Oscar-winning Italian composer Ennio Morricone dies at 91

- Share via

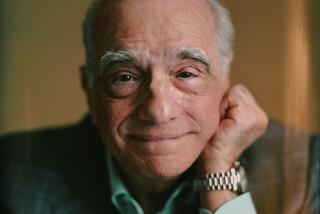

Oscar-winning film composer Ennio Morricone, who came to prominence with the Italian western “A Fistful of Dollars” and went on to write some of the most celebrated movie scores of all time, has died. He was 91.

Morricone’s longtime lawyer, Giorgio Assumma, told the Associated Press that the composer died early Monday in a Rome hospital of complications following a fall, in which he broke a leg.

A native of the Italian capital, Morricone composed music for more than 500 films and television shows in a career that spanned more than 50 years. At first he was closely associated with “A Fistful of Dollars” director Sergio Leone, for whom he scored six films, including “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” and “Once Upon a Time in America.” Established in his own right, Morricone turned out classic scores for films such as “Days of Heaven,” “Bugsy,” “Cinema Paradiso,” “The Untouchables,” “La Cage aux Folles” and “Battle of Algiers.”

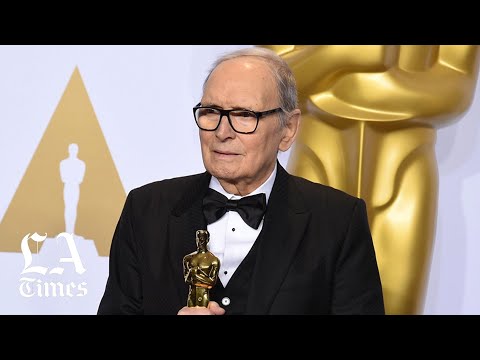

A favorite of critics, directors and other composers, Morricone’s score to the 1986 film “The Mission” was voted best film score of all time in a 2012 Variety poll. On his sixth nomination, he finally won a competitive Oscar, in 2016, for his score for Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight.” The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had awarded Morricone an honorary Oscar in 2007.

He also occasionally did live performances in which he conducted orchestra and choruses in both his film music and concert pieces he composed.

It was a 1960s recording made in Rome of the Woody Guthrie song “Pastures of Plenty” that launched Morricone’s international career. The seemingly incongruous mixture of sounds in the orchestration — surging violins, the crack of a whip, church bells, an electric guitar, an acoustic guitar, chimes and a chanting male chorus — so entranced Leone that he ditched his original choice of composer and hired Morricone to score what became 1964’s “A Fistful of Dollars.”

Morricone’s music, like the man who wrote it, was never shy.

“The best film music is music that you can hear,” he said in a 1995 BBC documentary about his life and work. “Music you can’t hear, no matter how good, is bad film music.”

Although Morricone scored several Hollywood movies, he usually did so from his home city of Rome and seldom traveled to Los Angeles. He never learned more than a handful of phrases in English and even refused an offer from a studio to buy him a house in L.A. His absence didn’t diminish his popularity among high-profile U.S. musicians — the 2007 tribute album “We All Love Ennio Morricone” featured performers as varied as opera soprano Renee Fleming, rocker Bruce Springsteen, cellist Yo-Yo Ma and the heavy metal band Metallica.

“He has taken so many risks, and his music is not polished whatsoever,” said Metallica lead singer James Hetfield in a New York Times interview. The band regularly used a theme from the western “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” in its concerts. “It’s very rude and blatant,” Hetfield said of Morricone’s music. “ All of a sudden a Mexican horn will come blasting through and just take over the melody. It’s just so raw, really raw, and it feels real, unpolished.”

Addressing the more melodic side of Morricone, film music composer and former rock musician Danny Elfman said in a 1999 Los Angeles Times interview, “Anyone who’s ever written any kind of romantic score has been influenced by him.”

If there is a common thread to Morricone’s work, it’s the mixing of that raw and romantic, expressed with a blend of unlikely instruments to create excitement, suspense, joy and pathos — sometimes all in the same film.

That was never more true than in “The Mission” (1986), set in 18th-century South America, in which a tune played on the oboe has a key role in the plot. In the movie, the oboe player is a Jesuit priest who is accepted, in part because of the music he makes, by a native tribe deep in the jungle. The score, which ranges from ominously dissonant to celebratorily tonal, features pan pipes and drums of various types to represent tribal sounds, plus an orchestra, chorus and child singers. As the action culminates near the end of the film, all these sounds can be heard fitting together like a puzzle that suddenly gets solved.

“These three elements: the oboe, the native music and Western music taught by the Jesuits had to be combined into a whole,” Morricone said in an English translation on the BBC program. “The union of these elements is very important. In them I see myself, spiritually and technically.”

Morricone was born Nov. 10, 1928, in a working-class neighborhood in Rome. His father, Mario, was a musician who played trumpet in night clubs and taught his son to play the instrument at an early age. Ennio did his first composing at age 6. “I wrote silly bits of music,” he said in a 1989 interview with British author Christopher Frayling. “They were hunting themes. I destroyed them.”

He enrolled at age 14 in the Santa Cecilia Conservatory, where he studied classical music, including works by contemporary composers. But at night he often subbed for his unwell father, playing trumpet in clubs. Graduating from the conservatory in 1954, he went on to compose several serious pieces. He married Maria Travia in 1956 and the following year they had a son.

“Little by little I realized that I couldn’t live on the very meager income from composing contemporary music,” Morricone told Frayling. He turned to arranging pop tunes and in just a few years became quite successful, working on songs for television variety shows and for famed stars such as Mario Lanza. The first film score for which he received a credit was for director Luciano Salce’s 1961 “Il Federale” (“The Fascist”).

Morricone soon found himself in demand as a film composer. Able to work fast, he picked up several more credits over the next couple years, including for two westerns. Those led to his being considered for the Leone film and when the two men met, Morricone had a surprise for the director. He told him they had met before, more than 30 years ago in third grade and Morricone had the picture to prove it. The class photo, from a school in Rome, showed the two boys sitting just one student apart from each other, although back then they were not close friends.

The recording of “Pastures of Plenty” sealed the deal for Morricone to write the music for “Fistful of Dollars,” and his unorthodox, upfront score for the film starring Clint Eastwood was credited with helping it become a worldwide success.

“I think the music of Ennio becomes almost visible, becomes almost a visual element in the film,” the late director Bernardo Bertolucci said in the BBC documentary.

Morricone and Leone teamed again for two more films in what came to be known as the “Dollars” trilogy of westerns starring Eastwood: “For a Few Dollars More” (1965) and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” (1966), which is likely the composer’s best known work.

In a 2007 tribute to Morricone, Los Angeles Times critic Mark Swed called it “audacious” music. “The whistle, the whoop, the ‘60s rock guitar, the ocarina, the quick-tongued trumpets, the simple harmonies, the catchy melody are a combination never before associated with the American West or anyplace or anything else,” Swed said.

The working relationship between the director and composer was so close that Leone sometimes had Morricone compose and record the music before the film was shot. Leone would play the music on the set to help set the mood for actors, and at times he would shoot the film to go with the music instead of the usual other way around.

In all, they did six films together, ending with “Once Upon a Time in America” (1984), which had one of Morricone’s most melodic scores. Leone died in 1989.

Among other directors whom Morricone worked with multiple times were Bertolucci, Federico Fellini, Brian De Palma and Roland Joffe.

After finishing the 1976 Bertolucci epic “1900,” Morricone cut back a bit on film and TV composing to spend more time writing orchestra works. He stopped working on U.S. films entirely, but for a different reason. “I was being paid no more than the worst American composers,” he said in the BBC documentary. “So I decided to stop working for the Americans.”

English producer David Puttnam broke that logjam by paying him what he wanted for the Warner Bros.-financed “The Mission.” “He doesn’t sell himself cheaply,” Puttnam said in the BBC documentary, “but he does give you everything.”

The one thing that Morricone did not get out of “The Mission” was an Oscar, though he was nominated. At the awards ceremony in 1987, the winner, instead, was Herbie Hancock for “’Round Midnight.”

Morricone did not hide his disappointment. “Despite all the prizes and awards throughout Europe, the thing not fulfilled is the Oscar,” he said in a 1999 Los Angeles Times interview. “I feel there is a hole in me. I just don’t understand it.”

That hole was partially filled in 2007, when the motion picture academy gave him an honorary Oscar for “his magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music.” Although the composer was visibly moved when he received the award from Eastwood, he could not help but remind the academy that it had passed him over for a competitive award.

In 2016, at age 87, he finally took home a competitive Oscar, for the score of “The Hateful Eight.” In his acceptance speech, he thanked the other nominated composers as a group but gave a special shout-out to John Williams, the “Star Wars” composer, a perennial academy favorite and fellow octogenarian who had been working nearly as long as he had.

In his later years, Morricone conducted highly popular performances of his works with large orchestras and choruses massed especially for the occasions.

Still, he kept on composing for film and television, with total credits surpassing 520. But taking a stance that was uncharacteristically modest, Morricone said his output was slight compared with at least one classical composer.

“If you think about it, Bach, for example, used to compose one cantata a week. He had to compose the music in time for it to be performed in church on Sunday,” Morricone said in a 2010 interview with the Quietus online arts site. “So if you just consider Bach, you will see that I’m practically unemployed.”

Morricone is survived by his wife, Maria Travia, whom he married in 1956, and their four children.

Colker is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.