How guerrilla art on the streets of South L.A. confronts scars from the 1992 riots

- Share via

Artist Juan Capistrán was a teenager on an afternoon bus ride from Venice to his home in South Los Angeles when the 1992 riots began. Even though Capistrán noticed passengers were increasingly upset the further east and south his bus traveled, it wasn’t until he was nearly home that he learned a jury had acquitted four police officers in the beating of Rodney King.

Within an hour of arriving home, the house next door was broken into and the liquor store in his neighborhood was burned and looted. During the next week, more than 60 people died and more than 2,000 were injured amid looting and fires. Now 42, Capistrán calls the riots a defining moment in his life, lifting the veil on the pervasive inequality around him and shaping his art.

“I knew where I lived, I knew the history and all the violence around me,” he said. “But it wasn’t until that moment that I realized this is [expletive] up, what’s been happening and what I’ve been living through.”

The aftermath of the riots is the subject of Capistrán’s project “Psychogeography of Rage,” on view at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. It’s part of an exhibition showcasing winners of the 2019 City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowships, a $10,000 grant awarded by the Department of Cultural Affairs to local mid-career artists. This year the city selected 14 fellows in design and visual arts, literary arts and performing arts.

Could easily be an object of revolution, could quickly be turned to an object of destruction.

— Artist Juan Capistrán, on the power of bricks

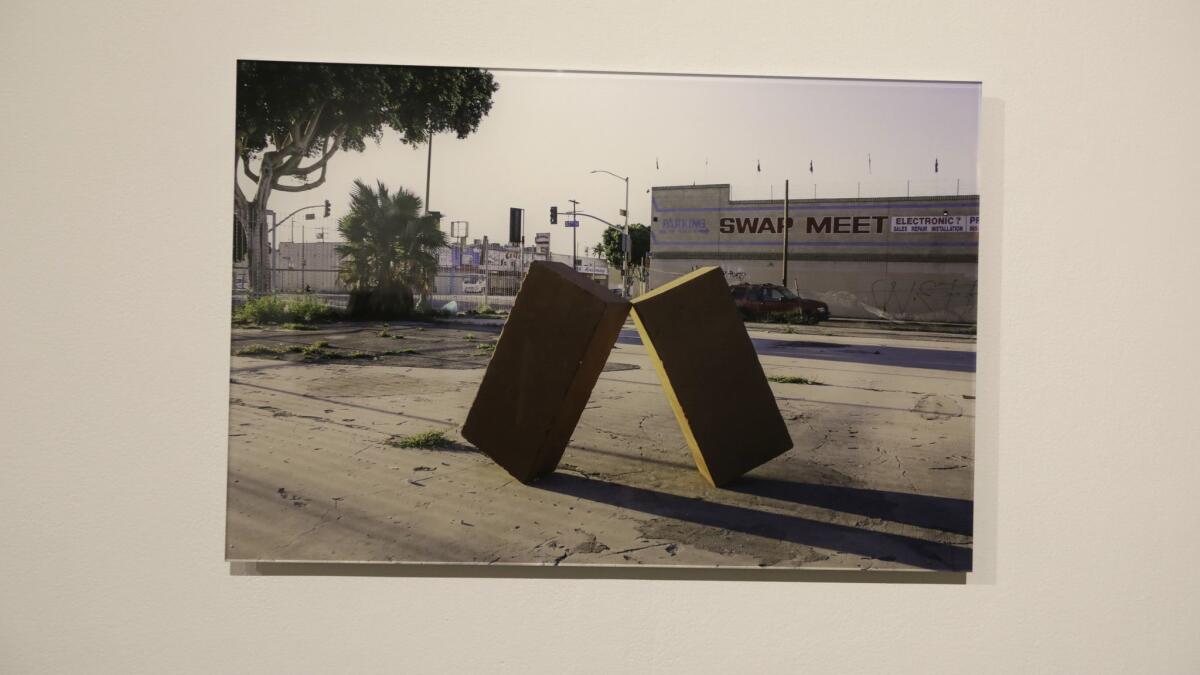

Capistrán’s COLA grant funded the beginning of “Psychogeography of Rage,” a set of reddish-brown sculptures that look like giant bricks, installed at empty lots in South L.A. — plots abandoned since the 1992 riots. The project is rooted in Capistrán’s questions about how L.A. has coped with the riots some 27 years later.

“You look around the city and there were other parts outside of South Central that were deeply affected by the riots and those got redeveloped right away,” he said. “This community, there’s huge areas that were never taken care of.”

Bricks are ambiguous, Capistrán said. They are the building blocks for constructing something new, but he also referenced Damian “Football” Williams, who was part of the mob that attacked Reginald Denny in the early hours of the 1992 riots, smashing the trucker in the head with a brick. A brick, which “could easily be an object of revolution,” Capistrán said, also “could quickly be turned to an object of destruction.”

Capistrán’s bricks are about 4 feet long and 2 feet wide and made of fiberboard, wood and paint. He installed the first ones guerrilla-style in February, working in the early hours of morning with his wife, graphic designer Hazel Mandujano, and others.

Once Capistrán installs his sculptures, he leaves them alone for nature, or human interference, to take its course. The artist chose familiar areas for the project — empty lots on streets where he roamed as a teenager including Broadway, Century Boulevard and Martin Luther King Boulevard.

To date Capistrán has created eight installations. Seven feature two of the large bricks, and one installation is a set of smaller bricks with balloon text attached. Capistrán documented each with photography or video, on view at the COLA show.

The longest-lasting sculptures were up for nearly a month. One installation tipped over, then disappeared. Capistrán found one brick completely smashed.

The project is meant to be ephemeral. While en route to the exhibition opening last month, Capistrán received a text about someone knocking over one of his sculptures created specifically for the exhibition. A day later in the gallery, the bricks — tilted precariously against one another— toppled over.

There were other parts outside of South Central that were deeply affected by the riots and those got redeveloped right away.

— Juan Capistrán

It’s part of the process, he said. “I’m not overly protective of my work in general because a lot of it tends to be either time-based or is just a document of something that I’ve done.”

Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, Capistrán grew up in a predominantly black neighborhood in South Los Angeles. He calls his story, of having to choose between joining a gang and forging a different path as a young adult, “cliche.” In the late 1980s, Capistrán started doing graffiti and his older sister began taking him to museums and galleries, further sparking his creativity.

As an undergraduate at Otis College of Art and Design, Capistrán began doing work in empty lots in South L.A. Since then his art, which often tackles political issues, has appeared at the Hammer Museum and at LACMA.

Capistrán currently lives in Leimert Park and runs a project space with Mandujano in Inglewood. It’s important that the artist is deeply connected to the community, municipal gallery curator Ciara Moloney said. “He’s not objectifying people. It’s really derived from his own life.”

Revisiting the sites of the riots more than 25 years later still fascinates him, Capistrán said — “these empty lots, these scars of these events.” As he completes more installations across South L.A., he hopes the work will force people who see it to ask questions.

“I can’t really control the interpretation of it, but I hope there’s enough clues that point the viewer in the direction I was thinking,” Capistrán said. “Hopefully it lights something in them that snowballs.”

=====

‘COLA 2019’

Where: Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Art Park, 4800 Hollywood Blvd., L.A.

When: Thursdays-Sundays, through July 14

Admission: Free

Info: (323) 644-6269, lamag.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.