Review: In postwar L.A., youth style intersected with social justice

- Share via

Style is content in the big, loose-limbed yet engaging exhibition “Tastemakers & Earthshakers: Notes From Los Angeles Youth Culture, 1943-2016.” A rough sketch rather than a fully finished picture, it nonetheless touches many provocative bases.

The show is at the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College. Like the city itself, it’s a sprawl. More than 40 artists have contributed paintings, sculptures, photographs and installations. In addition, there are street fashions, family snapshots and ephemera lifted from mass media — newspaper clippings, magazines, pop music, television clips, etc.

Style, however, is not being presented as just any form of commercial content. Instead, museum director Pilar Tompkins Rivas and her curatorial team smartly pick and choose in order to locate style within a specific narrative — a story of social justice.

Think John Waters’ “Hairspray,” albeit starting out 20 years earlier and happening in L.A., not Baltimore.

Or think playwright Luis Valdez’s “Zoot Suit.” The museum’s atmospheric show doesn’t track a formal history, but it begins in 1943 for a cogent reason: That was the year of the Zoot Suit riots.

For several weeks in June, Mexican American kids decked out in jazz-era finery were assaulted by marauding white soldiers serving in a segregated military and massed in Southern California as a bulwark against the war in the Pacific theater. The kids retaliated. Authorities let the conflict rage.

“The zoot suit has become a badge of hoodlumism,” insisted one reckless city councilman. In truth, the style was a radical sartorial emblem of distinctive cultural identity.

Pachuco style, as it is also known, began in El Paso, elaborating on African American fashion. It quickly spread along the border and finally blew up into a full-fledged phenomenon in L.A., emergent pop culture capital of America. Broad shoulders, wide shirt collars, even wider lapels, cinched wasp waists, balloon pants — the zoot suit exaggerates a voluptuous hourglass figure. Buttoned up but sexy, the look is muscular on men and curvaceous on women.

The smashing zoot suit finery on display in the exhibition’s first room asserts two early-1940s cultural realities.

First, the nearly unisex uniform of a suit — jacket, shirt and pants for him; jacket, shirt and skirt for her — demonstrates a degree of sexual fluidity operating inside an otherwise masculine-dominated social fabric. And second, the marvelous peacock drama inherent in these brash fashions represents a resolute refusal to disappear into the woodwork. To heck with expectations for public invisibility within a segregationist society.

Mexican American youth style was clashing with norms of established white privilege. No wonder the fancy fashion was picked up by Japanese American kids too, as seen in a documentary photograph taken at the Tule Lake internment camp in Northern California.

These sorts of cultural collisions recur in “Tastemakers & Earthshakers,” albeit in a variety of different forms. Some are historical, like the zoot suit display, and some curatorial.

Ricardo Valverde’s hetero-erotic photographs of enticing young Chicano women in the 1970s, for example, are juxtaposed with Dino Dinco’s homoerotic photographs of enticing young Chicano men taken in 2001. They speak to one another across time and social space.

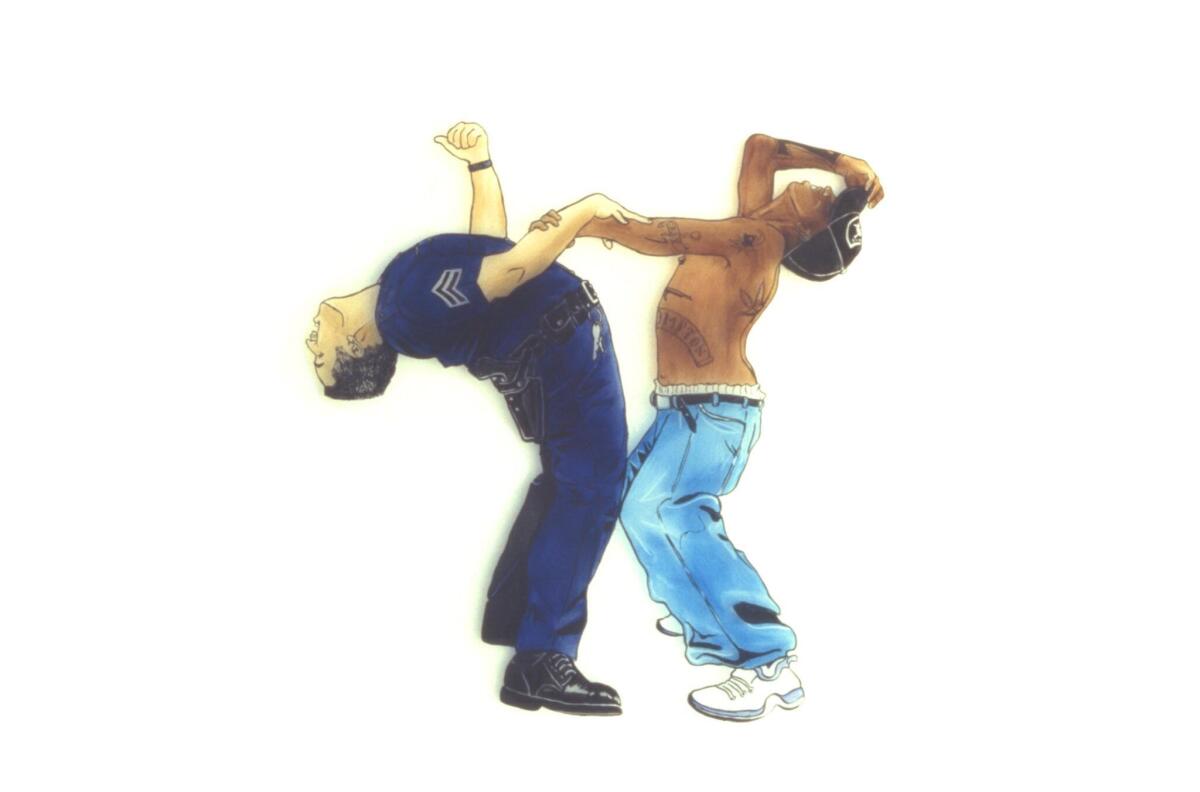

Also in 2001, Alex Donis made a series of sleek paintings on clear acrylic sheets in which brown gangbangers are shown grappling with uniformed policemen against blank, white backgrounds. Whether Donis’ incongruous duos are fighting each other in the street or dancing together rapturously at a gay club depends on your angle of vision. The works add a sharp twist of layered social conflict to Robert Longo’s well-known 1979 drawings of chic downtown Manhattanites, fashionably gyrating in empty space.

The dynamic action in Salomón Huerta’s shrewd canvas “Three Horsemen,” painted in the immediate aftermath of the 1992 L.A. riots, derives from an imperial Baroque hunting picture by Peter Paul Rubens. Huerta switched out Rubens’ mounted Arab noblemen for Chicanos on horseback, and he replaced Rubens’ exotic hippopotamus, target of the hunt, with a squealing white pig.

Point taken. The antithesis of the enigmatic portrait heads for which the artist would become widely known later in the decade, the forthright “Three Horsemen” landed on the cover of “Decolonize,” Aztlan Undergound’s barbed 1995 album.

Other portraits on view travel on a sliding scale from acutely realist to elaborately stylized. John Valadez is at one end of that wide spectrum, Carolyn Castaño at the other and Patssi Valdez somewhere in between.

Music playlists, graffiti styles, visual rhymes with British pop and punk, news clips — the show roams far and wide and in fits and starts. The most infectious sculptural installation is Juan Capistrán’s foam-core model of an ordinary domestic bungalow, which is set up inside a makeshift tarpaulin-tent — the kind a street vendor might use, or a backyard tinkerer.

Dance music and pulsing party lights emanate from Capistrán’s cozy bungalow — a modest suburban home that, on closer inspection, has been transformed into a giant boom box, its roof an exuberant plane of vibrating speakers. Irresistible, the 2010 sculpture is titled “This Machine Kills Fascists, or Labor Sets You Free (Love Is the Message).” A better, timelier expression of the exhibition’s spirit is difficult to imagine.

Vincent Price Art Museum, East Los Angeles College, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park, (323) 265-8841, through Feb. 25. Closed Sun. and Mon. www.vincentpriceartmuseum.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

UPDATES:

Jan. 12: This article was updated with additional details about the work in the lead photo.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.