How MacArthur Fellowship winner Walter Hood turns landscapes into sculpture

- Share via

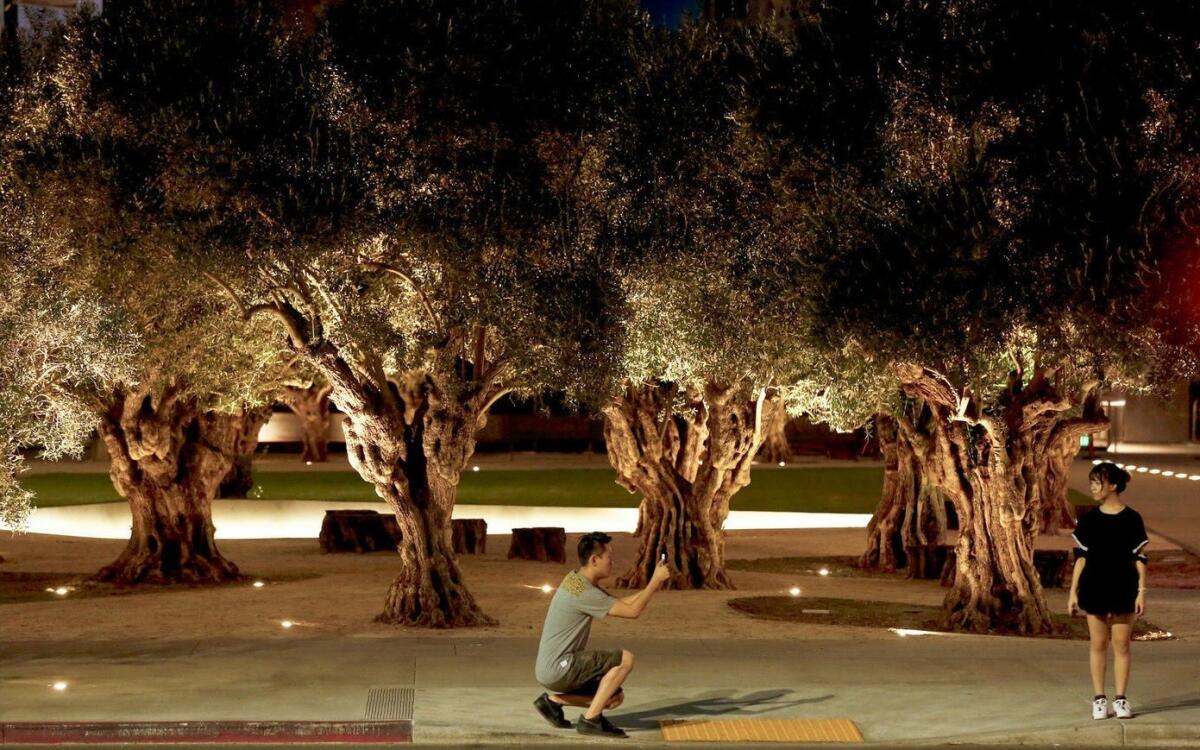

Visitors to the Broad museum in downtown Los Angeles have walked past those sculptural orbs of bushy green lawn busting through the sidewalk. Whimsical public art? Perhaps. But the work, designed by 2019 MacArthur Fellowship winner Walter Hood, is also a commentary on the Bunker Hill landscape.

“There’s a tunnel under there, on Grand Avenue,” Hood said. “So this idea of something bulbous makes you think about the ground underneath. It’s not solid. So in a way, this landscape is a fiction.”

Hood was among 26 fellows in the arts, science, law, social justice, education and other areas announced Wednesday morning by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The Oakland-based landscape and public artist was recognized for “creating ecologically sustainable urban spaces that resonate with and enrich the lives of current residents while also honoring communal histories,” the foundation said.

Only one of the 2019 fellows, historian and UCLA professor Kelly Lytle Hernández, is based in L.A. But Mel Chin, Jeffrey Gibson, Cameron Rowland and Hood are all artists who have recently exhibited work in L.A.

Chin, who is based in Egypt, N.C., participated in Los Angeles’ first public art biennial, the 2016 “Current: LA Water.” His land artwork, “The Tie That Binds: The Mirror of the Future,” was a native plant garden along the L.A. River in Glassell Park that addressed water conservation. Chin encouraged the public to copy him at “mirror sites” of their choosing.

Native American artist Gibson, based in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., addressed questions of racial identity and cultural belonging in the 2017 exhibition “In Such Times” at the Culver City gallery formerly named Roberts & Tilton, now Roberts Projects. His sculpture made from a wind turbine blade was at the Palm Springs Art Museum during the inaugural 2017 Desert X exhibition.

Rowland, who lives in Queens, N.Y., addressed the legacy of slavery and the slave economy, as well as questions of art and property, in his Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition “D37” this year. The exhibition juxtaposed found objects — a grandfather clock from a South Carolina plantation, used bicycles, discarded leaf blowers, even MOCA itself — and noted their origin stories in a booklet.

Hood, 61, defies easy categorization. He takes an architectural and fine arts approach to creating “ecologically and culturally sustainable” public spaces, he said, often transforming neglected urban areas for marginalized communities. He also designs public spaces for museums and other cultural institutions around the country. In both cases, he aims to illuminate the communal history of an area, turning his sites into “commemorative spaces.”

He is designing “ancestral gardens” for the International African American Museum in Charleston, S.C. The landscaping was inspired, in part, by the so-called “hush harbors” where African American slaves gathered, in secret, to practice religion and share West African traditions.

In 2002 Hood worked on L.A.’s Baldwin Hills Park Master Plan with landscape designer Mia Lehrer. His 2014 public sculpture “Coastlines” is a half mile of sandstone towers in a park at the Port of Los Angeles. He’s now designing a public artwork, “Saint Monica’s Tears,” for Metro’s Downtown Santa Monica Station.

That creative fluidity is representative of this year’s class, MacArthur Foundation managing director Cecilia Conrad said. The 2019 fellows are particularly hard to categorize, she said.

“Lynda Barry began as a graphic novelist and cartoonist but is also being recognized for her teaching methodology,” Conrad said. “Annie Dorsen is a theater person but one who’s relying on algorithmic theater and knowledge of computer science. And Walter is a landscape architect but he also thinks of himself as a sculptor. These people are hard to put in a box.”

Hood was in his office when he learned he’d been awarded the fellowship, which comes with a $625,000 no-strings-attached stipend to pursue new creative and intellectual projects.

“At first I thought it was a gag — really?!” he said. “I was floored. I walked around in a daze. I still am.”

How does Hood see urban spaces as public sculpture? All objects are pieces of sculpture, he said.

“So if you take light poles, a fire hydrant — someone designed these things,” he said. “They fill our urban environment, but in a way they disappear. So if you’re in a place that is economically poor, those are places that you can give life to things.”

Annie Dorsen, known for “Passing Strange,” has since focused on the intersection of theater and technology — and earned a MacArthur Fellowship for it.

He cited his firm’s 7th Street gateway project in Oakland as a good example. “We put seven faces of African American heroes over the road as a gateway, but we used the Caltrans signpost to do it,” he said.

“Jocko Goes to China” and “Jocko Goes to Los Angeles” are two porcelain sculptures of a lawn jockey, one created by a fabrication artist in Long Beach, the other by a fabrication artist in Jingdezhen, China.

“I collect racist memorabilia, everything from Aunt Jemima signs to lawn jockeys,” he said. “The idea — and I’m not the first artist to do it — is to take ownership of things that tend to marginalize. The lawn jockey is something that, growing up in the South, I always saw. So now, it’s being able to take it and manifest something that’s much more honest, much more beautiful about the actual piece itself.”

How might he spend the MacArthur stipend?

“This,” he said, “will just give me more freedom and the recognition to do what I’ve been doing — and more.”

2019 MacArthur Fellows

Elizabeth Anderson, philosopher

Sujatha Baliga, lawyer and restorative justice practitioner

Lynda Barry, graphic novelist, cartoonist and educator

Mel Chin, artist

Danielle Citron, legal scholar

Lisa Daugaard, criminal justice reformer

Annie Dorsen, theater artist

Andrea Dutton, geochemist and paleoclimatologist

Jeffrey Gibson, visual artist

Mary Halvorson, guitarist and composer

Saidiya Hartman, literary scholar and cultural historian

Walter Hood, landscape and public artist

Stacy Jupiter, marine scientist

Zachary Lippman, plant biologist

Valeria Luiselli, writer

Kelly Lytle Hernández, historian

Sarah Michelson, choreographer

Jeffrey Alan Miller, literary scholar

Jerry X. Mitrovica, theoretical geophysicist

Emmanuel Pratt, urban designer

Cameron Rowland, artist

Vanessa Ruta, neuroscientist

Joshua Tenenbaum, cognitive scientist

Jenny Tung, evolutionary anthropologist and geneticist

Ocean Vuong, poet and fiction writer

Emily Wilson, classicist and translator

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.