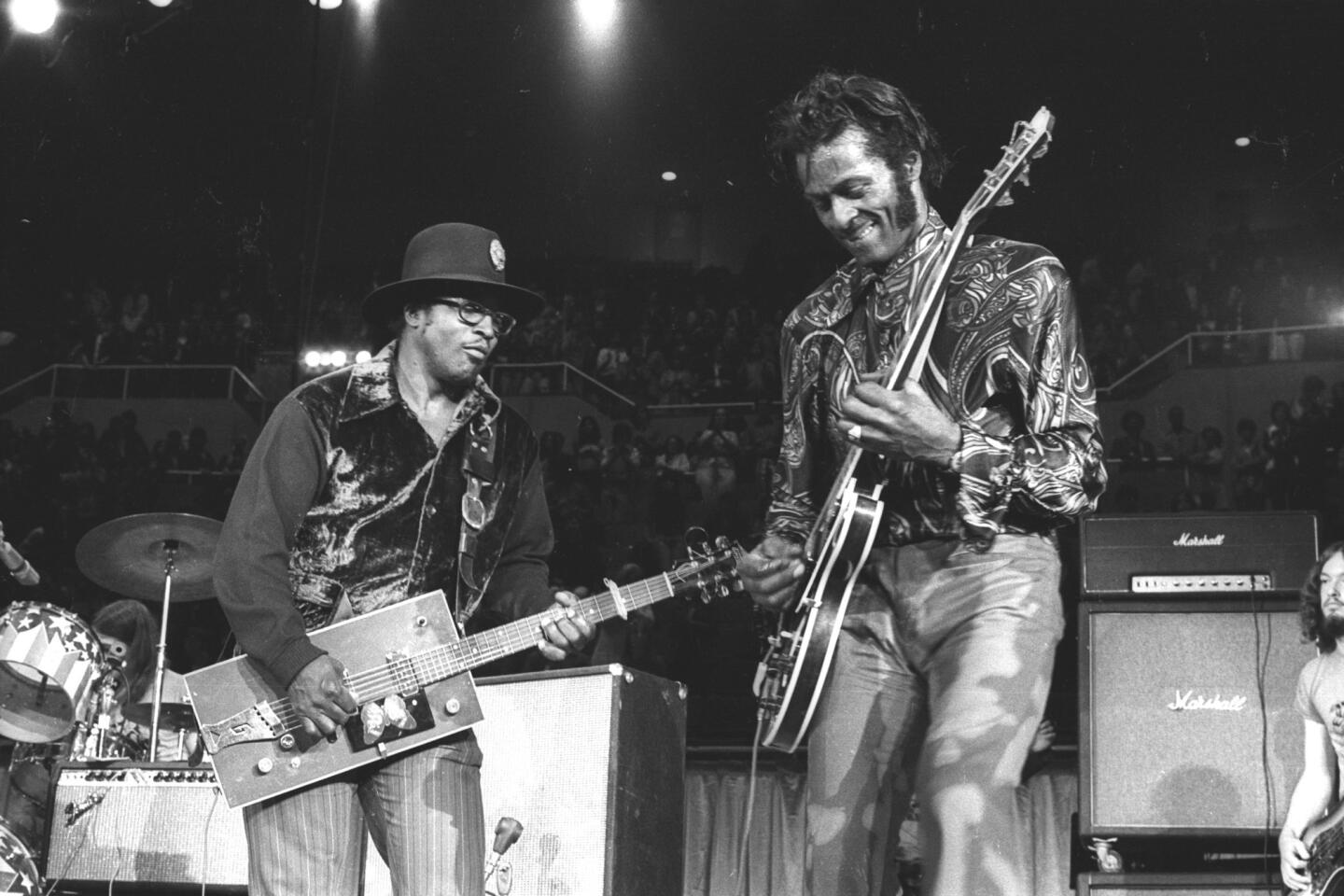

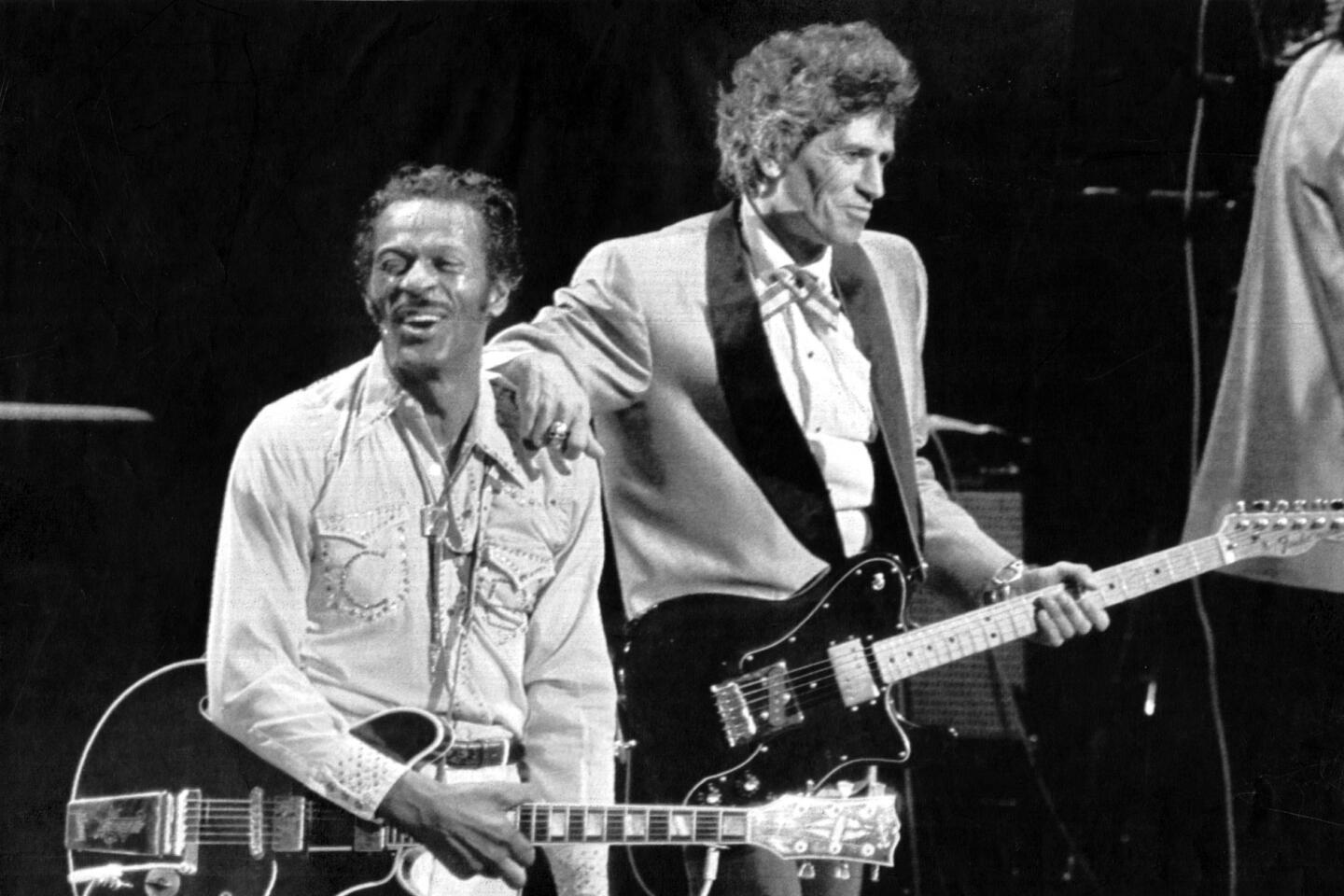

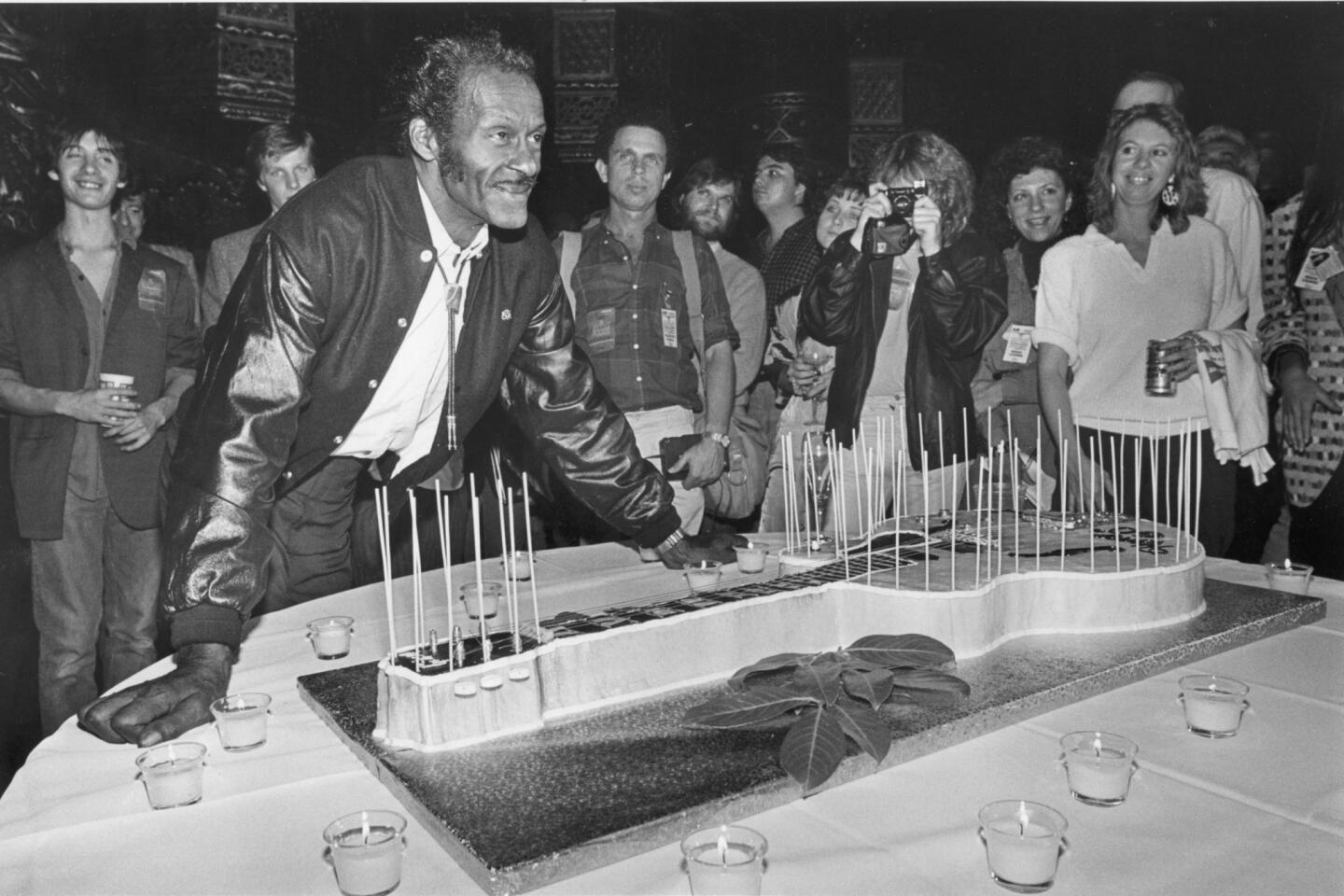

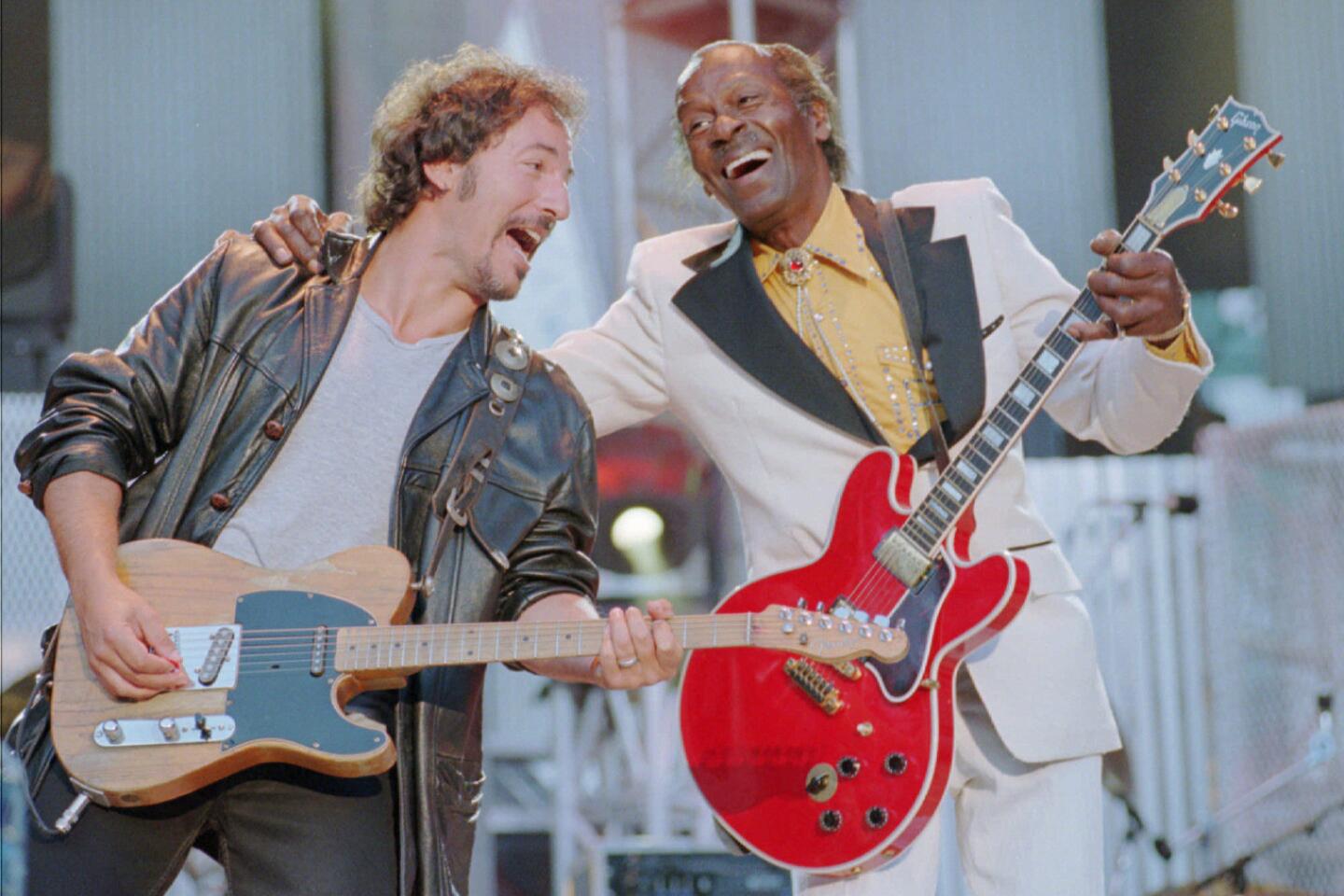

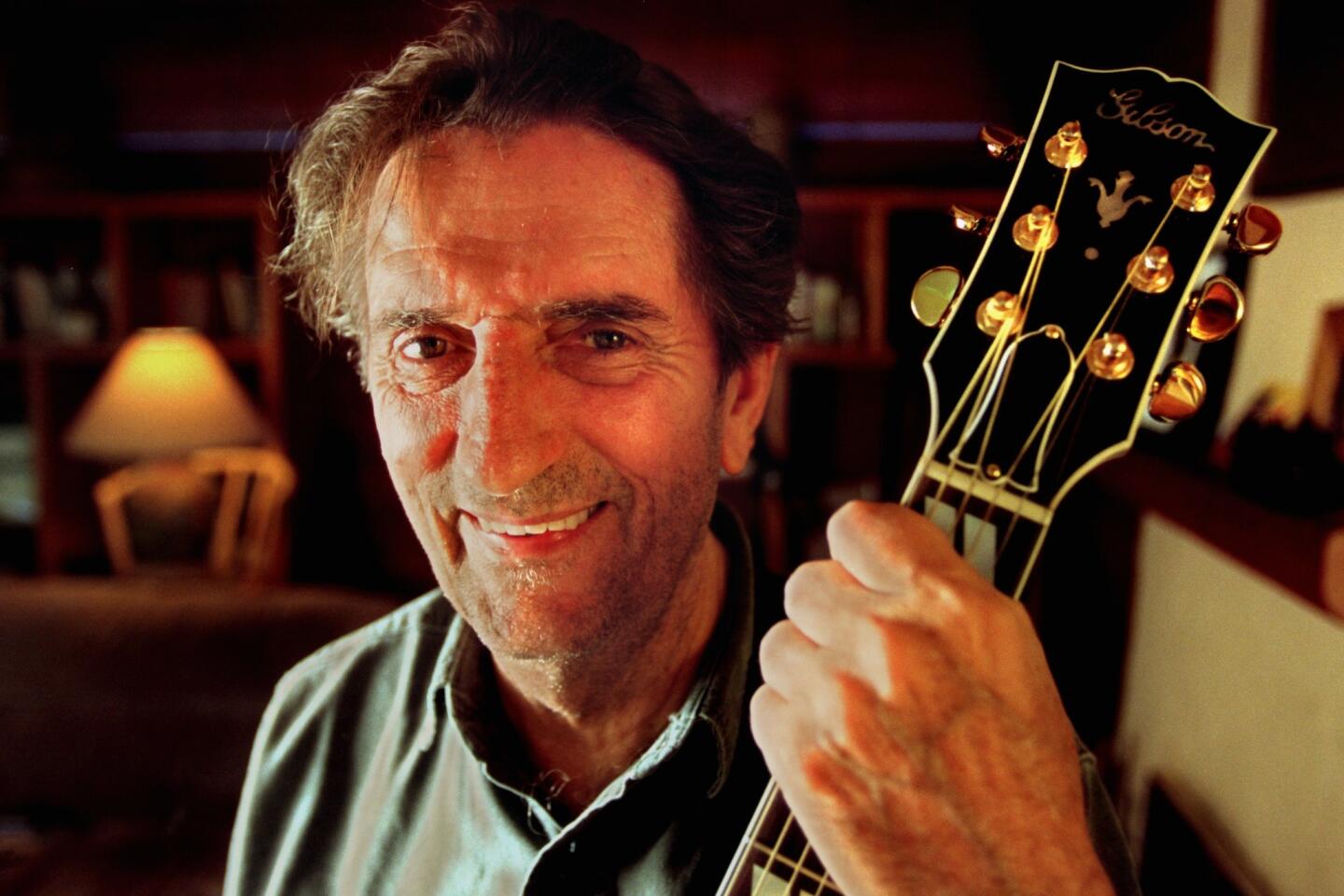

“Chuck Berry Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll,” a documentary film directed by Taylor Hackford (“An Officer and a Gentleman,” “Against All Odds”), will open Friday in Los Angeles. The film, which includes interviews with Berry, is built around a concert last October for a 60th birthday salute at the ornate Fox Theatre in St. Louis. He was joined by an all-star band featuring the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, Robert Cray and Linda Ronstadt.

In addition, Berry’s long-promised autobiography has just been released by Harmony Books. “Chuck Berry: The Autobiography” deals at length with many of the controversial moments in Berry’s life, including his 1961 conviction for violating the Mann Act (transporting a minor across state lines for immoral purposes) and a 1979 sentence in California for income tax evasion.

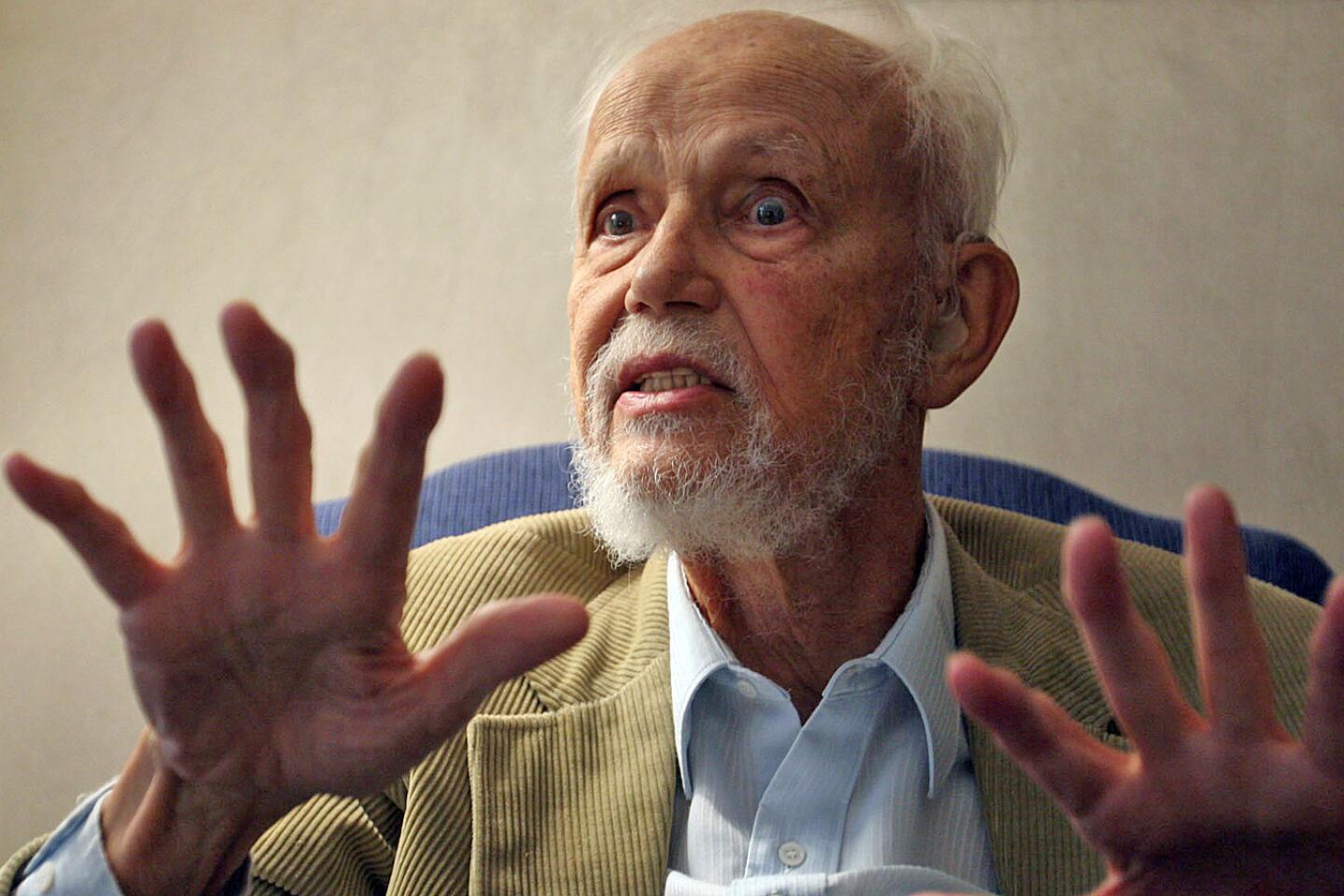

Equally important, Berry – to promote the book and film – has agreed to a few interviews.

But the early signals from a man already saddled with a “difficult” reputation weren’t good. The best that publicists for the film and the book could guarantee writers was 20 minutes.

Rejecting the Glory

Restaurant owner Edwards, 41, is so in love with rock that he owns his own Rock & Roll Beer Co., complete with a limited “heroes” series. So far, he’s only made deals with Berry and fellow rock legend Jerry Lee Lewis to have their drawings on the cans, but he’s planning to add other stars.

He explains all this while hosting the reporter from California – a job he inherited because Berry was running late. At the last minute, Berry said he wanted copies of any interview tapes.

After the first interview, he went to Edwards’ house to make a duplicate of the 45-minute conversation. Since Edwards didn’t have a high-speed machine, it took the full 45 minutes to transfer the interview to a second tape.

By the time he and Edwards returned, the schedule was off by an hour.

To avoid further delay, Edwards borrowed a second tape recorder from one of his employees so that Berry and the reporter from California could both tape the conversation at the same time. During the interview, the two tape recorders sat before them like pistols in an old-fashioned poker game.

Given his reputation, it was easy imagining Berry – a muscular man with jet-black hair who could easily pass for someone in his 40s – picking up his tape recorder if offended by a hostile question and heading out the door. The whole incident seemed like yet another piece of evidence that Berry is a guarded, cantankerous guy.

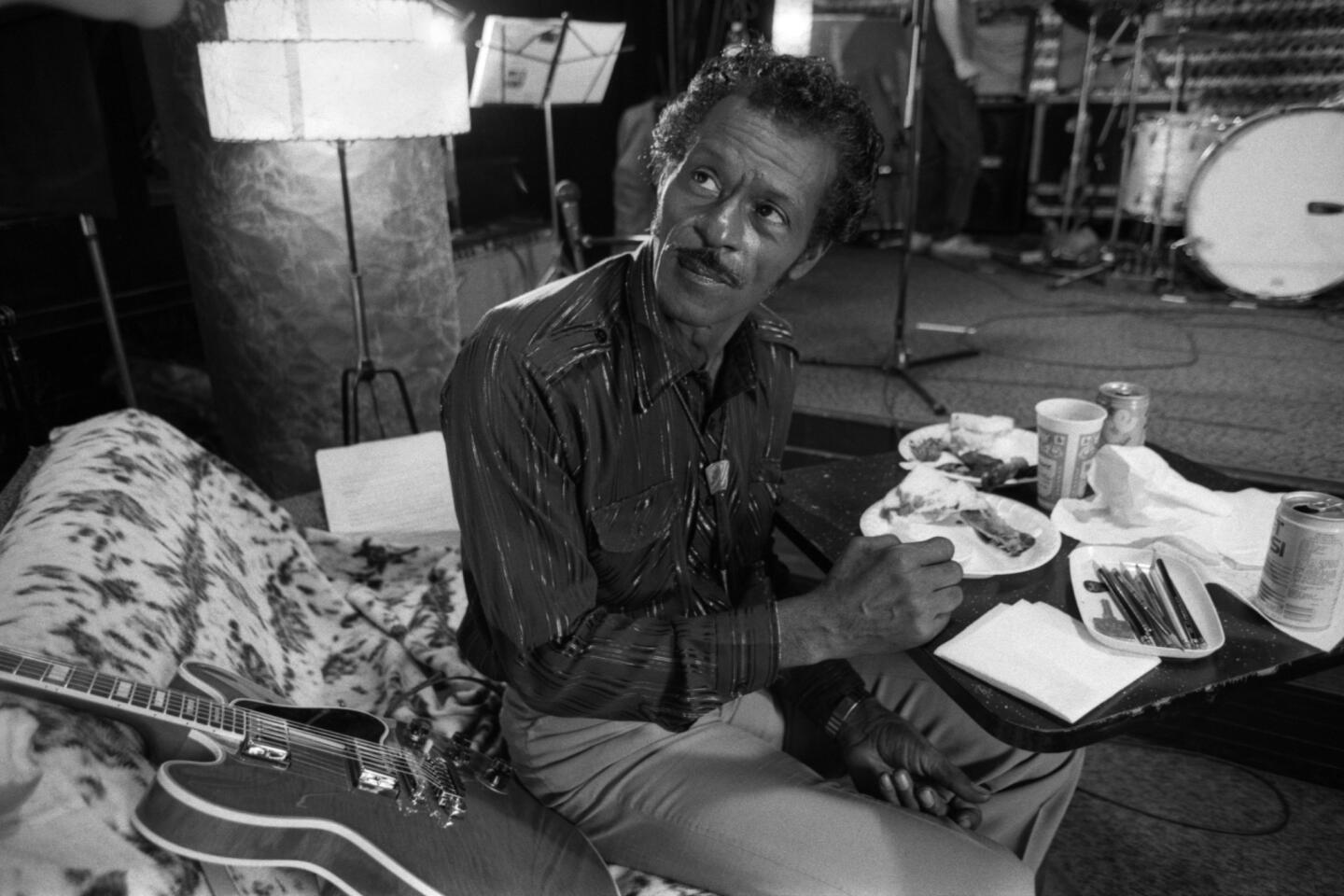

But Berry proved to be as agreeable as Edwards had predicted. When his 90-minute tape ran out, he didn’t bother stopping the interview to get another. He simply let the conversation continue.

“Forget it,” he said. “Yeah, I suppose I’d like to have the tape in case someone twists some of my words. That’s what (soured me) on doing interviews years ago. No matter what I said, they would write what they wanted to. After a while, I didn’t see any value in talking to people. But the main reason I want the tapes is that it helps me remember things (in my life), things that I might say and want to use in another book.”

Much like John Lennon, whose straight-forwardness was much admired by Berry, there is little pause or sense of self-censorship in Berry’s conversation. While surprisingly refreshing, this frankness makes it easy for him to be misunderstood.

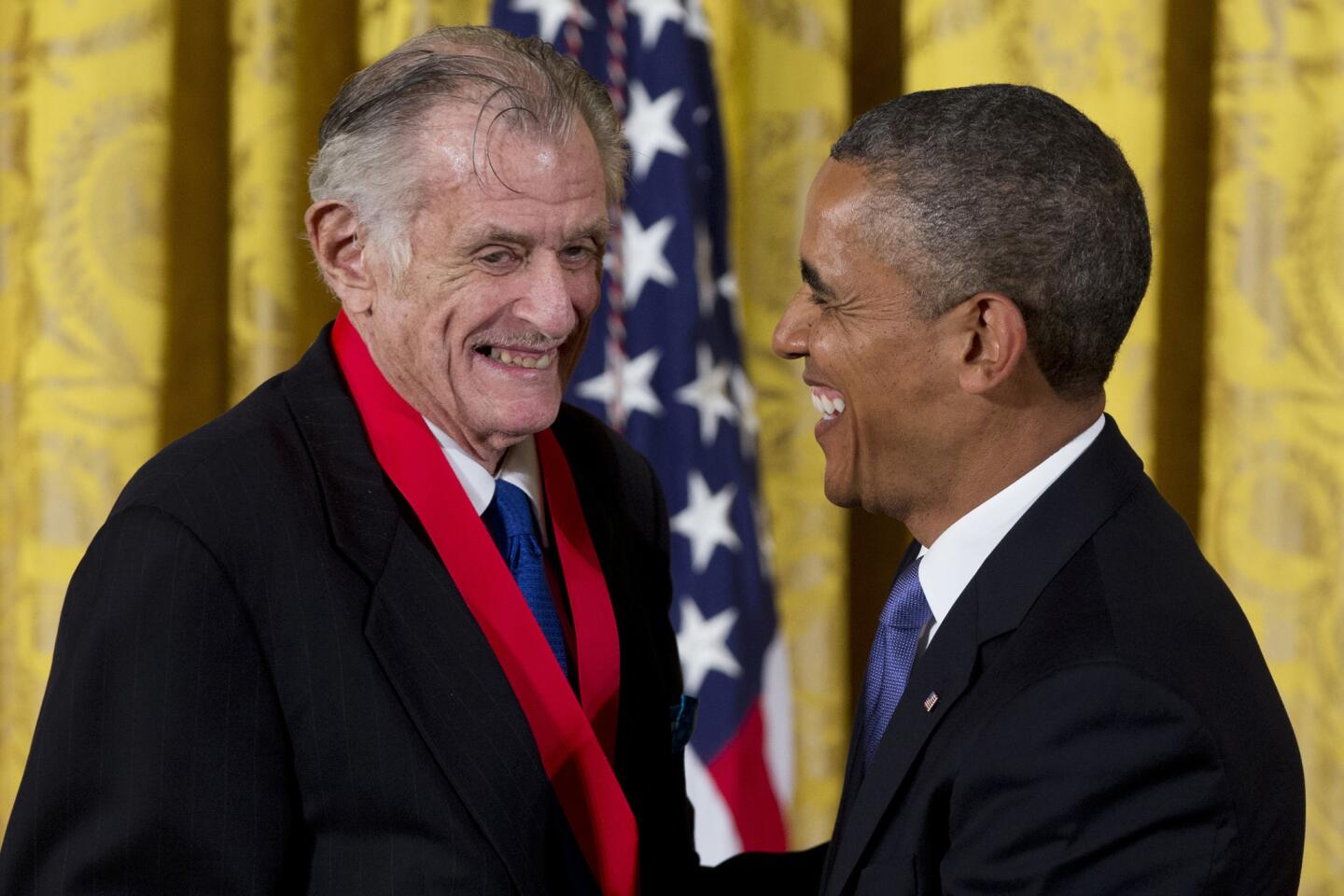

Asked how he feels about awards – specifically the 1986 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, he said, bluntly, “Those don’t mean a thing to me.”

That answer, in a 20-second TV bite, could do much to re-enforce the bitterness doctrine surrounding Berry.

But Berry, in almost Zen fashion, has worked to maintain what might be described as an “emotional neutrality” in his life.

“I don’t want the bottom, so I have to sacrifice the top...,” he says, matter of factly. “Rather than have joy, I would rather be absent of pain. … I think it is better that way because people have killed themselves over the lack of glory. They have also killed themselves from the depths of degradation.”

Art Versus the Businessman

Berry grew up in a working-class black neighborhood in St. Louis, son of a carpenter. He sang in church and began playing guitar and piano in his teens. He had eclectic musical interests and influences – from the blues of Muddy Waters and the swing of Count Basie to country and mainstream pop. He was in his late 20s by the time he joined the Johnnie Johnson trio at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis. Until then, he had worked a variety of odd jobs and had studied cosmetology. Music was more of a recreation than a career obsession – until he learned that he could make money at it.

After becoming known on the local scene, Berry signed with Chess Records in Chicago and released his first single in 1956. “Maybellene,” an upbeat novelty that appealed to the teenage rock audience, was a smash – the first of Berry’s nine Top 40 singles over the next three years.

Berry’s songs – others include “Johnny B. Goode,” “Back in the U.S.A.,” “School Day” and “Too Much Monkey Business” – are such simple, yet enduring statements that virtually every aspiring rock band since the Beatles and Rolling Stones has included at least one in its repertoire.

In trying to reflect the attitudes and aspirations of his teen audience, Berry moved beyond the novelties to touch on some of the frustrations and aspirations of young people.

“The Promised Land” is a richly appealing look at a young man’s travel across the country from Norfolk, Va., to Hollywood in search of the big time. (Berry wrote the song in prison, consulting an atlas to make sure the route outlined in the song was accurate).

Berry made more money than most ‘50s performers because he had so many hits and he was in constant demand as a live act. Besides, he gained a reputation as a hard-nosed businessman.

With his profits, he opened a club in St. Louis briefly in the early ‘60s and a more ambitious recreation park on his farm in Wentzville, 35 miles west of here. But he eventually concentrated on real estate. Among his properties: homes in St. Louis, Hollywood and several in the Wentzville area.

Now that the book and movie are coming out, Berry is not about to take it easy. He is working on a new studio album and will tour next year with his own band for the first time in years.

Berry said he stopped using a regular band years ago for two reasons: His booking agency told him it was easier to book him as a solo artist and it meant more money for him. It also meant he didn’t have to be responsible for watching over the musicians, whose drinking habits, he said, bothered him.

He dislikes encores, saying he prefers to put his “all” into the show itself. Through it all, Berry felt no need to explain himself – though he admits the back-up bands were sometimes ragged. His only obligation, he felt, was to live up to the contract. To him, it was never bitterness or indifference, only business.

Berry is co-producer (with Stephanie Bennett) of the film, but it doesn’t mean it is a glossy portrait of him. He gets in a heated exchange with Keith Richards during a rehearsal sequence, telling Richards that he is going to do it his way – not Richards’– because his way has worked for 60 years. He talks repeatedly about music in terms of the money, not art.

During the interview at the Blueberry Hill, Berry smiles when asked about art.

“(To me, art) was drawing,” he replies. “To sing was not art. In fact, I first heard the word artist (applied to music) when they said, ‘The artist go in here.’ To me, that meant the painters go in here. That was my sense of it. I grew up thinking art was pictures until I got into music and found I was an artist and didn’t paint.”

Facing the Prejudice

Big-band music wasn’t all that Berry liked in the ‘40s and ‘50s. He was also a big fan of blues singer Muddy Waters, and he listened a lot to country music. His own music would seem much closer to those styles than to big-band music. Still, the big-band singers hold a special place in his heart.

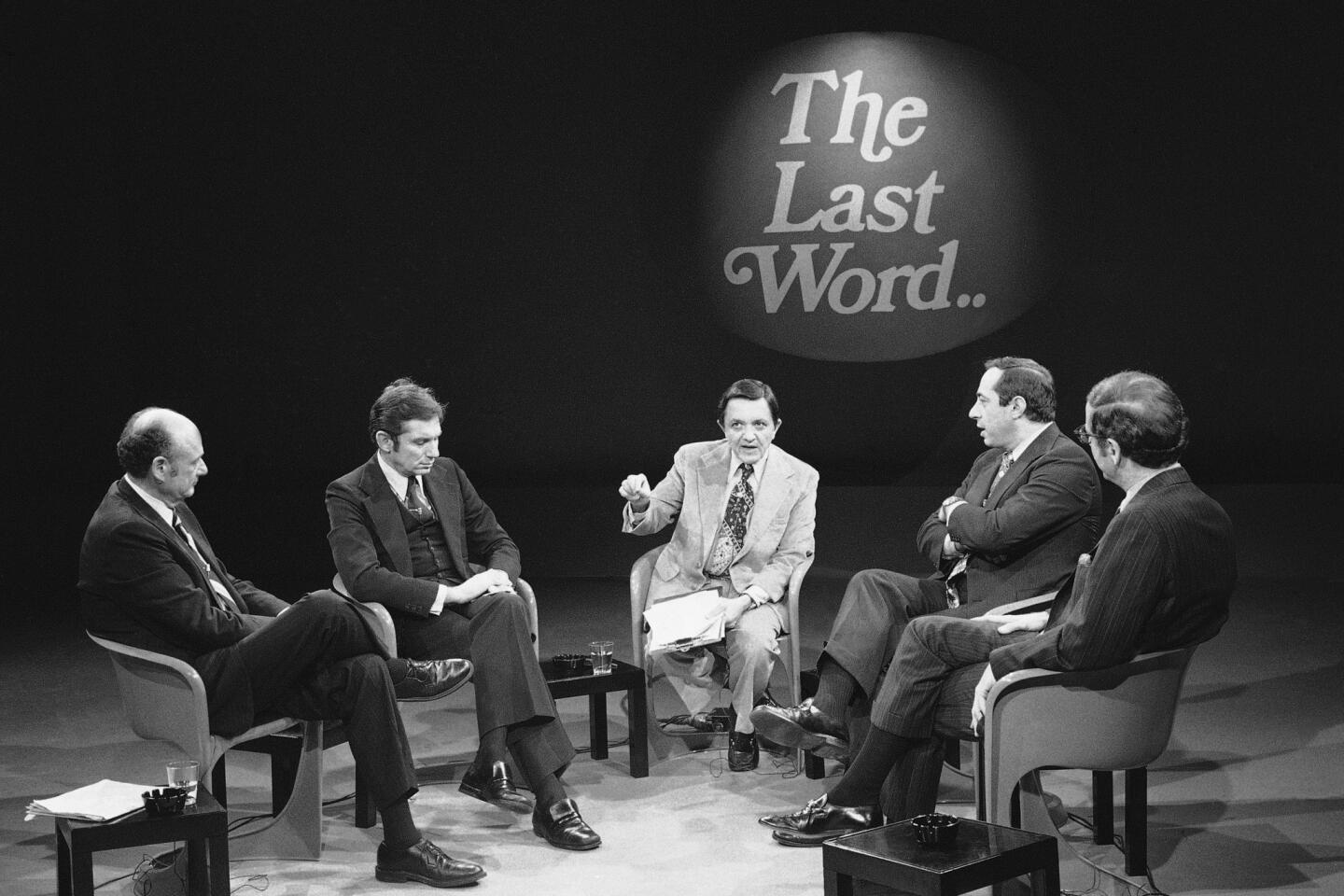

Here are excepts from the interview with Berry (some of the questions have been revised to better reflect the flow of the conversation):

Teenagers in the ‘50s saw your music as a revolt against the Big Band Era, which seemed so formal, so less spontaneous and real.

“That’s because of the lyrics. The lyrics (of the big-band songs) were not today, not right now (like rock ‘n’ roll). Everybody went to school. I directed my music to the teenagers. I was 30 years old when I did ‘Maybellene.’ My school days had long been over when I did ‘School Day,’ but I was thinking of them. (Teenagers) were the ones I was singing to, so why not sing lyrics of their life?”

Most people thought rock was just a passing fad. Did you think your career might be over quickly?

Oh yes, I can give you an example. Tim Gayle at Gayle Agency told me (after “Maybellene”): ‘You can ride on this three years.’ You play the big cities, then the middle cities, then go overseas. ... But I came up with another hit six months later, so (I figured) that this is three and a half years now. Then, I had another hit, so it was four years. I could see myself having a house by then.”

You were very frank in the book about some relationships with other women over the years. Did your wife feel uncomfortable about some of the things you wrote in the book?

“This wife of mine. I don’t even care to talk about it too much because it is not anybody’s affair, but this woman I married once and for all. My father married once. I married once. This is a conviction of ours. This is the way we grew up. Nobody can bring us apart. ...

“We lived in the basement of our first home in order to rent out the upstairs. We came up together and sacrificed. I slept in the Hertz cars when I didn’t have but four hours before catching the morning plane, going from gig to gig rather than pay $18 to Holiday Inn. This was when I was making a $100, $150, $125 a night. I’d sleep in the car and the security at the airport would tap on the window when he came to work so I wouldn’t miss my plane.”

A lot of black performers were bitter about the discrimination they experienced, especially in the South, during the early tours. You don’t seem to share that anger.

“No, I saw why (there was prejudice). Before I even went (into) music, I knew black people made bread for white people with their black hands, but to go and touch a white woman ... on the arm was forbidden, taboo. These were the things that intrigued me. Why do you eat out of my hands, but do not want me to pat you on the back? (I saw it was) a tradition ... a belief that (the whites) had.”

Elvis and you were the most important of the early rock stars, but Elvis, being white, got much more media exposure. Did you feel cheated?

“Again, I knew why. Television stations were owned by whites. ... Besides, I never saw we were rivals. ...”

But didn’t it seem unfair?

“No, it is not unfair that six people have on gray suits and I have on a blue suit or it’s not unfair that seven people are eating turkey and I chose to have chili or whatever. That’s what it was. More people chose his music than chose mine ... or my records.

“There were so many avenues that lead up to that . . . tradition, acceptance. It is more comfortable to be around your own than a foreign element. All this had to do with it (and I could see it). Now who is going to change all of that ... tradition ... just to sell a record. ...”

How about the money? Did you feel cheated the way a lot of other ‘50s artists do?

“I keep thinking about the positive side. ... I’d say, ‘Look how much money I made from writing my songs and singing them, both of which I like to do.’ ... I remember the Rolling Stones getting $50,000 in Miami on the ‘Ed Sullivan Show’ and I was making $500 a night and they were playing my song ... but (I thought) about the $500 that was coming every night. In 100 nights, I’d have $50,000.”

What’s your view of the Mann Act conviction?

“A lot of extenuating circumstances go along with it. One, I had a nightclub in St. Louis that was predominately catered to by the white populace of St Louis ... and shortly before that whites weren’t allowed into the Fox (movie theater), which was just two blocks away. Now here you’ve got what they called a mixed racial club that was catered to by whites ... and here, down the street we just are trying to see what it is like to let blacks in the Fox.

“(You could picture people saying) ‘Now this is going too fast, let’s shut the club down ... (and) in order to shut the club down, you have to (shut the owner down). That wasn’t the only thing that happened – getting me into jail from the Mann Act. Many things happened. They made us paint the walls, fix the pipes ... made us do all kinds of fire protection. But I knew why. I wasn’t wanted on Grand Avenue. I was the instigator.”

(Berry writes in the book that he met a woman in Juarez and brought her back to St. Louis to be a hostess in his club, but the woman, who told him she was 21, turned out to be a teenager.)

Let’s talk about your honors again. Isn’t it gratifying to walk into a place like this and see your pictures on the wall and your guitar in the display case, and to think how much your music has meant to people over the years?

“I swear it does not mean a thing. ... I am telling you I don’t have the good feelings or the bad feelings either. I have bad physical feelings. In other words, someone can rub my neck with a feather and that feels good. Someone kicks me on my leg, that feels bad. But if somebody says anything derogatory or someone says you are the best performer I have ever seen in my life, that doesn’t mean a thing.”

What about your music. If you had room for only three or four Chuck Berry songs on your juke box, which ones would you put?

“For rhythm and lyrics, it would be ‘Back to Memphis.’ I think it is a heck of a story ... a fellow went up north to make it and (finds) there is no place like home. It is the grown boy talking to his mother rather than little ‘Johnny B. Goode.’

“For heart-throbbing, tear-dropping, it is ‘Memphis, Tenn.,’ which is the tenderest. For novelty, it is ‘No Money Down.’ For teachings, it is ‘Downbound Train,’ because it is spiritual and it shows if you really need to do well, you will do well.”

What are the rewards now? Just money?

”... I wouldn’t be out there (anymore) if it was money only. ... My money is making enough money for me to live on (for the last) five to eight years ... not only me but all my people. The money is never (ignored). I wouldn’t work benefit after benefit the rest of my life. But it isn’t the main reason I go out anymore.”

What do you think about the film? The ending, where you are alone at the piano singing “Cottage for Sale,” is quite touching.

“I am hoping (the film) makes it into the hearts of many people, which will mean box office ... but if I had directed that film I would have had a flair of an ending instead of the quiet ending. I would have ended it like my show. I would never stop my show with ‘Cottage for Sale’ or anything like it. I want to leave sweating, hot and happy and hearing (the applause).”

ALSO

Exclusive: Stevie Wonder to give keynote address at 2017 ASCAP Expo

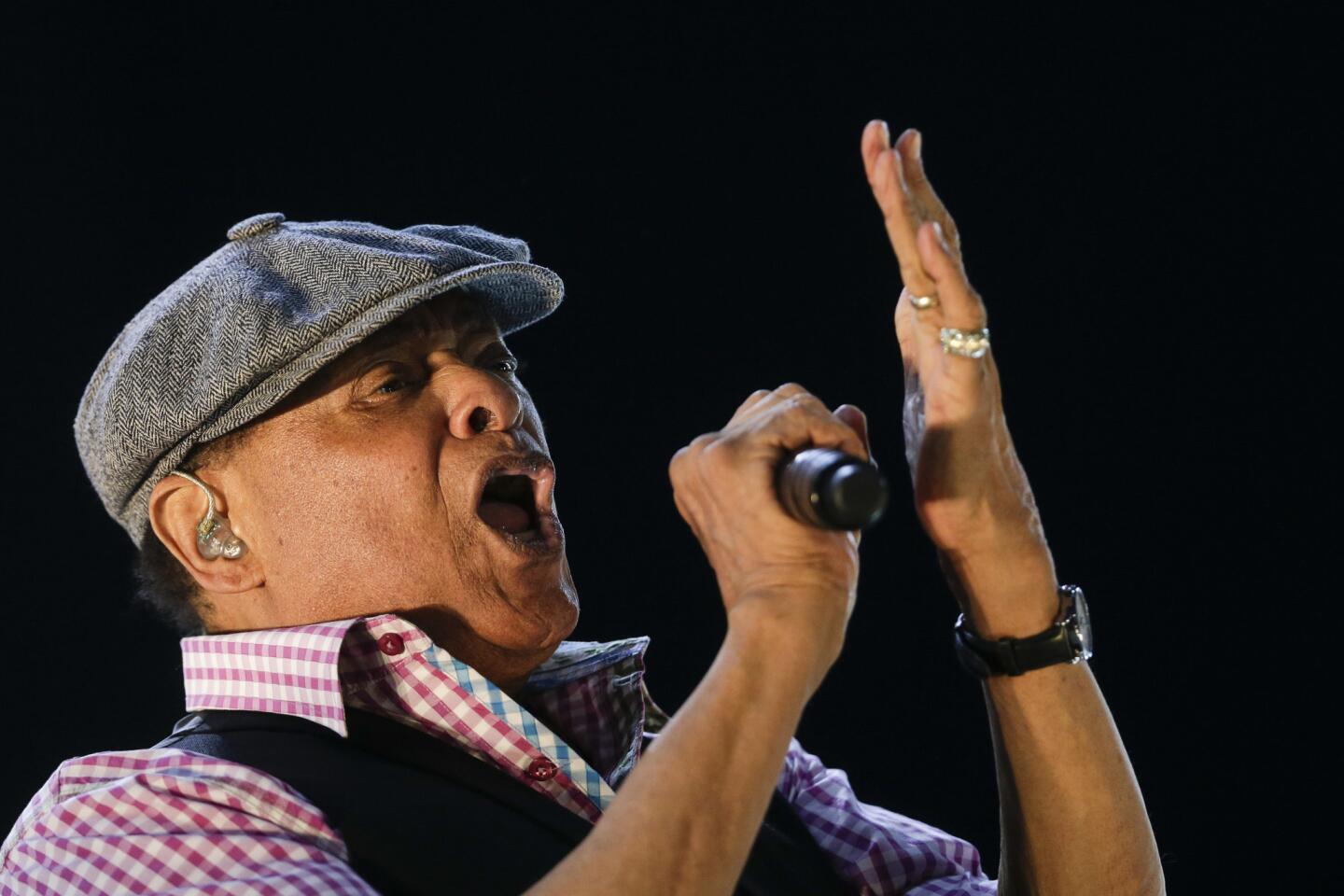

Blues harmonica player James Cotton, Mr. Superharp, dies at 81

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.