Commentary: What the Hollywood Bowl’s complicated history reveals about Los Angeles

- Share via

On what was likely a hot and humid summer day in Chicago, Percy Grainger hailed a taxi. The year was 1928, and the famed composer and pianist was leaving for Los Angeles to conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl and for his wedding.

Grainger deposited his luggage in the trunk of the car and, as was his wont, this most eccentric of all major composers jogged alongside the taxi to the train station.

His fiancé, Ella Viola Strom, a Swedish poet and actress who knew nothing of L.A., arrived separately from Australia for what she imagined would be a quaint outdoor ceremony among a few of Grainger’s friends and colleagues at a nice Hollywood picnic spot. In fact, Grainger had arranged for a Swedish Lutheran pastor to marry them on the Bowl stage during his concert, and she is said to have nearly fainted when she walked out and saw an audience estimated at 25,000. Grainger prepped the crowd conducting the premiere of his “To a Nordic Princess,” a contentedly rambling, erotic “bridal song.”

This was the sixth season of the L.A. Phil’s “Symphonies under the Stars,” and Grainger devised a flabbergastingly varied, contemporary, personal, showy yet serious, inventive and inclusive program. There was the “Nordic” Symphony by the up-and-coming American composer Howard Hanson, and Rubin Goldmark’s “A Negro Rhapsody,” both written as recently as 1922.

Grainger further introduced Fannie Dillon’s “In a Mission Garden.” The trailblazing Los Angeles composer and reputedly sensational pianist, who taught at Los Angeles High School and liked to incorporate birdsong and Native American chants into her pieces, is now little remembered. In those enlightened days, she was among the guests of honor at the celebratory wedding dinner at the Hollywood Plaza Hotel, where the happy couple was surrounded by movie stars and classical music luminaries.

There have been countless notable Hollywood Bowl events and their storied Hollywood aftermaths. But Grainger’s wedding night, which outraged some for its audacity and vulgarity and delighted others for its sheer chutzpah and exceptional music-making, is the Hollywood Bowl in a nutshell.

The Hollywood Bowl represents L.A. in all its naked splendor, idealism, commercialism, diversity, communal aspirations toward equality, social division, tackiness and even sordidness. It has been, for its full 101 years, the best of us and, if maybe not the worst, the not-so-hot of us. It is progressive L.A. and backward L.A. It is L.A. as embracer of the unconventional and L.A. as exploiter of the conventional.

The Hollywood Bowl is celebrating its centennial. Learn about its history with the L.A. Philharmonic and the Beatles, Janis Joplin and more.

Like all great creation myths, the Bowl’s was a mystical birth surrounded by mystery. Who discovered that Daisy Dell, just off Cahuenga Pass, would be a natural acoustic miracle? The ultra-modernist émigré French composer, eminent astrologer and silent film actor (Christ in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 “The Ten Commandments”) Dane Rudhyar told me it was he.

Rudhyar had come to L.A. to write music for a monumental outdoor spectacle on the life of Christ to be mounted in the Hollywood Hills. In 1918, Christine Wetherill Stevenson, a wealthy heiress from Philadelphia who was a member of the Los Angeles Theosophical Society — that spiritual admixture of Eastern religion, Platonic philosophy and occult — had built an amphitheater at the top of Argyle to stage Light of Asia” about Buddha and drew large crowds. She now wanted to go all out for Jesus.

Although Rudhyar claimed he was the first to scout the little valley off Highland Avenue for Stevenson’s pageant, official sources credit a young actor and his father with accidentally recognizing a natural acoustical basin. Musical tryouts reportedly began as early as 1919 in the Dell. But my guess is that Rudhyar was the first professional to recognize the real potential of the site and the one to persuade Stevenson to purchase the property before developers got their hands on it.

The composer described it as a miraculous setting that little by little, over the years, wound up being completely destroyed by developers. Listen to any of Rudhyar’s exceedingly strange music and you know he had an ear.

What came next was a mess. As Catherine Parsons Smith puts it in her authoritative history, “Making Music in Los Angeles,” the contestants for the Bowl’s beginnings “both male and female but mainly middle-to upper-class, included proponents of theater and champions of music; real estate developers and promoters of public parks; theosophists and agnostics, all in a kaleidoscope of unexpected, and unexpectedly shifting alliances.”

The upshot was that the creation of the Bowl as we know it was a battle in its first decade between principled, imaginative women and some men who were not. The result has been a century of unexpectedly shifting associations between aspirations of classical arts and popular entertainment.

The differences were spelled out from the start, when Stevenson ultimately created the Pilgrimage Theater across Highland in 1920 for her exalted concept of art and theater and spirituality, while another missionary woman and friend of Stevenson, Artie Mason Carter, turned the Dell into the Bowl.

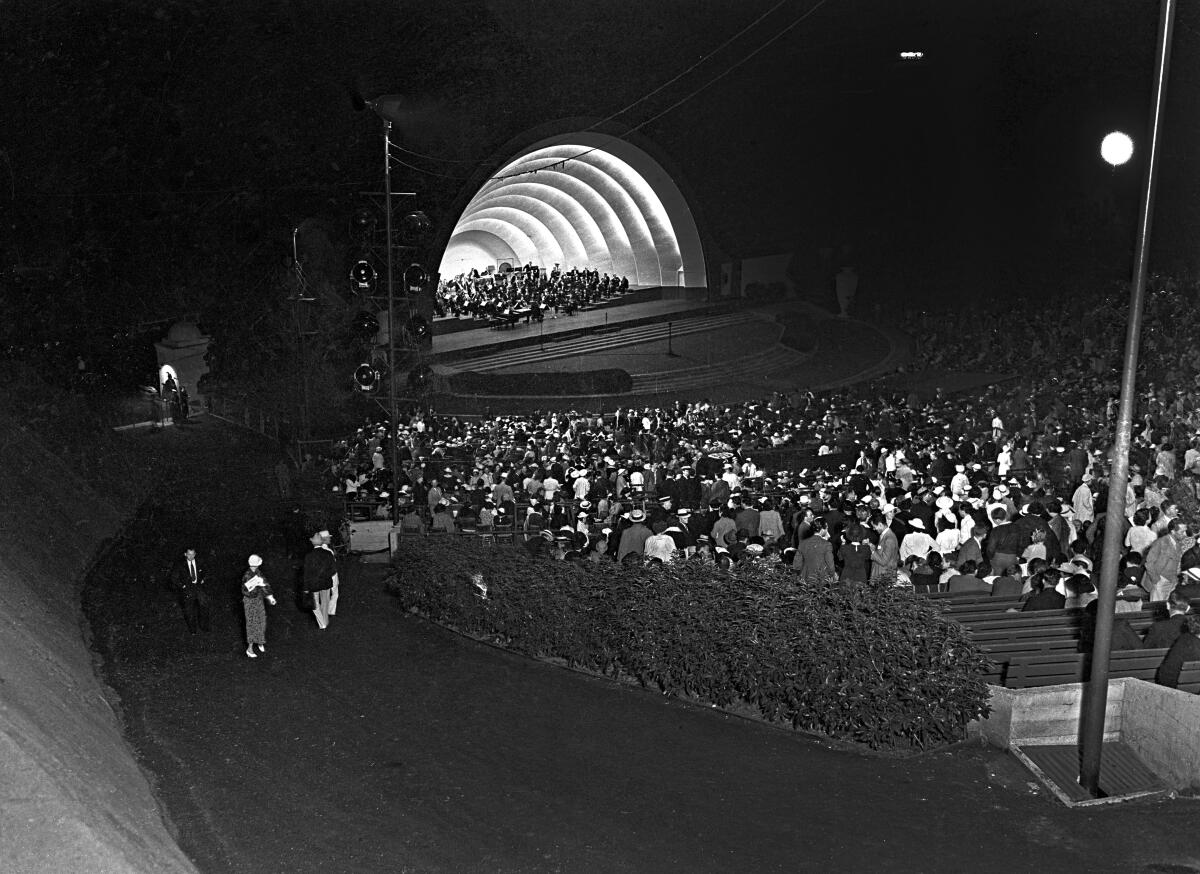

As the first president of the Hollywood Bowl Assn., Carter created a summer home for the new Los Angeles Philharmonic on Cahuenga Pass, where motley musical and theatrical performances were staged before a shell was installed, and where Easter sunrise services began in 1921. Her purpose over the next few years as the Bowl became a quick success was, in her words, to “keep the Hollywood Bowl democratic” in the face of a Bowl board’s “policy of money grubbing.”

Carter — whose roots were in participatory community singing and who produced an open-air sing at the nascent Bowl in 1920 that attracted a crowd of 2,000 — believed in the amphitheater as a place where tickets could cost as little as a quarter and that would be welcoming enough to make great art available to and representative of all. She strove to bring people together, despite such obstacles as a Hollywood when Black people were not welcome on the street after dark.

Most of all, Carter tapped into a revolutionary new decade in musical accessibility. Radio and recordings had begun to spread the word (and sound) big time. Popular music books became bestsellers, producing what composer and critic Virgil Thomson dubbed “the music education racket.” Meanwhile, old-school stalwarts fought back. The first L.A. Phil music director, Walter Henry Rothwell, refused to make music “out of doors,” where too much of music’s essence would presumably be lost to the environment.

Carter turned instead to the San Francisco Symphony’s distinguished, avuncular German music director, Alfred Hertz. Dubious at first but an eager advocate of America creating its own musical culture, Hertz gave the idea of “Symphony Under the Stars” a whirl. The first symphony concert was July 11, 1922. The rest is history.

Hertz was instantly popular. He loved reaching the masses. “I believe that I have done more to spread the gospel of good music during the last 10 weeks,” he proclaimed, “than in all my life.” In 1935, the New York Times took notice when its imperious music critic, Olin Downes, visited and found himself enchanted, saying that he discovered at the Bowl a “flavor different from any other concert known to me.”

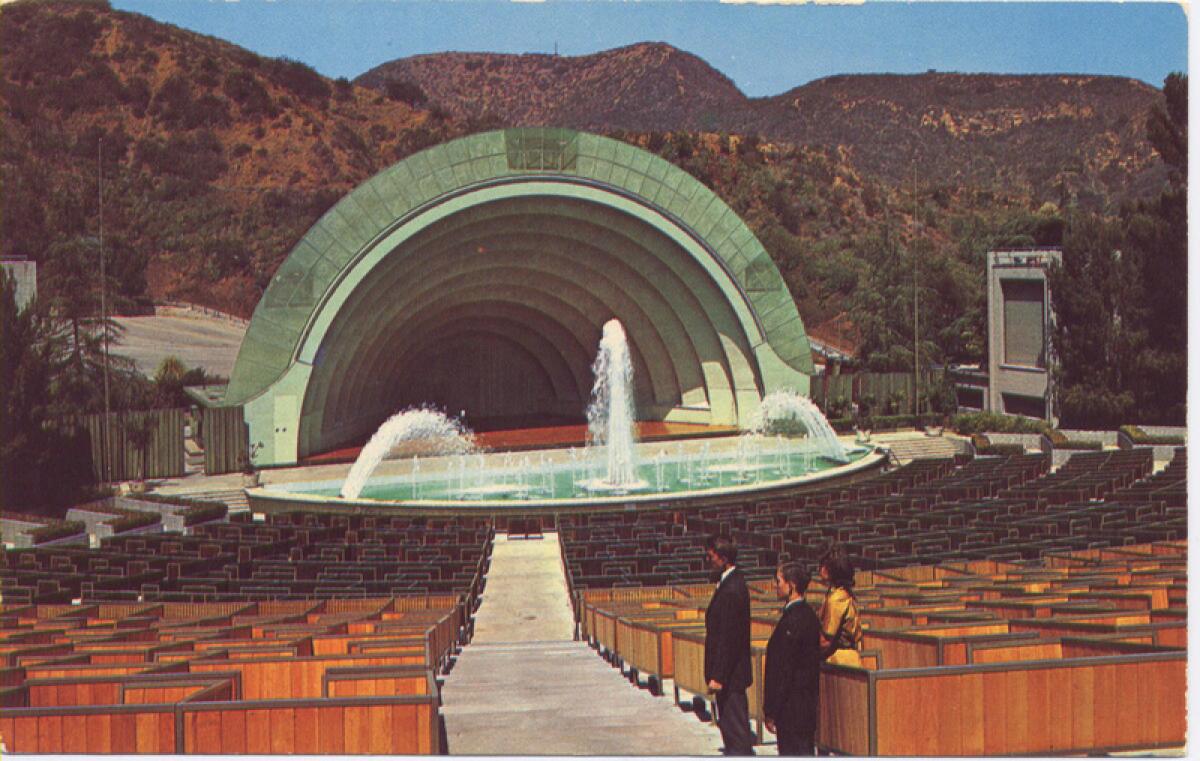

With its special acoustics and lovely atmosphere, the Bowl quickly caught on as a place for concerts and spectacles where operas and ballets and other kinds of events could be staged. Strikingly new and different portable orchestra shells (that could be removed for theatrical events) went up in the first years, and the seating increased to 20,000 (although crowds up to 25,000 squeezed in, as they did for Grainger). Carter proved that “art music for the people at popular prices” could pay for itself, all of which led to what became known as the battle of businessmen versus democratic dreamers.

In 1926, Carter lost her battle against the board when it insisted upon building 400 boxes for deluxe seating and installing a fancier shell, the first in a series of “improvements” that would over the years alter the natural acoustic. Big money won out with Carter described as “NOT a businesswoman but a crusader with the zeal of a fanatic,” who was “up to her pretty ears” in her crusade.

It is impossible, at our remove, to assess what damage the construction or management changes did. The first L.A. Phil recording was made at the Bowl in 1928, three weeks after Grainger’s extraordinary appearances, when a team from RCA Victor arrived with newly invented portable recording equipment and held early-morning recording sessions on the Bowl stage.

The conductor for the recordings was Eugene Goossens, the European maestro who came to town to lead the L.A. premiere of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” at the Bowl. The L.A. Phil has just released a seven-LP set of Hollywood Bowl highlights that begins with the first of those 78 rpm recordings from 1928: Dvorak’s “Carnival” Overture. It is a terrific performance, full of spunk. Although it was released on an excellently remastered and invaluable CD by Cambria Master Recordings in 2004, the recording has a particularly lovely aural ambience on vinyl. There was no way with 1928 technology to make this wonderful recording had it been in a poor acoustic, with a poor orchestra giving a poor performance. This, then, remains the best evidence we have of how and why the Bowl worked.

The Bowl isn’t a bad place for tracing the changes in music and society, in a distinctly L.A. way, over the next decades. The first woman to conduct the all-male L.A. Phil (and maybe any other major orchestra) was composer and pianist Ethel Leginska in 1925. In 1927, the year architect Lloyd Wright designed a pyramidal modern shell for the Bowl, Native Americans held intertribal ceremonials in the venue. In 1936, composer William Grant Still became the first Black person to conduct a major American orchestra when he performed two of his works with the L.A. Phil at the Bowl.

Dreamers somehow still dreamed. In 1933, the L.A. Phil amazingly engaged the iconoclastic Russian-born conductor Nicolas Slonimsky to lead a summer of avant-garde music. Slonimsky wrote in his autobiography that “moneyed dowagers” called him a “dangerous musical revolutionary who inflicted hideous noise on concert-goers expecting to hear beautiful music” and insisted he be given the boot or they would cease funding the Bowl.

The dowagers got their way but not before a 20-year-old former piano student of Fannie Dillon‘s at UCLA heard Slonimsky conduct the West Coast premiere of Edgar Varèse’s new “Ionisation,” the first important Western concert work for percussion ensemble. John Cage, who had graduated and spoken on the Bowl stage that spring, later attributed this revelatory performance as his first step instigating a legendary percussion revolution that altered the course of 20th century music.

In enticing Hollywood celebrities, ostentatious high-society picnicking as well the hoi polloi ($1 seats became one of the Bowl’s wondrously lasting traditions), along with attracting worldwide listeners through radio broadcasts and recordings, Slonimsky’s experiment only served to confirm to L.A. Phil administrators that the venue needed to attend to popular tastes. But the bigness of the venue and broadness of the audience had the advantage of also stimulating vast quantities of adrenaline from the world’s greatest stars.

The handful of broadcasts graduated, and spoken-of dazzling performances that have made their way onto disc, download or YouTube include Vladimir Horowitz’s electrifying Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3, “Madama Butterfly” conducted by Eugene Ormandy and other great, great performances from the likes of Isaac Stern, Jascha Heifetz, Toscha Seidel, Mischa Elman, Oscar Levant, Duke Ellington, Serge Koussevitzky, Leon Fleisher, Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter and Leopold Stokowski.

On the other hand, recordings conducted by Felix Slatkin and Carmen Dragon with romantic “Starlight Concerts” LP jacket art made the Bowl synonymous in the popular imagination with light classics. Nor was the entrance of smooth jazz and pop in the 1930s and 1940s itself so smooth. The headline for The Times review of Benny Goodman’s Bowl debut in 1937, its first jazz concert, was “Goodman’s Killer-Dillers Go Whacky in the Bowl.”

Frank Sinatra’s debut in 1943 caused greater dismay. Under the headline, “Cash to be Crooned Into Coffers of the Bowl,” the normally open-minded and even-handed Times music critic Isabel Morse Jones (who had been the first publicist of the Bowl before joining the paper in 1925) complained of the crooner producing “an opium of emotionalism.” Jones didn’t complain much longer.

Dorothy Buffum Chandler, wife of The Times’ publisher, realized, however, that crooned cash wasn’t enough to keep the Bowl afloat. In the early years after World War II, the Bowl had become bland and began losing popularity. Chandler removed Jones and took it upon herself to prevent the Bowl from falling into bankruptcy.

The ballyhooed acoustics of the Bowl had already become less impressive in the 1930s and early 1940s. Stokowski, who formed the first iteration of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, experimented with amplification systems — boys with their toys, Jones felt. Construction of the Hollywood Freeway, which required leveling a hillside and thus removing a crucial reflector of sound, was the last straw.

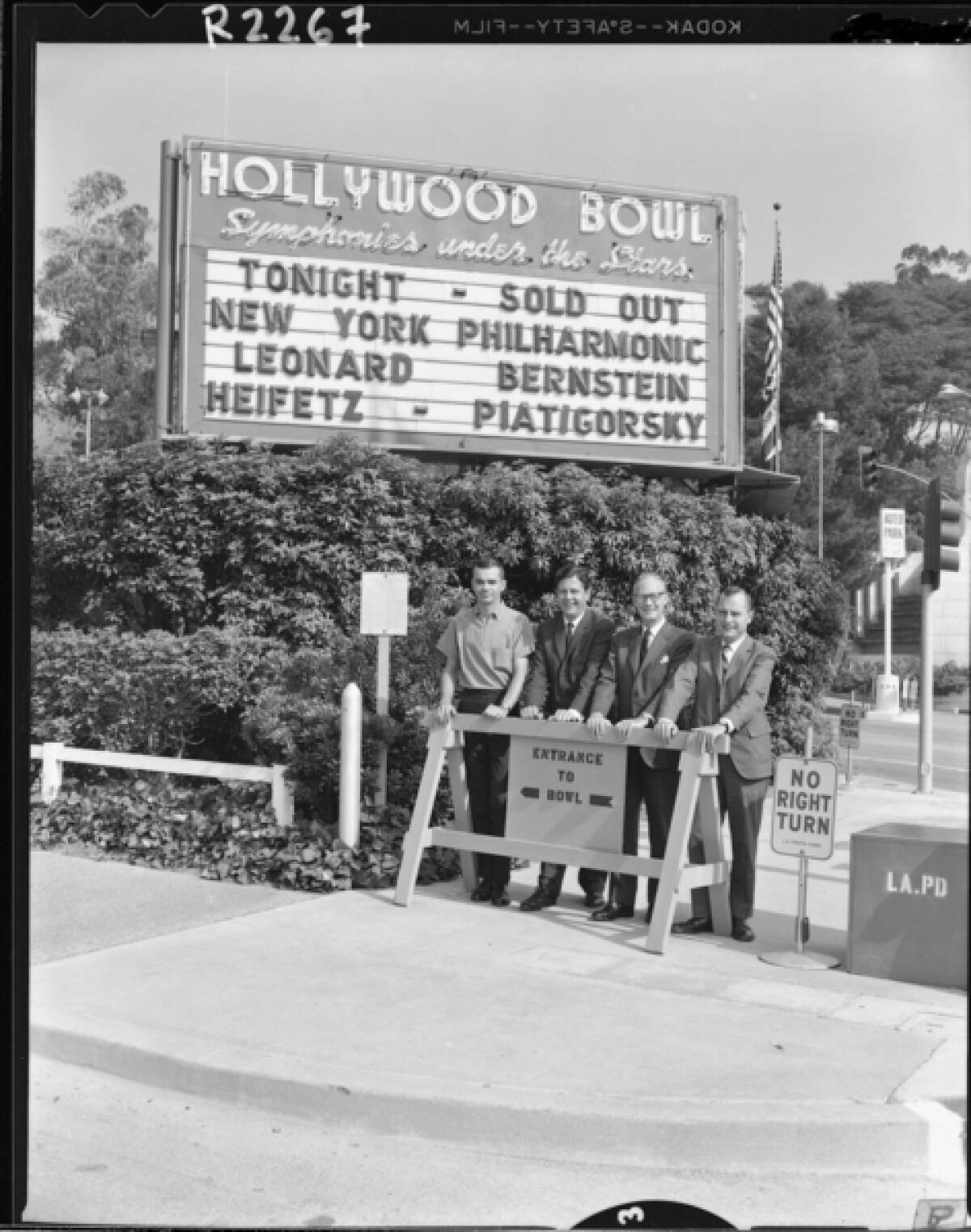

Chandler, who also took over running the L.A. Phil, led a fundraising campaign that saved the Bowl, which then gave her the impetus to then build the Music Center downtown. In the process, the Bowl turned more mainstream than ever in the 1950s. There were, though, notable exceptions, in particular the 1955 Festival of the Americas, which Leonard Bernstein, who had begun working on “West Side Story,” curated and conducted. He invited Billie Holiday, Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, Dave Brubeck, then film composer and jazz pianist André Previn, as well as jazz drummer Shelly Manne.

That festival was my introduction to the Bowl as a child. I had seen Bernstein on television but was too young to remember much. What sticks in my memory is that my mother brought her mink stole, as ladies did then for chilly summer nights. And my three-pack-a-day father made sure he had a book of matches for me. At the end of intermission, all the lights were turned off and everyone lit a match. Wow!

That began my own love/hate relationship with the Bowl, something shared by nearly all local critics with the exception of the late Alan Rich, his box at the Bowl the only place on Earth where a bad performance wouldn’t make him grumpy. For three decades, my predecessor at The Times, Martin Bernheimer, belittled the Bowl, saying we shouldn’t review picnics, and studiously reported the number of wine bottles that noisily rolled down the aisles and aircraft that noisily flew overhead during performances.

When I flocked to the Bowl in high school with friends, we bought dollar seats and moved down to the boxes (easy in those less uptight days), where I excitedly heard my first big Mahler performances. I pooh-poohed the Bowl in college until the flamboyantly visionary executive director of the L.A. Phil, Ernest Fleischmann, started doing adventurous marathons of new music and Beethoven.

When I began reviewing the Bowl in 1976, the amphitheater was more often than not in the doldrums. Classical concerts during the week and pop (more schlock than not) were kept apart. Various attempts were made to improve acoustics and beef up amplification. The average L.A. Phil concert was, and still is, barely rehearsed, getting two hours the morning of the concert (which is open to the public). Young artists were regularly invited to make their debuts with the orchestra through trial by fire.

There could always be magic, of course, but the truth is that over the years L.A. Phil music directors tended to be like Rothwell and needed arm-twisting to conduct at the Bowl (even Rothwell gave in, and he conducted once in 1925). Finances always mattered, particularly once Fleischmann discovered how effectively the Bowlcould finance an ambitious winter concert season. Even so, dreamers dreamed (Peter Sellars was lured to produce L.A. Phil concerts with Esa-Pekka Salonen at the Bowl in the 1990s). The finding of common ground between pop and classical began to seem more plausible with the advent of Zubin Mehta’s “Star Wars” concert in 1977 and the growing popularity of John Williams’ music.

The Hollywood Bowl of the 21st century remains a work in progress. The installation of a cavernous new shell in 2004, a stupefying magnification of the iconic old one, with an artificially powerful sound system and giant video screens, seemed to spell the end of any intimacy the Bowl might have still maintained. When Randy Newman was overheard quipping, “I don’t come to the Hollywood Bowl to watch television,” he took the words out of many of our mouths.

Rather than focus attention, the bigness of the video and amplification seemed to accomplish just the opposite: inviting more distraction. When young conductors made their antsy debuts, they faced intense video scrutiny.

For the record:

4:45 p.m. June 6, 2022An earlier version of this articled stated that Gustavo Dudamel won a conducting competition in Hamburg, Germany. It was in Bamberg.

The next summer, one such 24-year-old who was the first winner in a new conducting competition in Bamberg, Germany, made his U.S. debut at the Bowl. The annoying picnickers in the box next to me put their Doritos down once the concert began and didn’t touch them again until intermission. Gustavo Dudamel, like no conductor I had witnessed before him, instantly embraced the Bowl, holding both orchestra and the large crowd in the palm of his conducting hands.

After 18 years, the Bowl has become the Dudamel era. With a musician like this, the facility had no choice but to get better. With him on the podium, video became an advantage. The sound received regular upgrades until it became compelling. Last summer, the Bowl achieved, under Dudamel, the greatness it had advertised for a century.

Times, of course, change. For all the Bowl’s artistic barrier-breaking, the separation of popular culture and classical arts has never seemed greater, with pop culture now getting the lion’s share of attention and becoming the art form of both big business and the ruling class. Andrea Bocelli, who positions himself as having one foot in opera and the other in pop, brings no democracy to the Bowl by charging unconscionable ticket prices for his June 16 concert. Last I looked on the Bowl website, a seat in what would be the dollar section for L.A. Phil concerts is more than $200. A nice pair in the pool circle goes for nearly $15,000, including $2,361.98 in unspecified fees.

But while such economic inequality may remind us that business versus dreamers remains more than ever the way of the world, it also serves to put in perspective just how much Dudamel’s dreams have accomplished. Bocelli is a one-off, a Bowl rental that one hopes will be a crooner filling the county’s coffers. For all its problems (why no metro stop, for one?), the Bowl on a good night feels closer to its original democratic model than it has almost any time in my long history with it. You can’t say that about too many other institutions these days.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.