Appreciation: Few ever heard Ennio Morriconeâs avant-garde music. Why it was key to his movies

Ennio Morricone, who died Monday at age 91, was, of course, famed as the outrageously prolific and inventive film composer of such classics as âThe Good, the Bad and the Ugly,â one of his more than 500 movie scores. His stylistic range covered everything from up-to-the-minute experimental to yesterdayâs most tired schlock, leading to the equally tired quip that his music was the good, the bad and the ugly.

Less appreciated, though, is how much the ugly helped make Morricone so good.

Besides his film music, Morricone wrote more than 150 concert works, which he considered absolute music, many avant-garde. There is a very good chance that youâve heard none of them. Live performances outside of Italy have been exceedingly rare, and nearly nonexistent in the U.S. Only a tiny fraction has been recorded. Yet Morricone insisted, the time I interviewed him, that it was far and away his most important work.

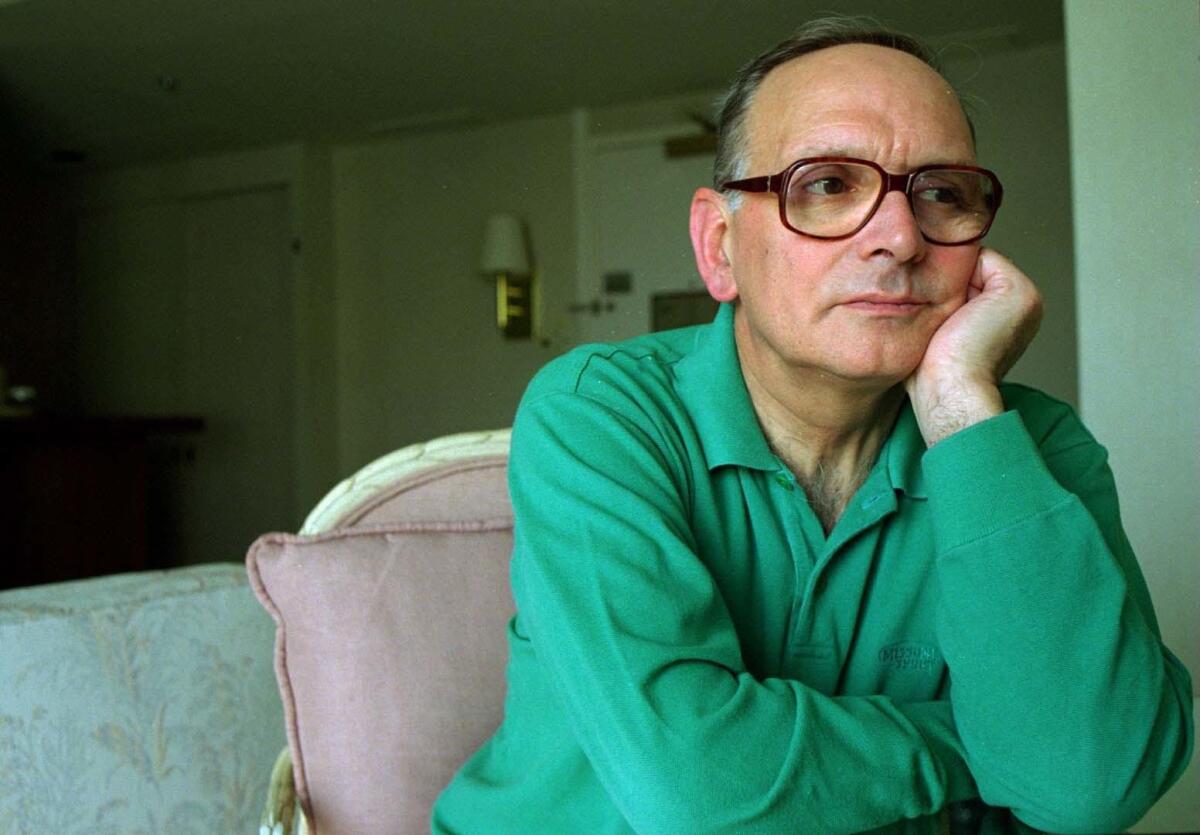

The only apparent reason Morricone â who hardly ever came to America, didnât speak English and had zero regard for music journalists â agreed to speak with me was because I said I wanted to focus on his âseriousâ music. Even so, the interview started badly when I asked the composer, a princely presence in his velvet slippers with embossed crowns, to describe his concert work, since I knew so little of it.

Before YouTube or streaming, before he had a website, before the music could be found on CD, the only way to encounter any of it was to attend the premiere in Italy. Morriconeâs undisguised impatience indicated that was no excuse. But when I mentioned that I had seen him perform as a member of Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza in Florence in the early 1970s and that I had bought all the ensembleâs albums when they came out, his demeanor changed. I was one of the clan.

The Group, as it was called on its first American LP, âThe Private Sea of Dreams,â in 1967, was a radical improvising collective formed by Italian composer Franco Evangelisti in 1964. Its heyday was in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Morricone played trumpet in it for a dozen years, and what I remember from the performance I attended was what a cool, formidable presence he had.

The timing was critical. Morriconeâs distinctive, multifaceted musical personality was just coming into being when he joined the Group. He had just scored Sergio Leoneâs âA Fistful of Dollarsâ (which made Morriconeâs name), Bernardo Bertolucciâs âBefore the Revolutionâ and John Hustonâs âThe Bible,â along with several cheesy Italian exploitation films. The Group, on the other hand, challenged some of the basic tenets of what most people think music should be, and it challenged everything film music is supposed to be.

In the early 1960s, Morricone had studied with Goffredo Petrassi, a respected mainstream modernist Italian composer with an outsize influence on a new generation. His students included such avid avant-gardists as the anarchistic Englishman Cornelius Cardew and the unpredictable Italian Franco Donatoni (with whom Esa-Pekka Salonen studied), as well as American composer and influential critic Eric Salzman.

Morricone joined right in, and by the late 1950s, he was adept at the latest experimental techniques of electronic music and, as he wrote in his memoir, âLife Notes,â had taken to heart John Cageâs insistence that âall real-world sounds ⌠belong to music.â He embraced noise and demonstrated a talent for finding things that instruments could do that no one else thought of. To earn his keep, however, he moonlighted playing trumpet in clubs and arranging pop recordings, mastering studio techniques in the process. When he started to blow for Evangelisti, Morricone said he was just coming to terms with living a double life as a composer, writing advanced âabsolute musicâ entirely on his terms and commercial music on someone elseâs. The Group offered a third way that made surprising sense to both worlds.

Ecstasy and excess, rhythm and repetition, gender and ethnicity. Lyricism, protest, healing. Critic Mark Swedâs series on the ideas embedded in every note.

In his musical revolution to save music from what he called the âalready done,â Evangelisti had come up with a novel systematic approach to improvisation. Every member had to be a composer and accomplished performer, but no individual player had priority. No sound produced could be bound to the tonal system. There could be no rhythmic periodicity or repetition, no easily remembered tunes (of which Morricone happened to be genius), no clichĂŠs (including avant-garde ones), no wasteful sound, no improviser ego-tripping.

Most of all, Evangelisti banished what he called âimprovising improvisation.â The idea of limitless freedom, he wrote, âsimply masks presumption and stupidity.â Improvisation had to be carefully prepared through extensive exercises in time, pitch, timbre, dynamics and collective listening. A player would provoke an action with a sound. It could be a squeak on a cello, a squawk on a trombone, a piano lid banged or some swooping electronic sound effect requiring a collective reaction within restraints of, say, the level of loudness. When someone violated the restraint, a new action was initiated.

Sounds were made, explored and worn out. The point was that a collective deep sonic dig transcending any individual composerâs ego leads to understanding and unleashing the potential power of the sound. The result, John Zorn has noted, was âsome of the strangest music ever made.â It was certainly, for all its discipline, some of the most intensely raucous. When I brought home the newly released âThe Private Sea of Dreams,â I almost got thrown out of my Haight-Ashbury apartment for playing it. Even hippies had their limits.

But performing in the Group was exactly what Morricone needed to grasp the effectiveness of unexpected sounds, be they instrumental, electronic or environmental â or a giddy combinations of all three â in even conventional film scores. The Group made you listen as you had never listened before, and Morricone used its syntax of sounds to get you to listen to film as you had never listened before. Everything in Morriconeâs effective film music that Times critic Justin Chang describes as counterintuitive comes from the hyper-intuition developed through the Groupâs listening process.

All this can be found within the West Coast DNA, which may hold another secret to why a Group-y Morricone could so perfectly suit Hollywood. The inspiration for the Group came from UC Davis, where Larry Austin, an experimental composer from Texas, had created the improvising New Music Ensemble in the early 1960s. Within days of Austin playing tapes of the ensemble for Evangelisti in Rome, they were making plans for the Group.

The Group went through various memberships and guest artists. Frederic Rzewski, who is the most important American composer-pianist of our time and who will be featured next week in our How to Listen series, was briefly a pianist in the ensemble, and it altered his approach to improvisation.

Morricone described to me how he ended the Group in 1980. A pianist suddenly began to play traditional concert music. Morricone yelled, âStop!â The pianist wouldnât, so the Group did. That was also the year Evangelisti died, and by then, Morricone had become in overwhelming demand as a film composer.

Ultimately, it was Morricone who turned increasingly traditional. As his fame grew, he spent his last glory days conducting successful concert tours, playing favorites from his hit film scores, which increasingly seemed to look backward rather than to the future. Even he seemed to lose interest in his large body of concert works, which, especially his four imaginative concertos, may well deserve revival. On the podium, he looked like he was going through the motions.

But at some point, a trumpet would do something really strange, the percussion would startle, there would be those fabulous Morricone silences. You can take Morricone out of the Group, but you canât take the Group out of Morricone. It was his secret sauce.

Ennio Morriconeâs collaborations with Sergio Leone, Brian De Palma, Quentin Tarantino and others made him one of the worldâs most acclaimed film composers.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.