‘Urban Light’: Everything you didn’t know about L.A.’s beloved landmark

- Share via

You can thank Max.

One afternoon in 2000, artist Chris Burden was wandering through the Rose Bowl Flea Market with his friend Paul Schimmel, then chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Schimmel’s son Max, 11, came running over, excited about a vendor selling vintage street lamps, which were disassembled and strewn across the ground.

Check them out, Max urged.

And that’s how Burden found the first street lamps that would form his “Urban Light” installation, now at the entrance to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The artwork, one of the city's most popular landmarks, turns 10 this month. To mark its first decade, the museum has switched from incandescent light bulbs to LEDs, a birthday gift from the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation.

It’s something that the late Burden’s wife, Nancy Rubins, said would have pleased the artist.

“Chris was a super proponent of the environment and that LEDs can be found, now, to the exact same light and intensity and color and tone that the initial light bulbs gave off, I think it would be marvelous for him,” she said. “Because that’s what drew him to the piece. It was light.”

Environmental concerns aren’t the only reasons behind the switch to LEDs. For that and other surprising facts behind the design and operation of “Urban Light” — Did you know that the lamps are set by an astronomical timer? — we’ve pulled together some fun facts about LACMA’s most popular artwork.

Just how many lights are there?

“Urban Light” has 202 street lamps. The total number of bulbs is 309 because some lampposts have two globes.

Who decides when the lights go on and off?

“Urban Light” goes on every day at dusk and blinks off every day at dawn, guided by an astronomical timer that automatically adjusts to local sunrise and sunset. It hasn’t missed a single night since it was installed on Feb. 8, 2008.

Are the lamps authentic or replicas?

Burden collected authentic, cast-iron lamps, all from the 1920s and ’30s. He sandblasted, powder-coated, rewired and otherwise repaired them in his Topanga Canyon studio.

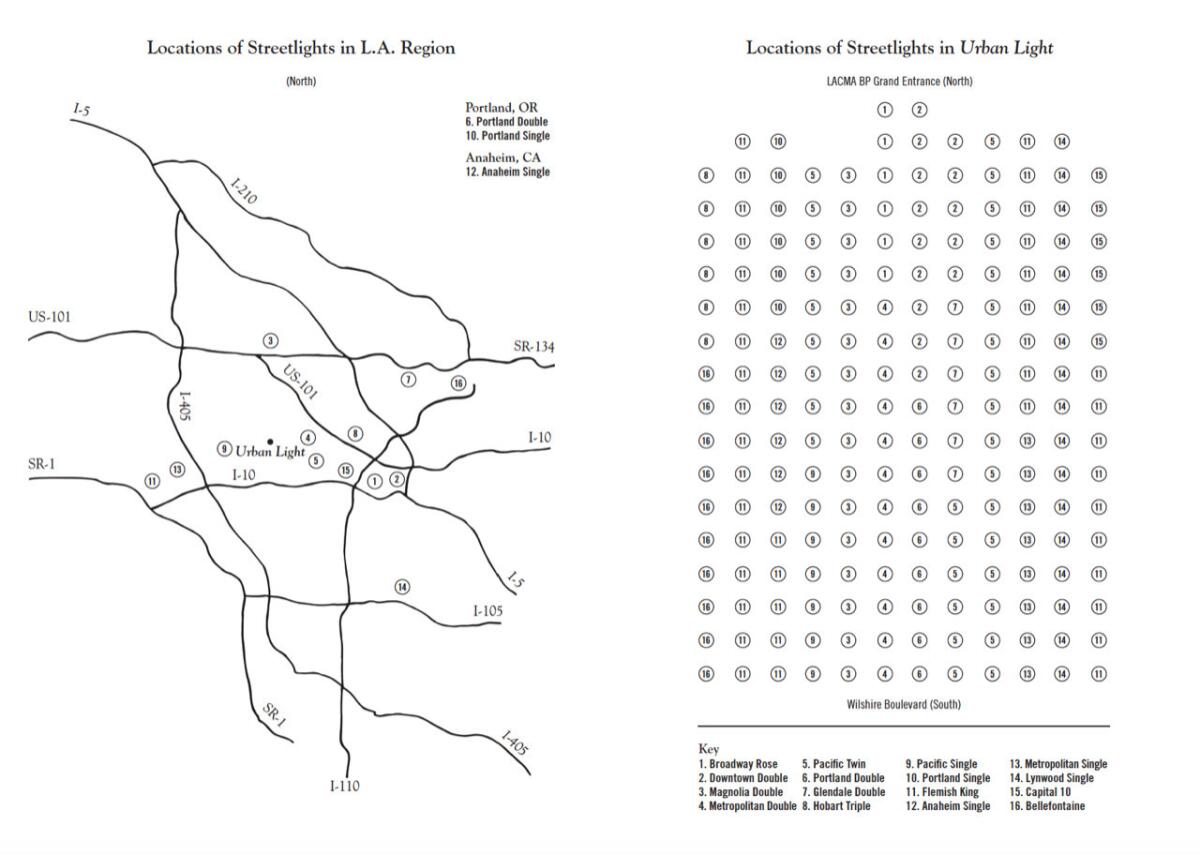

Are all the lights the same?

There are 16 different lamppost designs in the installation. The globes atop each lamppost vary in shape and size — round, acorn and cone. The acorn-shaped globes are not made anymore, so LACMA scours the city and stockpiles them in case one needs to be replaced.

The lights come from neighborhoods mostly in Southern California. In 2008, in a public conversation with Burden, LACMA Director Michael Govan talked about how the lampposts were distinctively of Los Angeles:

“I remember being incredibly amazed by them and knowing that they had to be in Los Angeles,” he said. “Because, in so many ways, they were the representation of the whole county, with each city responsible for designing its own lamps. Each lamp, then, was an expression of that city’s design; they were public art. And of course they’ve now created this image through their density.”

Are any of the models you see in “Urban Light” still in use?

Yes. Each lamp in the sculpture — with names like the Downtown Double, Hobart Triple and Flemish King — is still in use in L.A. County, Anaheim in Orange County or in Portland, Ore.

Did the artist have a favorite?

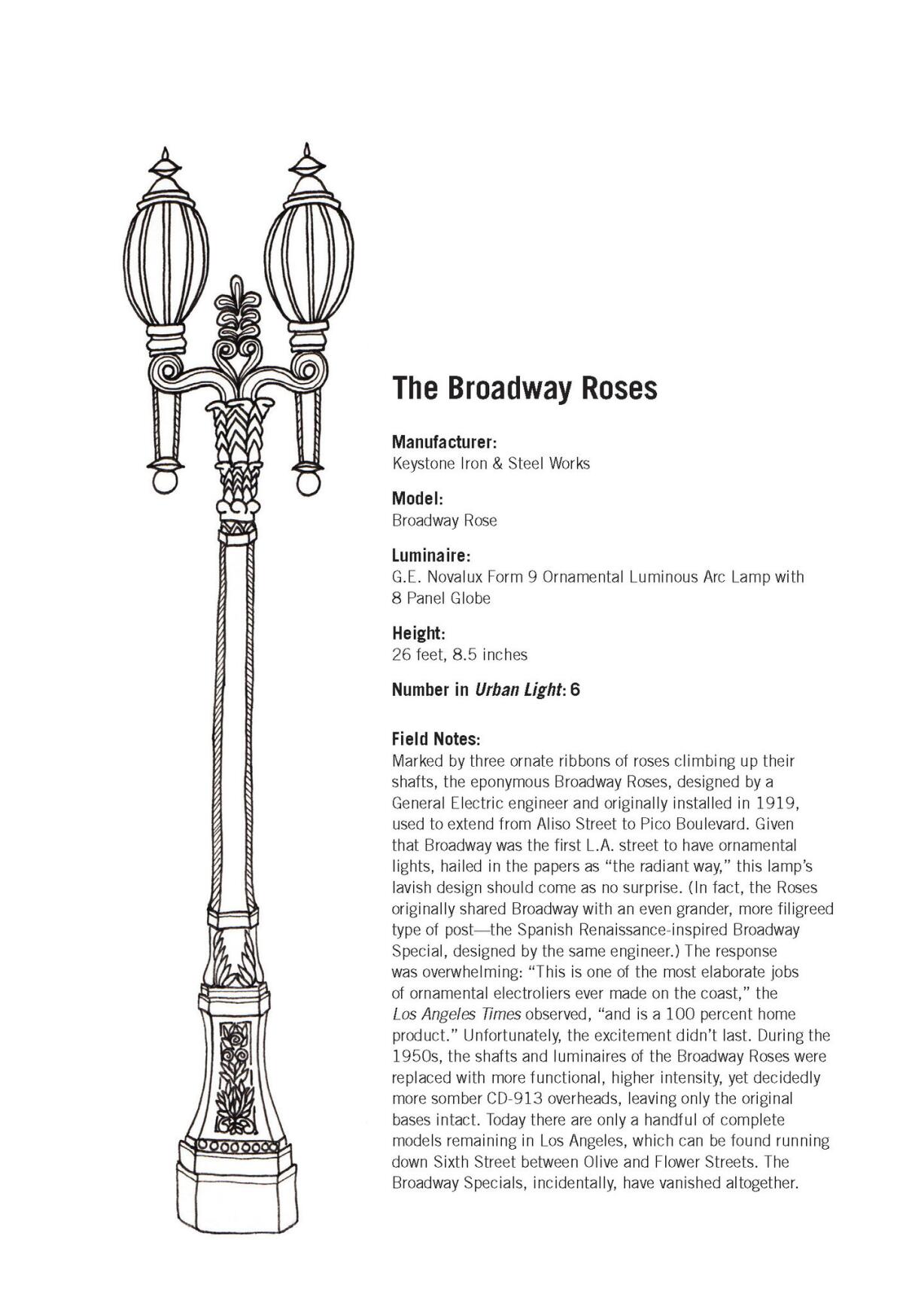

One of Burden’s favorites was the Broadway Rose, named for the rosebuds on its finial ornament on top of the globes.

How difficult is the artwork to maintain?

The lamps are cleaned quarterly. Cases of vandalism, such as lipstick marks and gum, are addressed immediately. Bulbs are replaced as needed. It’s complicated — but we’ll get to that in a minute.

What propelled “Urban Light” to such stardom?

Social media. Images of “Urban Light” have flooded Facebook and Instagram — luminescent lovers embracing, selfie stick-wielding tourists hugging its posts, yoga poses, perplexed pets.

The hashtag #urbanlight has been posted more than 34,000 times on Instagram. And then there are the people who get the artwork’s name wrong and use the hashtag #urbanlights — that appears more than 87,000 times.

Who started the phenomenon?

The first person known to take a selfie at “Urban Light,” four days after it opened, was Diana Felszeghy. She posted her picture on Flickr.

And then, eventually, Hollywood came calling?

Exactly. The artwork has appeared in several films, including "No Strings Attached" and “Valentine’s Day.” It was in an episode of “Modern Family” and has been in TV commercials too, including one for Guinness beer.

What are some of the craziest things visitors have done at “Urban Light?”

“People do séances there,” says Mark Gilberg, formerly director of the museum’s conservation center. “They light fires and do crystal worshipping there. Just go over there at midnight. People wanna climb it.”

Gilberg has even seen people strip naked and take selfies. “Like, why?” he asks.

Though it’s not rented as an official wedding site, many couples have exchanged vows in front of “Urban Light” — and captured the moment in photos.

As part of the artwork’s anniversary, LACMA commissioned Siri Kaur to shoot portraits of people who marked personal milestones at the installation and shared their photos on social media. Kaur’s portraits, which provide a where-are-they-now update, are on view in the Art Catalogues Bookstore of the museum’s Ahmanson Building.

How many conservators does it take to change a light bulb?

Two. A couple of people spent five days on scissor lifts and boom lifts to replace the incandescent light bulbs with LEDs.

How much did all those LEDs cost?

A little more than $26,000.

Why switch to LEDs, besides the obvious environmental advantages?

The switch to LEDs, which are entirely solar-powered, amounts to a 90% power savings for the museum, but beyond the environmental considerations was the issue of safety.

The incandescent bulbs were extremely hot — upwards of 350 watts, compared with LEDs that are a maximum 27 watts. Also, their protective globes aren’t water-tight. A cold rainstorm can prompt 10 to 15 bulbs to blow out, says Gilberg.

Replacing those blown-out bulbs was time-consuming, he says. Some of the rows between lampposts are only 2 feet wide, making ladders impractical. Repairs had to be made using a scissor lift. “And the ones that burn out happened always to be in the center — Murphy’s law!” Gilberg says.

Just how complicated was the switch?

It took about two years to figure out which LEDs would best match the quality of light that the artist intended — the same brightness, tone and glow.

What will happen to “Urban Light” once construction begins on LACMA’s new building? Will it move to accommodate the new Peter Zumthor design?

During construction, expected to begin at the end of 2019, “Urban Light” will be protected but not moved. Burden’s installation will remain in its current location, LACMA said, even after the new building opens in 2023.

How is that possible when some nearby buildings are slated for demolition?

The artwork was designed to be tough — and with earthquakes in mind. The poles are bolted into a concrete foundation, and the globes sit on neoprene sleeves that act as shock absorbers. With an expected lifespan of 10 years, those LEDs will still be working when the new LACMA reopens.

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

FROM THE ARCHIVES: MORE ‘URBAN LIGHT’

Chris Burden dies at 69: artist's light sculpture at LACMA is symbol of L.A.

LACMA's well-known 'Urban Light' will go dark for two months

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.