Damien Hirst’s sharks: From the Met to a Vegas casino bar, artworks swim between the high and low

- Share via

The Palms Casino Resort has a secret. The Vegas hotel’s new central bar is hidden behind two layers of curtains. A burly security guard mans the entrance, warding off curious hotel guests and any gamblers who wander over from nearby craps tables.

What lies inside?

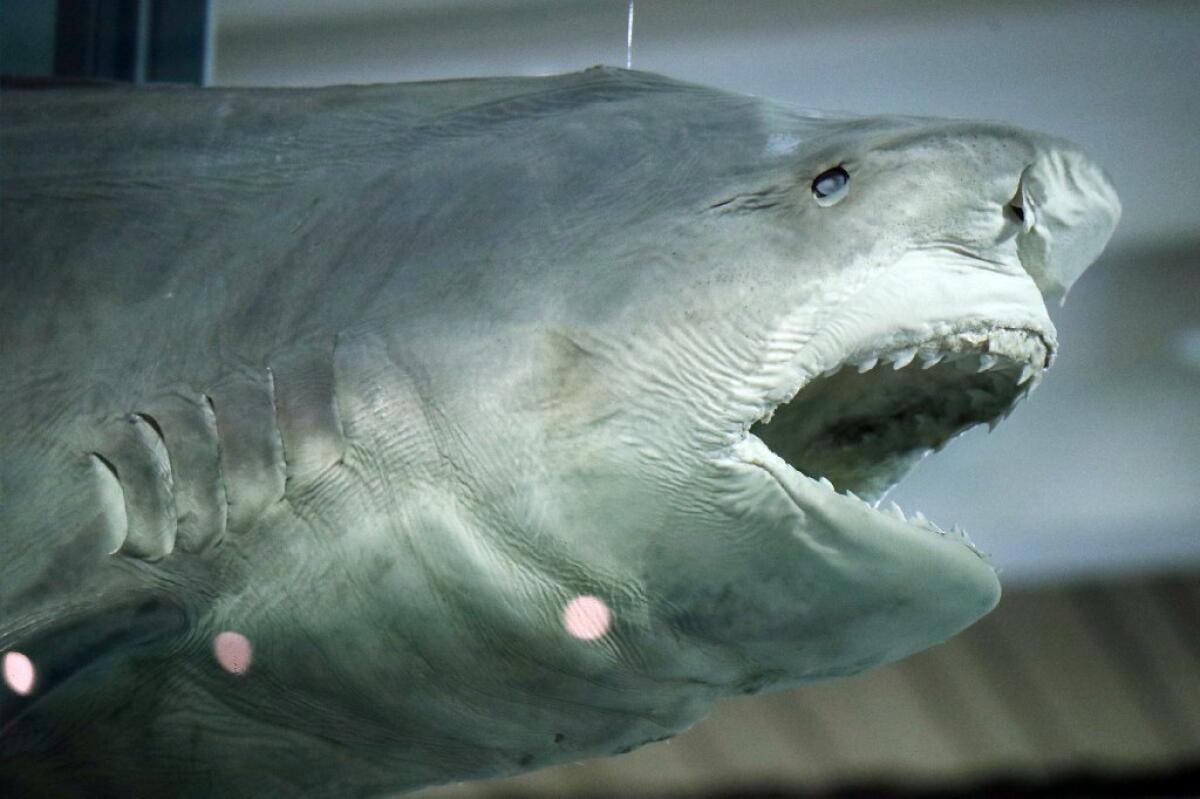

A shark, severed into three pieces. It presides over the sleek bar, each segment of flesh floating in its own steel-and-glass tank filled with formaldehyde. Paintings bearing multicolored spots hang on the walls around it, infusing the tanks with rainbow-hued reflections of dots that seemingly flow through the shark’s open, toothy mouth and around its pointed snout.

The shark is British artist Damien Hirst’s 1999 sculpture “The Unknown (Explored, Explained, Exploded),” and it swims at the Palms’ new Unknown Bar, which Hirst designed.

MORE PHOTOS: Damien Hirst's Vegas shark attack and other art at the Palms »

Palms owners Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, who sold mixed martial arts promoter Ultimate Fighting Championship for $4 billion in 2016, are fans of Hirst’s work and own many of his pieces. They purchased the tiger shark directly from Hirst, who created the piece after acquiring the nearly 13-foot-long carcass from a fisherman in Australia. It’s never been exhibited before, but versions of it have been seen in museums around the world.

Those works, among Hirst’s most iconic, are part of his “Natural History” series, which tends to stir admiration from fans and vitriol from animal rights activists. But the polarizing reactions aren’t a negative thing, says Palms general manager Jon Gray.

“That’s the whole point of art in general,” Gray says. “It evokes different emotions. Art is personal. We like that it stirs different reactions and attention.”

Beyond the ethical questions of using animals in art, the Hirst installation at the Palms raises interesting philosophical questions about art in general. What constitutes an exhibition space these days — or art itself, for that matter?

Another Hirst tiger shark tank, “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” (1991), remains one of Hirst’s most famous works. It was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 2007 to 2010 and at London’s Tate Modern in 2012. That the Hirst sharks have found themselves exhibited in some of the most hallowed grounds of fine art and now also the bar of a Las Vegas casino is a ripe dichotomy. Does it speak to the ongoing blending of high and low culture? Is Hirst once again turning something potentially esoteric into something of the people? Or is it just another sign of fine art's slide into commercialization?

“The shark is so outrageous — it’s vulgar in either situation, a museum or a casino,” art writer Dave Hickey says. “What could it possibly signify? It’s a dead shark! It’s entertainment value. He’s a seven-figure decorator. But I’ll go see it, have a cocktail.”

A Las Vegas bar, counters former Newsweek critic Peter Plagens, popularizes the art and makes sense for Hirst.

“The whole Young British Artists thing, it was all about bringing a kind of WTF, working-class aesthetic into art. The idea of a casino and Hirst could be a fortuitous marriage.”

Hirst conceived every aspect of the Unknown Bar, from the freckled, candy-colored logo and napkins to the simple coaster-dots in lemon yellow and tangerine orange, to the pill-like cocktail stir sticks tipped with scarlet, yellow and powder-blue tablets. The shark provides a centerpiece to what’s otherwise a minimalist space, with cream-colored leather banquettes and ivory silk throw pillows. Nine of the artist’s spot paintings, none displayed publicly before, adorn the walls. Seasonal cocktails, in saturate hues of blood orange and amber, complement the art.

Hirst, who’s been sober for 11 years, doesn’t even drink. But he says he was excited to design a Las Vegas bar partly because of the counterintuitive nature of the exhibition space.

“A lot of museums can feel like they’re made for dead artists — not a very exciting place to hang art,” Hirst says. “I’ve always liked how art can exist anywhere. You don’t always need white walls and a perfect white room to show contemporary art. What we’ve done here, with the Unknown Bar, the art really stands up and feels so alive.”

Of the shark, he adds: “I like the impact. When you walk in, you don’t expect it. This just shows you: Art can survive anywhere.”

Gray won’t say what the Palms paid for the Hirst shark. Instead, he points to “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” which hedge fund billionaire Steven A. Cohen reportedly paid $8 million for in 2006.

“We reference that piece when we talk about numbers. It’s about the same size,” Gray says.

The towering tanks, filled with a formaldehyde solution, occupy the middle of the oval-shaped, white quartz bar and loom over high rollers sipping cocktails. When full, the tanks weigh 15,000 pounds each. But earthquakes aren’t a concern, Gray says.

The glass on the tanks is thick and bullet proof, and the piece was engineered with seismic considerations in mind, with a drainage system embedded in the floor. Installation of the shark took more than 10 days, during which employees wore hazmat suits and inhalation masks and the bar was concealed by two layers of temporary sheetrock walls — as much to preserve the secrecy around the project as for safety reasons. The shark itself was sneaked into the bar in the middle of the night. “It was like Ft. Knox here,” one employee says.

That early Hirst shark piece, “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” was “highly attended” when it went on view at the Met, the museum says. Another tiger shark, “Myth Explored, Explained, Exploded (1993-1999),” is on view at the New York outpost of Gagosian, one of the highest profile art dealers globally. Hirst’s only great white shark, “The Immortal” (1997-2005), was last shown at the exhibition space Al Riwaq in Doha, Qatar from 2013-2014.

The Vegas casino bar may be the most populist exhibition venue for a Hirst shark yet.

“It does seem like bringing coals to Newcastle,” jokes Fabrik magazine associate editor Peter Frank. “Putting a shark in Vegas is kind of redundant, movers and shakers in Sin City. But covering the Met and the Palms Casino with one fell shark is perfect Hirst. And no longer is a casino the antithesis of a museum. A casino can be a display case too.”

Any space is appropriate for exhibiting art these days, says independent curator Brenda Williams.

“I wouldn’t want to sit at a bar and look at [the shark], but it’s an interesting idea,” Williams says. “This is Vegas, so they’re bringing in a cross section of Americans and international travelers that may not go to museums or know Damien Hirst. This might be their first introduction to him, and they may become more interested in visiting museums and not feeling like, ‘Hey, this is above my head.’ ”

Like Hirst, New York and Canadian-based artist Marc Séguin sometimes uses animal carcasses in his work, which is collected by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, among other museums. He balks at Vegas as an exhibition space for serious, fine art.

“For me, the location subtracts from it,” he says. “I'm afraid people sitting, sipping a shark bite cocktail at the bar will oversee the extraordinary qualities of that sculpture and will be blinded by the drunkenness of the settings.”

British artist Polly Morgan, who uses taxidermy to make sculptures with donated and found animal bodies, says she’d welcome being exhibited in a Las Vegas casino — but only under the right circumstances.

“If the environment was tacky and I felt the work wasn’t presented in a good light, I’d be uncomfortable, but that goes for anywhere, not just a casino,” she says. “It sounds like the Palms has invested in some good artists and are keen to show it not as a gimmick but in the context of other contemporary art.”

She adds, “As an artist, I find the greatest compliment to my work is to have people living, breathing, eating and laughing alongside it.”

Hirst has designed restaurants before, including the pill-themed Pharmacy 2, in his Newport Street Gallery in London. But the Palms project is his first U.S. bar. He worked with the hotel’s in-house design team and the architecture and design firm Friedmutter Group Las Vegas.

A center bar is the “heartbeat” of a Vegas hotel, Gray, says, and Hirst was chosen for a reason.

“The Palms is meant to be a very high energy, fun but upscale property, and the center bar has to make that statement,” he says. “One of the biggest statements that have been made in the art world and pop culture is Damien’s shark.”

The bar is part of a $620-million renovation at the hotel, and one of the distinguishing features is a collection of more than 150 pieces of contemporary art on view in public areas. During The Times’ sneak peek (the bar has since opened to the public), works by Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Takashi Murakami, Christopher Wool, Dustin Yellin and Richard Prince, as well as sculptures and paintings by street artists such as KAWS and Jason Revok, were being installed or had just been hung.

“We wanted to create something for a new generation,” says Palms creative director Tal Cooperman, who helped the Fertitta brothers to curate the project.

Expect selfies.

But the shark will be the ultimate art draw. The Unknown Bar sits by the entrance, anchors the casino floor and is a central meeting spot for guests. There’s no other art on view in the bar but for the fish and Hirst’s nine spot paintings, which amount to 16 canvases. (One work, the 2018 “Stearic Acids,” consists of eight panels.) All the paintings were newly commissioned for the hotel and are part of Hirst’s ongoing “Pharmaceutical Spot” series.

Vegas hotels are by no means devoid of art. The Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, which featured original owner Steve Wynn’s personal art collection when it first opened, has shown exhibitions by Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein; its restaurant, Picasso, has multiple works by its namesake. Down the street, the Aria Fine Art Collection features work by contemporary painters, sculptors and installation artists including Jenny Holzer, Nancy Rubins, Claes Oldenburg, Frank Stella and James Turrell.

What sets the Palms’ art collection apart, Cooperman says, is the range of artists and the level of integration in terms of where and how the works are displayed. Rather than simply hanging art on the walls or featuring sculptures in open spaces, the works have been integrated into the décor, often in unexpected places.

Pieces by Hirst and Timothy Curtis hang inside cashiers’ cages. An outdoor billboard advertising hotel entertainment also flashes digital art by Olivia Steele, Glitch and Filipe Pantone. Street art duo DabsMyla designed the in-room snack bars and “intimacy kits.” Erotic cake frosting installations by Scott Hove adorn the women’s room toilet stalls.

Hand-painted murals by James Jean blanket the Send Noodles restaurant. Yellin’s human-looking “Psychogeographies” — three-dimensional, abstract collages on stacked glass plates — stand in the center of the hotel’s Apex Social Club, like frozen nightclub-goers.

Works by Basquiat fill a private dining room in the hotel’s steakhouse. (Remember the Basquiat that sold for $110 million last year? It was Frank Fertitta who drove up the bidding war, one he ultimately lost to Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa.)

Guests will receive an old-fashioned, browned treasure map of the art locations when checking in, so they can take self-guided tours of the works.

Stage 2 of the renovation, debuting in 2019, will feature artworks in the pool area, dayclub and other restaurants. But Cooperman won’t even hint of what’s coming.

The Palms takes its secrets seriously.

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

MORE ART:

Miró masterpiece was sold to the highest bidder. It belongs in a museum instead

Enter the rainbow: Inside artist Mindy Shapero's mind-bending room

From 14 million photos in the Library of Congress, she chose these 440

UPDATES:

3:30 p.m. May 21: This article was expanded substantially with new details about the artwork at the Palms and new comments on the Hirst shark.

This article originally published at 11:25 a.m. May 17.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.