‘Blue Boy’ revisited: The Huntington is saving its 18th-century masterpiece — and you get to watch

- Share via

There’s a mystery unfolding at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

It involves a boy, a dapperly-dressed preteen who’s lived all his life in the public eye but whose true identity is still hazy. It also involves an unnamed man, a shadowy figure who reveals very little of himself. And a dog. And a perhaps violent episode, occurring long ago, that once threatened to destroy an invaluable masterwork painting.

This is the story of “The Blue Boy,” Thomas Gainsborough’s 18th-century portrait of a rosy-cheeked boy in a blue satin suit — his identity is unknown, but the artwork itself is one of the most iconic in the Huntington’s collection. It’s nearly 250 years old and in need of some care. So the Huntington is embarking on the most ambitious restoration of the painting in nearly a century, and much of the conservation work will be done in public view as part of a year-long exhibition opening Sept. 22: “Project Blue Boy.”

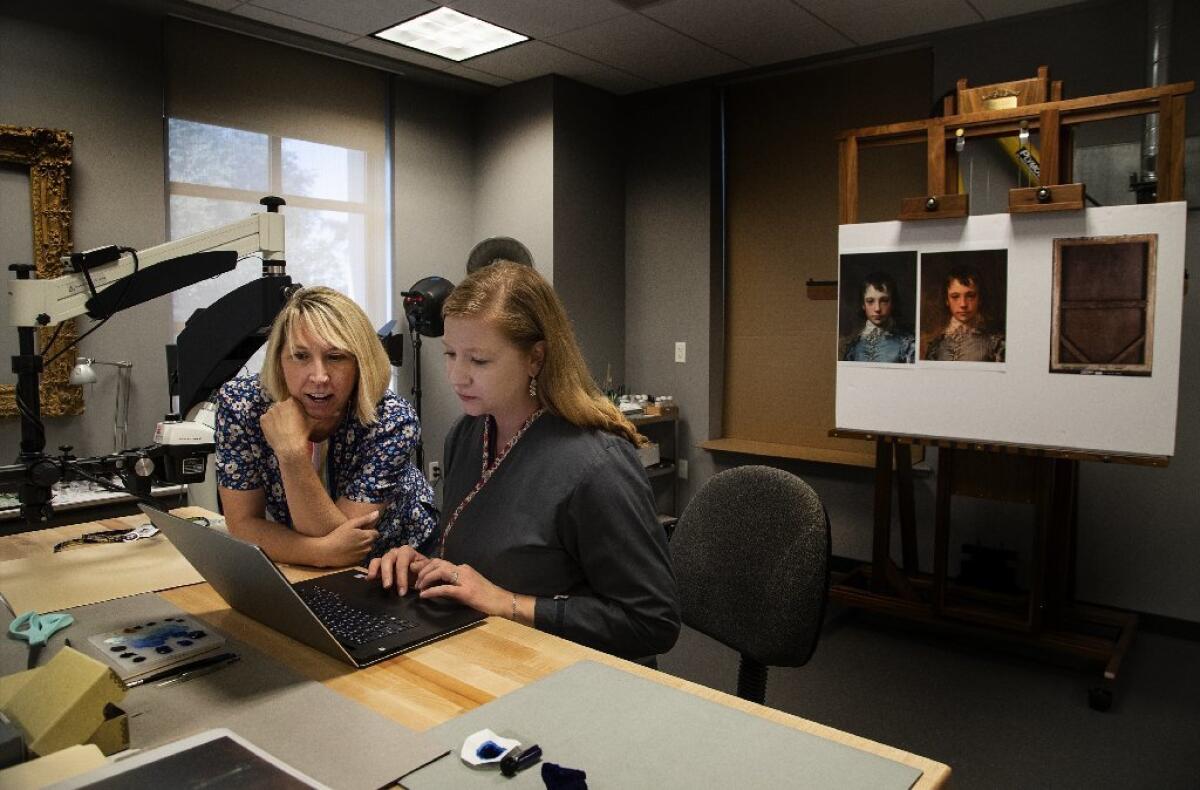

But before brush even hits canvas, in the months leading up to the conservation treatment, the Huntington’s eagle-eyed Christina O’Connell and Melinda McCurdy – something of a Cagney & Lacey of the art conservation world – are conducting extensive technical analysis on the painting. The art conservator and curator, respectively, are using high-tech imaging techniques to scrutinize the painting’s surface, deconstruct the materials Gainsborough used and study the makeup of the canvas itself and its structural backing.

This will help them assess the artwork’s needs and plan their conservation approach. But they’re also unearthing clues along the way – studying earlier Gainsborough sketches, beneath the painting’s surface, that are only visible with x-rays, for example, or breaking down the chemical composition of the painter’s pigments – that will help the art detectives answer broader questions about how Gainsborough worked and the life of the portrait after it left his studio.

“There are a lot of parallels between conservation science and forensic science,” O’Connell says, eyeing “Blue Boy” hanging at the head of the Huntington’s handsome, oak-paneled Thornton Portrait Gallery. The painting is currently on view, but will soon come off the wall for the exhibition, which O’Connell and McCurdy co-organized. “We sort of look, forensically, at all the physical clues — if we don’t have a [past conservation] report that tells us the data, then we look for it in the materials.”

Like a CSI investigator, she adds: “We take the tiniest sample possible, to get the most information, and then try to preserve the sample; we don’t want to contaminate it.”

Beyond the surface

During their preliminary analysis of “Blue Boy” in fall 2017, O’Connell, the Huntington’s senior paintings conservator, and McCurdy, associate curator for British art, made at least one new discovery and deepened their understanding of others. Through new digital technology involving a composite of 25 high resolution X-rays — game-changing techniques, McCurdy says, compared with the more basic medical X-rays on film that were used in recent decades — they discovered a repaired, 11-inch-long tear in the canvas. The fibers around the L-shaped tear are somewhat brittle, suggesting the tear happened on a canvas with some age to it; but seeing as the protective backing is not torn, the tear must have taken place before it was lined.

“We can create a timeline,” McCurdy says. “It’s our best guess without concrete evidence, but it probably happened in the early 19th century.” The painting, she adds, was exhibited a number of times in England then, when it was in the collection of the Duke of Westminster, and she speculates the tear might have occurred when it was in transit.

“My work is done when you don’t see it.”

— Christina O’Connell

A 1994 X-ray of the canvas revealed the image of a small dog that Gainsborough painted over before finishing the artwork. His process was more of a mystery until now. New infrared reflectography images, which render certain pigments transparent, reveal more detail about how Gainsborough went about covering up the now-erased dog.

“We can see how he very intentionally added layers on top of it to hide it into the landscape,” O’Connell says. “He turned the dog’s paws into rocks.”

Solving the identity of the little boy who posed for Gainsborough isn’t something McCurdy thinks will occur just yet – there aren’t enough clues and, without archival documentation such as letters or a portrait sitter invoice, the identification of the figure remains subjective. One 19th-century hypothesis was that the “Blue Boy” model was Jonathan Buttall, the painting’s first owner; a current theory is that it was Gainsborough’s nephew and studio assistant, Gainsborough Dupont.

While O’Connell and McCurdy may not solve this particular question, they do hope to learn more about a different Gainsborough portrait subject. Artists throughout history often reused their canvases. Late 1930s-era X-rays of the top portion of “Blue Boy” reveal the unfinished portrait of a man Gainsborough painted before re-priming the canvas and starting “Blue Boy.” He painted the face and a tightly wrapped shirt collar and sketched the shoulders before abandoning it.

“We’d really like to know more about who the sitter is,” O’Connell says. “We’re going to continue to do imaging to get any more detail we can. We might be able to compare his likeness to other portraits out there. But the challenge is, we don’t know if the other artists’ portraits were accurate, and there are no photographs.”

Undoing damage

“Blue Boy” has been conserved six times since the Huntington acquired it in 1921. But because it’s so beloved by the public, the museum’s priority each time was to minimize interruptions in its display life. So previous conservations have been quicker, temporary fixes mainly involving touching up the original paint where it was worn, or thinning out — rather than removing — old varnish layers and applying new ones to keep the work looking bright.

This time around, “Blue Boy” will get a comprehensive aesthetic and structural overhaul. The painting is known for Gainsborough’s unique, animated brush work and how he captured light on the textured fabric. But “Blue Boy’s” paint is flaking off in places — not identifiable to the naked eye, but still detrimental to the artwork. Dirt is trapped between the many layers of varnish, dulling the painting’s contrast and muting its colors; and the varnish layers themselves have discolored with age. The lining canvas – a blank canvas fastened to the back of the original one for stability — is coming unglued and the painting’s original wooden stretcher has fine cracks and loose knotholes on it.

“It’s all about understanding the materials Gainsborough and past conservators used and how they’ve aged over time so we know how to treat it,” says O’Connell, who has a background in fine art and chemistry with a master’s degree in art conservation.

During the first three to four months of the exhibition, “Blue Boy” will lie on a flat table or sit on an easel in a temporary conservation studio at one end of the Thornton gallery as O’Connell works on it, on select days, with cotton swabs and tiny, fine-point brushes. At this stage, she’ll be focused on surface concerns – cleaning it, removing past conservators’ varnish and overpaint that no longer match Gainsborough’s original colors, much of it only visible to her through ultraviolet illumination — as well as “paint stabilization,” in which she’ll set down flaking paint with custom-mixed adhesives.

As O’Connell works, a 6-foot-tall surgical microscope on wheels will roll around the canvas with her, projecting what she sees onto a large screen so that visitors can watch her work. The public will be free to ask her questions during predetermined sessions. An adjacent exhibition will offer history about Gainsborough and “Blue Boy” — Henry E. Huntington purchased it in 1921 for a record-breaking sum at the time of $728,000 — as well as details about the field of art conservation. Hand tools, paint samples, a schematic of “Blue Boy’s” material layers and the most current digital X-rays of the artwork will also be on view.

The messier, more laborious structural work, such as repairing the wooden stretcher and reaffixing the lining canvas, will take place privately over the next three to four months in O’Connell’s lab. Then the artwork will return to the public lab for final conservation, during which O’Connell will do “in-painting” on tiny areas of the canvas, paying careful attention to texture and opacity while adding modern conservation colors to match Gainsborough’s. “Carefully hiding the damage,” she says. “My work is done when you don’t see it. Because I don’t want to alter the painting at all. I just want the painting to be read and understood the way it should be.”

Transparency, such as visible storage or indoor-outdoor architecture, has been a trend at museums for years, and conducting art conservation in public is no exception. The Museum of Contemporary Art in collaboration with the Getty Conservation Institute has this year been publicly conserving Jackson Pollock’s “Number 1, 1949” (1949); the Dallas Museum of Art has permanent open conservation labs.

McCurdy says the trend is not only educational, in terms of conservation science, but rounds out the very definition of what a museum is.

“We’re not just an institution that puts beautiful things on the wall and has people come to see them,” she says. “We’re also responsible for the long-term care and preservation of the materials.”

In early 2020, the newly restored “Blue Boy” will return to its prominent spot in the Thornton Portrait Gallery.

In the meantime, O’Connell says, “We’re gonna continue to study the painting throughout this whole exhibition. Who knows — there might be more discoveries to be made.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.