Screen misrepresentation of Mexicans isn’t just a longstanding wrong; it’s an original sin. And it has an unsurprising Adam: D.W. Griffith.

He’s most infamous for reawakening the Ku Klux Klan with his 1915 epic “The Birth of a Nation.” Far less examined is how Griffith’s earliest works also helped give American filmmakers a language with which to typecast Mexicans.

Two of his first six films were so-called “greaser” movies, one-reelers where Mexican Americans were racialized as inherently criminal and played by white people (a third flick replaced Mexican bandits with Spanish ones). His 1908 effort “The Greaser’s Gauntlet” is the earliest film to use the slur in its title. Griffith filmed at least eight greaser movies on the East Coast before heading to Southern California in early 1910 for better weather.

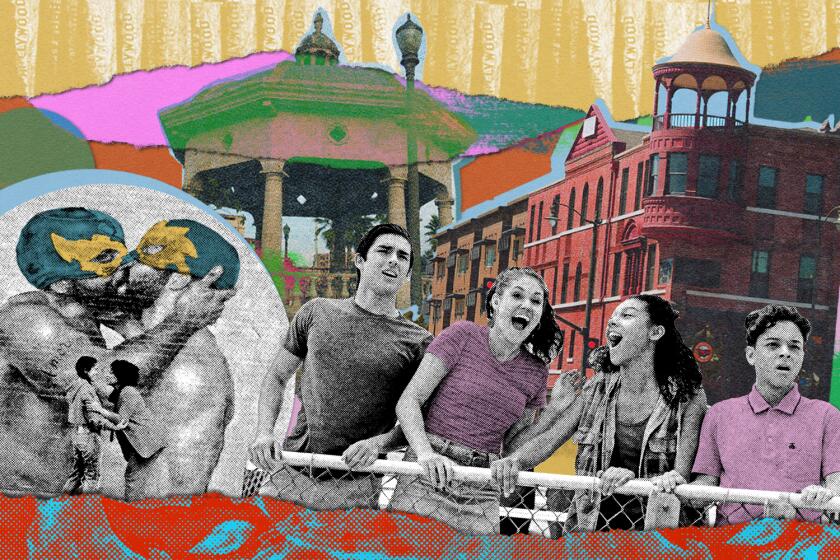

The new setting allowed Griffith to double down on his Mexican obsession. He used the San Gabriel and San Juan Capistrano missions as backdrops for melodramas embossed with the Spanish Fantasy Heritage, the white California myth that romanticized the state’s Mexican past even as it discriminated against the Mexicans of the present.

In films such as his 1910 shorts “The Thread of Destiny,” “In Old California” (the first movie shot in what would become Hollywood) and “The Two Brothers,” Griffith codified cinematic Mexican characters and themes that persist. The reprobate father. The saintly mother. The wayward son. The idea that Mexicans are forever doomed because they’re, well, Mexicans.

Griffith based his plots not on how modern-day Mexicans actually lived, but rather on how white people thought they did. This presumption nearly earned Griffith a beating from angry Latinos.

As described in Robert M. Henderson’s 1970 book “D.W. Griffith: The Years at Biograph,” the director was staging a religious procession in San Juan Capistrano for “The Two Brothers” when a large crowd “suddenly broke and rushed the actors” because they felt the scene mocked them. The company rushed to their hotel where the townspeople waited outside for hours. Only the intercession of the Spanish-speaking hotel owner stopped a certain riot. It was perhaps the earliest Latino protest against negative depictions of them on the big screen.

But the threat of angry Mexicans didn’t kill greaser movies. Griffith showed the box-office potential of the genre, and many American cinematic pioneers dabbled in them. Thomas Edison’s company shot some, as did its biggest rival, Vitagraph Studios. So did Mutual Film, an early home for Charlie Chaplin. Horror legend Lon Chaney played a greaser. The first western star, Broncho Billy Anderson, made a career out of besting them.

These films were so noxious that the Mexican government in 1922 banned studios that produced them from the country until they “retired... denigrating films from worldwide circulation,” according to a letter that Mexican President Álvaro Obregón wrote to his Secretariat of External Relations. The gambit worked: the greaser films ended. Screenwriters instead reimagined Mexicans as Latin lovers, Mexican spitfires, buffoons, peons, mere bandits and other negative stereotypes.

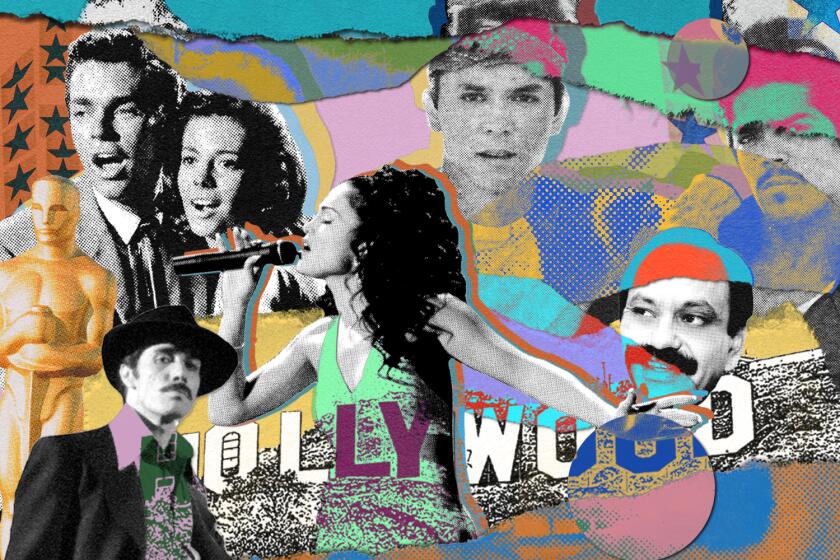

That’s why “Bordertown” surprised me when I finally saw it. The Warner Bros. movie, starring Paul Muni as an Eastside lawyer named Johnny Ramirez and Bette Davis as the temptress whom he spurns, was popular when released. Today, it’s almost impossible to see outside of a hard-to-find DVD and an occasional Muni marathon on Turner Classic Movies.

Based on a novel of the same name, it’s not the racist travesty many Chicano film scholars have made it out to be. Yes, Muni was a non-Mexican playing a Mexican. Johnny Ramirez had a fiery temper, a bad accent and repeatedly called his mother (played by Spanish actress Soledad Jiminez ) “mamacita,” who in turn calls him “Juanito.” The infamous, incredulous ending has Ramirez suddenly realizing the vacuity of his fast, fun life and returning to the Eastside “back where I belong ... with my own people.” And the film’s poster features a bug-eyed, sombrero-wearing Muni pawing a fetching Davis, even though Ramirez never made a move on Davis’ character or wore a sombrero.

These and other faux pas (like Ramirez’s friends singing “La Cucaracha” at a party) distract from a movie that didn’t try to mask the discrimination Mexicans faced in 1930s Los Angeles. Ramirez can’t find justice for his neighbor, who lost his produce truck after a drunk socialite on her way back from dinner at Las Golondrinas on Olvera Street smashed into it. That very socialite, whom Ramirez goes on to date (don’t ask), repeatedly calls him “Savage” as a term of endearment. When Ramirez tires of American bigotry and announces he’s moving south of the border to run a casino, a priest in brownface asks him to remain.

“For what?” Ramirez replies. “So those white little mugs who call themselves gentlemen and aristocrats can make a fool out of me?”

“Bordertown” sprung up from Warner Bros.’ Depression-era roster of social-problem films that served as a rough-edged alternative to the escapism offered by MGM, Disney and Paramount. But its makers committed the same error Griffith did: They fell back on tropes instead of talking to Mexicans right in front of them who might offer a better tale.

Just take the first shot of “Bordertown,” the one I inadvertently recreated on my television shoot.

Under a title that reads “Los Angeles … the Mexican Quarter,” viewers see Olvera Street’s plaza emptier than it should be. That’s because just four years earlier, immigration officials rounded up hundreds of individuals at that very spot. The move was part of a repatriation effort by the American government that saw them boot about a million Mexicans — citizens and not — from the United States during the 1930s.

Following that opening shot is a brief glimpse of a theater marquee that advertises a Mexican music trio called Los Madrugadores (“The Early Risers”). They were the most popular Spanish-language group in Southern California at the time, singing traditional corridos but also ballads about the struggles Mexicans faced in the United States. Lead singer Pedro J. González hosted a popular AM radio morning show heard as far away as Texas that mixed music and denunciations against racism.

By the time “Bordertown” was released in 1935, Gonzalez was in San Quentin, jailed by a false accusation of statutory rape pursued by an L.A. district attorney’s office happy to lock up a critic. He was freed in 1940 after the alleged victim recanted her confession, then summarily deported to Tijuana, where Gonzalez continued his career before returning to California in the 1970s.

Doesn’t Gonzalez and his times make a better movie than “Bordertown”? Warner Bros. could have offered a bold corrective to the image of Mexican Americans if they had just paid attention to their own footage! Instead, Gonzalez’s saga wouldn’t be told on film until a 1984 documentary and 1988 drama.

Both were shot in San Diego. Both received only limited screenings at theaters across the American Southwest and an airing on PBS before going on video. No streamer carries it.