All these years later, however, I believe Valdes was right to want a movie made about Aldape, who was just 20 years old when he was sentenced to death in 1982 — even though the physical evidence showed that another man had fatally shot the police officer.

He became a folk hero for Mexicans who felt that immigrants face injustice in the United States. Ballads were written about his case and blared across the airwaves on both sides of the border. Hundreds of protesters blocked an international bridge to call attention to his plight.

As Aldape languished on death row, his case was taken on pro bono by attorney Scott J. Atlas, who led a team that uncovered how Houston police and prosecutors had intimidated and coerced multiple witnesses, many of them teenagers, into providing false statements that Aldape was the killer.

Prosecutors also had played to anti-immigrant hostility, telling jurors they could consider Aldape’s undocumented status to determine whether he would be a future threat to society.

In April 1997, after spending nearly all his adult life on death row, Aldape was released and walked off a plane with Atlas in his hometown of Monterrey, where they were swarmed by boisterous crowds.

He landed a role in a Mexican telenovela called “Al Norte del Corazón,” or “North of the Heart,” playing himself in the soap opera about Mexican immigrants abused by U.S. authorities.

Four months after becoming a free man, the 35-year-old Aldape slammed his Volkswagen into another vehicle. He died of his injuries.

Valdes had optioned the rights to a manuscript written by Atlas and another attorney who helped Aldape win his freedom.

“It was a good story,” Valdes recalled in a recent interview. “It was such a blatant example of railroading an immigrant who came to pursue the American dream and it became this American nightmare.”

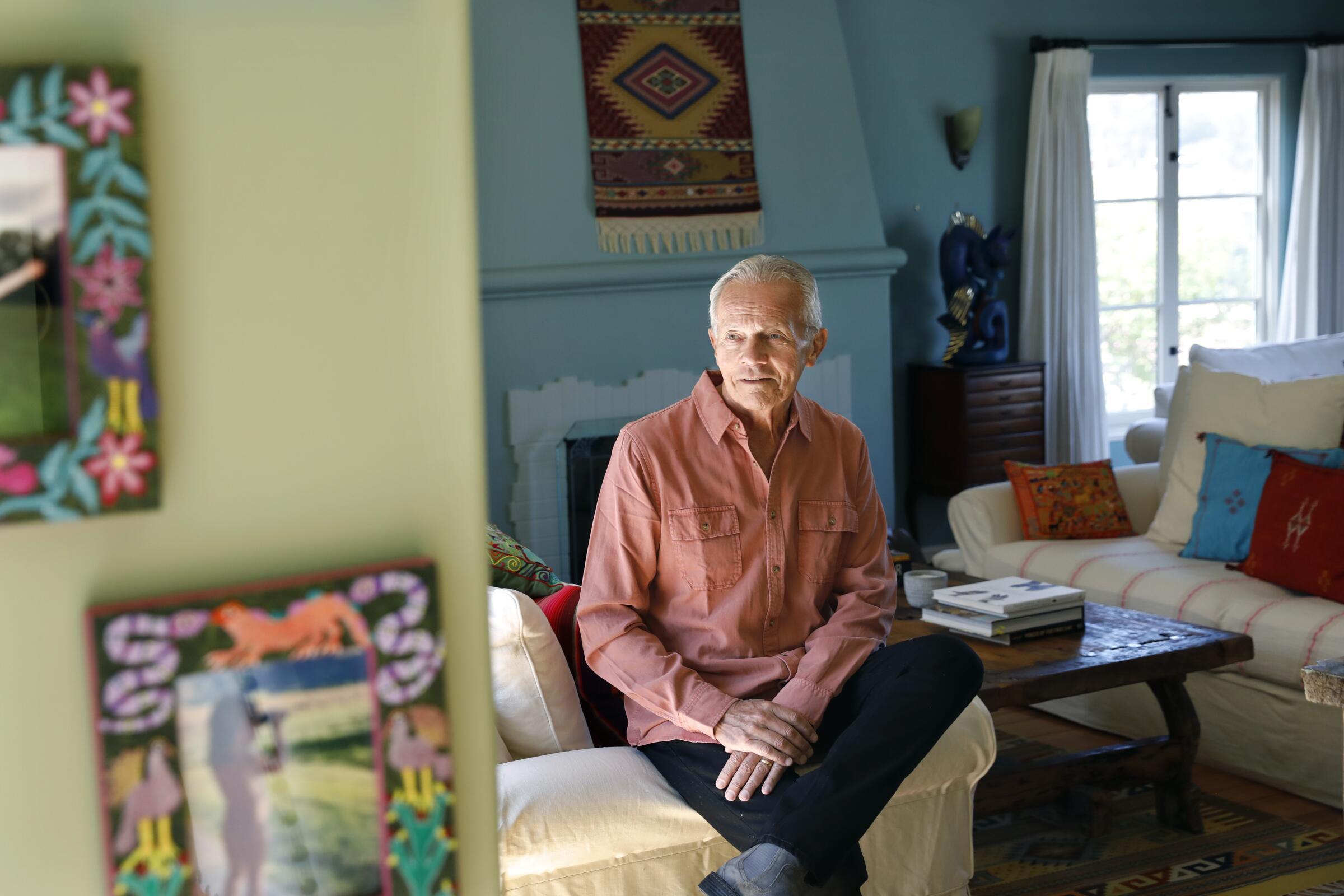

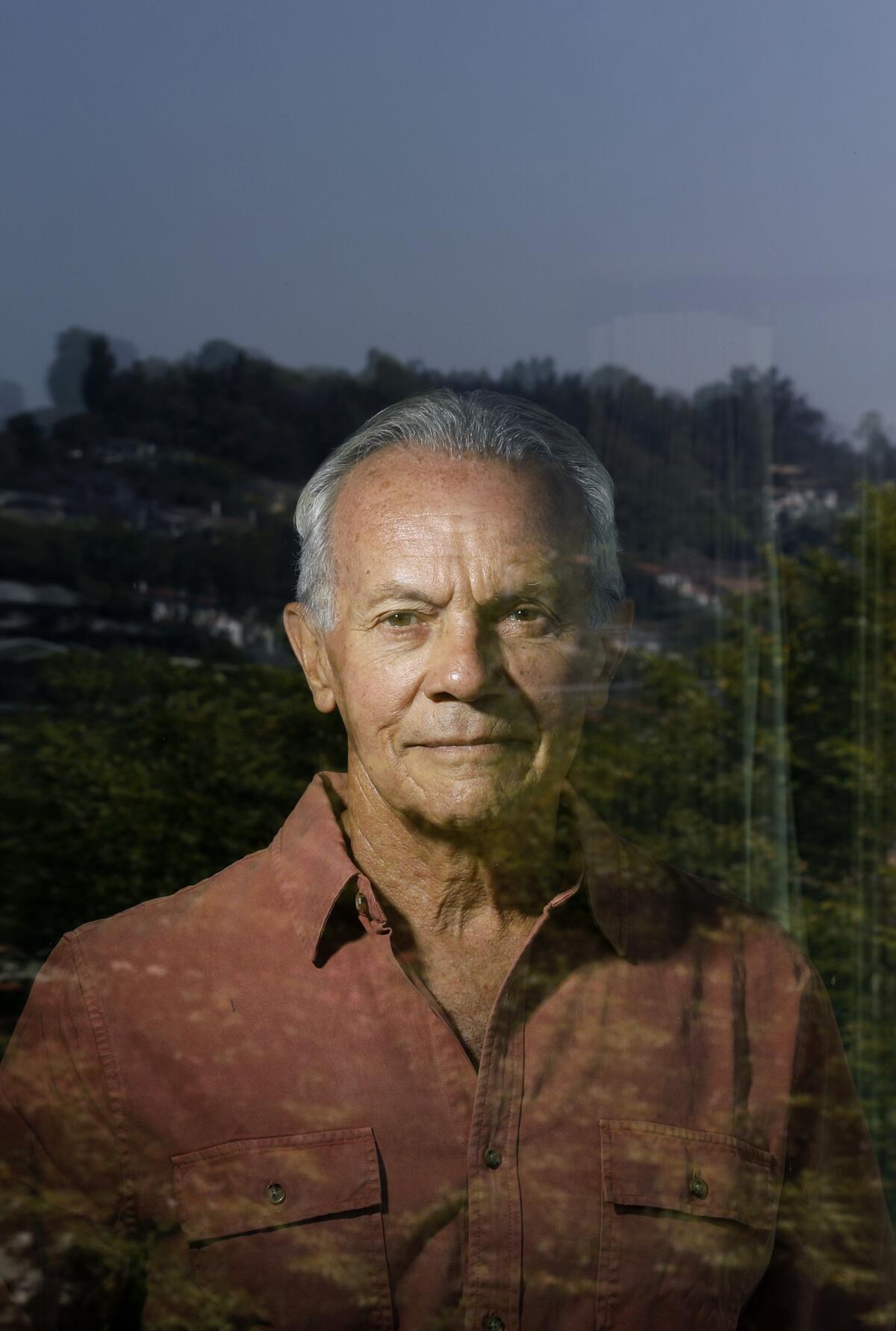

At the time, Valdes, who began his Hollywood career as a production assistant, had worked on more than a dozen films with Clint Eastwood, including “Bird” and “Unforgiven,” and had collaborated with noted filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese.

For Valdes, the project was an opportunity to produce a bilingual film that he believed would have wide appeal with audiences in English and Spanish.

But the script, he said, “required a detective approach, doing a lot of sleuthing and finding the facts and weaving that into a tapestry.” Or, perhaps a reporter.

Valdes read scripts and considered writers for the project, but he wasn’t satisfied — which may be why, when my screenplay arrived in his mailbox, he took a chance on me even though I had no formal training in screenplay writing.

I signed a contract with Valdes’ film company, Summer Magic Productions, and began poring over several boxes of court records and other files Valdes provided. I traveled to Houston and Monterrey, where I interviewed Aldape’s family.

During meetings at Jerry’s Famous Deli in Westwood, Valdes and I discussed revisions to the drafts I was writing. Valdes pitched the story to executives he knew at Telemundo, who were interested, but the cost of producing the film at the time — about $4 million or $5 million — might have been beyond the budget of the Spanish-language network, Valdes said. He also talked to executives at Searchlight Pictures, Focus Features and HBO.

“I went to all the usual suspects,” Valdes said. “Maybe I was naive in believing that the networks and the studios would have to acknowledge the bilingual and Spanish-speaking audience.”

Some executives viewed the project within the narrow confines of an “immigrant story” and failed to fully appreciate the larger themes, Valdes said. Others wanted to know whether any top talent was attached to the project. Valdes was considering Mexican directors and Spanish-speaking actors to portray Aldape.

“You can’t hire Tom Hanks or Brad Pitt to play Ricardo Aldape,” he said.