Photographer Laura Aguilar, chronicler of the body and Chicano identity, dies at 58

- Share via

Laura Aguilar’s interest in photography began not in a museum, not in school and not while turning the pages of some hallowed book. Instead, she came to the medium as the result of mundane sibling rivalry.

She was in junior high; her older brother, John Lee Aguilar, was in high school. One day he showed up at their home in San Gabriel with a fancy new camera.

“It had all these lenses — the telephoto, right angle, micro and macro, and I wanted to touch them,” she recalled in a 2014 oral history for the Chicano Studies Research Center at UCLA. “He went, ‘No!’ And I go: ‘I want to do photography. I want to take pictures.’”

Unlike her late brother, who eventually moved on to other interests, Aguilar kept her passion for photography. In fact, it is for the manner in which she deployed the camera that she will best be remembered.

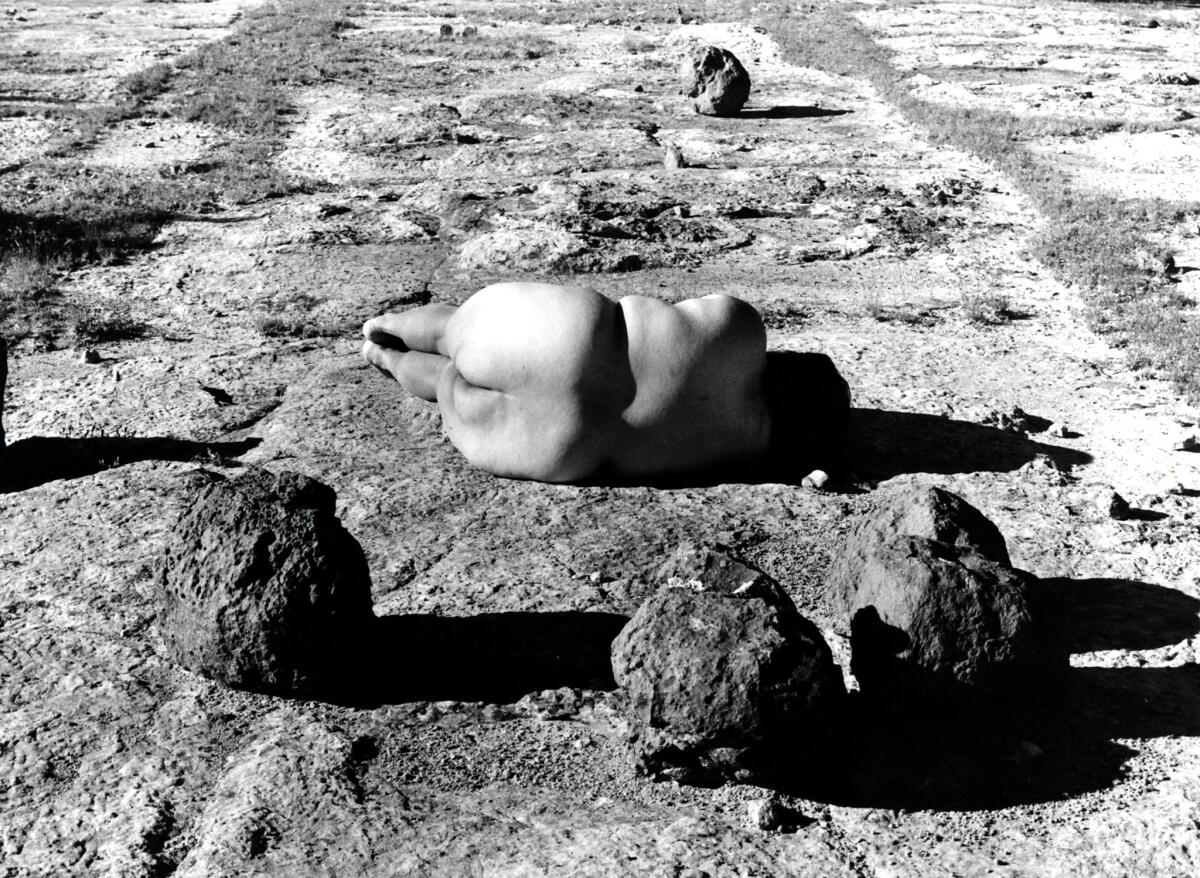

The Los Angeles photographer, known for chronicling the denizens of a working-class Eastside lesbian bar in the 1990s and for utilizing her nude body like sculpture in desert landscapes, died early Wednesday at a nursing home in Long Beach. She was 58.

“She died in peace having spent her last day with many loving visitors,” said Sybil Venegas, an independent curator and friend who helped manage the artist’s affairs toward the end of her life. Aguilar had long contended with diabetes and was suffering from end-stage renal failure at the time of her death.

“Laura’s passing is a profound loss,” said Chon Noriega, director of the Chicano Studies Research Center. “She had an ability to cut through the biases and habits of thought that makes us see a smaller world than actually exists. And she did it as an expression of the stunning beauty of the human body, including her own.”

She was both the subject and the object. She was both the photographer and the mood.

— Susanne Vielmetter, gallerist

Aguilar had recently been the subject of the retrospective “Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell” at the Vincent Price Art Museum on the campus of East Los Angeles College, and her photography appeared last year in the two-part exhibition “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” The shows, part of the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA series of exhibitions, helped resuscitate her profile at a time when her health had been in decline.

In her review of “Show and Tell” for this paper, Leah Ollman described the exhibit as “one of the revelations brought forth by Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA.”

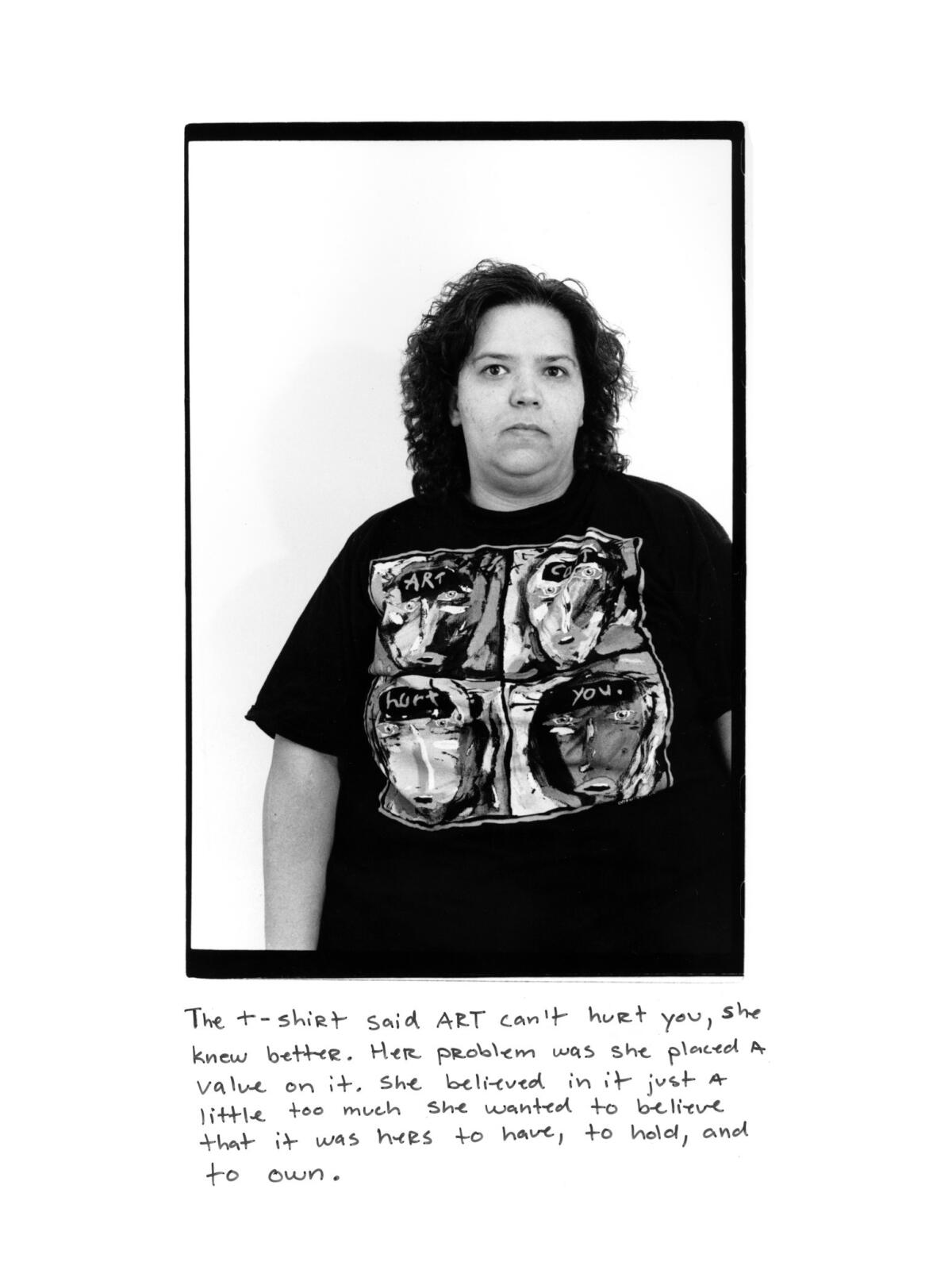

Aguilar, Ollman wrote, took the medium of photography — which had democratized portraiture — and pushed it forward “by turning her lens toward photographically under-represented subjects like herself: Latina, lesbian, large-bodied.”

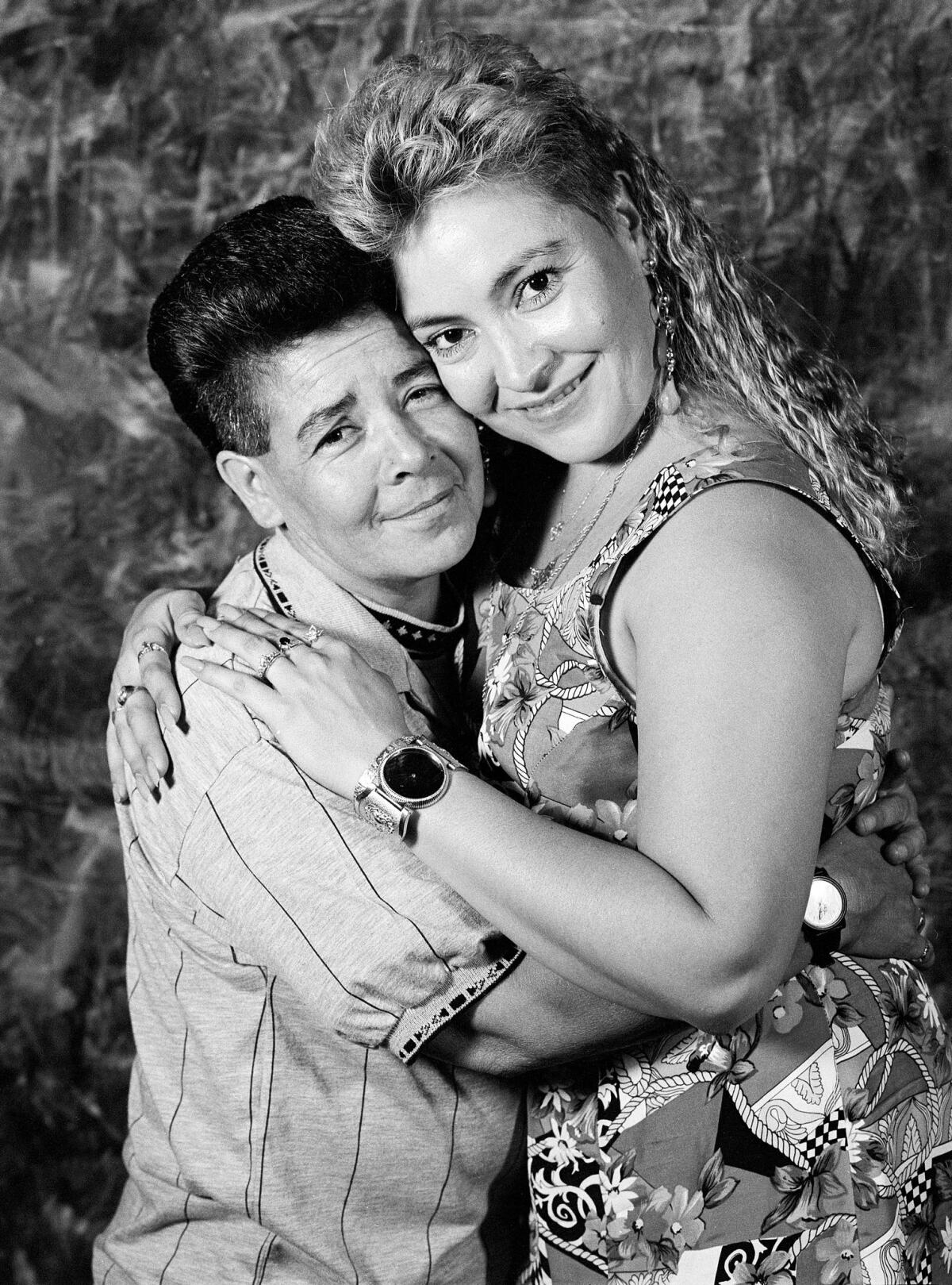

The exhibition chronicled the artist’s beginnings in the late 1980s, when she created portraits of East Los Angeles artists in Day of the Dead costumes. She photographed high-profile Latina lesbians as a way of countering the whiteness of the mainstream gay-rights movement, and later hauled her camera to a lesbian haunt in El Sereno so she could capture a slice of Latina lesbian working-class life.

“Show and Tell” also captured the moment, in the 1990s, when her work took a turn toward the visceral and the conceptual. In the 1990 triptych “Three Eagles Flying,” she renders herself nude, bound in rope and surrounded by the Mexican and U.S. flags — a woman held prisoner by the conventions and ideologies of the two cultures from which she hails.

Her big breakthrough came later that same decade when she created a series of poetic nude photographs that drew widespread critical attention. Inspired by the work of photographer Judy Dater, known for nude self-portraits in nature, Aguilar set out to do her own versions in expansive Southwestern landscapes — draping herself on rocks, curling herself into fetal positions and otherwise inserting her naked body into the landscape in ways both wry and alluring. She’d arrange her body and those of other women like ethereal props.

“She is at once part of the American land, and the viewer’s eye, and apart from them,” Michelle Hart wrote of these images in the New Yorker late last year, “in her own words, both present and persistently unseen.”

On the occasion of a solo exhibition of these works at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects in 2003, an LA Weekly writer said: “She is apparently free from common objectification. She is free to make an object of herself.”

Ironically, her work was perhaps most seen — and understood — only at the end of her life.

Venegas, who curated the “Show and Tell” retrospective, and who mentored Aguilar as a student in the 1980s at East Los Angeles College, said Aguilar was an artist ahead of her time.

“Everyone talks about gender and identity and body politics now,” she said. “But in 1990, she was way out there. When she started doing the lesbian portraits, there were a lot of people in the [Latino] community, they were not ready to go there. Those ideas were not really embraced by Chicano/Latino artists at the time. It was a very different world than today.”

Susanne Vielmetter, who organized several Aguilar exhibitions at her gallery in the early 2000s, said the artist was prescient about so many topics relevant to image-making today.

“At the time she was doing it, I didn’t really have a language for it,” Vielmetter said. “But I thought what she was doing was decades ahead of its time, especially if you look at race, if you look at the history of landscape photography, if you look at the male gaze, if you look at the body and its relationship to nature and its particular connection to the American West.

“It was all about photography and the gaze. She was both the subject and the object. She was both the photographer and the mood.”

Aguilar was born in San Gabriel, on Oct. 26, 1959, the daughter of Paul Aguilar, a welder by trade, and Juanita Grisham, a housekeeper — both of whom were of Mexican descent.

She was a fifth-generation Angelena who could trace her roots to the middle of the 19th century and has ancestors buried at the San Gabriel Mission. As an adult, she settled in Rosemead — not far from where she was born — in a clapboard bungalow built by her great-grandfather. She remained there until this year, when her deteriorating health required a move to a nursing home.

Aguilar’s home life, by her own account, was tumultuous. Her parents had a turbulent marriage and were unaware of her health problems: She had not only bouts of depression but also a severe case of auditory dyslexia, which made it difficult for her to read and communicate verbally.

At one point, her mother suggested she drop out of high school because she didn’t seem to be able to learn to read.

“In school ... people thought she couldn’t speak English,” Venegas said. “People thought she was incapacitated or mentally slow. But that was not the case.”

Aguilar didn’t learn she was dyslexic until she was almost 26.

“It was very painful,” she stated in the oral history. “How come no one else could have figured that out?”

Amelia Jones, a scholar and independent curator who included the artist’s work in a 1996 exhibition at the Hammer Museum titled “Sexual Politics,” said Aguilar was “hilarious and also very sharp” — possessing “the kind of intelligence that is clear in the work, but hard for much of the art world to understand.”

But if reading and writing proved difficult, photography was not. The camera became her outlet and her unflagging passion, a way to communicate when words often failed her.

Photography, she once stated, “became my escape.”

In junior high, after coveting her brother’s camera, she served as his dutiful darkroom assistant.

“I printed up a lot of pictures of girls playing volleyball at the net and boobs bouncing up and down,” she said with a laugh, recalling her brother’s early photos. “Then he moved on to the beach in summer [and] it was bikini tops and stuff like that.”

In high school, she finally took the photography class that her brother had demanded in exchange for the use of his gear. Her first assignment was a portrait of a basset hound in a cowboy hat. Later, at East Los Angeles College, she was a photographer for the school paper, for which she covered, among other things, local sports.

In her spare time, she snapped images of architecture and still-life arrangements drawn from objects she found at her cousin’s farm in Hemet. She especially loved to photograph children because, she once joked, “I was bigger than them and they would listen to me.”

It was at ELAC, in the mid-1980s, where she began to find her artistic voice — thanks to a Chicano Studies course taught by Venegas.

“She was this young girl — probably 19 or 20,” Venegas said. “Her mother had just died. She was very curious and she was always looking for stuff that might interest her.”

Venegas took her to East L.A.’s Self Help Graphics to see exhibitions and to Day of the Dead celebrations to learn about Mexican culture. Inspired by what she saw, Aguilar hungrily threw herself into her work.

“There was a lot of Laura’s life that was chaotic,” Venegas said. “In her photography, there was nothing disorganized, chaotic or dysfunctional.”

The years following ELAC — the late ’80s and ’90s — were a fertile time for the artist, a period in which she captured a distinct intersection of Los Angeles life, one in which the Chicano and the queer intersected.

She also explored the nooks and crannies of the human body — taking conventions of beauty that prize thin-ness and exploding them into bits.

In one series of images from 1991, titled “Nude Exercise #12,” Aguilar captures close-ups of her body without clothing: her pendulous breasts, the gently undulating folds of skin at her midsection, her tanned brown hands against a white expanse of chest — a woman both vulnerable and proud.

“She is dealing with specific issues,” explained Noriega, who first came to know Aguilar and her work in the 1990s. “But she is also doing something that pushes beyond that: She’s dealing with class, literacy and the body — and those things belong to everybody.” You are dealing with a shared experience of the human condition.”

These accomplishments did not go unnoticed. Over the course of her career, Aguilar’s images were featured in exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hammer Museum, Artpace in San Antonio and the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. In 1993, her photography was included in the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale.

But if critics were encouraging, the market was not. Aguilar made little money from her work — surviving on odd jobs, grants and the occasional residency. After the late 2000s, health and financial troubles made it increasingly difficult for her to make work.

But the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions reignited interest in topics she began exploring back in the ’80s.

“I feel Laura has done something that no artist that I know of has done in the past,” Vielmetter said. “In my opinion she is one of the great artists and one of the more important photographers of our time.”

The artist is survived by a nephew, Michael Aguilar.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Twitter: @cmonstah

ALSO

An exhibition on L.A.'s queer Chicano networks shows how California artists connected with the world

UPDATES:

11:40 p.m.: This article has been updated throughout with additional details of Laura Aguilar’s life and additional comments from people who knew the artist.

April 26, 11:50 a.m.: An earlier version of this article stated that Laura Aguilar’s parents were Grisham Aguilar and Juanita Guerrero. Their names were Paul Aguilar and Juanita Grisham.

This article was originally published April 25 at 1:20 p.m.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.