A writer apologized to me — 23 years later. A ‘waterfall’ of memories ensued

- Share via

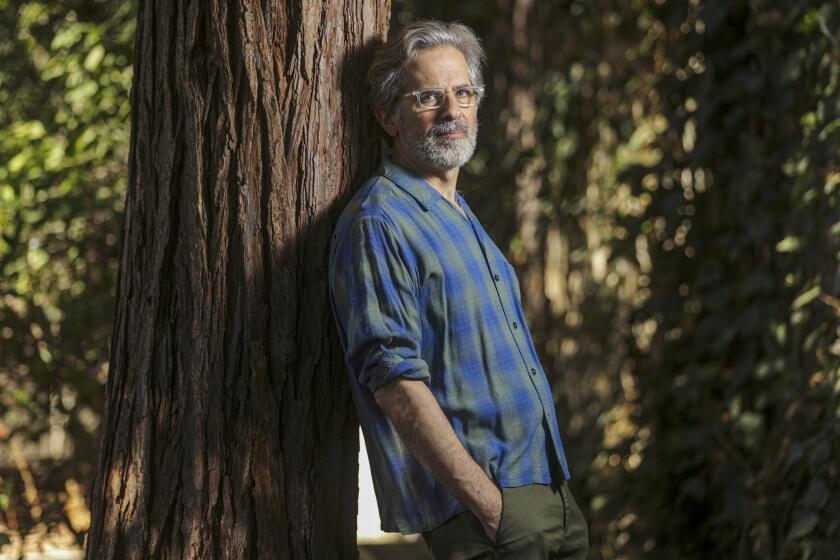

Once, long ago, in the now-shuttered offices of LA Weekly on Sunset Boulevard, I was assigned to profile a young, hip writer named Thomas Beller. The year was 2000.

Things did not go so well.

Beller was on a national book tour for his debut novel, “The Sleep-Over Artist.” I didn’t know this, but he was going through a rough time personally. He didn’t know this, but I was going through a rough time personally — headed toward a divorce. We met (eventually — more on that later) at the Hollywood Hills Coffee Shop, on Franklin Boulevard under the looming Hollywood sign.

It was so long ago that I didn’t yet have a cellphone. Beller didn’t show up right away for our interview, and I, a newbie journalist working on one of my first big profiles, sat in a booth, with his book on my lap, for an hour and a half.

I have no idea why, but I also remember the song that was lodged in my head as I waited, an old Bangles earworm my then-husband had included in a mix of oldies he’d burned onto a CD for me: “Manic Monday.”

The novelist perhaps most associated with Brooklyn lives in Claremont and has a delightful new dystopian novel out, “The Arrest”

Beller left me a succession of “Almost there” messages on my work voicemail, which I returned from a public pay phone (that thing on the wall with the shiny cord), each time getting his clipped voicemail.

Things went south from there.

When the native New Yorker finally arrived, he was not-so-nice. You can read about that here, because that became the gist of the story, published under my maiden name.

Why am I rehashing all this? Because Beller reached out to me last week — 23 years later — to apologize.

Beller is director of creative writing at Tulane University. His academic bio says that his work, while spanning genres, is bound by an interest in “the dynamics of relationships,” as well as “the nature and effect of time.” So I found his two-decades-late apology curious, but oddly fitting. Almost poetic.

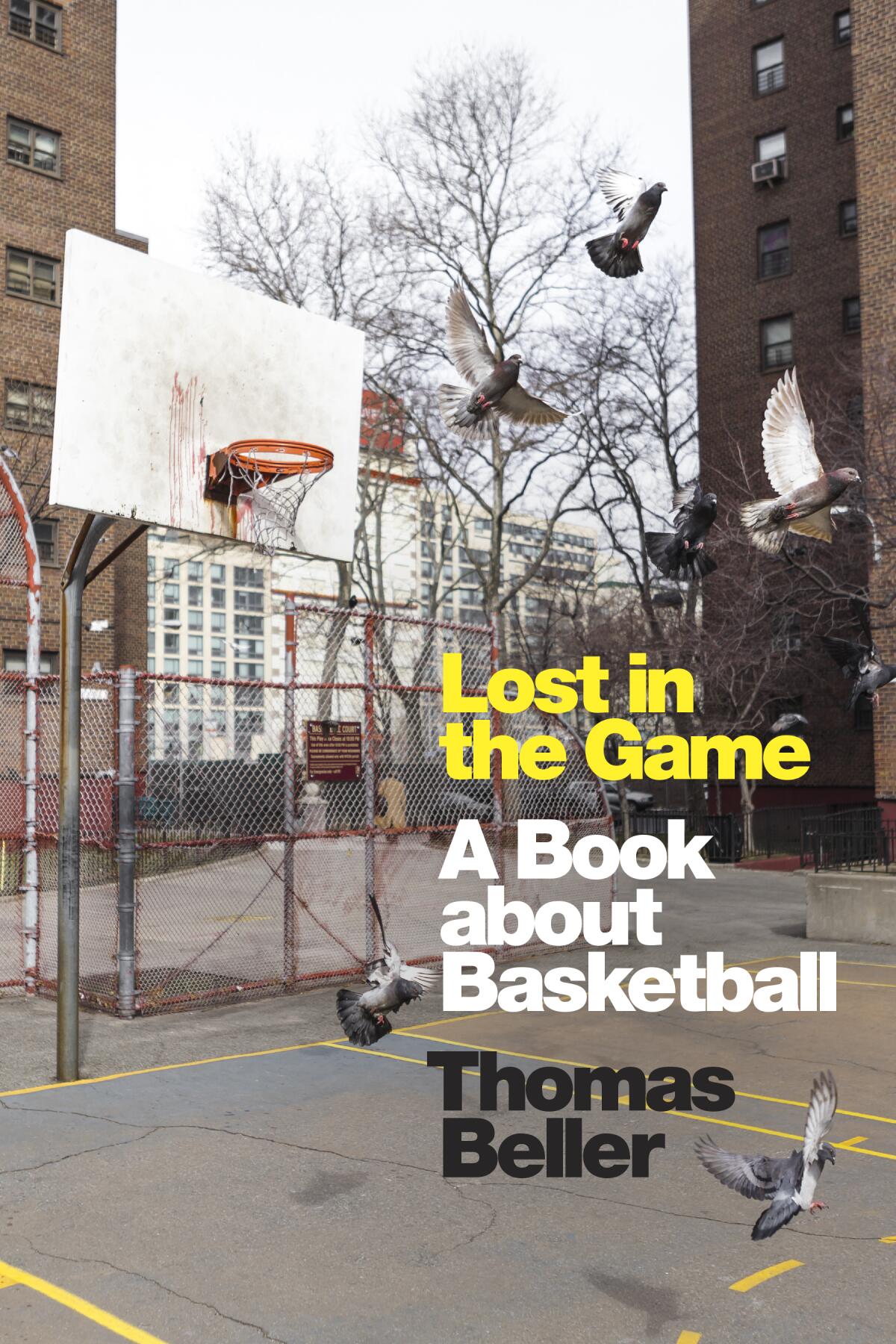

Not to mention timely. Beller will be in town this week to promote 2022’s “Lost In The Game: A Book About Basketball.” His fifth book is part memoir, part journalism and part essayistic exploration of the sport. His apology came via an email to my Times colleague, an acquaintance of his, and he linked to the piece I’d written, which he said he wanted to explain.

He’d been struggling, he said, after the sudden death of his close friend, Robert Bingham, when we met. Bingham had been publisher of the now-defunct Open City Magazine, which Beller had co-founded with Daniel Pinchbeck in 1990.

He was also still feeling the influence of the Gallagher brothers, he said. Beller had spent time with brothers Noel and Liam Gallagher of the band Oasis several years earlier while writing a memorable 1997 cover story for Spin magazine. In a role-reversed foreshadowing of my profile encounter, the mega-rock stars had given Beller all kinds of attitude while he, the young journalist, earnestly tried to report the story. But I digress.

Friend and author Thomas Beller recounts what made David Berman such a brilliant, beloved and ultimately fragile artist.

I was … surprised by Beller’s email. I was … a little bit touched. And I was … wary. How much of Beller’s apology was a play for book event publicity? While I don’t fault any author for being proactive about DIY publicity in these days of cash-strapped publishing, bundling it into a retroactive apology felt dubious.

“If she isn’t interested in such an act of gratitude — I want to say thank you for her general forbearance and equanimity,” Beller wrote in the apology email. Then: “Maybe she can mention the reading or the book on the arts page?”

No matter. I bought Beller’s book. I know next to nothing about basketball, but I love narrative nonfiction. What I thought I knew of him from our single, long-ago exchange didn’t come through in the writing, where Beller is both self-reflective and sharply observant, heartfelt and magnanimous.

I found myself softening to him with every turning page.

“Lost in the Game” is an illuminating and unexpectedly poignant collection of essays, traversing the worlds of both professional basketball and pickup games. Beller played basketball on teams from middle school through college and has covered the sport as a journalist. He writes intimately about it, but he also touches on the death of his father, when he was 9, and the subsequent search for father figures on the court. And he addresses being the father of a roughly 9-year-old son who is himself just discovering the joys of basketball.

Beller chronicles the courts — in Manhattan, in Paradise Valley, Mont., in a Phnom Penh parking lot — as well as dramatic moments from memorable games. A high point of the book is Beller’s use of the court as a canvas to depict myriad characters: legendary NBA players; a man he caught sight of while in a cab at a stoplight, rhythmically shooting hoops alone around midnight; the many players he commingled and connected with over the decades on patches of asphalt in pickup games, knowing little more than their nicknames and playing styles. Guys like Birdie and Puppet and Tweety and Red.

In the book, Beller describes basketballs repeatedly whooshing through hoops as a sort of “continuous waterfall of motion” — flowing throughout a single game, but also in memory. I related: His email had unleashed a waterfall of memories. Since he’d gotten in touch, I’d plummeted into a nostalgic black hole of concentric decades.

In a bizarre twist, the week of Beller’s apology, I’d interviewed Bangles frontwoman Susanna Hoffs onstage at the L.A. Times Festival of Books, after which she performed a contemporary, acoustic version of “Manic Monday.” I’d rarely heard that song over the decades. Listening to her 2023 version of the ’80s hit at the festival sent me back to Beller and the year 2000.

Bangles singer Susanna Hoffs has written a novel, ‘This Bird Has Flown,’ about an ‘over-the-hill’ one-hit wonder finding love — and it kind of rocks.

More than anything, Beller’s email had left me melancholic.

So much from that memorable afternoon was now gone. The LA Weekly — the influential cultural heavyweight that it was, at least — was no longer. The Hollywood Hills Coffee Shop where we’d met, was no longer. Open City had folded. Oasis had broken up. My marriage was a distant memory. My younger creative self, which had long ago set out to write literary nonfiction not unlike Beller’s, had morphed. Re-reading my piece, I barely recognized that calcified version of my inner voice.

There’s nothing particularly surprising about the fact that things change and disappear over time. But Beller’s email, and the link to my decades-old story, brought a lot rushing back at once.

I was curious why Beller had dug up our interview in the first place. Why apologize now? So I reached out and we chatted by phone. It turns out he too had been afflicted by nostalgia, though his came on a few years earlier. In late 2017, when LA Weekly laid off nearly 70% of its editorial staff, Beller Googled around for more information about the paper’s “death seizure,” as he calls it. He unearthed our interview.

“I felt so mortified and sad for both of us in a way,” Beller said. “I was like, oh my God. It’s one thing to be cheeky, but this is so kind of rude. Here’s this nice young woman who cares about something you wrote, has responded to it. Could you be more self destructive?”

Planning this week’s visit to a city he’s traversed using the LA Weekly as a guide, he says, sparked thoughts about the shrinking alternative media and about our interview, which he re-read. Which itself sparked thoughts about his own creative trajectory — it put him in touch with the fiction writer he was before he pivoted to nonfiction.

“And I just knew enough that I felt that I should apologize to you,” he says. “That it was an errand that I should do. Make it right.”

Was it entirely without a personal agenda? That gets down to “issues of purity of intent,” Beller says.

“This used to flutter around in my head a lot with Open City. If you’re publishing a literary magazine, it’s both. You’re doing this amazing thing for the culture and you’re patronizing, in the good sense of that word, writers — helping them and being really generous. And you’re making a name for yourself.”

Jeff Benedict’s LeBron James biography isn’t just great sportswriting, it’s also vivid narrative journalism.

The same was true of his email, he admits.

“There’s both a self-interested element and this very kind of lovely generous element. And I’m kind of in favor of acknowledging that those things coexist in people.”

The other thing that evaporates with time? Grudges. I remained engrossed in Beller’s basketball book long after finishing this piece. As with any really good book, the reader forms an intimate connection with the writer, carrying that literary voice around on errands, in the car, to the grocery store. I thought of scrapping this piece; with every passing essay of his, I thought of Beller more and more as a close friend.

After our phone conversation, I thought of Beller as — if not as a friend, then a friendly contemporary.

I have no idea who he really is, or who he really was back in 2000, for that matter. But one thing is certain: He is a wonderful writer.

Beller will discuss “Lost in the Game” with Cathleen Schine at Diesel on May 11 at 6:30 p.m. Check it out.

And as for his apology: I accept.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.