Review: Laura Aguilar at the Vincent Price museum: Turning a lens toward Latinas, lesbians and the large-bodied

- Share via

In a photographic self-portrait from 1993, Laura Aguilar stands in front of an unidentified gallery, holding a cardboard sign that reads: "Artist — Will Work For Axcess." Aguilar had been making photographs for more than a decade by then, and she has mapped the rough terrain of her inner world and cataloged the faces of under-acknowledged communities.

Pictures filling two floors of the Vincent Price Art Museum attest to her persistence, to the unvarnished honesty of her inquiry — and to the institutional access she has earned.

The retrospective "Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell" is one of the revelations brought forth by Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. The exhibition — her first full survey — could serve as the PST poster child, so vividly does it fulfill the Getty initiative's mission to tell a broader, deeper version of L.A., Latino and Latin American art history by fleshing out the plot and diversifying its cast of characters.

The show is organized by independent curator Sybil Venegas (a former professor of Aguilar's at East Los Angeles College, where the museum is housed) in collaboration with the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. It includes more than 130 works, most of them black-and-white portraits or self-portraits.

The camera democratized portraiture, making it affordable to those outside the traditional patron class. Aguilar pushes that process further by turning her lens toward photographically under-represented subjects like herself: Latina, lesbian, large-bodied.

Aguilar examines identity and belonging, the friction of feeling unworthy and the peace of reaching self-acceptance. She captions a group of portraits of women (1986-90) with their thoughts on identifying as both lesbian and Latina. In "How Mexican Is Mexican" (1990), she cannily adds along the bottom edge of each print a row of thermometers like those found on jars of salsa. Statements of ambivalence measure mild; ethnic pride raises the temperature to hot.

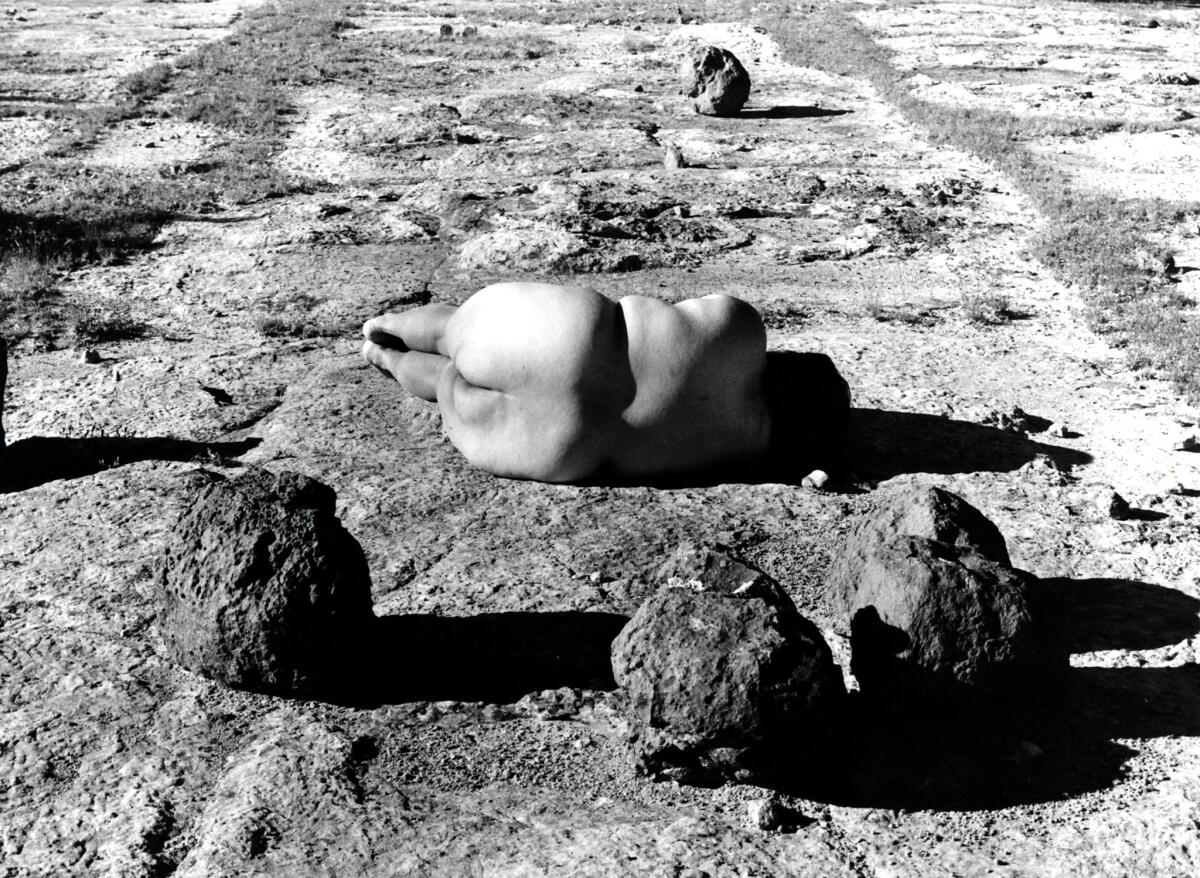

The most stirring and paradigm-shifting works are Aguilar's nude self-portraits, starting with "In Sandy's Room" from 1989. Here, she brilliantly transposes the self-consciously sexual, reclining nude of Western tradition to the unglamorized suburban present. On a hot day, she spreads her ample body beneath an open window, fan blowing directly on her, iced drink resting on her thigh. The terms of comfort are hers; she is the very image of content self-containment.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Nudes posed in nature, as nature, follow. In these scenes of Aguilar sitting among boulders and lying beside pools of water, she enacts a primal sort of belonging, where she is continuous with the world rather than at odds with it, her shape and color as right as anything of the Earth.

In a 2007 video, Aguilar speaks to the camera about her struggles with depression, fear, self-doubt, the lack of touch in her life. She stands naked, literally and metaphorically, before a wall of stone, describing how her photographs help remind her of her own capacity and beauty. Photographs, especially those that make visible what usually goes unseen, have that kind of declarative, affirming power. Aguilar has worked hard, against the current, to land on these museum walls. We are the ones graced with access.

Vincent Price Art Museum, East Los Angeles College, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park. Through Feb. 10; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 265-8841, www.vincentpriceartmuseum.org

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

MORE ART:

Ai Weiwei and the global refugee crisis

Anna Maria Maiolino and art about being a woman

Why David Geffen is pledging $150 million for LACMA’s new building

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.