Nine ideas for making our city’s public space more race equitable

- Share via

It was a photo that captured the divide. Late last month, Nick Swartsell, news editor at the Cincinnati alt weekly CityBeat, snapped an image of a group of young, white urbanites in the city’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood enjoying a round of beers in an alfresco dining space improvised along the street for the age of COVID-19. Just beyond the group was another sight: a flurry of masked marchers, fists raised, protesting the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The image, first published as part of CityBeat’s protest coverage, went viral after it was disseminated by television writer Ziwe Fumudoh on Twitter, where she wrote: “There are two Americas: one fights for Black lives and the other fights for brunch.”

It’s been retweeted more than 150,000 times and received almost half a million likes. (Though, to be clear, the photo was taken in the evening and not during brunch hour.)

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately claimed Black and Latino lives, and the uprisings, which have thrown into stark relief the way in which Blacks and Latinos die in disproportionate numbers at the hands of law enforcement, have forced a national debate about structural racism. (The BBC has a good roundup of charts that show the disparities between Black and white wealth accumulation, educational attainment, political representation, wages and employment.)

This same debate is roiling the world of design and urban planning, where conversations can often get tied up on issues such as bike lanes and height limits, without considering the larger inequities our cities perpetuate — such as the ways in which the public space is policed.

“Every week in America, people like Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd have their lives stolen because their visibility in public space goes against the ways we’ve come to understand who should have access to ‘outside,’” anthropologist and urban planner Destiny Thomas writes in an essay published recently by the website CityLab.

It was a point proved yet again when a young Black entrepreneur named Malachi J. Turner led a group of college students on a walking tour of a pair of upscale communities outside Sacramento last week. Several residents called law enforcement. Others took to Facebook to speculate that protesters had landed in the area, with one person stating: “Where are all my Second Amendment peeps at?”

Erin Kerrison, a scholar in the school of social welfare at UC Berkeley, noted in the Sacramento Bee how the default setting for public space is frequently white. “They imagine what is theirs, their streets, their grocery stores, their sidewalks, and what they claim is theirs against a Black threat.”

Prompted by the police killing of George Floyd, American culture has radically transformed in less than three weeks. Here are seven key shifts.

So how to build a city that is more equitable? One in which public space can be accessed by African Americans without threat or fear? The Times spoke with nine architects, planners and advocates for their ideas.

‘Stop killing Black people’

Tamika Butler is the director of planning for California at Toole Design, a North American planning and design company. Based in Los Angeles, she has worked on planning and equity initiatives for the city of Los Angeles.

Stop killing Black people. If we’re going to talk about how we are going to change public space, it’s stop killing Black people and stop criminalizing us.

I am a Black woman and I identify as a Black woman. (I always joke that if there’s a natural disaster, I’m going to find a Black woman because I know we will all be OK. We hold a lot on our shoulders.) But I’m also gender-nonconforming. I wear a suit and a tie and I have short hair. Many people see me as a Black man. So I understand the ways in which Black men are perceived in the system — and how women are erased.

My wife is white, and we’ve been pulled over in our car in downtown Los Angeles, leaving happy hour from her office. She’s a partner at a law firm. And she’s been pulled out of the car by police asking if she is with me by force — even if she says, “That’s my wife.”

The color of my skin scares people. And if Black scares you, it doesn’t matter what an architect or an urban planner does to design the city. If that officer has his foot on George Floyd’s neck, it doesn’t matter if there is a bike lane.

Reckon with history

Mabel O. Wilson is a graduate architecture professor at Columbia University and co-editor of “Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History From the Enlightenment to the Present,” published by the University of Pittsburgh Press last month.

Talking to architects, planners and architectural historians, many of whom are people of color, one of the things they say is that we need to recognize the entanglements of these fields in regimes of white supremacy. Until we do that work, we are just setting the scene for these events to happen again.

For example, we knew what redlining was, but now it’s back in other forms: gated communities, or the fact that there is no public housing but affordable housing that relies on private financing, or subprime mortgages pushed on people of color. You also have poisoned water in Flint [Mich.]. And you have a pandemic that has disproportionately affected people of color. It’s not just one thing, but a constellation — and it can be deadly.

The [design] field is 90% white in America. The built environment, it emerges from European encounters of colonialism. In the West, that’s what architecture is — the European project that reached out and developed a kind of system of domination economically, politically, racially. So architects need to understand that when you talk about racism or anti-Black racism, the cause is white supremacy. They have to reckon with this legacy.

Redress is needed

Rosten Woo is an L.A. artist who uses graphic design to render complex public policy issues in visual ways. He helped create the historical signs in Los Angeles State Historic Park and a mini-golf installation about zoning for the arts group the Los Angeles Poverty Department.

I think [planners] tend to have an ahistorical sense of how they move forward. Most planners can tell you a laundry list of injustices like redlining and disenfranchisement and freeways destroying neighborhoods. But people tend to compartmentalize that and say, “OK, we learned the lesson. When we move forward, we won’t do that again.” But you can’t just move forward. You have to reckon with it. We have built our environment on these super inequitable foundations.

One thing where that gets concrete is the park and open space piece. If you look at high-need neighborhoods versus low-need neighborhoods, it’s basically a map of whiteness. A tiny percent of the community parkland is in communities of color. The Los Angeles County average is about 3.3 acres per 1,000 people. But there are neighborhoods that have 52 acres and others that have 0.7.

It’s really extreme how inequitably those green spaces are distributed. So you can’t just be like, “How do we make parks wherever they happen to be more equitable?” The actual location of the parks is the bigger problem. It’s trying to think proactively of how you redress these inequities.

Explore temporary solutions

Faiza Moatasim is an assistant professor of urbanism and urban design at USC’s School of Architecture.

Oftentimes, when you are dealing with architecture and design professionals, there is this assumption that it’s a design problem. Well, it’s not bad design that is the cause of our unequal cities — cities are manifestations of our social values. Cities are unequal because our society is unequal.

Broadly speaking, how can we make cities more equitable? It’s finding ways to support the now. The big picture is important. In thinking about the unhoused population, you need housing — that’s important. But what can you do right now? In Los Angeles, for example, it’s illegal to sleep in a car but legal to sleep on a sidewalk. So how can we transform our cities in a proactive way so that people who are forced to sleep in cars have access to safe parking?

That forces us to rethink parking lots and parking structures — not just as a place to park, but as a place that someone might sleep. The biggest cost in those types of operations is security and bathroom facilities. And that is still pretty low when you compare it with building an actual building. But for the people who are forced into those situations, being able to sleep peacefully at night, with security, that is the No. 1 priority.

We are often scared of the temporary, that it will take away from the larger mission. But there is power in the temporary. You can do a lot with a lot less.

Reuse rather than rebuild

Christopher Hawthorne is the chief design officer for the city of Los Angeles and The Times’ former architecture critic.

One direct and positive step the city can take is to become a more thoughtful (and self-critical) client and patron when it comes to bringing emerging architects, particularly Black architects and architects of color, into the public-sector design process. We’re working on two initiatives right now — one with our Department of Building and Safety, the other with the Bureau of Engineering — to examine and update the range of ways that we hire and work with architecture firms.

Southern mayors and Virginia’s governor are striking while the iron is hot, using the unprecedented moment to get it done.

I’m also increasingly convinced that building equitable spaces means getting past the idea of always going for a brand-new, tabula rasa solution when we’re thinking about the future of a park or other open space. Instead, let’s redouble our commitment to taking care of, improving and re-imagining the spaces we’ve already built, with meaningful input from the people who use them every day. One of many things the Black Lives Matter protests should teach us about public space is that any street can operate as an effective plaza or gathering place if we want it to.

The right to be left alone

Leslie Kern is an urban geographer based in New Brunswick, Canada, who is the author of “Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World,” due out in July from Verso.

A lot of what we talk about when we talk about public space is the right to gather and the right to protest, a place where people should be able to have all of these social interactions. But from a gendered perspective, I think about the right to be left alone in public space. The ability to be left alone, to just be another person, that right is not often granted to women. People will speak to us, yell at us, harass us.

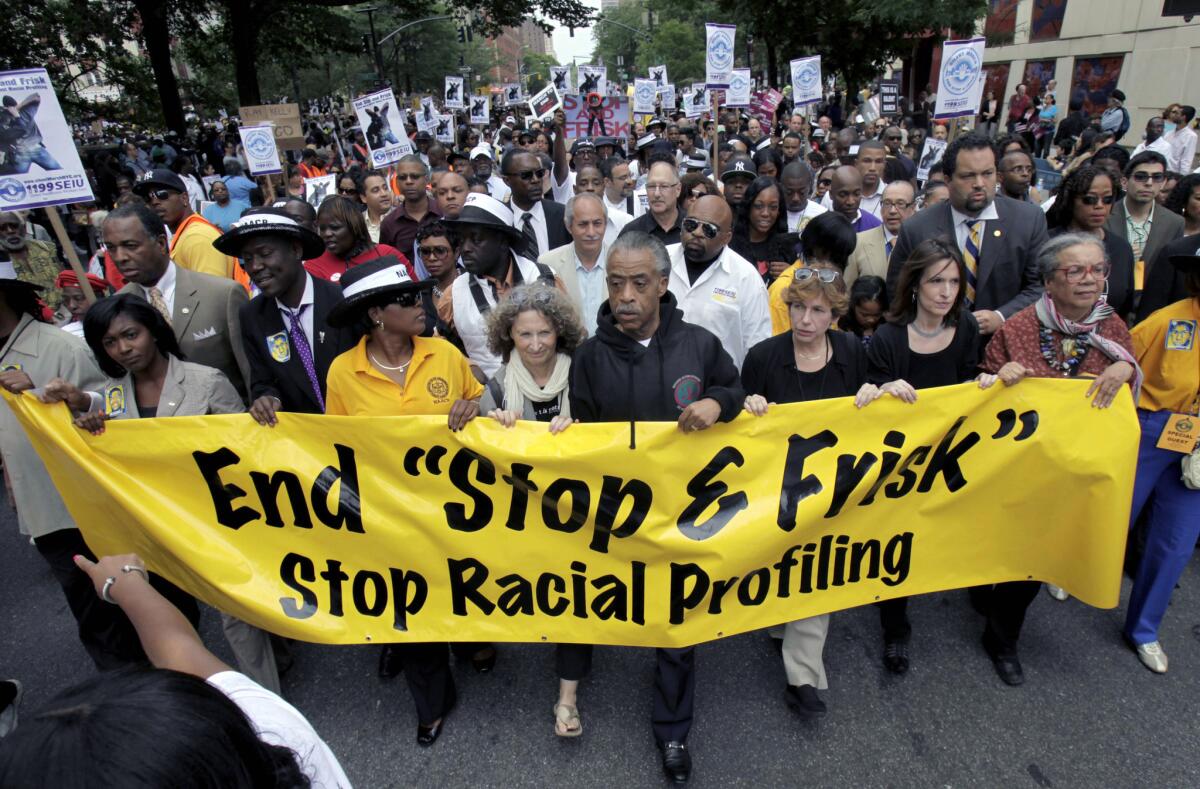

Expanding that to black people — think about Christian Cooper, who goes out to bird-watch and encounters a woman with a dog and has the threat of police violence leveraged against him. Or the story from a couple of years ago of the two men in a Starbucks arrested on suspicion of trespassing while waiting at a table for a business associate. Things like stop-and-frisk policing, where the police randomly stop you, it’s about surveillance of youth and people of color.

The creeping privatization of public space is part of the problem in terms of levels of surveillance, with private security that disproportionately affects poor people, homeless people, people of color. Anything that is viewed as a disorder becomes a target, and this view of disorder is shaped by race and class. So it raises the question of who are cities for? And whose presence are we questioning in one way or another?

Support community groups that exist

Adonia Lugo is an urban anthropologist based in Los Angeles and also the author of “Bicycle/Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance.” She helped found the transportation equity group People for Mobility Justice.

- Share via

Video of a bicycle demonstration in Leimert Park to protest the killing of George Floyd.

In L.A., there’s an emphasis on development as a way forward. The idea is if you build it, they will come. But adding rail infrastructure doesn’t necessarily increase ridership, and the people who rely on it get pushed out. There have been clear calls for removing police from Metro for quite some time, since there has been a lot of policing of behaviors. And across the country, there is a well-documented phenomenon of biking while Black. But it’s difficult to get urban planners and elected officials to see this as a problem of more than built systems.

There has been a lack of investment in developing robust organizations and programming in communities of color around sustainable transportation and being able to advocate for the type of transportation that makes sense. While there are some standout examples — like Ride On in Leimert Park and the East Side Riders Bicycle Club in Watts — people have had to have these total uphill battles to keep riding going.

What happens is that POC groups often have to figure out how to mold themselves to fit whatever funding is available, rather than the funding being crafted to support where this great community-rooted stuff has emerged.

Reinvent planning meetings

James Rojas, founder of the urban planning practice Place It!, is an independent planning consultant who leads workshops at the community level. Based in Los Angeles, he has worked in cities around the U.S., including Phoenix, Minneapolis and Portland, Ore.

You can’t talk about equity or race without talking about place. They are so intertwined. Planners often approach planning as engineers. It’s solving a problem. But it’s more about emotions. If you ask people what they need, they’ll say, “We need more parking.” But planning has no way of thinking of the fine-grain details. We need to plan for bodies, not just issues. What does our body need to make it feel healthy?

The format of planning meetings is wrong. Rather than producing a checklist, you let people articulate it with objects. If instead of “What do you want?,” you’re asked, “What is an ideal street?” You might be able to say, “I like a street with trees.” So in my sessions, I bring objects, and people work together to build a place that is built on memory of what makes them feel good. It’s about the details that make people happy: gardens and community centers and art museums. You get a different outcome that way.

Deep listening with community

Karen Mack is executive director of the community arts group LA Commons and a member of the L.A. City Planning Commission.

What I observe in public process is that there is not a great understanding of what it means to partner with community. It’s coming at this from the perspective of, “We have this toolkit of options and we want to check off the box that we engaged community.”

One of my favorite projects that we’ve done [with LA Commons] is a mural, “Heart of Hyde Park.” The mural is beautiful. [Painter] Moses Ball did a great job. But really it was about the process of creating the mural. We found leaders in the community who were invested in what we were doing — there’s a group called Hyde Park Organizational Partnernership for Empowerment, H.O.P.E., and they took on parts of the project. Moses is from L.A., but not from the neighborhood. They wanted someone local, so we made budget to hire a second artist.

We recruited youth, and they were able to gather stories that served as the basis of the mural. They were having these intergenerational dialogues — those connections are a fiber that creates strength in the neighborhood. And now one of the youth artists that worked on that project is running other projects.

It’s that deep community work. Deep listening. This made the public space more reflective of the people who live there. That’s equity.

COVID-19 has Thom Mayne, Michael Maltzan, Barbara Bestor, Rachel Allen and more Los Angeles architects rethinking design, from balconies to doorknobs.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.