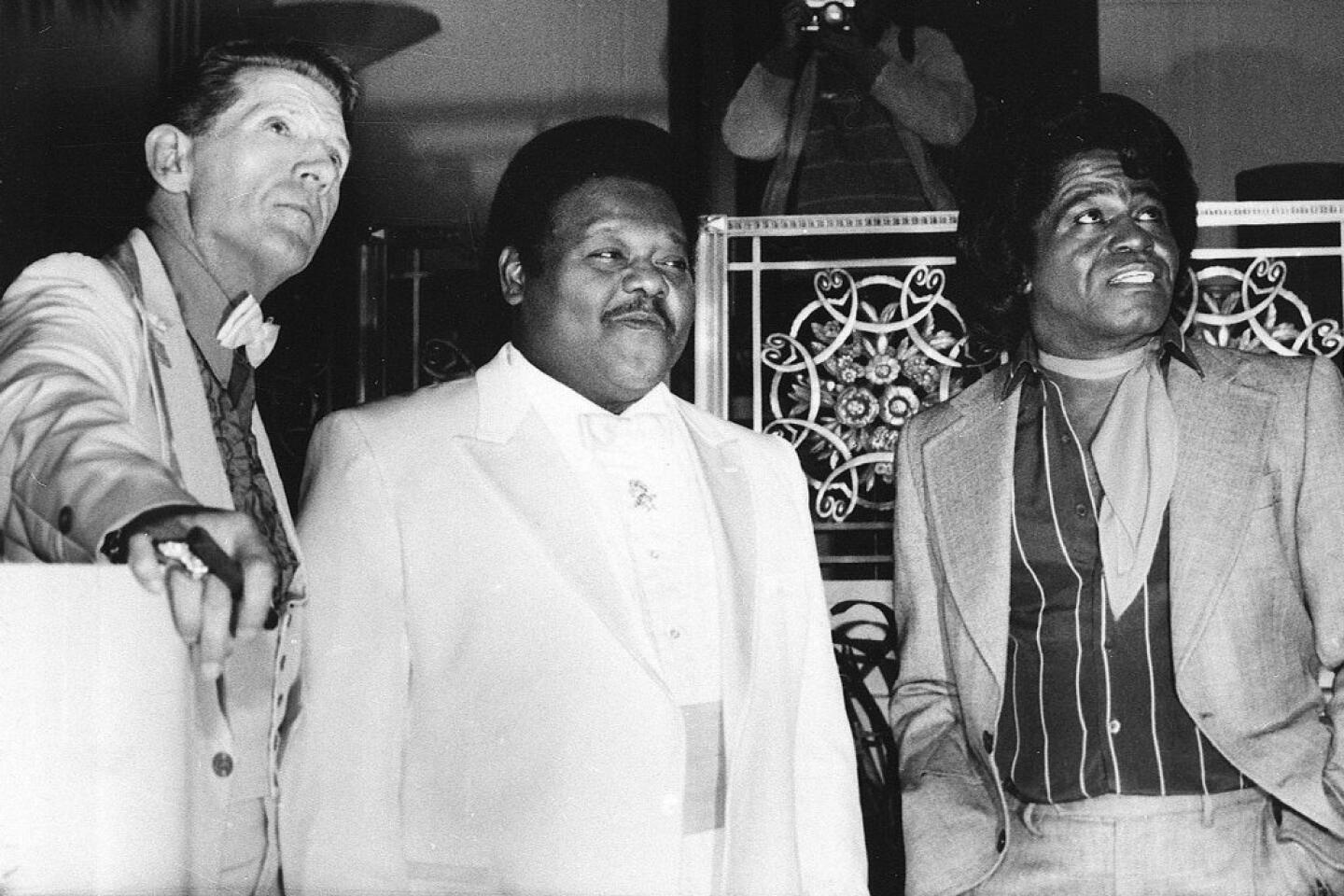

Fats Domino, rock ‘n’ roll pioneer and New Orleans hero, dies at 89

- Share via

As one of the founding fathers of rock ’n’ roll, Fats Domino blazed a singular path in the history of popular music. Pounding a piano and booming in a baritone both warm and conversational, he gave the nascent genre a shot of rhythm and blues, jazz and boogie woogie from his native New Orleans.

Fueled by archetypal 1950s hits such as “Blueberry Hill,” “Ain’t That a Shame,” “I’m Walkin’ ” and his version of “My Blue Heaven,” he was also credited as proving that the piano had as vital a place in rock ’n’ roll as the guitar.

Domino died early Tuesday at 89, leaving Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis as the last surviving architects of rock after Chuck Berry died in March.

Citing the coroner’s office in Jefferson Parish, La., the Associated Press reported Wednesday that Domino died of natural causes. On Domino’s Facebook page, his children said their father had died peacefully at home and thanked fans for “the outpouring of love and tribute.”

In the ’50s, Domino was one of the biggest stars in pop music, selling more records in that decade than anyone except Elvis Presley. Thirty-seven of his singles made the Top 40 — more than Little Richard, Lewis and Berry combined— with 11 of them reaching the Top 10.

“He’s the greatest entertainer that I ever [knew],” Little Richard told Billboard Tuesday. “Black, white, red, brown or yellow, he’s a just good guy and I thank God for giving me the opportunity to know him.”

Domino was one of the cornerstones of rock ’n’ roll, helping define the form with such R&B-rooted early-’50s records as “The Fat Man,” “Goin’ Home” and “Please Don’t Leave Me.”

The singer and pianist followed his 1955 national breakthrough, “Ain’t That a Shame,” with a barrage of mainstream hits, including “Blueberry Hill,” “Walking to New Orleans,” “Blue Monday” and “I’m Walkin’.”

Working with his indispensable collaborator Dave Bartholomew, Domino showed an uncanny knack for taking songs from diverse genres — country, Tin Pan Alley standards, folk songs — and turning them into unmistakable Fats Domino records.

He rarely strayed from the basics of New Orleans-style R&B, and his adherence to his hometown’s unique mash-up of blues, country, Dixieland and zydeco made Domino a beloved figure in the city.

But his impact was international. He was adored by British youth, and the opportunity to meet Domino was a treasured perk for the Beatles. “Ain’t That a Shame” was the first song John Lennon learned, and Paul McCartney paid homage with the Beatles’ Domino-style record “Lady Madonna,” which Domino himself eventually covered.

He was an acknowledged hero to Elton John, and when Billy Joel inducted Domino into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 as one of its first 10 inductees, he called him “the man that proved that the piano was a rock ’n’ roll instrument.”

Unlike Lewis, Little Richard and Berry, Domino was no cultural renegade. Humble and soft-spoken, he projected a docile, amiable image, smiling cherubically and flashing his bulky diamond rings as he played.

His ambitions were modest, his life unassuming. Despite his hectic schedule of touring and recording, he remained rooted in his childhood neighborhood, where he enjoyed cooking Louisiana dishes, cracking a bottle of beer and spending time with his family. He married Rose Mary Hall in 1948 and they had eight children with their father’s initial in common: Antoinette, Antoine III, Andrea, Anatole, Anola, Adonica, Antonio and Andre.

“I was lucky enough to write songs that carry a good beat and tell a real story that people could feel was their story too,” Domino told The Times in 1985. “Something that old people or the kids could both enjoy.”

Antoine Domino Jr. was born Feb. 26, 1928, the youngest of nine children. It was a poor family, and a musical one, and Antoine learned piano from a brother-in-law, Dixieland musician Harrison Verret.

The youngster was performing in public by age 10, and at 14 he quit school to work at a variety of jobs. One of them, at a bedspring factory, nearly ended his career before it started when he cut his hand so badly that the doctor who examined him advised amputation.

Domino declined, and at 18 he was a member of Billy Diamond’s band playing the Hideaway club. He emulated such pianists as barrelhouse master Meade Lux Lewis, jazz great Count Basie and New Orleans’ own Professor Longhair, and he embraced the new sounds of rhythm and blues, led by Louis Jordan, Roy Milton, Big Joe Turner and other singers. Before long, Domino was leading his own band and drawing crowds to the Hideaway.

One fateful night in 1949, Bartholomew dropped in to size up the young singer. The popular New Orleans trumpeter and bandleader had signed with Los Angeles-based Imperial Records, whose owner, Lew Chudd, commissioned him to sign artists to the label.

“When I went down there, people were standing in line, trying to see him,” Bartholomew told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 2010. “It was rough trying to get in there. It looked like the whole of New Orleans had turned out to see him.

“Fats was breaking up the place, man.” he added. “He was singing and playing the piano and carrying on. Everyone was having a good time. When you saw Fats Domino, it was: ‘Let’s have a party!’ ”

In December 1949, Bartholomew took Domino to the J&M recording studio, and one of the eight songs they cut that day, “The Fat Man,” reached No. 2 on the R&B chart in 1950.

Imperial kept the Domino releases coming. Several did well in the R&B market, and a few even sneaked onto the pop chart. Then came 1955 and “Ain’t That a Shame” (mistakenly titled “Ain’t It a Shame” on the original release), which hit the promised land of the pop Top 10.

He would return there repeatedly over the next five years, with “Blue Monday,” “All by Myself,” “Blueberry Hill” (the Los Angeles recording was one of his few songs cut outside of New Orleans), “Whole Lotta Lovin’ ” and more, most written by Domino and Bartholomew. In addition to his own hits, he got exposure — and royalties — through versions of his songs by Pat Boone, Teresa Brewer and Rick Nelson.

Those antiseptic hits were no match for Domino’s records, which captured the exuberant R&B spirit that undergirded the new phenomenon of rock ’n’ roll. Bartholomew’s perfectionist production and arrangements were essential, as was the all-stops-out playing by such great musicians as saxophonists Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty and drummer Earl Palmer — not to mention the star’s own dynamic keyboard work and distinctively slurred voice.

The British Invasion and subsequent upheavals in pop music sidelined Domino, and most of his peers, in the ’60s, but he kept at it, signing with ABC Paramount and other labels, performing at rock ’n’ roll revival shows and later becoming a fixture in Las Vegas showrooms, where he developed and then conquered a serious gambling problem.

Domino received a lifetime achievement Grammy in 1987, but his shyness and growing performance anxiety made him increasingly reclusive. He did his last tour in 1996 and then was in and out of the public eye.

In 2005, however, Domino experienced a renaissance with renewed interest in his legacy. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Domino was initially reported missing — and feared dead.

In fact, Domino was safe after being rescued by boat from the rising waters at his house in the Lower Ninth Ward. His reappearance was welcomed by a city whose music community had been hit hard by the storm, but Domino himself didn’t relish this return to the spotlight. He had rigorously maintained a low-key life for decades.

He released an album called “Alive and Kickin’ ” in 2006 and appeared on “Goin’ Home,” a 2007 tribute record that featured McCartney and others, but he played only a few shows after 2000. He declined an invitation to accept his National Medal of the Arts at the White House in 1998.

Domino, who remained a resident of the Ninth Ward neighborhood where he grew up until Katrina forced him to move to nearby Harvey, summarized his career in a 2007 interview with USA Today.

“I’m glad that people liked me and my music,” he said. “I guess it was an interesting life. I didn’t pay much attention, and I never thought I’d be here this long.”

Richard Cromelin is a former Times staff writer. James Reed is The Times’ entertainment news editor.

ALSO

Listen to 10 Fats Domino songs that shook the world

New Orleans legend Fats Domino is remembered by those he influenced

UPDATES:

2:25 p.m.: Story added a quote from Little Richard.

9:15 a.m.: This story was updated with additional information about Domino’s career and legacy.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.