Review: 3 Velázquez paintings alone are reason to go, now, to this San Diego show

- Share via

Reporting from San Diego — Think of Spain’s Golden Age, and the paintings produced in Seville and Madrid in the 17th century by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez can crowd out everything else that might as easily come to mind.

The expressionist abstraction of a flamelike St. Peter in a roiling landscape by El Greco, the Crete-born Doménikos Theotokópoulos? His studies in Venice and Rome made him a remarkably modern internationalist when he got to Toledo, Spain.

The ascetic sophistication of a life-size figure of a meditating St. Francis inside a lonely cell, clutching a skull to his breast, by Francisco de Zurbarán? Riveting.

You might wince at a gauzy image of Mary Magdalene, pleading on her knees for heavenly absolution, by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, who loved going over the emotional top. Yet the sheer painterly skill of his theatrical extravagance is undeniably impressive.

Still, it’s Velázquez who has earned broad acclaim as ranking among a handful of the greatest European painters who ever lived. Along with the aforementioned works by El Greco, Zurbarán, Murillo, plus 47 other artists, three Velázquez paintings are at the San Diego Museum of Art in “Art & Empire: The Golden Age of Spain.” Even if there weren’t other compelling reasons to see the exceptional exhibition — and there are — these would be enough.

Two are fine, modestly sized aristocratic portraits, source of the artist’s bread and butter. Both show Philip IV of Spain, the Habsburg king who was Velázquez’s great patron.

In the first, Velázquez establishes a standard composition: A chest-length sitter dressed in black is seen in three-quarter view before a neutral background. The dark impersonality of these elements provides dramatic contrast for the fleshy, breathing vivacity of the subject’s carefully modeled head.

For good measure, Velázquez has set the teenager’s cabeza atop a very wide, exquisitely precise flared collar, like a jug set down on a tabletop or a melon on a plate. You can be forgiven for thinking that the composition recalls the divine head of John the Baptist resting on a platter, severed at the command of Herod in a futile quest to derail the Baptist’s growing power in the Roman Empire.

How would that gruesome thought fit a young monarch? No one was more powerful than Philip IV, whose own sprawling empire encompassed more of the world than any other in recorded history. An aura of Christian sacrifice drifts through the portrait’s composition.

The second shows Philip about 30 years later, near the middle of the century and toward the end of his life (he died in 1665 at age 60). His eyes more deeply set, neck softened by jowls and lips crowned by an upturned mustache, he’s been through a lot.

That includes oversight of Spain’s role in the Thirty Years War, which rained more gruesome death and destruction than anything before it in Europe. Velázquez and Philip were near contemporaries, the artist just six years older than the king, and one remarkable feature of the portrait is the intensity with which the ruler seems to be scrutinizing the ruled, who is painting him. Velázquez returns the favor.

The portraits are outstanding, but it’s the third Velázquez that demonstrates why he deserves such respect. This unusual work, on loan from Dublin’s National Gallery of Ireland, combines portraiture, still life and religious narrative in a single rectangular canvas just under 2 feet high and twice as wide.

A young scullery maid of African descent (perhaps an enslaved Moor) is at the center of the scene. She tidies up the kitchen while, behind and to the left, a window opens onto a miraculous event happening in the next room. The risen but incognito Christ is revealing himself to two stunned disciples.

The story of divulging the resurrection to the faithful during a supper at Emmaus is nearly a dashed-off oil sketch, tucked off to the side. Velázquez inverted the focus, now aimed at the kitchen help’s response to the key religious event.

Torso bent slightly over the table where she’s just finishing putting away the dishes, the young woman cocks her ear toward the window as if straining to overhear the astounding disclosure. Moors were systematically evicted from Spain between 1609 and 1614, but those who were enslaved could stay if they converted to Christianity — which might explain the narrative of this picture, painted just five years later.

The palette is neutral — a broad, seemingly limitless array of browns, grays, blacks and whites. The bowls, pots, jugs and plates, plus a woven basket of linens hung at the upper right and a crumpled cloth laid on the table, are facing every which way.

It’s as if Velázquez is practicing perspective techniques and tonal range — which he might well have been doing, given that this erudite painting was executed when he was about 18. It’s his earliest known work.

The boyish artist had studied for roughly six years — mostly with his future father-in-law, Francisco Pacheco, a modestly talented artist represented in the show by a manuscript drawing. That a youthful painting exercise could be so formally and conceptually virtuosic foretells the greatness that was to come.

Velázquez could have overwhelmed “Art & Empire” — if more examples of his hard-to-borrow work had been assembled. And, more to the point, if Michael Brown, the museum’s ambitious curator of European art, hadn’t done something unusual: In considering Spain’s Golden Age, he chose to assemble art produced across all the vast Habsburg empire, not just on the Iberian Peninsula.

According to the show’s fine catalog, this is the first time an American museum has considered Spain’s colonies within the Golden Age rubric. One hundred and nine paintings, sculptures and decorative objects (ceramics, furniture, jewelry, liturgical pieces, etc.) represent every corner of the empire. Like Velázquez, the curator includes the main event; but he also looks away, curious to see what was going on elsewhere.

Madrid was the Habsburgs’ international capital. But the empire encompassed parts of the Netherlands, Italy, the Philippines (named for Philip II), the Viceroyalty of Peru, much of the Caribbean and New Spain — an expansive region stretching north from Central America across Mexico to the modern Southwest, just past Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Velázquez was emblematic. Born in Seville, the Andalusian city through which most imperial trade flowed from colonies around the globe, he borrowed the kitchen painting’s inversion of traditional religious emphasis from Flemish art.

The San Diego Museum of Art’s own distinguished Spanish collection is an anchor. There are its famous, incomparable Juan Sánchez Cotán still life, in which ordinary market fruits and vegetables seem to crystallize in vivid space; the El Greco “St. Peter”; a princely portrait by Sofonisba Anguissola, born in Italy and one of the few women to work at the Madrid court; four Zurbarán paintings; and nearly a dozen more.

Fifteen works were lent from the prominent Spanish Colonial collection at the Denver Art Museum. Others come from major institutions internationally, including in Mexico City, London, Lisbon and Madrid.

There are famous paintings, such as Miguel Cabrera’s full-length portrait of the great lesbian poet and Mexican spiritual thinker Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, surrounded by books in her 4,000-volume library. A Flemish tapestry woven by Jan Raes I after an oil sketch by Peter Paul Rubens (also from SDMA’s collection) slyly transforms a garland of roses into a chain of popes’ portraits, held by an allegorical figure symbolizing eternity. The roses are now a kind of papal rosary, cementing pontifical power for all time.

Sculpture, often neglected in shows like this, is given its due with nine examples.

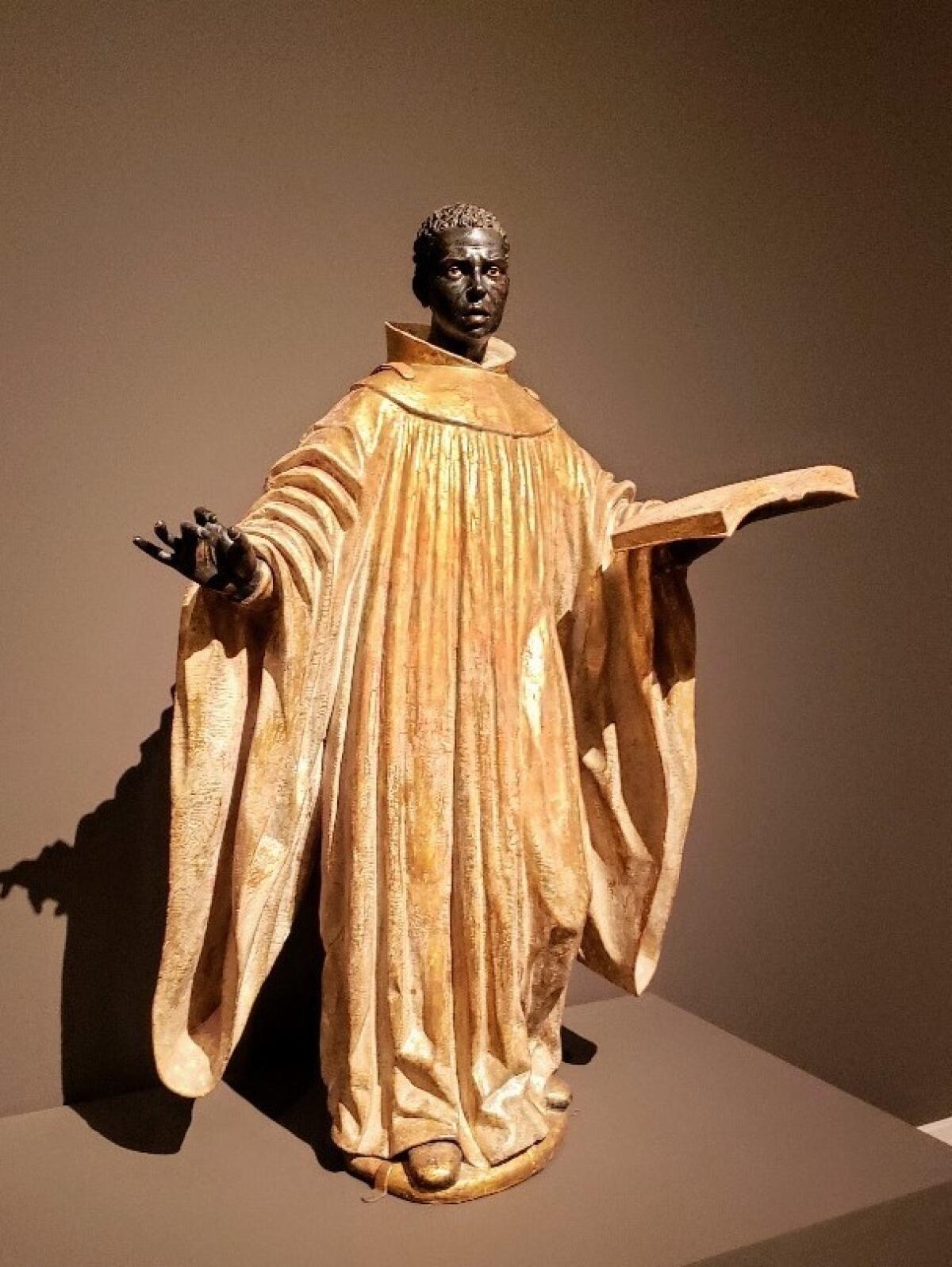

Attributed to José Montes de Oca, a ravishing, 4-foot-tall polychrome wood figure of St. Benedict of Palermo, son of freed Ethiopian slaves, seems poised to lift off into the stratosphere on voluminous gilt robes. He’s a Baroque Rocketman.

In a large, spectacular ivory carving of the crucified Christ, the curve of the tusk was exploited for drama by an unidentified Spanish artist, known as the Master of Guadalcanal. The arc creates a hip- and head-thrusting swoon.

The show is loosely organized into overlapping sections on portraiture, stylistic naturalism, religious subjects and aspects of daily life. One drawback is that the physical territory under review is so vast that only the surface can be skimmed. (The Philippines gets shortest shrift, with just two small but fine ivory carvings stashed in a vitrine by the exit.) At least twice the number of works would be needed to do the topic justice.

Still, Spain has always been a bit of an outlier in European art history, partly because of its peninsular geography and partly because of its 20th century instability. Its colonies in the Americas and the Pacific have been even farther afield. Shifting attention toward colonial era crosscurrents is its own worthwhile benefit, and “Art & Empire” takes that essential step.

=====

‘Art & Empire: The Golden Age of Spain’

Where: San Diego Museum of Art, 1450 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego

When: Through Sept. 2; closed Wednesdays

Info: (619) 232-7931, sdmart.org

ALSO

How guerrilla art on the streets of South L.A. confronts scars from the 1992 riots

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.